Cataract surgery

Cataract surgery, also called lens replacement surgery, is the removal of the natural lens of the eye (also called "crystalline lens") that has developed an opacification, which is referred to as a cataract,[1] and its replacement with an intraocular lens. Metabolic changes of the crystalline lens fibers over time lead to the development of the cataract, causing impairment or loss of vision. Some infants are born with congenital cataracts, and certain environmental factors may also lead to cataract formation. Early symptoms may include strong glare from lights and small light sources at night, and reduced acuity at low light levels.

| Cataract surgery | |

|---|---|

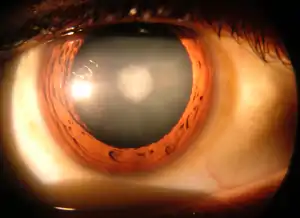

Magnified view of a cataract in a human eye seen on examination with a slit lamp | |

| Specialty | Ophthalmology |

| ICD-9-CM | 13.19 |

| MeSH | D002387 |

| MedlinePlus | 002957 |

During cataract surgery, a patient's cloudy natural cataract lens is removed, either by emulsification in place or by cutting it out. An artificial intraocular lens (IOL) is implanted in its place. Cataract surgery is generally performed by an ophthalmologist in an ambulatory setting at a surgical center or hospital rather than an inpatient setting. Either topical, sub-tenon, peribulbar, or retrobulbar local anesthesia is used, usually causing little or no discomfort to the patient.[2]

Well over 90% of operations are successful in restoring useful vision, with a low complication rate. Day care, high volume, minimally invasive, small incision phacoemulsification with quick post-op recovery has become the standard of care in cataract surgery all over the world.

Types

Two main types of surgical procedures are in common use throughout the world. The first procedure is phacoemulsification (phaco) and the second involves two different types of extracapsular cataract extraction (ECCE). In most surgeries, an intraocular lens is inserted. Foldable lenses are generally used for the 2–3 mm phaco incision, while non-foldable lenses are placed through the larger extracapsular incision. The small incision size used in phacoemulsification (2–3 mm) often allows "sutureless" incision closure. ECCE uses a larger incision (10–12 mm) and therefore usually requires stitching, and this in part led to the modification of ECCE known as manual small incision cataract surgery (MSICS).

Cataract extraction using intracapsular cataract extraction (ICCE) has been superseded by phacoemulsification and ECCE, and is rarely performed.

Phacoemulsification is the most commonly performed cataract procedure in the developed world. However, the high cost of a phacoemulsification machine and of the associated disposable equipment means that ECCE and MSICS remain the most commonly performed procedure in developing countries.

Cataract surgery is commonly done as day care rather than in-patient procedure as there is some evidence that day surgery has similar outcomes and is cheaper than hospitalisation and overnight stay.[3]

Types of surgery

There are a number of different surgical techniques used in cataract surgery:

- Phacoemulsification (phaco) is the most common technique used in developed countries. It involves the use of a machine with an ultrasonic handpiece equipped with a titanium or steel tip. The tip vibrates at ultrasonic frequency (40,000 Hz) and the lens material is emulsified. A second fine instrument (sometimes called a "cracker" or "chopper") may be used from a side port to facilitate cracking or chopping of the nucleus into smaller pieces. Fragmentation into smaller pieces makes emulsification easier, as well as the aspiration of cortical material (soft part of the lens around the nucleus). After phacoemulsification of the lens nucleus and cortical material is completed, a dual irrigation-aspiration (I-A) probe or a bimanual I-A system is used to aspirate out the remaining peripheral cortical material.

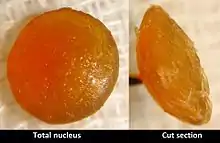

- Manual small incision cataract surgery (MSICS): This technique is an evolution of ECCE (see below) where the entire lens is expressed out of the eye through a self-sealing scleral tunnel wound. An appropriately constructed scleral tunnel is watertight and does not require suturing. The "small" in the title refers to the wound being relatively smaller than an ECCE, although it is still markedly larger than a phaco wound. Head-to-head trials of MSICS vs phaco in dense cataracts have found no difference in outcomes, but shorter operating time and significantly lower costs with MSICS.[4]

- Extracapsular cataract extraction (ECCE): Extracapsular cataract extraction involves the removal of almost the entire natural lens while the elastic lens capsule (posterior capsule) is left intact to allow implantation of an intraocular lens.[5] It involves manual expression of the lens through a large (usually 10–12 mm) incision made in the cornea or sclera. Although it requires a larger incision and the use of stitches, the conventional method may be indicated for patients with very hard cataracts or other situations in which phacoemulsification is problematic.

- Intracapsular cataract extraction (ICCE) involves the removal of the lens and the surrounding lens capsule in one piece. The procedure has a relatively high rate of complications due to the large incision required and pressure placed on the vitreous body. It has therefore been largely superseded and is rarely performed in countries where operating microscopes and high-technology equipment are readily available.[5] After lens removal, an artificial plastic lens (an intraocular lens implant) can be placed in either the anterior chamber or sutured into the sulcus.

- Femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery has been shown to have no visual, refractive or safety benefit over manual phacoemulsification.[6][7]

Cryoextraction is a form of ICCE that freezes the lens with a cryogenic substance such as liquid nitrogen.[8] In this technique, the cataract is extracted through use of a cryoextractor – a cryoprobe whose refrigerated tip adheres to and freezes tissue of the lens, permitting its removal. Although it is now used primarily for the removal of subluxated lenses, it was the favored form of cataract extraction from the late 1960s to the early 1980s.[9]

Intraocular lenses

- Intraocular lens (IOL) implantation: After the removal of the cataract, an IOL is usually implanted into the eye, either through a small incision (1.8 mm to 2.8 mm) using a foldable IOL, or through an enlarged incision, using a poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) lens. The foldable IOL, made of silicone or acrylic material of appropriate power is folded either using a holder/folder, or a proprietary insertion device provided along with the IOL. The lens implanted is inserted through the incision into the capsular bag within the posterior chamber (in-the-bag implantation). Sometimes, a sulcus implantation (in front or on top of the capsular bag but behind the iris) may be required because of posterior capsular tears or because of zonulodialysis. Implantation of posterior chamber IOL (PCIOL) in patients below 1 year of age is controversial due to rapid ocular growth at this age and the excessive amount of inflammation, which may be very difficult to control. Optical correction in these patients without intraocular lens (aphakic) is usually managed with either special contact lenses or glasses. Secondary implantation of IOL (placement of a lens implant as a second operation) may be considered later. New designs of multifocal intraocular lens are now available. These lenses allow focusing of rays from distant as well as near objects, working much like bifocal or trifocal eyeglasses. Preoperative patient selection and good counselling is extremely important to avoid unrealistic expectations and post-operative patient dissatisfaction. Acceptability for these lenses has become better and studies have shown good results in selected patients.

In addition, there is an accommodating lens that was approved by the US FDA in 2003 and made by Eyeonics,[10] now Bausch & Lomb. The Crystalens is on struts and is implanted in the eye's lens capsule, and its design allows the lens' focusing muscles to move it back and forth, giving the patient natural focusing ability.

Artificial intraocular lenses (IOLs) are used to replace the eye's natural lens that is removed during cataract surgery. These lenses have been increasing in popularity since the 1960s, but it was not until 1981 that the first U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for this type of product was issued. The development of IOLs brought about an innovation as patients previously did not have their natural lens replaced and as a result had to wear very thick eyeglasses or some special type of contact lenses. Presently, IOLs are especially designed for patients with different vision problems. The main types of IOLs that now exist are divided into monofocal and multifocal lenses.

The monofocal intraocular lenses are the traditional ones, which provide vision at one distance only: far, intermediate, or near. Patients who choose these lenses over the more developed types will probably need to wear eyeglasses or contact lenses for reading or using the computer. These intraocular lenses are usually spherical, and they have their surface uniformly curved.[11]

The multifocal intraocular lens is one of the newest types of such lenses. They are often referred to as "premium" lenses because they are multifocal and accommodative, and allow the patient to visualize objects at more than one distance, removing the need to wear eyeglasses or contact lenses. Premium intraocular lenses are those used in correcting presbyopia or astigmatism. Premium intraocular lenses are more expensive and are typically not covered, or not fully covered, by health insurance, as their additional benefits are considered a luxury and not a medical necessity. An accommodative intraocular lens implant has only one focal point, but it acts as if it is a multifocal IOL. The intraocular lens was designed with a hinge similar to the mechanics of the eye's natural lens.

The intraocular lenses used in correcting astigmatism are called toric, and have been FDA approved since 1998. The STAAR Surgical Intraocular Lens was the first such lens developed in the United States and it may correct up to 3.5 diopters. A different model of toric lenses was created by Alcon and may correct up to 3 diopters of astigmatism. In order to achieve the most benefit from a toric lens, the surgeon must rotate the lens to be on axis with the patient's astigmatism. Intraoperative wavefront analysis, such as that provided by the ORA System developed by Wavetec Visions Systems, can be used to assist the doctor in toric lens placement and minimize astigmatic errors.[12]

Cataract surgery may be performed to correct vision problems in both eyes, and in these cases, patients are usually advised to consider monovision. This procedure involves inserting in one eye an intraocular lens that provides near vision and in the other eye an IOL that provides distance vision. Although most patients can adjust to having implanted monofocal lenses in both eyes, some cannot and may experience blurred vision at both near and far distances. IOLs that emphasize distance vision may be mixed with IOLs that emphasize intermediate vision in order to achieve a type of modified monovision. Bausch and Lomb developed in 2004 the first aspheric IOLs, which provide better contrast sensitivity by having their periphery flatter than the middle of the lens. However, some cataract surgeons have questioned the benefits of aspheric IOLs, because the contrast sensitivity benefit may not last in older patients.

Some of the newly launched IOLs are able to provide ultraviolet and blue light protection. The crystalline lens of the eye filters these potentially harmful rays and many premium IOLs are designed to undertake this task as well. According to a few studies though, these lenses have been associated with a decrease in vision quality.

Another type of intraocular lens is the light-adjustable one which is still undergoing FDA clinical trials. This particular type of IOL is implanted in the eye and then treated with light of a certain wavelength in order to alter the curvature of the lens.

In some cases, surgeons may opt for inserting an additional lens over the already implanted one. This type of IOLs procedures are called "piggyback" IOLs and are usually considered an option whenever the lens result of the first implant is not optimal. In such cases, implanting another IOL over the existent one is considered safer than replacing the initial lens. This approach may also be used in patients who need high degrees of vision correction.

No matter which IOL is used, the surgeon will need to select the appropriate power of IOL (much like an eyeglass prescription) to provide the patient with the desired refractive outcome. Traditionally, doctors use preoperative measurements including corneal curvature, axial length, and white to white measurements to estimate the required power of the IOL. These traditional methods include several formulas including Hagis, Hoffer Q, Holladay 1, Holladay 2, and SRK/T, to name a few. Refractive results using traditional power calculation formulas leave patients within 0.5D of target (correlates to 20/25 when targeted for distance) or better in 55% of cases and within 1D (correlates to 20/40 when targeted for distance) or better in 85% of cases. Recent developments in interoperative wavefront technology such as the ORA System from Wavetec Vision Systems, have demonstrated in studies, power calculations that provide improved outcomes, yielding 80% of patients within 0.5D (20/25 or better).

Statistically, cataract surgery and IOL implantation seem to be procedures with the safest and highest success rates when it comes to eye care. However, as with any other type of surgery, it implies certain risks. The cost is another important aspect of these lenses. Although most insurance companies cover the costs of traditional IOLs, patients may need to pay the price difference if they choose the more expensive premium ones.

Preoperative evaluation

An eye examination or pre-operative evaluation by an eye surgeon is necessary to confirm the presence of a cataract and to determine if the patient is a suitable candidate for surgery. The patient must fulfill certain requirements such as:

- The degree of reduction of vision due, at least in large part, to the cataract should be evaluated. While the existence of other sight-threatening diseases, such as age-related macular degeneration or glaucoma, does not preclude cataract surgery, less improvement may be expected in their presence.

- The eyes should have a normal pressure, or any pre-existing glaucoma should be adequately controlled with medications. In cases of uncontrolled glaucoma, a combined cataract-glaucoma procedure (phaco-trabeculectomy) can be planned and performed.

- The pupil should be adequately dilated using eyedrops; if pharmacologic pupil dilation is inadequate, procedures for mechanical pupillary dilatation may be needed during the surgery.

- The patients with retinal detachment may be scheduled for a combined vitreo-retinal procedure, along with PC-IOL implantation.

- In addition, it has recently been shown that patients taking tamsulosin (Flomax), a common drug for enlarged prostate, are prone to developing a surgical complication known as intraoperative floppy iris syndrome (IFIS), which must be correctly managed to avoid the complication posterior capsule rupture; however, prospective studies have shown that the risk is greatly reduced if the surgeon is informed of the patient's history with the drug beforehand, and has appropriate alternative techniques prepared.[13]

- A Cochrane Review of three randomized clinical trials including over 21,500 cataract surgeries examined whether routine preoperative medical testing resulted in a reduction of adverse events during surgery. Results showed that performing preoperative medical testing did not result in a reduction of risk of intraoperative or postoperative medical adverse events, compared to surgeries with no or limited preoperative testing.[14]

Operation procedures

The surgical procedure in phacoemulsification for removal of cataract involves a number of steps, and is typically performed under an operating microscope. Each step must be carefully and skillfully performed in order to achieve the desired result. The steps may be described as follows:

- Anaesthesia; Topical anesthetic agents are most commonly used and may be placed on the globe prior to surgery and or in the globe during surgery.[15] Anesthetic injection techniques include sub-conjunctival injections and or injections posterior to the globe (retrobulbar block) to produce a regional nerve block. Intravenous sedation may be combined with the topical and injection techniques. General anesthesia with the patient unconscious from intravenous agents and or inhaled gases is another technique, however general anaesthetic is not the standard treatment.

- Exposure of the eyeball using an eyelid speculum;

- Entry into the eye through a minimal incision (corneal or scleral);

- Viscoelastic This is injected to stabilize the anterior chamber, to help maintain eye pressurization, and to distend the cataract's capsule during IOL implantation.

- Capsulorhexis; This step involves making a circular opening on the front surface of the lens in order to access the cloudy lens material within.

- Hydrodissection; The cataract's outer cortical layer is dissected, by the injection of a fluid wave, from the capsule, the outer-most skin of the cataract.

- Hydrodelineation; The cataract's outer softer epi-nucleus is separated from the inner firmer endo-nucleus by the injection of a fluid wave. The epi-nucleus serves to protect the cataract's capsule during phacoemulsification of the endo-nucleus.

- Ultrasonic destruction or emulsification of the cataract after nuclear cracking or chopping (if needed), careful aspiration of the remaining lens cortex (outer layer of lens) material from the capsular bag, capsular polishing (if needed);

- Implantation of the, usually foldable, intraocular lens (IOL);

- Viscoelastic removal; The viscoelastic injected to stabilize the anterior chamber, protect the cornea from damage, and distend the cataract's capsule during IOL implantation must be removed from the eye to prevent viscoelastic glaucoma (a severe intra-ocular pressure increase) post-operatively. This is done via suction from the irrigation-aspiration instrument.

- Wound sealing / hydration (if needed). The incision is sealed by elevating the pressure inside the globe which presses the internal tissue against the external tissue of the incision forcing closed the incision.

The pupil is dilated using drops (if the IOL is to be placed behind the iris) to help better visualise the cataract. Pupil-constricting drops are reserved for secondary implantation of the IOL in front of the iris (if the cataract has already been removed without primary IOL implantation). Anesthesia may be placed topically (eyedrops) or via injection next to (peribulbar) or behind (retrobulbar) the eye.[15] Topical anaesthetics are commonly used at the same time as a intracameral lidocaine injection to reduce pain during the operation.[15] Oral or intravenous sedation may also be used to reduce anxiety. General anesthesia is rarely necessary, but may be employed for children and adults with particular medical or psychiatric issues.[15] The operation may occur on a stretcher or a reclining examination chair. The eyelids and surrounding skin will be swabbed with disinfectant. The face is covered with a cloth or sheet, with an opening for the operative eye. The eyelid is held open with a speculum to minimize blinking during surgery. Pain is usually minimal in properly anesthetised eyes, though a pressure sensation and discomfort from the bright operating microscope light is common. The ocular surface is kept moist using sterile saline eye drops or methylcellulose viscoelastic. The discission into the lens of the eye is performed at or near where the cornea and sclera meet (limbus = corneoscleral junction). Advantages of the smaller incision include use of few or no stitches and shortened recovery time.[5][16]

A capsulotomy (rarely known as cystotomy) is a procedure to open a portion of the lens capsule, using an instrument called a cystotome.[17] An anterior capsulotomy refers to the opening of the front portion of the lens capsule, whereas a posterior capsulotomy refers to the opening of the back portion of the lens capsule. In phacoemulsification, the surgeon performs an anterior continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis, to create a round and smooth opening through which the lens nucleus can be emulsified and the intraocular lens implant inserted.

Following cataract removal (via ECCE or phacoemulsification, as described above), an intraocular lens is usually inserted. After the IOL is inserted, the surgeon checks that the incision does not leak fluid. This is a very important step, since wound leakage increases the risk of unwanted microorganisms gaining access into the eye and predisposing it to endophathalmitis. An antibiotic/steroid combination eye drop is put in and an eye shield may be applied on the operated eye, sometimes supplemented with an eye patch.

Antibiotics may be administered pre-operatively, intra-operatively, and/or post-operatively. Frequently a topical corticosteroid is used in combination with topical antibiotics post-operatively.

Most cataract operations are performed under a local anaesthetic, allowing the patient to go home the same day. The use of an eye patch may be indicated, usually for about some hours, after which the patient is instructed to start using the eyedrops to control the inflammation and the antibiotics that prevent infection. Lens and cataract procedures are commonly performed in an outpatient setting; in the United States, 99.9% of lens and cataract procedures were done in an ambulatory setting in 2012.[18]

Occasionally, a peripheral iridectomy may be performed to minimize the risk of pupillary block glaucoma. An opening through the iris can be fashioned manually (surgical iridectomy) or with a laser (called Nd-YAG laser iridotomy). The laser peripheral iridotomy may be performed either prior to or following cataract surgery.

The iridectomy hole is larger when done manually than when performed with a laser. When the manual surgical procedure is performed, some negative side-effects may occur, such as that the opening of the iris can be seen by others (aesthetics), and the light can fall into the eye through the new hole, creating some visual disturbances. In the case of visual disturbances, the eye and brain often learn to compensate and ignore the disturbances over a couple of months. Sometimes the peripheral iris opening can heal, which means that the hole ceases to exist. This is the reason that the surgeon sometimes makes two holes, so that at least one hole is kept open.

After the surgery, the patient is instructed to use anti-inflammatory and antibiotic eye-drops for up to two weeks (depending on the inflammation status of the eye and some other variables). The eye surgeon will judge, based on each patient's idiosyncrasies, the time length to use the eye drops. The eye will be mostly recovered within a week, and complete recovery should be expected in about a month. The patient should not participate in contact/extreme sports until cleared to do so by the eye surgeon.

Complications

Complications after cataract surgery are relatively uncommon.

- PVD – Posterior vitreous detachment does not directly threaten vision. Even so, it is of increasing interest because the interaction between the vitreous body and the retina might play a decisive role in the development of major pathologic vitreoretinal conditions. PVD may be more problematic with younger patients, since many patients older than 60 have already gone through PVD. PVD may be accompanied by peripheral light flashes and increasing numbers of floaters.

- PCO – Some people can develop a posterior capsular opacification (PCO), also called an after-cataract. As a physiological change expected after cataract surgery, the posterior capsular cells undergo hyperplasia and cellular migration, showing up as a thickening, opacification and clouding of the posterior lens capsule (which is left behind when the cataract was removed, for placement of the IOL). This may compromise visual acuity and the ophthalmologist can use a device to correct this situation. It can be safely and painlessly corrected using a laser device to make small holes in the posterior lens capsule of the crystalline. It usually is a quick outpatient procedure that uses a Nd-YAG laser (neodymium-yttrium-aluminum-garnet) to disrupt and clear the central portion of the opacified posterior pole of the capsule (posterior capsulotomy).[19] This creates a clear central visual axis for improving visual acuity.[20] In very thick opacified posterior capsules, a surgical (manual) capsulectomy is the surgical procedure performed. A YAG capsulotomy is, however, a factor which must be taken in consideration in the event of IOL replacement as vitreous can migrate toward the anterior chamber through the opening hitherto occluded by the IOL.

- Posterior capsular tear may be a complication during cataract surgery. The rate of posterior capsular tear among skilled surgeons is around 2% to 5%. It refers to a rupture of the posterior capsule of the natural lens. Surgical management may involve anterior vitrectomy and, occasionally, alternative planning for implanting the intraocular lens, either in the ciliary sulcus, in the anterior chamber (in front of the iris), or, less commonly, sutured to the sclera.

- Retinal detachment normally occurs at a prevalence of 1 in 1,000 (0.1%), but patients who have had cataract surgery are at an increased risk (0.5–0.6%) of developing rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RRD) – the most common form of retinal detachment.[21] Cataract surgery speeds up the rate of vitreous humor liquefaction and this leads to increased rates of RRD.[22] When a retinal tear occurs, vitreous liquid enters the space between the retina and retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE) and presents as flashes of light (photopsia), dark floaters, and loss of peripheral vision.[21]

- Toxic anterior segment syndrome or TASS is a non-infectious inflammatory condition that may occur following cataract surgery. It is usually treated with topical corticosteroids in high dosage and frequency.

- Endophthalmitis is a serious infection of the intraocular tissues, usually following intraocular surgery, or penetrating trauma. There is some concern that the clear cornea incision might predispose to the increase of endophthalmitis but there is no conclusive study to corroborate this suspicion.[23] An intracameral injection of antibiotics may be used as a preventive measure.

- Glaucoma may occur and it may be very difficult to control. It is usually associated with inflammation, especially when little fragments or chunks of the nucleus get access to the vitreous cavity. Some experts recommend early intervention when this condition occurs (posterior pars plana vitrectomy). Neovascular glaucoma may occur, especially in diabetic patients. In some patients, the intraocular pressure may remain so high that blindness may ensue.

- Swelling or edema of the central part of the retina, called macula, resulting in macular edema, can occur a few days or weeks after surgery. Most such cases can be successfully treated. Preventative use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs has been reported to reduce the risk of macular edema to some extent.[24]

- Uveitis–Glaucoma–Hyphema syndrome: This is a complication of cataract surgery caused due to the mechanical irritation of mispositioned intraocular lens over iris, ciliary body or iridocorneal angle.[25]

- Other possible complications include: Swelling or edema of the cornea, sometimes associated with cloudy vision, which may be transient or permanent (pseudophakic bullous keratopathy). Displacement or dislocation of the intraocular lens implant may rarely occur. Unplanned high refractive error (either myopic or hypermetropic) may occur due to error in the ultrasonic biometry (measure of the length and the required intraocular lens power). Cyanopsia, in which the patient sees everything tinted with blue, often occurs for a few days, weeks or months after removal of a cataract. Floaters commonly appear after surgery.

History

Ancient Babylonia

Cataract surgery was first mentioned in the Babylonian code of Hammurabi 1750 BCE.[26]

Ancient Egypt

Possibly the first depiction of cataract surgery in recorded history is on a statue from the Fifth Dynasty (2467–2457 BCE).[27] It is further alleged that a "relief painting from tomb number TT 217 in a worker settlement in Deir-el-Medina" shows "the man buried in the tomb, Ipuy,... one of the builders of royal tombs in the renowned Valley of the Kings, circa 1279–1213 BC"[28] as he underwent cataract surgery.[27]

Ancient Greece and Rome

Galen of Pergamon 2nd century CE, a prominent Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher, performed an operation similar to modern cataract surgery. Using a needle-shaped instrument, Galen attempted to remove a cataract-affected lens.[29][30] Although many 20th century historians have claimed that Galen believed the lens to be in the exact center of the eye, Galen actually understood that the crystalline lens is located in the anterior aspect of the human eye.[31]

India

A form of cataract surgery, now known as "couching", was found in ancient India and subsequently introduced to other countries by the Indian physician Sushruta (c. 6th century BCE),[32] who described it in his work the Compendium of Sushruta or Sushruta Samhita. The Uttaratantra section of the Compendium, chapter 17, verses 55–69, describes an operation in which a curved needle was used to push the opaque phlegmatic matter (kapha in Sanskrit) in the eye out of the way of vision. The phlegm was then blown out of the nose. The eye would later be soaked with warm clarified butter and then bandaged. Here is translation from the original Sanskrit:

vv. 55–56: Now procedure of surgical operation of ślaiṣmika liṅganāśa (cataract) will be described. It should be taken up (for treatment) if the diseased portion in the pupillary region is not shaped like half moon, sweat drop or pearl: not fixed, uneven and thin in the centre, streaked or variegated and is not found painful or reddish.

vv. 57–61ab: In moderate season, after unction and sudation, the patient should be positioned and held firmly while gazing at his nose steadily. Now the wise surgeon leaving two parts of white circle from the black one towards the outer canthus should open his eyes properly free from vascular network and then with a barley-tipped rod-like instrument held firmly in hand with middle, index and thumb fingers should puncture the natural hole-like point with effort and confidence not below, above or in sides. The left eye should be punctured with right hand and vice-versa. When punctured properly a drop of fluid comes out and alsoe there is some typical sound.

vv. 61bc–64ab: Just after puncturing, the expert should irrigate the eye with breast-milk and foment it from outside with vāta-[wind-]alleviating tender leaves, irrespective of doṣa [defect] being stable or mobile, holding the instrument properly in position. Then the pupillary circle should be scraped with the tip of the instrument while the patient, closing the nostril of the side opposite to the punctured eye, should blow so that kapha [phlegm] located in the region be eliminated.

vv. 64cd–67: When pupillary region becomes clear like cloudless sun and is painless, it should be considered as scraped properly. (If doṣa [defect] cannot be eliminated or it reappears, puncturing is repeated after unction and sudation.) When the sights are seen properly the śalākā [probe] should be removed slowly, eye anointed with ghee and bandaged. Then the patient :should lie down in supine position in a peaceful chamber. He should avoid belching, coughing, sneezing, spitting and shaking during the operation and thereafter should observe the restrictions as after intake of sneha [oil].

v. 68: Eye should be washed with vāta-[wind-]alleviating decoctions after every three days and to eliminate fear of (aggravation of) vāyu [wind], it should also be fomented as mentioned before (from outside and mildly).

v. 69: After observing restrictions for ten days in this way, post-operative measures to normalise vision should be employed along with light diet in proper quantity.[33]

The removal of cataracts by surgery was also introduced into China from India, and flourished in the Sui (581–618 CE) and Tang dynasties (618–907 CE).[34]

West Africa

The removal of cataracts was a common surgical procedure in Djenné[35](as in many other parts of Africa[36]).

Europe and the Islamic world

The first references to cataract and its treatment in Europe are found in 29 AD in De Medicinae, the work of the Latin encyclopedist Aulus Cornelius Celsus, which also describes a couching operation.

Couching continued to be used throughout the Middle Ages and is still used in some parts of Africa and in Yemen.[37] However, couching is an ineffective and dangerous method of cataract therapy, and often results in patients remaining blind or with only partially restored vision.[37] For the most part, it has now been replaced by extracapsular cataract surgery and, especially, phacoemulsification.[38]

The lens can also be removed by suction through a hollow instrument. Bronze oral suction instruments have been unearthed that seem to have been used for this method of cataract extraction during the 2nd century CE.[39] Such a procedure was described by the 10th-century Persian physician Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi, who attributed it to Antyllus, a 2nd-century Greek physician. The procedure "required a large incision in the eye, a hollow needle, and an assistant with an extraordinary lung capacity".[40] This suction procedure was also described by the Iraqi ophthalmologist Ammar Al-Mawsili, in his Choice of Eye Diseases, also written in the 10th century.[40] He presented case histories of its use, claiming to have had success with it on a number of patients.[40] Extracting the lens has the benefit of removing the possibility of the lens migrating back into the field of vision.[41] A later variant of the cataract needle in 14th-century Egypt, reported by the oculist Al-Shadhili, used a screw to produce suction. It is not clear, however, how often this method was used as other writers, including Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi and Al-Shadhili, showed a lack of experience with this procedure or claimed it was ineffective.[40]

Eighteenth century and later

In 1748, Jacques Daviel was the first modern European physician to successfully extract cataracts from the eye. In America, an early form of surgery known as cataract couching may have been performed in 1611,[42] and cataract extraction was most likely performed by 1776.[43] Cataract extraction by aspiration of lens material through a tube to which suction is applied was performed by Philadelphia surgeon Philip Syng Physick in 1815.[44]

King Serfoji II Bhonsle of Thanjavur in India performed cataract surgeries as documented in manuscripts at the Saraswathi Mahal Library in the early 1800s.

In 1949, Harold Ridley introduced the concept of implantation of the intraocular lens which permitted more efficient and comfortable visual rehabilitation possible after cataract surgery.[45]

In 1967, Charles Kelman introduced phacoemulsification, a technique that uses ultrasonic waves to emulsify the nucleus of the crystalline lens in order to remove the cataracts without a large incision. This new method of surgery decreased the need for an extended hospital stay and made the surgery ambulatory. Patients who undergo cataract surgery hardly complain of pain or even discomfort during the procedure. However patients who have topical anesthesia, rather than peribulbar block anesthesia, may experience some discomfort.[46]

According to surveys of members of the American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery, approximately 2.85 million cataract procedures were performed in the United States during 2004 and 2.79 million in 2005.[47]

In India, modern surgery with intraocular lens insertion in government- and NGO-sponsored Eye Surgical camps has replaced older surgical procedures. In rare cases, infections have caused blindness among some of the patients in mass free eye camps in India.[48]

Usage in the United Kingdom

In the UK the practice of the various National Health Service healthcare providers in referring people with cataracts to surgery varied widely as of 2017, with many of the providers only referring people with moderate or severe vision loss, and often with delays.[49] This is despite guidance issued by the NHS executive in 2000 urging providers to standardize care, streamline the process, and increase the number of cataract surgeries performed in order to meet the needs of the aging population.[50] The national ophthalmology outcomes audit in 2019 found five NHS trusts with complication rates between 1.5% and 2.1%, but since the first national cataract audit in 2010, there had been a 38% reduction in posterior capsule rupture complications.[51]

See also

- Africa Cataract Project

- Eye surgery

- Himalayan Cataract Project

- Ophthalmology

References

- "Cataracts | National Eye Institute". www.nei.nih.gov. Retrieved 2020-07-27.

- "Cataract surgery". Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- Lawrence D, Fedorowicz Z, van Zuuren EJ, et al. (Cochrane Eyes and Vision Group) (November 2015). "Day care versus in-patient surgery for age-related cataract". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (11): CD004242. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004242.pub5. PMC 7197209. PMID 26524611.

- Haldipurkar, S S; Shikari, Hasanain T; Gokhale, Vishwanath (2009). "Wound construction in manual small incision cataract surgery". Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 57 (1): 9–13. ISSN 0301-4738. PMC 2661512. PMID 19075401.

- Extracapsular Cataract Extraction – Definition, Purpose, Demographics, Description, Diagnosis/preparation, Aftercare, Risks, Normal results, Morbidity and mortality rates, Alternatives Encyclopedia of Surgery: A Guide for Patients and Caregivers

- Alió JL, Abdou AA, Puente AA, Zato MA, Nagy Z (June 2014). "Femtosecond laser cataract surgery: updates on technologies and outcomes". Journal of Refractive Surgery. 30 (6): 420–427. doi:10.3928/1081597x-20140516-01. PMID 24972409.

- Popovic M, Campos-Möller X, Schlenker MB, Ahmed II (October 2016). "Efficacy and Safety of Femtosecond Laser-Assisted Cataract Surgery Compared with Manual Cataract Surgery: A Meta-Analysis of 14 567 Eyes". Ophthalmology. 123 (10): 2113–2126. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.07.005. PMID 27538796.

- "Cryotherapy for cataracts". Encyclopedia of Surgery

- Meadow, Norman B. "Cryotherapy: A fall from grace, but not a crash". Ophthalmology Times. October 15, 2005.

- New Device Approval – CrystaLens Model AT-45 Accommodating IOL – P030002. U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

- Singh, Vivek Mahendrapratap; Ramappa, Muralidhar; Murthy, Somasheila I; Rostov, Audrey Talley (January 2022). "Toric intraocular lenses: Expanding indications and preoperative and surgical considerations to improve outcomes". Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 70 (1): 10–23. doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO_1785_21. ISSN 0301-4738. PMC 8917572. PMID 34937203.

- Ramappa, Muralidhar; Singh, VivekMahendrapratap; Murthy, SomasheilaI; Rostov, AudreyTalley (2022). "Toric intraocular lenses: Expanding indications and preoperative and surgical considerations to improve outcomes". Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 70 (1): 10. doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO_1785_21. ISSN 0301-4738.

- Charters, Linda Anticipation is key to managing intra-operative floppy iris syndrome Archived 2006-10-22 at the Wayback Machine. Ophthalmology Times. June 15, 2006.

- Keay L, Lindsley K, Tielsch J, Katz J, Schein O (January 2019). "Routine preoperative medical testing for cataract surgery". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1: CD007293. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007293.pub4. PMC 6353242. PMID 30616299.

- Minakaran N, Ezra DG, Allan BD (July 2020). "Topical anaesthesia plus intracameral lidocaine versus topical anaesthesia alone for phacoemulsification cataract surgery in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 7: CD005276. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd005276.pub4. PMC 8190979. PMID 35658539.

- Surgery Encyclopedia – Phacoemulsification for cataracts

- Capsulorhexis using a cystotome needle during cataract surgery Archived 2008-08-26 at the Wayback Machine

- Wier LM, Steiner CA, Owens PL (February 2015). "Surgeries in Hospital-Owned Outpatient Facilities, 2012". HCUP Statistical Brief #188. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- "Videos: YAG Laser Capsulotomy". Pacific Cataract and Laser Institute. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- Surgery Encyclopedia – Laser posterior capsulotomy

- Steel D (March 2014). "Retinal detachment". BMJ Clinical Evidence. 2014. PMC 3940167. PMID 24807890.

- Feltgen N, Walter P (January 2014). "Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment--an ophthalmologic emergency". Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 111 (1–2): 12–21, quiz 22. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2014.0012. PMC 3948016. PMID 24565273.

- "Endophthalmitis". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- Lim BX, Lim CH, Lim DK, Evans JR, Bunce C, Wormald R (November 2016). "Prophylactic non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the prevention of macular oedema after cataract surgery". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11: CD006683. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006683.pub3. PMC 6464900. PMID 27801522.

- Zemba M, Camburu G (2017). "Uveitis-Glaucoma-Hyphaema Syndrome. General review". Romanian Journal of Ophthalmology. 61 (1): 11–17. doi:10.22336/rjo.2017.3. PMC 5710046. PMID 29450365.

- Ascaso FJ, Lizana J, Cristóbal JA (March 2009). "Cataract surgery in ancient Egypt". Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery. 35 (3): 607–608. doi:10.1016/j.jcrs.2008.11.052. PMID 19251160.

- Ascaso FJ, Lizana J, Cristóbal JA (March 2009). "Cataract surgery in ancient Egypt". Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery. 35 (3): 607–608. doi:10.1016/j.jcrs.2008.11.052. PMID 19251160.

- "Hoax: Picture from Ancient Egypt Nothing to Do with COVID-19 Test". TASR. 25 January 2021.

- Urabe H (September 1976). "[Classification of ringworm infections (author's transl)]". Nihon Hifuka Gakkai Zasshi. The Japanese Journal of Dermatology. 86 (10): 573–581. PMID 1034789.

- Magner LN (1992). A History of Medicine. CRC Press. p. 91.

- Leffler CT, Hadi TM, Udupa A, Schwartz SG, Schwartz D (2016). "A medieval fallacy: the crystalline lens in the center of the eye". Clinical Ophthalmology. 10 (10): 649–662. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S100708. PMC 4833360. PMID 27114699.

- Meulenbeld GJ (1999–2002). A History of Indian Medical Literature. Groningen: Forsten.

- Sharma PV (2001). Suśruta-Saṃhitā with English translation of text and Ḍalhaṇa's commentary along with critical notes. Vol ĪI (Kalpasthāna and Uttaratantra). Varanasi, India: Chaukhambha Visvabharati Oriental. pp. 202–204.

- Deshpande V (2000). "Ophthalmic surgery: a chapter in the history of Sino-Indian medical contacts". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 63 (3): 370–388. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00008454. S2CID 162655091. See also Deshpande V (1999). "Indian influences on early Chinese ophthalmology: glaucoma as a case study". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 62 (22): 306–322. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00016724.

- McKissack P, McKissack F (1995). The Royal Kingdoms of Ghana, Mali, and Songhay Life in Medieval Africa. Macmillan. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-8050-4259-7.

- Thompson EE (January 1965). "PRIMITIVE AFRICAN MEDICAL LORE AND WITCHCRAFT". Bulletin of the Medical Library Association. 53: 80–94. PMC 198231. PMID 14223742.

- 'Couching' for cataracts remains a persistent problem in Yemen Archived 2011-07-26 at the Wayback Machine, EuroTimes, September 2005, p. 11.

- "Toric Lens Implants | Pacific Cataract and Laser Institute: For Doctors of Optometry". odpcli.com. Retrieved 2019-10-09.

- Bergman WC, Schulz RA, Davis DS (September 2009). "Factors influencing the genesis of neurosurgical technology". Neurosurgical Focus. 27 (3): E3. doi:10.3171/2009.6.FOCUS09117. PMID 19722817..

- Savage-Smith E (August 2000). "The practice of surgery in Islamic lands: myth and reality". Social History of Medicine. 13 (2): 307–321. doi:10.1093/shm/13.2.307. PMID 14535259.

- Finger S (1994). Origins of Neuroscience: A History of Explorations Into Brain Function. Oxford University Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-19-514694-3.

- Leffler CT, Wainsztein RD (2016). "The first cataract surgeons in Latin America: 1611-1830". Clinical Ophthalmology. 10: 679–694. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S105825. PMC 4841434. PMID 27143845.

- Leffler CT, Schwartz SG, Grzybowski A, Braich PS (2015). "The first cataract surgeons in Anglo-America". Survey of Ophthalmology. 60 (1): 86–92. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2014.08.002. PMC 4262555. PMID 25444521.

- Leffler CT, Letocha CE, Pierson K, Schwartz SG (2017). "Aspiration of cataract in 1815 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania". Digital Journal of Ophthalmology. 23 (4): 4–7. doi:10.5693/djo.01.2017.10.001. PMC 5791631. PMID 29403333.

- Davis G (January 2016). "The Evolution of Cataract Surgery". Missouri Medicine. Missouri State Medical Association. 113 (1): 58–62. PMC 6139750. PMID 27039493.

- Pandey, Suresh K.; Milverton, E. John; Maloof, Anthony J. (October 2004). "A tribute to Charles David Kelman MD: ophthalmologist, inventor and pioneer of phacoemulsification surgery". Clinical & Experimental Ophthalmology. 32 (5): 529–533. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9071.2004.00887.x. ISSN 1442-6404. PMID 15498067.

- American Academy of Ophthalmology reference

- "India cataracts scandal: Arrests over 'botched' surgery". BBC. 5 December 2014.

- "Two thirds of eye units restricting access to cataract surgery". OnMedica. 10 November 2017. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- "Action on Cataracts Good Practice Guidance" (PDF). NHS Executive via the Royal College of Ophthalmologists. January 2000., referenced in "Context: Guideline for Cataracts in adults". NICE. October 2017.

- "Revealed: The trusts with the highest cataract complication rates". Health Service Journal. 11 October 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

Further reading

- Frampton G, Harris P, Cooper K, Lotery A, Shepherd J (November 2014). "The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of second-eye cataract surgery: a systematic review and economic evaluation". Health Technology Assessment. NIHR Journals Library. 18 (68): 1–205, v–vi. doi:10.3310/hta18680. PMC 4781176. PMID 25405576. 18.68.

- Prajna NV, Ravilla TD, Srinivasan S (2015). "Ch: 11. Cataract Surgery". In Debas HT, Donkor P, Gawande A, Jamison DT, Kruk ME, Mock CN (eds.). Essential Surgery. Disease Control Priorities. Vol. 1 (3rd ed.). The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. ISBN 978-1-4648-0346-8.

External links

- Cataract Surgery – slideshow by The New York Times