Cardiovascular disease in women

Cardiovascular disease in women is an integral area of research in the ongoing studies of women's health. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is an umbrella term for a wide range of diseases affecting the heart and blood vessels, including but not limited to, coronary artery disease, stroke, cardiomyopathy, myocardial infarctions, and aortic aneurysms.[3]

| Cardiovascular disease in women | |

|---|---|

| |

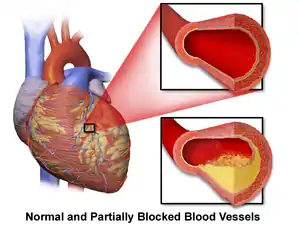

| Illustration of coronary artery disease comparing a healthy artery to an artery with atherosclerosis | |

| Specialty | Cardiology |

| Symptoms | Chest pain or feeling of crushing pain in the chest; Radiating pain in the arms or shoulder; Heartburn; Pain or discomfort in neck, jaw, upper back, or abdomen; Shortness of breath; Nausea/vomiting; Sudden and random sweating; Fatigue; Lightheadedness or dizziness |

| Risk factors | Traditional: Smoking; Obesity; Hypertension; Dyslipidemia; Diabetes Mellitus; Physical Activity; Ethnicity and Race; Socioeconomic status Unique: Age; Hypertensive disease of pregnancy; Gestational diabetes mellitus; Other pregnancy-associated conditions; Autoimmune diseases; Menopause; PCOS; Depression; Breast cancer treatment; Female sex hormones |

| Treatment | Electrocardiogram; Echocardiogram; Holter monitor; Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging; Exercise and nuclear stress tests; Cardiac catherization and angiogram; Cardiac computerized tomography |

| Frequency | 47.8 million (US, 2014)[1] |

| Deaths | 8.5 million (worldwide, 2015)[2] |

Since the mid-1980s, CVD has been the leading cause of death in women, despite being presumed to be a primarily male disease. Two types of CVDs are shown to be the leading causes of death in women globally according to the World Health Organization: ischemic heart disease and stroke.[4] However, until recently, the gender-specific data available on cardiovascular disease (CVD) has been sparse for numerous reasons. The risks of CVD were unaccounted for in women due to gender biases, under-representation in clinical trials, and lack of research.[5] These factors contributed to an increase in preventable deaths in women due to CVD.[6] Thus, this is now an integral area of research in the ongoing studies of women's health.

Overall, these factors are instrumental in the key differences seen in CVD presentation, which must be accounted for in diagnostic and treatment practices from healthcare providers.

Diagnostic gap

Cardiovascular disease in women may be misdiagnosed or underdiagnosed in women for a number of reasons. CVD, especially heart attacks, often presents symptoms in women differently than in men due to anatomical and hormonal differences.[7] Research has shown that women may present with symptoms that are classically associated with heart attacks, such as chest pain and shortness of breath, but also with atypical symptoms such as neck, jaw, arm, or shoulder discomfort, nausea or vomiting, heartburn or indigestion, fatigue, headaches, and palpitations.[8] Some healthcare providers may misidentify the causes of these symptoms, attributing them to gastrointestinal or psychological causes instead.

Moreover, although certain factors traditionally associated with developing CVD include age, hypertension, smoking, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia and are similarly influential on women as on men, recent research has found additional risks that should be added to this list as non-traditional or emerging factors. These include pregnancy-associated disorders such as preeclampsia and gestational diabetes, polycystic ovary syndrome, and even depression. This discrepancy is furthered by the under-enrollment of women in research studies establishing a CVD treatment baseline in women for healthcare practitioners.[9]

Furthermore, the anatomical features of the cardiovascular system have some differences in size between men and women. The size of the vessels in women is generally smaller in comparison to men. Thus, a smaller blockage can cause as much damage to women as a regular-sized blockage in men.[10] Women also have a smaller ventricle size than men. This lowers the volume pumped out of the ventricle to the rest of the body, thus requiring their heart to beat faster to ensure a similar amount of blood is pumped out as men.[10] These differences in addition to the cardiovascular functional differences, i.e. a slower fight or flight response, sympathetic activity, and a high rest and digest response, parasympathetic activity, may result in differing presentations of women's illnesses.[11]

Shifts and trends

According to a survey conducted by the AHA in 2000, women are now more aware of CVD as the leading cause of death in women than in 1997.[12] Close to 90% of women are now aware that women experience heart disease symptoms gradually in later years and that the initial hours of treatment are critical to reducing damage to the brain and heart. This is further supported by a study done in Italy in 2022 that found a vast majority of their participants were able to successfully identify CVD as a leading cause of death in women.[13]

However, many women are still unaware of the impact of CVD on women's health. This may be due to infrequent exposure to the concerns and a deficit of personalization in education to these groups, and little involvement of women in CVD research until 1986.[14] Numerous studies have noted that many women were unable to identify common risk factors or acknowledge whether they were at possible risk of developing CVD, with quite a few even believing that CVD was a male-exclusive condition.[13]

This lack of awareness seems to also be prominent in the age groups of 25 to 34 years. Nearly 72% of women in this age group consider cancer to be the leading cause of death; however, as age increases, the understanding of heart diseases has also been shown to increase. A national survey conducted by AHA in 2012, suggested increased rates of awareness and consciousness. According to the fifteen-year trend report, some of the significant changes are as follows:[15]

- In 2012 the level of awareness increased in women from different ethnicities with percentages rising up to 65% white, 36% black, and 34% Hispanic.

- In terms of knowledge of the symptoms of heart attack, 18% of women responded with nausea, while 56% responded with chest pain.

- In case of experiencing a heart attack, 10% of Hispanic women were reported to initially take aspirin, compared to 22% black and 18% of white women.

- The top 3 health management issues were reported to be exercise (by 49% of women), weight (by 47%), and cholesterol (by 45%).

- Analysis of data suggests further improvement in the educational efforts and awareness among women, especially of racial and ethnic minorities, as they face higher mortality rates.

As a follow up, a recent 2019 AHA survey of the awareness of CVD being the leading cause of death in women has been on the decline in the last decade.[16] The greatest differences were seen among Hispanic women, non-Hispanic Black women and the age group of 25 to 34 year old.[16] These trends are similar to those ones found in the 2012 survey done by the American Heart Association. This shift in knowledge demonstrates a great need for cardiovascular health programs targeted to women, to ensure that they are able to successfully access the needed resources to ensure successful CVD treatment and prevention.

Moreover, trends have also demonstrated a difference in CVD risk and treatment amongst women from different ethnicities. In the 1980s, African American women had double the mortality rates compared to other women between the ages 30 to 39.[17] Although this number has improved, in comparison to white women, the disparity still persists.[18] A 2007 study that black and Hispanic women were nearly half as aware (31% and 29% respectively) than their white counterparts (68%).[18] This is alarming as minority groups have been shown to be at an increased risk of higher cholesterol levels and many other risk factors that cause CVD.[19][20] Studies have found this may be due to lack of educational intervention being targeted to these groups to ensure equity access to health resources.[21]

Future research is working to establish gender-specific guidelines and ensure that treatments, diagnoses, and overall practices are adjusted to encompass the differences of women with CVD into clinical application.

Cardiovascular Disease Diagnoses

CVD is an umbrella term to encompass numerous conditions of the cardiovascular system. These can be chronic, i.e. ongoing issues, or acute, i.e. having a sudden onset. There are several different types of CVD, of which the most prevalent are:

Arrhythmia

Arrhythmia (also known as cardiac arrhythmias, heart arrhythmias, or dysrhythmias) is an irregular heartbeat. The heartbeat is the rate at which the heart beats: too slow (bradycardia) or fast (tachycardia).[22] Although it is normal for the heartbeat to fluctuate at times of activity or rest, chronic consistent irregularity may cause not enough blood to reach all parts of the body, as well as put the individual at an increased risk of blood clotting.[23] This can lead to other forms of CVD that may be life-threatening, such as a stroke, if the blood clot travels to the brain. As women typically have more rapid normal heart rates and receive differing electrocardiogram results than men, is important for practitioners to approach these cases differently than men to make a rapid diagnosis.[24]

Coronary artery disease

Coronary Artery Disease (also known as coronary heart disease or ischemic heart disease) is a result of the build-up of substances in the walls of the vessels that provide blood to the heart and parts of the body, the coronary arteries.[25] These substances, which can include cholesterol, cause the vessels to narrow, preventing blood from flowing smoothly through.[26] As the heart compensates for this decrease in blood going out by pumping harder, this can lead to muscle weakness over time, subsequently leading to other life-threatening forms of CVD. The unusual symptoms seen in women with this condition include a sensation of crushing pressure and fatigue – feeling low on energy.[27]

Congestive heart failure

Congestive heart failure (CHF) is where the heart muscle is unable to pump blood efficiently or at its normal capacity, preventing it from meeting our body's needs.[28][29] This can cause fluid build-up in various organs, including the lungs and the heart itself, which also makes it life-threatening.[30] Women and men tend to present similarly for CHF, although women frequently report having more of the symptoms, such as shortness of breath.[31] As well, women typically reflect a normal level of amount of blood pumped from the heart, known as the ejection fraction, which makes diagnosis difficult as it is a crucial sign used to identify CHF.[31]

Myocardial infarction

Heart attack/Myocardial infarction is when the blood flow to parts of the heart is blocked, due to various reasons including plaque build-up, this can cause the heart muscle to die from not being used.[32] This can lead to permanent heart damage, and may even result in death if not treated efficiently. Women can present with different symptoms than men, including jaw pain and nausea/vomiting, thus it is important to be alert for unusual symptoms reported by women.

Peripheral arterial disease

Peripheral arterial disease: narrowing of the arteries that provide blood to the extremities due to the build-up of plaque.[33] The lack of oxygen and nutrients can lead to tissue death and subsequent loss of the effected extremities.[34] For this disease, women may or may not show signs, i.e. presenting asymptomatically, which can be a challenge in diagnosing.[34]

Stroke

Stroke is a result of limiting or blocking the blood supply to a part of the brain, preventing the tissues from receiving the needed oxygen and nutrients to continue to work.[35] This blockage can occur through a blood clot cutting off circulation through an artery – an ischemic stroke –, a blood vessel bursting – a hemorrhagic stroke –, or blood flow is impaired for a certain amount of time – transient ischemic attack.[35] Similar to other forms of CVD, symptoms unique to women include nausea/vomiting, shortness of breath, or even seizures.[36]

Valvular Heart Disease

Valvular heart disease is any CVD that is caused by the valves, the door between the chambers of the heart; aortic, mitral, tricuspid, or pulmonary valve.[37] These can be seen as either valve narrowing, also known as or stenosis, or regurgitation, incomplete closing of the valves which leads to leaking of blood backward through the chambers of the heart.[38] Of these, mitral regurgitation followed by aortic stenosis are the most common forms found in women.[39]

Symptoms

CVD is the leading cause of death in women worldwide.[4] Studies have shown a recent successful decline in CVD mortality overall. However, there is a strong indication for male-specific reductions being implemented in practice, thus female mortality still remains high, despite the incidence of CVD being lower.[40][41] The number of women surviving and dying from CVD far outweighs the number of men in comparison.[42]

Due to anatomical and biological differences, women with CVD have been shown to present with the expected symptoms, as well as unusual and not expected symptoms of CVD in comparison to men. The traditional, or common, symptoms seen in both men and women include:

- Chest pain or feeling of crushing pain in the chest

- Radiating pain in the arms or shoulder

- Heartburn

However, some studies have shown that chest pain is not as common a symptom in women.[43] Thus, its absence cannot rule out the likeliness of CVD.

For the atypical symptoms, there are numerous that are commonly vague and seem to be unattached to specific diagnoses. Women generally develop angina and are less likely to present with myocardial infarction at the onset of cardiovascular diseases. The other symptoms to account for include:

- Pain or discomfort in neck, jaw, upper back, or abdomen

- Shortness of breath

- Nausea/vomiting

- Sudden and random sweating

- Fatigue

- Lightheadedness or dizziness[44]

Overall, these symptoms seem to be more present at rest than any other time of day for women, and at times of emotional distress. Women also tend to report milder symptoms, while also experiencing a combination of more symptoms than men.[31][44]

To ensure that practitioners are able to catch all cases and forms presented to them, it is crucial to ensure that women's diagnostic tests are adjusted to include all of these symptoms appropriately.

Causes

As there are a variety of CVDs and causes for CVD, there is no one specific mechanism that can cause CVD. However, there are general components shown to promote CVD development which can be found in a few pathways.

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS): ROS are produced through numerous processes in our cells, including the induction of oxidative enzymes. The notable species involved in human cells include superoxide anion (O2−), hydroxyl radicals (OH), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2).[45] Not only does ROS physiologically have a role in controlling the vasculature through tone and endothelial and cardiac function, but it also is a vital player in inflammation, promoting apoptosis, angiogenesis and much more.[46] Additionally, ROS causes oxidative stress within the body which, although may not be the sole proprietor, exacerbates the various factors that contribute to developing CVD, especially hypertension.[47] Finally, ROS also act as signaling molecules to induce the body's inflammatory response to prevent any further damage from happening, which can lead to cell and tissue damage of the vasculature if not moderated appropriately.[48]

Induction of oxidative enzymes: Cytosolic oxidases are another critical component in ROS production. These enzymes transfer electrons to create radicals or superoxide, and increase oxidative stress.[49] These enzymes have also shown to be present in various physiological stressful situations, which is associated with hypertension and other traditional risk factors negatively impacting CVD.[45]

- Xanthine oxidase (XO): XO, under normal circumstances, is an important enzyme in producing uric acid, released from the kidneys.[50] These are typically located in the liver, however under times of stress from ROS, can increase its activity.[50] This elevates vascular tone and even ROS production in the form of superoxide, thus contributing to higher oxidative stress.[50]

- Nitric oxide synthase: Nitric oxide synthases are known for producing nitric oxide, which has numerous functions in the body including vasodilation – i.e. widening of the vessels.[45] Nitric oxide reacts with other forms of ROS to create potent oxidants, consequently causing other pathologic conditions, including heart failure and myocardial infarction.[45] Moreover, this family of enzymes are crucial signaling molecules in regulating vascular tone and multiple other functions.[51] Thus, any disruption in regular functioning impacts the vascular tone regulation.

- NADH/NADPH oxidase: These enzymes contribute significantly to the amount of ROS present in the body.[52] If in cardiac distress, an individual may induce excessive production, which may in turn lead to the pathogenesis of varying forms of tissue damage and cellular dysfunction in cardiac muscles.[45]

Uncoupling of Mitochondrial electron transport chain: The mitochondria is a contributor to the levels of ROS we see within our body. Not only does it produce it, but is also vulnerable to the damage caused by ROS. It also is a key player of cell function in the cardiovascular system.[53] With this damage to the mitochondria, the cell's function may be altered as not enough energy is being produced as needed, thus hindering the cell's ability to function optimally.[54] These events create a disastrous feedback loop where further mitochondrial damage results in increased ROS production, which furthers the damage and contributes to the risk of developing CVD.[54]

Immune cell infiltration and cytokines: A large contributing risk factor to the development of CVD is the production of plaque, also known as atherogenesis or atherosclerosis. This condition is known to involve multiple inflammatory cascades from the immune system responding to varying pathogens.[55] Elevated inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-⍺, initiate a cascade conducive to plaque production.[56]

Risk factors

There are numerous risk factors that have been found to be associated with developing CVD. A number of them are considered traditional, as they are found in men and women with CVD at high rates. However, there are also unique risk factors found only in women that are commonly associated with this group developing CVD. The following list includes the predominant ones found in many cases of CVD in women.

Smoking

Smoking has been well established as risk factor for plaque formation which can lead to developing different forms of CVD.[57] Previous studies have shown that 4-5 cigarettes per day almost doubled the risk of CVD and 20 cigarettes per day increased the risk of CVD by 6 times.[58] Women who smoke face up to a 25% increased risk of developing CAD compared to their male counterparts, with studies showing that reduction in smoking decreased the incidence of CAD in women by 13%.[59] Furthermore, second-hand smoking may increase the risk of CVD by 25%.[60]

Obesity

Obesity has been shown to be associated with several other factors that can cause CVD, such as dyslipidemias. With increasing body mass, the risk of developing various CVDs, such as ischemic stroke and coronary artery disease grows as the unhealthy lifestyle maintained prevents the cardiovascular system from functioning optimally.[61] Women make up about 40% of obese adults over the age of 20. Postmenopausal women are also more likely to experience fat redistribution to the abdomen and develop metabolic syndrome, resulting in increased susceptibility to obesity.[59]

Hypertension

Chronic high blood pressure (hypertension) alters the structure of vessels overtime, such as narrowing or complete blockage of blood flow through.[61] This can subsequently lead to CVDs, including stroke. The prevalence of certain disorders such as fibromuscular dysplasia is increased in premenopausal women and can lead to secondary hypertension.[62] These factors, including others such as preeclampsia, have been shown to contribute to the risk of developing hypertension, and thus, consequently, CVDs from the resulting damage.[63]

Lipids

Cholesterol, is a type of lipid that has diverse function in the body. There are several types of cholesterol but the main two are high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL). Then levels of these cholesterols can be determined by a blood test. HDL cholesterol is known as "the good cholesterol" and ideally it is recommended to have a high level of this cholesterol. HDL cholesterol works by removing LDL from the blood stream and returning it back to liver where it can not cause cardiovascular damage.[64]

LDL cholesterol is known as "the bad cholesterol" and it is recommended to have a low level (130 mg/dL or less) anything higher can lead to a higher CVD risk. When there is a high level of LDL cholesterol in the blood it is up-taken by inflammatory cells known as macrophages. The high burden of LDL cholesterol inside macrophages leads to an inflammatory response, which ultimately damages the inner lining of the blood vessels. Due to this damage, macrophages invade the cell wall of the blood vessels and cause the formation of a plaque. A plaque can lead to obstruction of the blood vessel and if this were to occur in a coronary artery it could increase the risk of a myocardial infarction (heart attack).[65]

Diabetes mellitus

The high blood sugar levels associated with diabetes mellitus is also an important cardiovascular risk factor to consider. Data suggests that women with diabetes are at five times greater risk than those without for developing CVD.[66] Uncontrolled levels of glucose can cause damage to the vessels and nerves alike, increasing the risk of developing other conditions, including CVD.[66] Women with type I diabetes were found to be twice as likely to experience adverse cardiovascular events when compared to men with the same disease, but were less likely to receive aggressive treatment to control modifiable risk factors.[59] Women with Type II diabetes are also at greater risk than men with the same condition despite similar glycemic control.[67]

Gestational diabetes mellitus

Similar to hypertensive disease of pregnancy, the already prevalent risk factor of diabetes mellitus combined with pregnancy puts women at increased risk of developing CVD. Women diagnosed with gestational diabetes are at a higher risk of developing traditional risk factors for CVD, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hypertension.[62] The irreversible changes made during pregnancy may make these women prone to CVDs in the long term. Additionally, women diagnosed with gestational diabetes remain at higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus and CVD, despite blood sugar metabolism returning to normal post-pregnancy.[59]

Preeclampsia

Hypertension can be severely damaging to vessels and the heart and cause CVD to develop. Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy such as pre-eclampsia can be seen in 10% of pregnancies and has been recognized as a risk factor for developing new-onset hypertension after pregnancy.[59]

Other pregnancy-associated conditions

Pregnancy offers numerous vascular and metabolic changes that, although may seem temporary, result in long-term effects on the cardiovascular system. Women who deliver prior to 37 weeks gestation are at increased risk of developing CVD, with additional risk depending on the number and timing of preterm births.[68] Data suggests that women with a history of preterm births have two times the risk of CVD-related deaths than women with regular-term births.[69] This may be due to the complications associated with preterm birth and its effect on the mothers. Additionally, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), which affect up to 10% of all births, in prior pregnancies is associated with an increase in maternal CVD risk for both the mother and the baby.[70] Finally, prior pregnancy loss, including miscarriage and stillbirth, also contributed to a two-fold increase in risk of maternal CVD.[62]

Menopause

Estrogen has several cardioprotective effects on women, thus during the age of fertility – i.e. puberty to menopause – females are at a lower risk of developing CVD. However, menopause is associated with a decrease in estrogen production. This allows for typical cardiovascular issues to implement their effects with little protection from the women's body. In rare cases, early menopause is correlated with increased CVD risk, although the relationship between the two is complex.[62] Premature menopause is defined as menopause prior to the age of 40. Although the relationship between the two is complex, it seems to be due to the prevalence of atherosclerosis in perimenopause.[71]

Physical activity

Lower levels of fitness are commonly associated with blockages and obstructed blood flow found in CVDs.[72] As exercise promotes the use of the heart and improves oxygen affinity for muscles, this can help relieve stress from the heart and allow for it to pump at a normal pace while providing more nutrients and oxygen to the body.[73] An observational study found that those with limited physical activity in their day were at a 4.7 times increased risk for stroke and other forms of CVD.[74]

Ethnicity and race

The prevalence of CVD has been shown to vary greatly amongst different ethnic and racial groups. Overall, ethnic minority women exhibit greater risk factors for CVD than white women.[75] Black women are at the highest rate of CVD-related death.[76] The cause for these gaps is still unclear, however, this may be related to genetics, socioeconomic status, education status, or inequitable health resources access.[75]

Socioeconomic status

Lower socioeconomic status has been shown to be largely associated with an increased risk of CVD development.[77] This may be due to a combination of psychosocial risk factors affecting those in these groups. Additionally, inequitable access to much-needed resources to appropriately identify and treat these conditions may lead to delayed diagnosis and inability to treat appropriately.

Age

The risk of CVD development increases as women age. During the fertility age of a woman, the high levels of estrogen provide cardioprotective effects.[41] This, however, curbs significantly after menopause and increases the prevalence of CVD found in women.[78] Research has found that for women 75 years old and higher, the incidence of CVD is significantly higher than for men.[41]

Autoimmune diseases

Certain autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) are significantly more likely to occur in women.[43] Some populations of women are also more likely to be affected than others. For example, SLE is two to four times more prevalent in black women when compared to white women.[62] Studies have also shown that women with SLE are at least nine times more likely to experience a myocardial infarction when compared to the general population, with some estimates showing a 50-fold increase in risk. Similarly, RA increases the risk of death from CVD by 50%.[59][62] In autoimmune diseases, the immune system reacts to the individual's antigens itself, which can cause local or systemic issues.[43] This is furthered by the microvasculature in women that puts women at increased risk to develop autoimmune diseases themselves.[43]

Polycystic ovary syndrome

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is an endocrine disorder prevalent in young women that is classically associated with irregular menstruation, androgen excess, and infertility. It is unclear whether PCOS is associated with an increased risk of developing CVD. However, PCOS is associated with multiple traditional risk factors of CVD such as diabetes, obesity, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, which may naturally put the individual at increased risk of developing CVD.[62]

Depression

Due to biological and sociological causes, women are twice as likely to have depression when compared to men.[79] Studies have shown that women with depression are at greater risk of developing CVD when compared to peers without depression, although this relationship is still unclear. Moreover, depression has also been associated with smoking, a traditional risk factor for CVD.[59]

Breast cancer treatment

Because of the location of the heart in relation to the breasts, breast cancer treatments have shown to cause the increased risk, acute or chronic, of CVD.[43] Exposure to radiation and chemotherapy in cancer treatments have shown to cause complications in the heart and its blood vessels, causing scarring or stiffening of heart tissue, which is detrimental to the heart's function.[80]

Hormones

Estrogen and other associated female sex hormones have been shown to have major cardioprotective effects on women.[72] This may be why it is less common to see women with CVD prior to menopause, after which estrogen levels decline rapidly. This causal relationship is still yet to be established clearly, as unfortunately hormone replacement therapies have not been successful in controlling this effect and may reflect a larger feedback loop in play to protect females of reproductive age from CVD.[76]

Diagnostic Tests

There are various tests that are used to diagnose CVDs. These include scans, imaging, blood work, and other laboratory tests. Here are the most frequently used diagnostic tests:

- Electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG): An ECG OR EKG monitors the wave representing the activity of the heart.[81] Any discrepancies or changes in the typical patterns indicate a cardiac condition, such as CVD, affecting the individual.

- Echocardiogram An echo provides an outline of the heart's function to help assess how well it is operating.[82] This is often combined with a Doppler ultrasound to help track the blood flowing through the heart's chambers and valves.

- Holter monitor: The Holter monitor is a portable device worn for a few days to monitor the heart's rhythm and any changes seen throughout the day.[83] This allows for a more in depth understanding of how well the heart is functioning and whether any irregular patterns are common or infrequent.

- Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): A cardiac MRI is an imaging machine that uses waves to develop a clear picture of your cardiovascular.[84] It allows for a 3D image of the heart to be produced to allow for more thorough investigations of any issues.

- Exercise stress test: This is a physical activity test for healthcare providers to be able to see how an individual's heart functions in times of physical stress.[85] The results from this test can demonstrate how to guide treatments for different conditions and even the efficacy of the current treatment in affected individuals.

- Nuclear stress test: A nuclear stress test involves trace amount of a radioactive substance put into your blood and is followed as it flows through the heart.[86] The imaging machine uses this as a guide to create a picture of the heart and the flow.[86] By following the flow of the substance, healthcare providers are able to better understand where the impairment is and in what form.

- Cardiac catheterization and angiogram: In this procedure, a thin tube is inserted and threaded to the chambers of the heart. This catheter allows for varying instruments to be inserted through it to either measure blood pressure, collect blood samples, or to remove a sample of the heart's tissue for further testing.[87]

- Cardiac computerized tomography (CT) scan: This cardiac CT scan is an x ray imaging machine that shows the blood supply to the heart and its arteries. This form of testing offers a non-invasive method to assess for narrowed or blocked vessels.

Treatment and Prevention

As CVD is the primary result of long-term damage to the cardiovascular system, research has been unable to develop a way to cure it permanently. However, through the available therapies and prevention strategies, there are methods of bettering its effects and making it so the individual's quality of life remains. This can help manage and reduce further risk of developing life-threatening CVDs. The strategies that have been established in routine care include pharmacological therapies, lifestyle changes (including nutrition and exercise), surgery, and smoking cessation.

Pharmacological therapy: Various medications have shown to mediate the negative symptoms of CVD. These typically work to lower the individual's blood pressure or widen their

- Angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB) & Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI): Both types of drugs work to limit the effects of angiotensin II, which raises blood pressure through a feedback loop in the kidneys.[88] They have shown to greatly reduce the mortality associated with CVDs, with ACEIs being more effective than ARBs.[89]

- Aspirin: Aspirin, or ASA, promotes platelet function inhibition which reduces the risk of plaque buildup in vessels.[90] This has been shown to alleviate the effects of vessel narrowing and blood flow impairment, and prevent numerous CVDs. The Women's Health Study in 2005 also found that Aspirin reduced the risk of developing stroke, as well as myocardial infarction in some age groups, in the long term.[91]

- Beta-blockers: Beta-blockers impede the effects of adrenaline, also known as epinephrine, and subsequently slow the heart rate.[92] This type of medication is generally prescribed for hypertension, a major risk factor for many CVDs. However, recent studies have shown that this medication may lead to a higher rate of heart failure than men, thus these medications should be taken with precaution.[93]

- Blood thinners: Blood thinners prevent clot formation, which contribute to vessel blockage, and is an effective method of anticoagulation that naturally plays an important role in cardiovascular system conditions.[94] Low dose blood thinners have shown to significantly reduce the risk of developing stroke, heart attacks and even the mortality associated with CVD.[95]

- Calcium channel blockers: Calcium channel blockers are vasodilators, i.e. widen our arteries by regulating the calcium entering the cells, which lowers blood pressure. This has shown to be effective across all patient groups regardless of age and severity.[96] This has been shown to be even more effective in combination with other therapies and must be used in moderation to prevent chronic cell damage.[97]

- Diuretics: Diuretics assist the kidneys in clearing extra fluid present in the body to help maintain a steady blood volume for the heart to pump around.[98] This helps bring blood pressure down, relieving pressure on the vessels and, consequently, the heart, thus making it a successful treatment for hypertension.[99]

- Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT): HRT is taken by women to replace the declining estrogen levels during times of menopause.[100] This is to control the cardio-protection offered by estrogen as women hit menopause and their levels decline.[101]

- Nitroglycerin and Other Nitrogen Oxides: Nitroglycerin and other nitrogen oxide use have been a strong influence on vasodilation, cell permeability, inflammation, and various other cardiovascular processes.[102]

- Statin therapy: This form of therapy aims to reduce levels of fat in the blood, specifically triglycerides and cholesterols.[103] The proposed mechanisms for them are that they stabilize the plaque and reduce blood clots, which prevents most CVDs from developing. As a primary prevention, they are significantly effective on patients at reducing the mortality and other life-threatening aspects of CVD.[104]

Nutrition and exercise: Adjusting an individual's lifestyle through their diet choices and increased physical activity has shown to reduce the long-term negatives associated with most risk factors, including plaque buildup and weakening of the heart muscle. Exercise has been shown to strengthen the heart muscle, allowing it to pump greater blood volume at a regular pace, thus preventing overexertion and tissue damage.[105] Additionally, a diet with low trans fat, saturated fat, refined carbohydrates, and sugar-sweetened beverages, and enriched with fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and unsaturated fats have reflected a significant reduction in the risk of developing.[106]

Smoking cessation: The adverse effects associated with smoking have overwhelmingly shown it to contribute to numerous risk factors that cause CVDs. These include contributing to atherosclerosis and contributing to blood clot formation.[107] For patients that have a history of smoking, it is important to focus on quitting smoking to prevent additional damage and allow healing to begin.

Surgery: In severe cases of CVD, various forms of surgeries offer a more permanent treatment to replace or remake the affected vasculature to prevent this from reoccurring.[108]

- Coronary angioplasty: the insertion of a thin tube with a balloon on the end into the clogged artery which becomes inflated to widen the channel for blood to pass through. In some cases, a stent is left behind to maintain the opening and prevent further relapse of the artery.[109]

- Coronary artery bypass graft: using another blood vessel to replace and divert blood around an occluded vessel to maintain regular blood flow of nutrients and oxygen, and prevent tissue death.[110]

- Heart transplant: the replacement of an individual's heart that is affected by disease with one of a healthy donor.[111]

Depending on the risks associated based on age, type of disease, prognosis, pregnancy or menopausal stages, the following primary preventions can be prescribed to women under the guidance and proper consultation with their healthcare provider.[59][62]

Epidemiology

CVD remains the most common cause of death for women, with approximately one-third of deaths worldwide attributed to CVD.[112] In 2015, approximately 8.5 million women died from the disease.[113]

In the United States, approximately 47.8 million women over the age of 20 were diagnosed with CVD between 2011 and 2014, and data from 2015 shows over 400,000 deaths due to CVD in women.[1] While overall deaths from CVD are falling, the decline is slower in women, particular black women.[114] The death rate for women with CVD surpasses that of men from CVD.[115] In Europe, over half of the deaths in women are attributed to CVD.[116] The death rate in some Eastern European countries is high, with over 500 deaths per 100,000 population attributed to CVD. Studies predict that in certain developing countries in Asia and Africa, women will account for a greater percentage of deaths related to CVD by 2040.[117]

Cardiovascular disease is more prevalent in older populations. On average, women develop CVD approximately 10 years after their male counterparts.[115] In the United States, approximately 6% of women over 20 have coronary heart disease.[118] The highest prevalence of CVD is present in adults over the age of 80, and women and men have similar rates of disease after the age of 60.[1]

History

In the last few decades, the greatest changes have been made to acknowledge and focus on sex as an influential factor, thus establishing a great need to incorporate women into research. The events of significance are as follows:

- In 1994, the United Nations stated that in order to establish a policy, there must be more sex-specific research done regarding treatment efficacy, thus encouraging researchers to pursue this line of inquiry.[119]

- The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of the United States established their Office of Women's Health around this time, in 1991, concentrating on the underrepresentation of women in research, especially with CVD.[120]

- In 1993, the FDA created a guide for researchers to follow when including women in their studies, with an updated action plan for this published in 2014.[121][122] It is important to note that the 1993 policy effectively reversed one established in 1977 that called on fertile women to be excluded from clinical trials, which had furthered the lack of women present in research at the time.[123] This was done to address concerns of birth defects among infants and changes in estrogen and progesterone in postmenopausal women. Between 1988 and 1991, only 50% of the data analysis from trials that were not designed for women, accounted for the difference in gender. It was assumed that the drugs given to men would work if prescribed to women.[17]

- The Institute of Medicine, also from the United States, moved forward with other milestones by publishing papers in 2001 and 2010 that recognized sex and gender for the first time as variables crucial in women's health.[124]

- Also in 2010, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Canadian Institute of Gender and Health produced a tool to make incorporating sex and gender as variables easier in research.[125]

- This was followed shortly by the World Health Organization, which in 2014, promoted more gender-specific approaches to data analysis and health-inequality monitoring to ensure that a more sustainable approach was taken to this research.[126]

- In 2015, the National Institutes of Health and the United Nations both endorsed the necessity for gender-specific reporting or providing a reason for why it was not included in studies to ensure that researchers are held accountable.[127][128] The United Nations specifically advocated for gender-sensitive strategies to be established by 2030.

- Following in North America's footsteps, the League of European Research Universities proposed a list of suggestions for how to undertake gender-specific research for universities, governments, and more.[129]

- In 2016, two vital reports from Oxford and the United Nations, "Women's health: a new global agenda" and "Global Strategy for Women's, Children's, and Adolescents' Health (2016–2030)", were published, bringing much-needed attention to this issue.[130][131]

- The European Commission in 2016 provided a published guide for Horizon 2020 to address participation gaps for women in research and strategies to approach this.[132]

These are not the only steps that have been taken to include women in the scientific community. There have been numerous policies and practices already established and continuing to be added to address the growing concern of CVD.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention division of heart disease and stroke prevention initiated the Well-Integrated Screening and Evaluation for WOMen Across the Nation (WISEWOMAN) awareness campaign in 1993.[133] It was created to educate women on the risk factors associated with CVD and encourage healthier lifestyles to limit that risk.

- In 1999, the AHA created the Guide to preventive cardiology for women guideline to be used by the scientific community.[134] This was the first of its kind in advising CVD management in women.

- In 2004, the 1999 guideline was replaced by the Evidence-based guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in women by the American Heart Association.[135] These guidelines underlined the importance of including women in research and challenged the notion that men and women are the same for CVD pathogenesis and these differences should encourage research and treatment to be approached accordingly. There were additional updates to this in 2007 and 2011.

- The European Society of Cardiology and European Health Network in 2006 started the transnational project for the prevention and management of CVD, where its objective was to "Address the significant burden of CVD in Europe and to determine specific areas of intervention to contribute to preventing avoidable deaths and disability".[136]

- The Hellenic Cardiac Society, a European organization, followed this up with a national action plan for CVD projected for 2008 to 2012. Its aim, through the American Heart Association and many other guidelines, was to prevent CVD, primarily heart disease and stroke.[137]

- In 2011, the American House of Representatives put forward huge legislation called the "Heart Disease, Education, Analysis, Research, Treatment for Women Act or Heart for Women Act".[138] This is intended to provide healthcare professionals and others with gender-specific information for appropriate medical treatments.

- Also in 2011, the European Society of Cardiology released guidelines for the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy: the Task Force on the Management of Cardiovascular Diseases During Pregnancy of the European Society of Cardiology.[139] As pregnancy is a crucial unique factor to consider in women, these guidelines encouraged the scientific community to be able to tailor treatment plans accordingly. There was one update to this made in 2018.

- The Journal of American College of Cardiology released a state-of-the-art review in 2017 called "Quality and equitable health care gaps for women: attributions to sex differences in cardiovascular medicine".[140] This discussed the quality and equity of health care received by women.

- In that same year, the released survey results that provided insight into the awareness within healthcare providers, and the gaps present in the research and clinical applications thus far.[141]

References

- Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, et al. (March 2018). "Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2018 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association". Circulation. 137 (12): e67–e492. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000558. PMID 29386200. S2CID 3308716.

- Roth GA, Johnson C, Abajobir A, Abd-Allah F, Abera SF, Abyu G, et al. (July 2017). "Global, Regional, and National Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases for 10 Causes, 1990 to 2015". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 70 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.052. PMC 5491406. PMID 28527533.

- Know the Differences

- "The top 10 causes of death". www.who.int. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- "A History of Women's Heart Health". American College of Cardiology. Archived from the original on 2020-12-03. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

- Coulter, Stephanie A. (2011). "Epidemiology of Cardiovascular Disease in Women". Texas Heart Institute Journal. 38 (2): 145–147. ISSN 0730-2347. PMC 3066813. PMID 21494522.

- Worrall-Carter L, Ski C, Scruth E, Campbell M, Page K (December 2011). "Systematic review of cardiovascular disease in women: assessing the risk". Nursing & Health Sciences. 13 (4): 529–535. doi:10.1111/j.1442-2018.2011.00645.x. PMID 22070582.

- "How heart disease is different for women". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2022-09-12.

- Filbey L, Khan MS, Van Spall HG (January 2022). "Protection by inclusion: Increasing enrollment of women in cardiovascular trials". American Heart Journal Plus: Cardiology Research and Practice. 13: 100091. doi:10.1016/j.ahjo.2022.100091. ISSN 2666-6022. S2CID 246453881.

- Saeed A, Kampangkaew J, Nambi V (2017-10-01). "Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Women". Methodist DeBakey Cardiovascular Journal. 13 (4): 185–192. doi:10.14797/mdcj-13-4-185. PMC 5935277. PMID 29744010.

- Dart A (2002-02-15). "Gender, sex hormones and autonomic nervous control of the cardiovascular system". Cardiovascular Research. 53 (3): 678–687. doi:10.1016/S0008-6363(01)00508-9. PMID 11861039. S2CID 19013807.

- Robertson RM (May 2001). "Women and cardiovascular disease: the risks of misperception and the need for action". Circulation. 103 (19): 2318–2320. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.103.19.2318. PMID 11352875.

- "Off-Campus Access: Login to e-Resources - McMaster Libraries". libraryssl.lib.mcmaster.ca. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- Thomas JL, Braus PA (February 1998). "Coronary artery disease in women. A historical perspective". Archives of Internal Medicine. 158 (4): 333–337. doi:10.1001/archinte.158.4.333. PMID 9487230.

- Mosca L, Hammond G, Mochari-Greenberger H, Towfighi A, Albert MA (March 2013). "Fifteen-year trends in awareness of heart disease in women: results of a 2012 American Heart Association national survey". Circulation. 127 (11): 1254–63, e1-29. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e318287cf2f. PMC 3684065. PMID 23429926.

- Cushman M, Shay CM, Howard VJ, Jiménez MC, Lewey J, McSweeney JC, et al. (February 2021). "Ten-Year Differences in Women's Awareness Related to Coronary Heart Disease: Results of the 2019 American Heart Association National Survey: A Special Report From the American Heart Association". Circulation. 143 (7): e239–e248. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000907. PMID 32954796. S2CID 221828897.

- Thomas JL, Braus PA (February 1998). "Coronary artery disease in women. A historical perspective". Archives of Internal Medicine. 158 (4): 333–337. doi:10.1001/archinte.158.4.333. PMID 9487230.

- Christian AH, Rosamond W, White AR, Mosca L (2007-01-01). "Nine-year trends and racial and ethnic disparities in women's awareness of heart disease and stroke: an American Heart Association national study". Journal of Women's Health. 16 (1): 68–81. doi:10.1089/jwh.2006.M072. PMID 17274739.

- Mochari-Greenberger H, Mills T, Simpson SL, Mosca L (July 2010). "Knowledge, preventive action, and barriers to cardiovascular disease prevention by race and ethnicity in women: an American Heart Association national survey". Journal of Women's Health. 19 (7): 1243–1249. doi:10.1089/jwh.2009.1749. PMC 3129688. PMID 20575620.

- Kurian A (2007). "Racial and Ethnic Differences in Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors: A Systematic Review". Ethnicity & Disease. 17 (1): 143–152. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.483.4467. PMID 17274224.

- Villablanca AC, Slee C, Lianov L, Tancredi D (November 2016). "Outcomes of a Clinic-Based Educational Intervention for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention by Race, Ethnicity, and Urban/Rural Status". Journal of Women's Health. 25 (11): 1174–1186. doi:10.1089/jwh.2015.5387. PMC 5116690. PMID 27356155.

- "What is an Arrhythmia?".

- "Heart arrhythmia - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- "Women & Abnormal Heart Beats". Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- CDC (2021-07-19). "Coronary Artery Disease | cdc.gov". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- "Coronary Artery Disease: Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis & Treatments". Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- Starkman E. "Coronary Artery Disease: It's Different for Women". WebMD. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- "Heart failure - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- "Heart Failure (Congestive Heart Failure): Symptoms & Treatment". Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- "Is It Congestive Heart Failure?". Healthline. 2021-06-02. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- "Heart Failure in Women". Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- "Heart Attack: What Is It, Causes, Symptoms & Treatment". Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- "Peripheral artery disease (PAD) - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- "Peripheral Vascular Disease: Causes, Symptoms & Treatment". Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- "Stroke: Causes, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment". www.medicalnewstoday.com. 2020-03-12. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- "16 Symptoms of Stroke in Women: Treatment, and Prevention". Healthline. 2016-12-23. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- CDC (2019-12-09). "Valvular Heart Disease | cdc.gov". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- "Valve Disease in Women". Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery. 2012-10-26. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- Martínez-Sellés M, García-Fernández MA, Moreno M, Larios E, García-Robles JA, Pinto A (December 2006). "[Influence of gender on the etiology of mitral regurgitation]". Revista Espanola de Cardiologia (in Spanish). 59 (12): 1335–1338. doi:10.1016/S1885-5857(07)60091-7. PMID 17194432. S2CID 18828094.

- Bots SH, Peters SA, Woodward M (2017-03-01). "Sex differences in coronary heart disease and stroke mortality: a global assessment of the effect of ageing between 1980 and 2010". BMJ Global Health. 2 (2): e000298. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000298. PMC 5435266. PMID 28589033.

- Gao Z, Chen Z, Sun A, Deng X (2019-12-01). "Gender differences in cardiovascular disease". Medicine in Novel Technology and Devices. 4: 100025. doi:10.1016/j.medntd.2019.100025. ISSN 2590-0935. S2CID 213913231.

- Mosca L, Barrett-Connor E, Wenger NK (November 2011). "Sex/gender differences in cardiovascular disease prevention: what a difference a decade makes". Circulation. 124 (19): 2145–2154. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.968792. PMC 3362050. PMID 22064958.

- Garcia M, Mulvagh SL, Merz CN, Buring JE, Manson JE (April 2016). "Cardiovascular Disease in Women: Clinical Perspectives". Circulation Research. 118 (8): 1273–1293. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.307547. PMC 4834856. PMID 27081110.

- Keteepe-Arachi T, Sharma S (August 2017). "Cardiovascular Disease in Women: Understanding Symptoms and Risk Factors". European Cardiology. 12 (1): 10–13. doi:10.15420/ecr.2016:32:1. PMC 6206467. PMID 30416543.

- Wattanapitayakul SK, Bauer JA (February 2001). "Oxidative pathways in cardiovascular disease: roles, mechanisms, and therapeutic implications". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 89 (2): 187–206. doi:10.1016/S0163-7258(00)00114-5. PMID 11316520.

- Taverne YJ, Bogers AJ, Duncker DJ, Merkus D (2013-04-22). "Reactive oxygen species and the cardiovascular system". Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2013: 862423. doi:10.1155/2013/862423. PMC 3655680. PMID 23738043.

- Montezano AC, Touyz RM (May 2012). "Molecular mechanisms of hypertension--reactive oxygen species and antioxidants: a basic science update for the clinician". The Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 28 (3): 288–295. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2012.01.017. PMID 22445098.

- Ballinger SW (May 2005). "Mitochondrial dysfunction in cardiovascular disease". Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 38 (10): 1278–1295. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.02.014. PMID 15855047.

- "NADPH Oxidase - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- Kostić DA, Dimitrijević DS, Stojanović GS, Palić IR, Đorđević AS, Ickovski JD (February 2015). "Xanthine Oxidase: Isolation, Assays of Activity, and Inhibition". Journal of Chemistry. 2015: e294858. doi:10.1155/2015/294858. ISSN 2090-9063.

- "Nitric Oxide Synthase - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- Fernandez-Marcos PJ, Nóbrega-Pereira S (August 2016). "NADPH: new oxygen for the ROS theory of aging". Oncotarget. 7 (32): 50814–50815. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.10744. PMC 5239434. PMID 27449104.

- Dan Dunn J, Alvarez LA, Zhang X, Soldati T (December 2015). "Reactive oxygen species and mitochondria: A nexus of cellular homeostasis". Redox Biology. 6: 472–485. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2015.09.005. PMC 4596921. PMID 26432659.

- Ballinger SW (May 2005). "Mitochondrial dysfunction in cardiovascular disease". Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 38 (10): 1278–1295. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.02.014. PMID 15855047.

- Mehra VC, Ramgolam VS, Bender JR (October 2005). "Cytokines and cardiovascular disease". Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 78 (4): 805–818. doi:10.1189/jlb.0405182. PMID 16006537. S2CID 14446117.

- Amin MN, Siddiqui SA, Ibrahim M, Hakim ML, Ahammed MS, Kabir A, Sultana F (January 2020). "Inflammatory cytokines in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease and cancer". SAGE Open Medicine. 8: 2050312120965752. doi:10.1177/2050312120965752. PMC 7594225. PMID 33194199.

- Schenck-Gustafsson, Karin (2009-07-20). "Risk factors for cardiovascular disease in women". Maturitas. 63 (3): 186–190. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.02.014. ISSN 0378-5122.

- Schenck-Gustafsson, Karin (2009-07-20). "Risk factors for cardiovascular disease in women". Maturitas. 63 (3): 186–190. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.02.014. ISSN 0378-5122.

- Saeed A, Kampangkaew J, Nambi V (2017). "Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Women". Methodist DeBakey Cardiovascular Journal. 13 (4): 185–192. doi:10.14797/mdcj-13-4-185. PMC 5935277. PMID 29744010.

- Schenck-Gustafsson, Karin (2009-07-20). "Risk factors for cardiovascular disease in women". Maturitas. 63 (3): 186–190. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.02.014. ISSN 0378-5122.

- "Global Health Risks: Mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks" (PDF).

- Cho L, Davis M, Elgendy I, Epps K, Lindley KJ, Mehta PK, et al. (May 2020). "Summary of Updated Recommendations for Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Women: JACC State-of-the-Art Review". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 75 (20): 2602–2618. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.060. PMC 8328156. PMID 32439010.

- Gudmundsdottir H, Høieggen A, Stenehjem A, Waldum B, Os I (May 2012). "Hypertension in women: latest findings and clinical implications". Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease. 3 (3): 137–46. doi:10.1177/2040622312438935. PMC 3513905. PMID 23251774.

- CDC (2020-01-31). "LDL and HDL Cholesterol: "Bad" and "Good" Cholesterol". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2022-09-12.

- Linton, MacRae F.; Yancey, Patricia G.; Davies, Sean S.; Jerome, W. Gray; Linton, Edward F.; Song, Wenliang L.; Doran, Amanda C.; Vickers, Kasey C. (2000), Feingold, Kenneth R.; Anawalt, Bradley; Boyce, Alison; Chrousos, George (eds.), "The Role of Lipids and Lipoproteins in Atherosclerosis", Endotext, South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc., PMID 26844337, retrieved 2022-09-12

- "Heart Disease and Diabetes". WebMD. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- Maric C (December 2010). "Risk factors for cardiovascular disease in women with diabetes". Gender Medicine. 7 (6): 551–556. doi:10.1016/j.genm.2010.11.007. PMC 3179621. PMID 21195355.

- Cho L, Davis M, Elgendy I, Epps K, Lindley KJ, Mehta PK, et al. (May 2020). "Summary of Updated Recommendations for Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Women: JACC State-of-the-Art Review". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 75 (20): 2602–2618. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.060. PMC 8328156. PMID 32439010.

- Robbins CL, Hutchings Y, Dietz PM, Kuklina EV, Callaghan WM (April 2014). "History of preterm birth and subsequent cardiovascular disease: a systematic review". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 210 (4): 285–297. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2013.09.020. PMC 4387871. PMID 24055578.

- Demicheva E, Crispi F (2014). "Long-term follow-up of intrauterine growth restriction: cardiovascular disorders". Fetal Diagnosis and Therapy. 36 (2): 143–153. doi:10.1159/000353633. PMID 23948759. S2CID 3052187.

- Archer DF (2009-01-01). "Premature menopause increases cardiovascular risk". Climacteric. 12 (Suppl 1): 26–31. doi:10.1080/13697130903013452. PMID 19811237. S2CID 34269947.

- Schenck-Gustafsson K (July 2009). "Risk factors for cardiovascular disease in women". Maturitas. 63 (3): 186–190. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.02.014. PMID 19403246.

- "Exercise and the Heart". www.hopkinsmedicine.org. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- Blair SN, Kohl HW, Paffenbarger RS, Clark DG, Cooper KH, Gibbons LW (November 1989). "Physical fitness and all-cause mortality. A prospective study of healthy men and women". JAMA. 262 (17): 2395–2401. doi:10.1001/jama.1989.03430170057028. PMID 2795824.

- Winkleby MA, Kraemer HC, Ahn DK, Varady AN (1998-07-22). "Ethnic and socioeconomic differences in cardiovascular disease risk factors: findings for women from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994". JAMA. 280 (4): 356–362. doi:10.1001/jama.280.4.356. PMID 9686553. S2CID 25863964.

- ESHRE Capri Workshop Group (2006). "Hormones and cardiovascular health in women". Human Reproduction Update. 12 (5): 483–497. doi:10.1093/humupd/dml028. PMID 16807276.

- Clark AM, DesMeules M, Luo W, Duncan AS, Wielgosz A (November 2009). "Socioeconomic status and cardiovascular disease: risks and implications for care". Nature Reviews. Cardiology. 6 (11): 712–722. doi:10.1038/nrcardio.2009.163. PMID 19770848. S2CID 21835944.

- Perk J, De Backer G, Gohlke H, Graham I, Reiner Z, Verschuren WM, et al. (December 2012). "European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012) : the fifth joint task force of the European society of cardiology and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts)". International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 19 (4): 403–488. doi:10.1007/s12529-012-9242-5. PMID 23093473. S2CID 195247788.

- Albert PR (July 2015). "Why is depression more prevalent in women?". Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience. 40 (4): 219–221. doi:10.1503/jpn.150205. PMC 4478054. PMID 26107348.

- "Dealing with breast cancer means also keeping in mind heart health". www.heart.org. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- Martis RJ, Acharya UR, Adeli H (May 2014). "Current methods in electrocardiogram characterization". Computers in Biology and Medicine. 48: 133–149. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2014.02.012. PMID 24681634.

- "Echocardiogram".

- "Holter monitor". Mayo Clinic.

- "Heart MRI". Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- "Stress test - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- "Nuclear stress test - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- "Cardiac Catheterization and Coronary Angiography - Heart and Blood Vessel Disorders - Merck Manuals Consumer Version". Merck Manuals Consumer Version. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- Misra S, Stevermer JJ (January 2009). "ACE inhibitors and ARBs: one or the other--not both--for high-risk patients". The Journal of Family Practice. 58 (1): 24–7. PMC 3183919. PMID 19141267.

- Cheng J, Zhang W, Zhang X, Han F, Li X, He X, et al. (May 2014). "Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers on all-cause mortality, cardiovascular deaths, and cardiovascular events in patients with diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis". JAMA Internal Medicine. 174 (5): 773–785. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.348. PMID 24687000.

- "Collaborative overview of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy--I: Prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke by prolonged antiplatelet therapy in various categories of patients. Antiplatelet Trialists' Collaboration". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 308 (6921): 81–106. January 1994. doi:10.1136/bmj.308.6921.81. PMC 2539220. PMID 8298418.

- Ridker PM, Cook NR, Lee IM, Gordon D, Gaziano JM, Manson JE, et al. (March 2005). "A randomized trial of low-dose aspirin in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in women". The New England Journal of Medicine. 352 (13): 1293–1304. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa050613. PMID 15753114.

- Bugiardini R, Yoon J, Kedev S, Stankovic G, Vasiljevic Z, Miličić D, et al. (September 2020). "Prior Beta-Blocker Therapy for Hypertension and Sex-Based Differences in Heart Failure Among Patients With Incident Coronary Heart Disease". Hypertension. 76 (3): 819–826. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15323. PMID 32654558. S2CID 220499607.

- American Heart Association. "Women taking beta blockers for hypertension may have higher risk of heart failure with acute coronary syndrome". medicalxpress.com. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- "Blood Thinners". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- Zannad F, Anker SD, Byra WM, Cleland JG, Fu M, Gheorghiade M, et al. (October 2018). "Rivaroxaban in Patients with Heart Failure, Sinus Rhythm, and Coronary Disease". The New England Journal of Medicine. 379 (14): 1332–1342. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1808848. PMID 30146935. S2CID 52090066.

- Elliott WJ, Ram CV (September 2011). "Calcium channel blockers". Journal of Clinical Hypertension (Greenwich, Conn.). 13 (9): 687–9. doi:10.1111/j.1751-7176.2011.00513.x. PMC 8108866. PMID 21896151.

- Ramanlal R, Gupta V (January 2022). "Physiology, Vasodilation". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.

- Felker GM, Ellison DH, Mullens W, Cox ZL, Testani JM (March 2020). "Diuretic Therapy for Patients With Heart Failure: JACC State-of-the-Art Review". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 75 (10): 1178–1195. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2019.12.059. PMID 32164892. S2CID 212691328.

- Shah, S. U.; Anjum, S.; Littler, W. A. (2004). "Use of diuretics in cardiovascular diseases: (1) heart failure". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 80 (942): 201–205. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2003.010835. PMC 1742985. PMID 15082840.

- "Hormone therapy: Is it right for you?". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- Boardman HM, Hartley L, Eisinga A, Main C, Roqué i Figuls M, Bonfill Cosp X, et al. (Cochrane Heart Group) (March 2015). "Hormone therapy for preventing cardiovascular disease in post-menopausal women". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD002229. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002229.pub4. PMID 25754617.

- Divakaran S, Loscalzo J (November 2017). "The Role of Nitroglycerin and Other Nitrogen Oxides in Cardiovascular Therapeutics". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 70 (19): 2393–2410. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.09.1064. PMC 5687289. PMID 29096811.

- "Statins: Are these cholesterol-lowering drugs right for you?". Mayo Clinic.

- Taylor FC, Huffman M, Ebrahim S (December 2013). "Statin therapy for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease". JAMA. 310 (22): 2451–2452. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.281348. PMID 24276813.

- Bove AA (2016-04-01). "Exercise and Heart Disease". Methodist DeBakey Cardiovascular Journal. 12 (2): 74–75. doi:10.14797/mdcj-12-2-74. PMC 4969029. PMID 27486487.

- Yu E, Rimm E, Qi L, Rexrode K, Albert CM, Sun Q, et al. (September 2016). "Diet, Lifestyle, Biomarkers, Genetic Factors, and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in the Nurses' Health Studies". American Journal of Public Health. 106 (9): 1616–1623. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2016.303316. PMC 4981798. PMID 27459449.

- Kondo T, Nakano Y, Adachi S, Murohara T (September 2019). "Effects of Tobacco Smoking on Cardiovascular Disease". Circulation Journal. 83 (10): 1980–1985. doi:10.1253/circj.CJ-19-0323. PMID 31462607. S2CID 201667019.

- Mosca L, Manson JE, Sutherland SE, Langer RD, Manolio T, Barrett-Connor E (October 1997). "Cardiovascular disease in women: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Writing Group". Circulation. 96 (7): 2468–2482. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.96.7.2468. PMID 9337227.

- "Coronary angioplasty and stent insertion". nhs.uk. 2017-10-24. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- "Coronary artery bypass graft". 24 October 2017.

- "Heart Transplantation Procedure - Health Encyclopedia - University of Rochester Medical Center". www.urmc.rochester.edu. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- Gholizadeh L, Davidson P (January 2008). "More similarities than differences: an international comparison of CVD mortality and risk factors in women". Health Care for Women International. 29 (1): 3–22. doi:10.1080/07399330701723756. hdl:10453/9479. PMID 18176877. S2CID 6553135.

- Roth GA, Johnson C, Abajobir A, Abd-Allah F, Abera SF, Abyu G, et al. (July 2017). "Global, Regional, and National Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases for 10 Causes, 1990 to 2015". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 70 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.052. PMC 5491406. PMID 28527533.

- "Cardiovascular Disease: Women's No. 1 Health Threat" (PDF). American Heart Association. March 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-07-14. Retrieved 2021-11-17.

- Zhang Y (July 2010). "Cardiovascular diseases in American women". Nutrition, Metabolism, and Cardiovascular Diseases. 20 (6): 386–393. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2010.02.001. PMC 4039306. PMID 20554179.

- Stramba-Badiale M, Fox KM, Priori SG, Collins P, Daly C, Graham I, et al. (April 2006). "Cardiovascular diseases in women: a statement from the policy conference of the European Society of Cardiology". European Heart Journal. 27 (8): 994–1005. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehi819. PMID 16522654.

- Gholizadeh L, Davidson P (January 2008). "More similarities than differences: an international comparison of CVD mortality and risk factors in women". Health Care for Women International. 29 (1): 3–22. doi:10.1080/07399330701723756. hdl:10453/9479. PMID 18176877. S2CID 6553135.

- CDC (2020-01-31). "Women and Heart Disease". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2021-11-17.

- "NIH Guide: NIH GUIDELINES ON THE INCLUSION OF WOMEN AND MINORITIES AS SUBJECTS IN CLINICAL RESEARCH". grants.nih.gov. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- "Vision, mission, goals, and history | Office on Women's Health". www.womenshealth.gov. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- Angell M (2010-01-15). "Caring for Women's Health -- What Is the Problem?". New England Journal of Medicine. 329 (4): 271–272. doi:10.1056/NEJM199307223290409. PMID 8316272.

- Elahi M, Eshera N, Bambata N, Barr H, Lyn-Cook B, Beitz J, et al. (March 2016). "The Food and Drug Administration Office of Women's Health: Impact of Science on Regulatory Policy: An Update". Journal of Women's Health. 25 (3): 222–234. doi:10.1089/jwh.2015.5671. PMC 4790210. PMID 26871618.

- Wood SF (October 2005). "Women's health and the FDA". The New England Journal of Medicine. 353 (16): 1650–1651. doi:10.1056/NEJMp058225. PMID 16236734.

- Smith Taylor, Julie (2011-05-04). "Women's Health Research: Progress, Pitfalls, and Promise". Health Care for Women International. 32 (6): 555–556. doi:10.1080/07399332.2011.562837. PMID 21547806. S2CID 216591752.

- "How to integrate sex and gender into research - CIHR". Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Government of Canada. 2018-02-12. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- Kouvari M, Souliotis K, Yannakoulia M, Panagiotakos DB (2020-10-12). "Cardiovascular Diseases in Women: Policies and Practices Around the Globe to Achieve Gender Equity in Cardiac Health". Risk Management and Healthcare Policy. 13: 2079–2094. doi:10.2147/RMHP.S264672. PMC 7567535. PMID 33116988.

- "NOT-OD-15-102: Consideration of Sex as a Biological Variable in NIH-funded Research". grants.nih.gov. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- "Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development | Department of Economic and Social Affairs". sdgs.un.org. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- "The League of European Research Universities analyses the role of gender and sex analysis in research and innovation • European Platform of Women Scientists EPWS". European Platform of Women Scientists EPWS. 2015-09-20. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- Global Strategy for Women's, Children's and Adolescents' Health (2016–2030): early childhood development: report by the Director-General. World Health Assembly (Report). World Health Organization. 10 May 2018. hdl:10665/276423.

- Norton R. "Women's Health: A New Global Agenda" (PDF).

- "H2020 Programme: Guidance on Gender Equality in Horizon 2020" (PDF).

- "WISEWOMAN Home | cdc.gov". www.cdc.gov. 2020-02-10. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- Mosca L, Grundy SM, Judelson D, King K, Limacher M, Oparil S, et al. (May 1999). "AHA/ACC scientific statement: consensus panel statement. Guide to preventive cardiology for women. American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 33 (6): 1751–1755. doi:10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00190-4. PMID 10334455.

- Mosca L, Appel LJ, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, Chandra-Strobos N, Fabunmi RP, et al. (February 2004). "Evidence-based guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in women". Circulation. 109 (5): 672–693. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000114834.85476.81. PMID 14761900. S2CID 29202135.

- "About". ehnheart.org. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- "Update to a Public Health Action Plan to Prevent Heart Disease and Stroke" (PDF).

- "Text of H.R. 1032 (111th): Heart Disease Education, Analysis Research, and Treatment for Women Act (Passed the House version)". GovTrack.us. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- Regitz-Zagrosek V, Blomstrom Lundqvist C, Borghi C, Cifkova R, Ferreira R, Foidart JM, et al. (December 2011). "ESC Guidelines on the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy: the Task Force on the Management of Cardiovascular Diseases during Pregnancy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)". European Heart Journal. 32 (24): 3147–3197. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehr218. PMID 21873418.

- Shaw LJ, Pepine CJ, Xie J, Mehta PK, Morris AA, Dickert NW, et al. (July 2017). "Quality and Equitable Health Care Gaps for Women: Attributions to Sex Differences in Cardiovascular Medicine". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 70 (3): 373–388. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.05.051. PMID 28705320. S2CID 36258377.

- Bairey Merz CN, Andersen H, Sprague E, Burns A, Keida M, Walsh MN, et al. (July 2017). "Knowledge, Attitudes, and Beliefs Regarding Cardiovascular Disease in Women: The Women's Heart Alliance". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 70 (2): 123–132. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.05.024. PMID 28648386.

Further reading

- Go Red for Women

- FDA Regulations, Guidance, and Reports related to Women's Health

- Coronary heart disease in Western Collaborative Group Study. Final follow-up experience of 8 1/2 years

- Sex/Gender Differences in Cardiovascular Disease Prevention What a Difference a Decade Makes

- Women & Cardiovascular Diseases