Childhood trauma

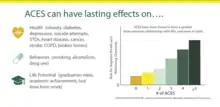

Childhood trauma is often described as serious adverse childhood experiences (ACEs).[1] Children may go through a range of experiences that classify as psychological trauma; these might include neglect,[2] abandonment,[2] sexual abuse, emotional abuse, and physical abuse,[2] witnessing abuse of a sibling or parent, or having a mentally ill parent. These events have profound psychological, physiological, and sociological impacts and can have negative, lasting effects on health and well-being such as unsocial behaviors, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and sleep disturbances.[3] Similarly, children with mothers who have experienced traumatic or stressful events during pregnancy can increase the child's risk of mental health disorders and other neurodevelopmental disorders.[3] Kaiser Permanente and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's 1998 study on adverse childhood experiences determined that traumatic experiences during childhood are a root cause of many social, emotional, and cognitive impairments that lead to increased risk of unhealthy self-destructive behaviors,[2] risk of violence or re-victimization, chronic health conditions, low life potential and premature mortality. As the number of adverse experiences increases, the risk of problems from childhood through adulthood also rises.[4] Nearly 30 years of study following the initial study has confirmed this. Many states, health providers, and other groups now routinely screen parents and children for ACEs.

Health

Traumatic experiences during childhood causes stress that increases an individual's allostatic load and thus affects the immune system, nervous system, and endocrine system.[5][6][7][8] Exposure to chronic stress triples or quadruples the vulnerability to adverse medical outcomes.[9] Childhood trauma is often associated with adverse health outcomes including depression, hypertension, autoimmune diseases, lung cancer, and premature mortality.[5][7][10][11] Effects of childhood trauma on brain development includes a negative impact on emotional regulation and impairment of development of social skills.[7] Research has shown that children raised in traumatic or risky family environments tend to have excessive internalizing (e.g., social withdrawal, anxiety) or externalizing (e.g., aggressive behavior), and suicidal behavior.[7][12][13] Recent research has found that physical and sexual abuse are associated with mood and anxiety disorders in adulthood, while personality disorders and schizophrenia are linked with emotional abuse as adults.[14][15] In addition, research has proposed that mental health outcomes from childhood trauma may be better understood through a dimensional framework (internalizing and externalizing) as opposed to specific disorders.[16]

Psychological impact

Childhood trauma can increase the risk of mental disorders including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), attachment issues, depression, and substance abuse. Sensitive and critical stages of child development can result in altered neurological functioning, adaptive to a malevolent environment but difficult for more benign environments.

In a study done by Stefania Tognin and Maria Calem comparing healthy comparisons (HC) and individuals at clinically high risk for developing psychosis (CHR), 65.6% CHR patients and 23.1% HC experienced some level of childhood trauma. The conclusion of the study shows that there is a correlation between the effects of childhood trauma and the being at high risk for psychosis.[17]

Effects on adults

As an adult feelings of anxiety, worry, shame, guilt, helplessness, hopelessness, grief, sadness and anger that started with a trauma in childhood can continue. In addition, those who endure trauma as a child are more likely to encounter anxiety, depression, suicide and self harm, PTSD, drug and alcohol misuse and relationship difficulties.[18] The effects of childhood trauma don't end with just emotional repercussions. Survivors of childhood trauma are also at higher risk of developing asthma, coronary heart disease, diabetes or having a stroke. They are also more likely to develop a "heightened stress response" which can make it difficult for them to regulate their emotions, lead to sleep difficulties, lower immune function, and increase the risk of a number of physical illnesses throughout adulthood.[18]

Epigenetics

Childhood trauma [8] can leave epigenetic marks on a child's genes, which chemically modify gene expression by silencing or activating genes.[19] This can alter fundamental biological processes and adversely affect health outcomes throughout life.[19] A 2013 study found that people who had experienced childhood trauma had different neuropathology than people with PTSD from trauma experienced after childhood.[19] Another recent study in rhesus macaques showed that DNA methylation changes related to early-life adversity persisted into adulthood.[20]

Survivors of war trauma or childhood maltreatment are at increased risk for trauma-spectrum disorders[21] such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In addition, traumatic stress has been associated with alterations in the neuroendocrine and the immune system, enhancing the risk for physical diseases.[22] In particular, epigenetic alterations in genes regulating the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis as well as the immune system have been observed in survivors of childhood and adult trauma.[23][24]

Traumatic experiences might even affect psychological as well as biological parameters in the next generation, i.e. traumatic stress might have trans generational effects.[25][21] Parental trauma exposure was found to be associated with greater risk for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and mood and anxiety disorders in offspring since biological alterations associated with PTSD and/or other stress-related disorders have also been observed in offspring of trauma survivors who do not themselves report trauma exposure or psychiatric disorder.[26] Animal models have demonstrated that stress exposure can result in epigenetic alterations in the next generation, and such mechanisms have been hypothesized to underpin vulnerability to symptoms in offspring of trauma survivors.[27] Enduring behavioral responses to stress and epigenetic alterations in adult offspring have been demonstrated to be mediated by changes in gametes in utero effects, variations in early postnatal care, and/or other early life experiences that are influenced by parental exposure (Yehuda, Daskalakis, Bierer, Bader, Klengel, Holsboer, and Binder, 2015).

These changes could result in enduring alterations of the stress response as well as the physical health risk.[21] Furthermore, the effects of parental trauma could be transmitted to the next generation by parental distress and the pre- and postnatal environment, as well as by epigenetic marks transmitted via the germline.[26] While epigenetic research has a high potential of advancing our understanding of the consequences of trauma, the findings have to be interpreted with caution, as epigenetics only represent one piece of a complex puzzle of interacting biological and environmental factors.[21]

See also

- Center for Child and Family Health, founded 1996

References

- Zhao R. "Child Abuse Leaves Epigenetic Marks". National Human Genome Research Institute.[?]

Socioeconomic costs

The social and economic costs of child abuse and neglect are difficult to calculate. Some costs are straightforward and directly related to maltreatment, such as hospital costs for medical treatment of injuries sustained as a result of physical abuse and foster care costs resulting from the removal of children when they cannot remain safely with their families. Other costs, less directly tied to the incidence of abuse, include lower academic achievement, adult criminality, and lifelong mental health problems. Both direct and indirect costs impact society and the economy.[28][29]

Transgenerational effects

People can pass their epigenetic marks including de-myelinated neurons to their children. The effects of trauma can be transferred from one generation of childhood trauma survivors to subsequent generations of offspring. This is known as transgenerational trauma or intergenerational trauma, and can manifest in parenting behaviors as well as epigenetically.[30][31][32] Exposure to childhood trauma, along with environmental stress, can also cause alterations in genes and gene expressions.[33][34][35] A growing body of literature suggests that children's experiences of trauma and abuse within close relationships not only jeopardize their well-being in childhood, but can also have long-lasting consequences that extend well into adulthood.[36] These long-lasting consequences can include emotion regulation issues, which can then be passed onto subsequent generations through child-parent interactions and learned behaviors.[37] (see also behavioral epigenetics, epigenetics, historical trauma, and cycle of violence)

Resilience

Exposure to maltreatment in childhood significantly predicts a variety of negative outcomes in adulthood.[38] However, not all children who are exposed to a potentially traumatic event develop subsequent struggles with mental or physical health.[39] Therefore, there are factors that reduce the impact of potentially traumatic events and protect an individual from developing mental health problems after exposure to a potentially traumatic event. These are called resiliency factors.

Research regarding children who showed adaptive development while facing adversity began in the 1970s and continues to this day.[40] Resilience is defined as “the process of, capacity for, or outcome of successful adaptation despite challenging or threatening circumstances."[41] The concept of resilience stems from research that showed experiencing positive emotions had a restorative and preventive effect on the experience of negative emotions more broadly with regards to physical and psychological wellbeing in general and more specifically with reactions to trauma.[42][43] This line of research has contributed to the development of interventions that focus on promoting resilience as opposed to focusing on deficits in an individual who has experienced a traumatic event.[40] Resilience has been found to decrease risk of suicide, depression, anxiety and other mental health struggles associated with exposure to trauma in childhood.[44][45][46][47]

When an individual who is high in resilience experiences a potentially traumatic event, their relative level of functioning does not significantly deviate from the level of functioning they exhibited prior to exposure to a potentially traumatic event.[41] Furthermore, that same individual may recover more quickly and successfully from a potentially traumatic experience than an individual who could be said to be less resilient.[41] In children, level of functioning is operationalized as the child continuing to behave in a manner that is considered developmentally appropriate for a child of that age.[40] Level of functioning is also measured by the presence of mental health disorders such as depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, and so on.[39]

Factors that affect resilience

Factors that affect resilience include cultural factors like socioeconomic status, such that having more resources at one's disposal usually equates to more resilience to trauma.[40] Furthermore, the severity and duration of the potentially traumatic experience affect the likelihood of experiencing negative outcomes as a result of childhood trauma.[39][45] One factor that does not affect resilience is gender, with both males and females being equally sensitive to risk and protective factors.[39] Cognitive ability is also not a predictor of resilience.[39]

Attachment has been shown to be one of the most important factors to consider when it comes to evaluating the relative resilience of an individual.[39] Children with secure attachments to an adult with effective coping strategies were most likely to endure adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) in an adaptive manner.[40] Secure attachments throughout the lifespan (including in adolescence and adulthood) appear to be equally important in fostering and maintaining resilience.[39] Secure attachment to one's peers throughout adolescence is a particularly strong predictor of resilience.[39] Within the context of abuse, it is thought that these secure attachments decrease the extent to which children who are abused perceive others as being untrustworthy.[39] In other words, while some children who are abused might begin to view other people as being unsafe and unable to be trusted, children who are able to develop and maintain healthy relationships are less likely to hold these views. Children who experience trauma but also experience healthy attachment with multiple groups of people (in essence, adults, peers, romantic partners, etc.) throughout childhood, adolescence, and adulthood are particularly resilient.[39]

Personality also affects the development (or lack of development) of adult psychopathology as a result of childhood abuse.[39] Individuals who scored low in neuroticism exhibit fewer negative outcomes, such as psychopathology, criminal activity, and poor physical health, after exposure to a potentially traumatic event.[39] Furthermore, individuals with higher scores on openness to experience, conscientiousness, and extraversion have been found to be more resilient to the effects of childhood trauma.[48][49]

Enhancing resilience

One of the most common misconceptions about resilience is that individuals who show resilience are somehow special or extraordinary in some way.[40] Successful adaptation, or resilience, is quite common among children.[40] This is due in part to the naturally adaptive nature of childhood development. Therefore, resilience is enhanced by protecting against factors that might undermine a child's inborn resilience.[40] Studies suggest that resiliency can be enhanced by providing children who have been exposed to trauma with environments in which they feel safe and are able to securely attach to a healthy adult.[50] Therefore, interventions that promote strong parent-child bonds are particularly effective at buffering against the potential negative effects of trauma.[50]

Furthermore, researchers of resilience argue that successful adaptation is not merely a result, rather a developmental process that is ongoing throughout a person's lifetime.[50] Thus, successful promotion of resilience must also be ongoing throughout a person's lifespan.

Prognosis

Trauma affects all children differently (see stress in early childhood). Some children who experience trauma develop significant and long-lasting problems, while others may have minimal symptoms and recover more quickly.[51] Studies have found that despite the broad impacts of trauma, children can and do recover, and that trauma-informed care and interventions produce better outcomes than “treatment as usual”. Trauma-informed care is defined as offering services or support in a way that addresses the special needs of people who have experienced trauma.[52]

Types of trauma

Emotional Abuse

Emotional abuse is often an understated form of trauma that can occur both overtly and covertly. Emotional abuse revolves around a pattern of emotional manipulation, abusive words, isolation, discretization, humiliation and more that tends to have an internalized effect on an individuals self-esteem, ideals, values and reality.[53] Emotional abuse in children is a distinct issue in relation to childhood trauma and the effects it has on children when growing up in an emotionally abusive household or being in relation with emotionally abusive individuals. [54]

Bullying

Bullying is any unprovoked action with the intention of harming, either physically or psychologically, someone who is considered to have less power, either physically or socially. Bullying is a form of harassment that is often repeated and habitual, and can happen in person or online.[55]

Bullying in childhood may inflict harm or distress and educational harm that can affect the later stage of adolescence.[56] Bullying involvement, as victim, bully, bully/victim, or witness, can threaten the well-being of children. Bullying can be a risk factor for the development of an eating disorder, it can impact the functioning of the HPA axis, and it can impact functioning in adulthood. It increases the risk for physical problems such as inflammation, diabetes, and heart risk, and mental health problems such as anxiety, depression, agoraphobia, panic disorder, substance abuse, and PTSD.[57]

Community violence

Unlike bullying which is direct, trauma from community violence is not always directly perpetuated on the child, but is instead the result of being exposed to violent acts and behaviors in the community, such as gang violence, school shootings, riots, or police brutality.[58] Community violence exposure whether direct, or indirect, is associated with many negative mental health outcomes among children and adolescents including internalizing trauma-related symptoms,[59] academic problems,[60] substance abuse,[61] and suicidal ideation.[62]

Evidence also indicates that violence tends to beget more violence; children who witness community violence consistently show higher levels of aggression across developmental periods including early[59] and middle childhood,[63][64] as well as adolescence.[65]

Complex trauma

Complex trauma occurs from exposure to multiple and repetitive episodes of victimization or other traumatic events. Individuals who are exposed to multiple forms of trauma often display a wide range of difficulties compared to those who have only had one of few trauma exposures. For example, cognitive complications (dissociation), affective, somatic, behavioral, relational, and self-attributional problems have been seen in individuals who have experienced complex trauma.[66]

Disasters

Beyond the experience of natural and man-made disasters themselves, disaster-related traumas include the loss of loved ones, disruptions caused by disaster-caused homelessness and hardship and the breakdown of community structures.[67]

Exposure to a natural disaster is a highly stressful experiences that can lead to a wide range of maladaptive outcomes, particularly in children.[68] Exposure to natural disaster constitutes a risk factor for poor psychological health in children and adolescents. Psychological symptoms tend to decline over time after the exposure, it is not a rapid process.[69]

Intimate partner violence

Similar to community violence, intimate partner violence-related trauma is not necessarily directly perpetuated on child, but can be the result of exposure to violence within the household, often of violence perpetuated against one or more caregivers or family members. It is often accompanied by direct physical and emotional abuse of the child.[70] Witnessing violence and threats against a caregiver during early years of life is associated with severe impacts on a child's health and development.

Outcomes for children include psychological distress, behavioral disorders, disturbances in self-regulation, difficulties with social interaction, and disorganized attachment.[71] Children who were exposed to interpersonal violence were more likely to develop long term mental health problems than those with non-interpersonal traumas.[72] The impact of seeing intimate partner violence could be more serious for younger children. Younger children are completely dependent on their caregivers than older children not only for physical care but also emotional care. This is needed for them to develop normal neurological, psychological, and social development. This dependence can contribute to their vulnerability to witnessing violence against their caregivers.

Medical trauma

Medical trauma, sometimes called 'paediatric medical traumatic stress' refers to a set of psychological and physiological responses of children and their families to pain, injury, serious illness, medical procedures, and invasive or frightening treatment experiences. Medical trauma may occur as a response to a single or multiple medical events.[73] In children, they are still developing cognitive skills and because of this they process information differently. They might associate pain with punishment and could believe they did something wrong that led to them being in pain or that they somehow caused their injury.[74]

Children may experience disruptions in their attachment with their caregivers due to their traumatic medical experience. This does depend on the age of the child and their understanding of their medical difficulties. For example, a young child may feel betrayed by their parents if they have had to participate in activities that have cause and contributed to the child's pain such as administering medications or taking them to the doctor. At the same time, the parent-child relationship is strained due to parents feeling powerless, guilt, or inadequacy.[74]

Physical abuse

Child physical abuse is physical trauma or physical injury caused by slapping, beating, hitting, or otherwise harming a child.[75] This abuse is considered non-accidental. Injuries can range from mild bruising to broken bones, skull fractures, and even death.[76] Short term consequences of physical abuse of children include fractures,[77] cognitive or intellectual disabilities, social skills deficits, PTSD, other psychiatric disorders,[76] heightened aggression, and externalizing behaviors,[78] anxiety, risk-taking behavior, and suicidal behavior.[79] Long-term consequences include difficulty trusting others, low self-esteem, anxiety, physical problems, anger, internalization of aggression, depression, interpersonal difficulties, and substance abuse.

Refugee trauma

Refugee-related childhood trauma can take place in the child's country of origin due to war, persecution, or violence, but can also be a result of the process of displacement or even the disruptions and transitions of resettlement into the destination country.[80] Studies of refugee youth report high levels of exposure to war related trauma and have found profound averse consequences of these experiences for children's mental health. Some outcomes from experiencing trauma in refugee children are behavioral problems, mood and anxiety disorders, PTSD, and adjustment difficulty.[81]

Separation trauma

Separation trauma[82] is a disruption in an attachment relationship that disrupts neurological development and can lead to death.[83][84] Chronic separation from a caregiver can be extremely traumatic to a child.[85][86] Additionally, separation from a parental or attachment figure while enduring a separate childhood trauma can also produce withstanding impact on the child's attachment security.[87] This may later be associated with the development of post-traumatic adult symptomology.[87]

Sexual abuse

Traumatic grief

Traumatic grief is distinguished from the traditional grieving process in that the child is unable to cope with daily life, or even remember a loved one outside of the circumstances of their death. This can often be the case when the death is the result of a sudden illness or an act of violence.[88]

Treatment

The health effects of childhood trauma can be mitigated through care and treatment.[89][90][91]

There are many treatments for childhood trauma, including psychosocial treatments and pharmacologic treatments.[89][90][91] Psychosocial treatments can be targeted toward individuals, such as psychotherapy, or targeted towards wider populations, such as school-wide interventions.[89][92] While studies (systematic reviews) of current evidence have shown that many types[93] of treatments are effective, trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy[94] may be the most effective for treating childhood trauma.[91][95]

In contrast, other studies have shown that pharmacologic therapies may be less effective than psychosocial therapies for treating childhood trauma.[89][91] Lastly, early intervention can significantly reduce negative health effects of childhood trauma.[96][97]

Cognitive behavioral therapy

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is the psychological treatment of choice for PTSD and is recommended by best-practice treatment guidelines.[95] The goal of CBT is to help patients change their thoughts, beliefs, and attitudes to better control their emotions.[98] Additionally, it is structured to help patients better cope with trauma and improve their problem-solving skills.[98] Many studies provide evidence that CBT is effective for treating PTSD in terms of magnitude of symptom reduction from pre-treatment levels, and diagnostic recovery.[89][91][99] Associated treatment barriers include stigma, cost, geography and insufficient treatment availability.[100]

Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy

Trauma focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) is a branch of cognitive behavioral therapy designed to treat PTSD cases in children and adolescents.[101] This treatment model combines the principles of CBT with trauma-sensitive approaches.[102] It helps introduce skills to cope with the symptoms of the trauma for both the child and the parent if available, before allowing the child to process the trauma on their own in a safe space.[103] Studies (systematic reviews) have shown trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy to be one of the most effective treatments to minimize the negative psychological effects of childhood trauma, particularly PTSD.[89][91][95][104]

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy (EMDR) is a technique used by therapists to help process traumatic memories.[105] The intervention has the patient recall traumatic memories and use bilateral stimulation such as eye movements or finger tapping to help regulate their emotions.[105] The process is complete when the patient becomes desensitized to the memory and can recall it without having a negative response.[105] A randomized controlled trial showed that EMDR reduced symptoms of PTSD in children who had been exposed to a single-traumatic event, and was cost-effective.[106] Additionally, studies have shown EMDR to be an effective treatment for PTSD.[104]

Dialectical behavior therapy

Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) has been shown to be help prevent self-harm and enhance interpersonal functioning by reducing experiential avoidance and expressed anger through a combination of cognitive behavioral and mindfulness techniques.[107]

Real life heroes

The real life heroes (RLH) treatment, a sequential, attachment-centered treatment intervention for children with Complex PTSD that focuses on 3 primary components: affect regulation, emotionally supportive relationships, and life story integration to build resources and skills for resilience.[108] A study of 126 children found Real Life Heroes treatment to be effective in reducing symptoms of PTSD and in improving behavioral problems.[109]

Narrative-emotion process coding system

The narrative-emotion process coding system (NEPCS) is a behavioral coding system that identifies eight client markers: Abstract Story, Empty Story, Unstoried Emotion, Inchoate Story, Same Old Story, Competing Plotlines Story, Unexpected Outcome Story, and Discovery Story. Each marker varies in the degree to which specific narrative and emotion process indicators are represented in one-minute time segments drawn from videotaped therapy sessions. As enhanced integration of narrative and emotional expression has previously been associated with recovery from complex trauma.[110]

Attachment, Self-Regulation, and Competency framework

The Attachment, Self-Regulation, and Competency (ARC) Framework is an intervention for children and adolescents impacted by complex trauma.[111] The ARC framework is a flexible, component-based intervention for treating children and adolescents who have experienced complex trauma.[111] Theoretically grounded in attachment, trauma, and developmental theories and specifically addresses three core domains impacted by exposure to chronic, interpersonal trauma: attachment, self-regulation, and developmental competencies.[111] A study using data from the US National Child Traumatic Stress Network found that treatment with the ARC framework was effective, reducing behavioral problems and symptoms of PTSD to a similar degree that of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy.[101]

School-wide approaches

Many school-wide interventions that have been studied differ considerably from one another, which limits the strength of the evidence in support of school-wide interventions for treating childhood trauma; however, studies of school-wide approaches show that they tended to be moderately effective, reducing trauma symptoms, encouraging behavior change, and improving self-esteem.[92]

Pharmaceutical treatments

Most studies that evaluate the effectiveness of using pharmaceuticals (medications) for treatment of childhood trauma focus specifically on treating PTSD.[89][91] PTSD is only one health effect that can result from childhood trauma.[112] Few studies evaluate the effectiveness of pharmaceutical treatment for treating other health effects of childhood trauma, besides PTSD.

Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRI) and other anti-depressants are medications that are commonly used to treat the symptoms of PTSD.[113] Studies (systematic reviews) have shown that medications may be less effective than psychosocial therapies for treating PTSD.[89][91] However, medications have been shown to be effective when paired with another form of therapy such as CBT for PTSD.[114]

References

- Pearce J, Murray C, Larkin W (July 2019). "Childhood adversity and trauma: experiences of professionals trained to routinely enquire about childhood adversity". Heliyon. 5 (7): e01900. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01900. PMC 6658729. PMID 31372522.

- van der Kolk BA, Perry JC, Herman JL (December 1991). "Childhood origins of self-destructive behavior". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 148 (12): 1665–71. doi:10.1176/ajp.148.12.1665. PMID 1957928.

- Lupien, Sonia J.; McEwen, Bruce S.; Gunnar, Megan R.; Heim, Christine (2009). "Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 10 (6): 434–445. doi:10.1038/nrn2639. ISSN 1471-0048. PMID 19401723. S2CID 205504945.

- "The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study". Centers for Diesase Control. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- Brown DW, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Edwards VJ, Malarcher AM, Croft JB, Giles WH (January 2010). "Adverse childhood experiences are associated with the risk of lung cancer: a prospective cohort study". BMC Public Health. 10: 20. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-20. PMC 2826284. PMID 20085623.

- Dube SR, Fairweather D, Pearson WS, Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Croft JB (February 2009). "Cumulative childhood stress and autoimmune diseases in adults". Psychosomatic Medicine. 71 (2): 243–50. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181907888. PMC 3318917. PMID 19188532.

- Taylor SE, Lerner JS, Sage RM, Lehman BJ, Seeman TE (December 2004). "Early environment, emotions, responses to stress, and health". Journal of Personality. 72 (6): 1365–93. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.324.5195. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00300.x. PMID 15509286.

- Motzer SA, Hertig V (March 2004). "Stress, stress response, and health". The Nursing Clinics of North America. 39 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1016/j.cnur.2003.11.001. PMID 15062724.

- Miller, Gregory E.; Chen, Edith; Zhou, Eric S. (2007). "If it goes up, must it come down? Chronic stress and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis in humans". Psychological Bulletin. 133 (1): 25–45. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.25. ISSN 0033-2909. PMID 17201569.

- Chapman DP, Whitfield CL, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Edwards VJ, Anda RF (October 2004). "Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood". Journal of Affective Disorders. 82 (2): 217–25. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2003.12.013. PMID 15488250.

- Murphy MO, Cohn DM, Loria AS (March 2017). "Developmental origins of cardiovascular disease: Impact of early life stress in humans and rodents". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 74 (Pt B): 453–465. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.07.018. PMC 5250589. PMID 27450581.

- Aron EN, Aron A, Davies KM (February 2005). "Adult shyness: the interaction of temperamental sensitivity and an adverse childhood environment". Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin. 31 (2): 181–97. doi:10.1177/0146167204271419. PMID 15619591. S2CID 1679620.

- Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T (2012). "The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis". PLOS Medicine. 9 (11): e1001349. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349. PMC 3507962. PMID 23209385.

- Sachs-Ericsson NJ, Sheffler JL, Stanley IH, Piazza JR, Preacher KJ (October 2017). "When Emotional Pain Becomes Physical: Adverse Childhood Experiences, Pain, and the Role of Mood and Anxiety Disorders". Journal of Clinical Psychology. 73 (10): 1403–1428. doi:10.1002/jclp.22444. PMC 6098699. PMID 28328011.

- Carr CP, Martins CM, Stingel AM, Lemgruber VB, Juruena MF (December 2013). "The role of early life stress in adult psychiatric disorders: a systematic review according to childhood trauma subtypes". The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 201 (12): 1007–20. doi:10.1097/NMD.0000000000000049. PMID 24284634. S2CID 205878806.

- Curran, Emma; Adamson, Gary; Rosato, Michael; De Cock, Paul; Leavey, Gerard (2018-05-03). "Profiles of childhood trauma and psychopathology: US National Epidemiologic Survey". Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 53 (11): 1207–1219. doi:10.1007/s00127-018-1525-y. ISSN 0933-7954. PMID 29725700. S2CID 20881161.

- Tognin S, Calem M (1 March 2017). "M122. Impact of Childhood Trauma on Educational Achievement in Young People at Clinical High Risk of Psychosis". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 43 (suppl_1): S255. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbx022.116. PMC 5475870.

- "Effects of Childhood Trauma on Adults". International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- Mehta D, Klengel T, Conneely KN, Smith AK, Altmann A, Pace TW, et al. (May 2013). "Childhood maltreatment is associated with distinct genomic and epigenetic profiles in posttraumatic stress disorder". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (20): 8302–7. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.8302M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1217750110. PMC 3657772. PMID 23630272.

- Provençal N, Suderman MJ, Guillemin C, Massart R, Ruggiero A, Wang D, et al. (October 2012). "The signature of maternal rearing in the methylome in rhesus macaque prefrontal cortex and T cells". The Journal of Neuroscience. 32 (44): 15626–42. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1470-12.2012. PMC 3490439. PMID 23115197.

- Ramo-Fernández L, Schneider A, Wilker S, Kolassa IT (October 2015). "Epigenetic Alterations Associated with War Trauma and Childhood Maltreatment". Behavioral Sciences & the Law. 33 (5): 701–21. doi:10.1002/bsl.2200. PMID 26358541.

- Miller DB, O'Callaghan JP (June 2002). "Neuroendocrine aspects of the response to stress". Metabolism. 51 (6 Suppl 1): 5–10. doi:10.1053/meta.2002.33184. PMID 12040534.

- Xiong F, Zhang L (January 2013). "Role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in developmental programming of health and disease". Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 34 (1): 27–46. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2012.11.002. PMC 3594480. PMID 23200813.

- Krause, Bernardo J.; Artigas, Rocio; Sciolla, Andres F.; Hamilton, James (July 2020). "Epigenetic mechanisms activated by childhood adversity". Epigenomics. 12 (14): 1239–1255. doi:10.2217/epi-2020-0042. ISSN 1750-192X. PMID 32706263. S2CID 220730686.

- Stenz, Ludwig; Schechter, Daniel S.; Serpa, Sandra Rusconi; Paoloni-Giacobino, Ariane (December 2018). "Intergenerational Transmission of DNA Methylation Signatures Associated with Early Life Stress". Current Genomics. 19 (8): 665–675. doi:10.2174/1389202919666171229145656. ISSN 1389-2029. PMC 6225454. PMID 30532646.

- Yehuda R, Halligan SL, Grossman R (2001). "Childhood trauma and risk for PTSD: relationship to intergenerational effects of trauma, parental PTSD, and cortisol excretion". Development and Psychopathology. 13 (3): 733–53. doi:10.1017/S0954579401003170. PMID 11523857. S2CID 23786662.

- Jawahar MC, Murgatroyd C, Harrison EL, Baune BT (2015). "Epigenetic alterations following early postnatal stress: a review on novel aetiological mechanisms of common psychiatric disorders". Clinical Epigenetics. 7 (1): 122. doi:10.1186/s13148-015-0156-3. PMC 4650349. PMID 26583053.

- "Social and Economic Consequences of Child Abuse and Neglect". Child Welfare Information Gateway. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "The Estimated Annual Cost of Child Abuse and Neglect". Prevent Child Abuse America.

- Fox M (2 May 2016). "Poor Parenting Can Be Passed From Generation to Generation". NBC News. Retrieved 2017-03-16.

- "Childhood trauma compromises health via diverse pathways". The Blue Knot Foundation. Archived from the original on 2017-03-22. Retrieved 2017-03-16.

- "Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs): Mental Illness of a Parent". Crow Wing Energized. Archived from the original on 2017-03-22. Retrieved 2017-03-16.

- Roth TL (November 2013). "Epigenetic mechanisms in the development of behavior: advances, challenges, and future promises of a new field". Development and Psychopathology. 25 (4 Pt 2): 1279–91. doi:10.1017/S0954579413000618. PMC 4080409. PMID 24342840.

- Feder A, Nestler EJ, Charney DS (June 2009). "Psychobiology and molecular genetics of resilience". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 10 (6): 446–57. doi:10.1038/nrn2649. PMC 2833107. PMID 19455174.

- Tyrka AR, Ridout KK, Parade SH (November 2016). "Childhood adversity and epigenetic regulation of glucocorticoid signaling genes: Associations in children and adults". Development and Psychopathology. 28 (4pt2): 1319–1331. doi:10.1017/S0954579416000870. PMC 5330387. PMID 27691985.

- Kaplan SJ, Pelcovitz D, Labruna V (October 1999). "Child and adolescent abuse and neglect research: a review of the past 10 years. Part I: Physical and emotional abuse and neglect". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 38 (10): 1214–22. doi:10.1097/00004583-199910000-00009. PMID 10517053.

- Juul SH, Hendrix C, Robinson B, Stowe ZN, Newport DJ, Brennan PA, Johnson KC (February 2016). "Maternal early-life trauma and affective parenting style: the mediating role of HPA-axis function". Archives of Women's Mental Health. 19 (1): 17–23. doi:10.1007/s00737-015-0528-x. PMID 25956587. S2CID 11124814.

- Arnow BA (2004). "Relationships between childhood maltreatment, adult health and psychiatric outcomes, and medical utilization". Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 65: 10–15.

- Collishaw S, Pickles A, Messer J, Rutter M, Shearer C, Maughan B (March 2007). "Resilience to adult psychopathology following childhood maltreatment: evidence from a community sample". Child Abuse & Neglect. 31 (3): 211–29. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.02.004. PMID 17399786.

- Masten AS (March 2001). "Ordinary magic. Resilience processes in development". The American Psychologist. 56 (3): 227–38. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.56.3.227. PMID 11315249.

- Masten AS, Best KM, Garmezy N (October 1990). "Resilience and development: Contributions from the study of children who overcome adversity". Development and Psychopathology. 2 (4): 425–444. doi:10.1017/S0954579400005812. S2CID 145342630.

- "Cultivating positive emotions to optimize health and well-being". Prevention & Treatment. 3: np. 2000. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.194.4228. doi:10.1037/1522-3736.3.0001a (inactive 2022-08-18).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of August 2022 (link) - Tugade MM, Fredrickson BL, Barrett LF (December 2004). "Psychological resilience and positive emotional granularity: examining the benefits of positive emotions on coping and health". Journal of Personality. 72 (6): 1161–90. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00294.x. PMC 1201429. PMID 15509280.

- Roy A, Carli V, Sarchiapone M (October 2011). "Resilience mitigates the suicide risk associated with childhood trauma". Journal of Affective Disorders. 133 (3): 591–4. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2011.05.006. PMID 21621850.

- Wingo AP, Wrenn G, Pelletier T, Gutman AR, Bradley B, Ressler KJ (November 2010). "Moderating effects of resilience on depression in individuals with a history of childhood abuse or trauma exposure". Journal of Affective Disorders. 126 (3): 411–4. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2010.04.009. PMC 3606050. PMID 20488545.

- Poole JC, Dobson KS, Pusch D (February 2017). "Childhood adversity and adult depression: The protective role of psychological resilience". Child Abuse & Neglect. 64: 89–100. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.12.012. PMID 28056359.

- Poole JC, Dobson KS, Pusch D (August 2017). "Anxiety among adults with a history of childhood adversity: Psychological resilience moderates the indirect effect of emotion dysregulation". Journal of Affective Disorders. 217: 144–152. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2017.03.047. PMID 28410477.

- Watson D, Hubbard B (December 1996). "Adaptational Style and Dispositional Structure: Coping in the Context of the Five-Factor Model". Journal of Personality. 64 (4): 737–774. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00943.x.

- Campbell-Sills L, Cohan SL, Stein MB (April 2006). "Relationship of resilience to personality, coping, and psychiatric symptoms in young adults". Behaviour Research and Therapy. 44 (4): 585–99. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2005.05.001. PMID 15998508.

- Yates TM, Egeland B, Sroufe LA (2003). "Rethinking Resilience: A Developmental Process Perspective". Resilience and Vulnerability. pp. 243–266. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511615788.012. ISBN 978-0-521-00161-8.

- "Chapter 3, Understanding the Impact of Trauma.". Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services. Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services (Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series. Vol. 57. Rockville (MD): Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (US). 2014.

- SAMHSA's Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2014.

- Kent, Angela; Waller, Glenn (1998-05-01). "The Impact of Childhood Emotional Abuse: An Extension of the Child Abuse and Trauma Scale". Child Abuse & Neglect. 22 (5): 393–399. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(98)00007-6. ISSN 0145-2134. PMID 9631251.

- Thompson, Anne E.; Kaplan, Carole A. (1996). "Childhood Emotional Abuse". British Journal of Psychiatry. 168 (2): 143–148. doi:10.1192/bjp.168.2.143. ISSN 0007-1250. PMID 8837902. S2CID 8520532.

- Peterson S (2018-03-26). "Bullying". The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Retrieved 2020-10-26.

- deLara EW (September 2019). "Consequences of Childhood Bullying on Mental Health and Relationships for Young Adults". Journal of Child and Family Studies. 28 (9): 2379–2389. doi:10.1007/s10826-018-1197-y. S2CID 149830204.

- Copeland WE, Wolke D, Angold A, Costello EJ (April 2013). "Adult psychiatric outcomes of bullying and being bullied by peers in childhood and adolescence". JAMA Psychiatry. 70 (4): 419–26. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.504. PMC 3618584. PMID 23426798.

- Peterson S (2017-12-08). "Community Violence". The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Retrieved 2020-10-26.

- Fowler PJ, Tompsett CJ, Braciszewski JM, Jacques-Tiura AJ, Baltes BB (January 2009). "Community violence: a meta-analysis on the effect of exposure and mental health outcomes of children and adolescents". Development and Psychopathology. 21 (1): 227–59. doi:10.1017/S0954579409000145. PMID 19144232. S2CID 8075374.

- Busby DR, Lambert SF, Ialongo NS (February 2013). "Psychological symptoms linking exposure to community violence and academic functioning in African American adolescents". Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 42 (2): 250–62. doi:10.1007/s10964-012-9895-z. PMC 4865382. PMID 23277294.

- Vermeiren R, Schwab-Stone M, Deboutte D, Leckman PE, Ruchkin V (March 2003). "Violence exposure and substance use in adolescents: findings from three countries". Pediatrics. 111 (3): 535–40. doi:10.1542/peds.111.3.535. PMID 12612233.

- Lambert SF, Copeland-Linder N, Ialongo NS (October 2008). "Longitudinal associations between community violence exposure and suicidality". The Journal of Adolescent Health. 43 (4): 380–6. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.02.015. PMC 2605628. PMID 18809136.

- Guerra NG, Huesmann LR, Spindler A (October 2003). "Community violence exposure, social cognition, and aggression among urban elementary school children". Child Development. 74 (5): 1561–76. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00623. hdl:2027.42/83426. PMID 14552414.

- Schwartz D, Proctor LJ (August 2000). "Community violence exposure and children's social adjustment in the school peer group: the mediating roles of emotion regulation and social cognition". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 68 (4): 670–83. doi:10.1037/0022-006x.68.4.670. PMID 10965642.

- Bradshaw CP, Rodgers CR, Ghandour LA, Garbarino J (September 2009). "Social–cognitive mediators of the association between community violence exposure and aggressive behavior". School Psychology Quarterly. 24 (3): 199–210. doi:10.1037/a0017362.

- Courtois CA, Gold SN (2009). "The need for inclusion of psychological trauma in the professional curriculum: A call to action". Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 1 (1): 3–23. doi:10.1037/a0015224.

- Peterson S (2018-01-25). "Disasters". The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Retrieved 2020-10-26.

- Hansel TC, Osofsky HJ, Osofsky JD, Speier AH (June 2019). "Katrina inspired disaster screenings and services: School-based trauma interventions". Traumatology. 25 (2): 133–141. doi:10.1037/trm0000178. S2CID 149847964.

- Adebäck P, Schulman A, Nilsson D (January 2018). "Children exposed to a natural disaster: psychological consequences eight years after 2004 tsunami". Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 72 (1): 75–81. doi:10.1080/08039488.2017.1382569. PMID 28990835. S2CID 3082066.

- "Intimate Partner Violence". The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. 2017-10-30. Retrieved 2020-10-26.

- Evans SE, Davies C, DiLillo D (March 2008). "Exposure to domestic violence: A meta-analysis of child and adolescent outcomes". Aggression and Violent Behavior. 13 (2): 131–140. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2008.02.005.

- Lambert, Hilary K.; Meza, Rosemary; Martin, Prerna; Fearey, Eliot; McLaughlin, Katie A. (2017), "Childhood Trauma as a Public Health Issue", Evidence-Based Treatments for Trauma Related Disorders in Children and Adolescents, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 49–66, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46138-0_3, ISBN 978-3-319-46136-6, retrieved 2021-09-22

- Marsac ML, Kassam-Adams N, Delahanty DL, Widaman KF, Barakat LP (December 2014). "Posttraumatic stress following acute medical trauma in children: a proposed model of bio-psycho-social processes during the peri-trauma period". Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 17 (4): 399–411. doi:10.1007/s10567-014-0174-2. PMC 4319666. PMID 25217001.

- Locatelli MG (January 2020). "Play therapy treatment of pediatric medical trauma: A retrospective case study of a preschool child". International Journal of Play Therapy. 29 (1): 33–42. doi:10.1037/pla0000109. S2CID 202276262.

- "Supplemental Material for Differences in Childhood Physical Abuse Reporting and the Association Between CPA and Alcohol Use Disorder in European American and African American Women". Psychology of Addictive Behaviors: adb0000174.supp. 2016. doi:10.1037/adb0000174.supp.

- Kolko DJ (2001). "Child Physical Abuse". In Myers JE, Berliner L, Briere J, Hendrix CT, Reid T, Jenny C (eds.). The APSAC Handbook on Child Maltreatment. SAGE Publications. pp. 21–50. ISBN 978-0-7619-1991-9.

- Hoskote AU, Martin K, Hormbrey P, Burns EC (November 2003). "Fractures in infants: one in four is non-accidental". Child Abuse Review. 12 (6): 384–391. doi:10.1002/car.806.

- Manly JT, Kim JE, Rogosch FA, Cicchetti D (December 2001). "Dimensions of child maltreatment and children's adjustment: contributions of developmental timing and subtype". Development and Psychopathology. 13 (4): 759–82. doi:10.1017/s0954579401004023. PMID 11771907. S2CID 28118238.

- Finzi R, Har-Even D, Shnit D, Weizman A (1 December 2002). "Psychosocial Characterization of Physically Abused Children from Low Socioeconomic Households in Comparison to Neglected and Nonmaltreated Children". Journal of Child and Family Studies. 11 (4): 441–453. doi:10.1023/A:1020983308496. S2CID 140273333.

- Peterson S (2018-01-25). "Refugee Trauma". The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Retrieved 2020-10-26.

- Betancourt TS, Newnham EA, Layne CM, Kim S, Steinberg AM, Ellis H, Birman D (December 2012). "Trauma history and psychopathology in war-affected refugee children referred for trauma-related mental health services in the United States". Journal of Traumatic Stress. 25 (6): 682–90. doi:10.1002/jts.21749. PMID 23225034.

- Charlier T (2010). "Symbolisierung früher Trennungstraumata und Neubildung von Repräsentanzen" [Symbolization of early separation traumas and the formation of new representations]. Psyche (in German). 64 (1): 1–33.

- Ward MJ, Lee SS, Lipper EG (2000). "Failure-to-thrive is associated with disorganized infant-mother attachment and unresolved maternal attachment". Infant Mental Health Journal. 21 (6): 428–442. doi:10.1002/1097-0355(200011/12)21:6<428::aid-imhj2>3.0.co;2-b.

- Muñoz-Hoyos A, Augustin-Morales MC, Ruíz-Cosano C, Molina-Carballo A, Fernández-García JM, Galdó-Munoz G (November 2001). "Institutional childcare and the affective deficiency syndrome: consequences on growth, nutrition and development". Early Human Development. 65 Suppl: S145-52. doi:10.1016/s0378-3782(01)00216-x. PMID 11755045.

- Cook A, Spinazzola J, Ford J, Lanktree C, Blaustein M, Cloitre M, et al. (2005-05-01). "Complex Trauma in Children and Adolescents". Psychiatric Annals. 35 (5): 390–398. doi:10.3928/00485713-20050501-05.

- Kinzie JD, Sack WH, Angell RH, Manson S, Rath B (1986). "The Psychiatric Effects of Massive Trauma on Cambodian Children: I. The Children". Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry. 25 (3): 370–376. doi:10.1016/s0002-7138(09)60259-4.

- Bryant, R. A.; Creamer, M.; O'Donnell, M.; Forbes, D.; Felmingham, K. L.; Silove, D.; Malhi, G.; Hoof, M. van; McFarlane, A. C.; Nickerson, A. (August 2017). "Separation from parents during childhood trauma predicts adult attachment security and post-traumatic stress disorder". Psychological Medicine. 47 (11): 2028–2035. doi:10.1017/S0033291717000472. ISSN 0033-2917. PMID 28535839. S2CID 5181165.

- Peterson S (2018-01-25). "Traumatic Grief". The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Retrieved 2020-10-26.

- Wethington, Holly R.; Hahn, Robert A.; Fuqua-Whitley, Dawna S.; Sipe, Theresa Ann; Crosby, Alex E.; Johnson, Robert L.; Liberman, Akiva M.; Mościcki, Eve; Price, LeShawndra N.; Tuma, Farris K.; Kalra, Geetika (September 2008). "The Effectiveness of Interventions to Reduce Psychological Harm from Traumatic Events Among Children and Adolescents". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 35 (3): 287–313. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2008.06.024. PMID 18692745.

- Ehring, Thomas; Welboren, Renate; Morina, Nexhmedin; Wicherts, Jelte M.; Freitag, Janina; Emmelkamp, Paul M. G. (December 2014). "Meta-analysis of psychological treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder in adult survivors of childhood abuse". Clinical Psychology Review. 34 (8): 645–657. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2014.10.004. ISSN 1873-7811. PMID 25455628.

- Coventry, Peter A.; Meader, Nick; Melton, Hollie; Temple, Melanie; Dale, Holly; Wright, Kath; Cloitre, Marylène; Karatzias, Thanos; Bisson, Jonathan; Roberts, Neil P.; Brown, Jennifer V. E. (August 2020). "Psychological and pharmacological interventions for posttraumatic stress disorder and comorbid mental health problems following complex traumatic events: Systematic review and component network meta-analysis". PLOS Medicine. 17 (8): e1003262. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1003262. ISSN 1549-1676. PMC 7446790. PMID 32813696.

- Avery, Julie C.; Morris, Heather; Galvin, Emma; Misso, Marie; Savaglio, Melissa; Skouteris, Helen (2021). "Systematic Review of School-Wide Trauma-Informed Approaches". Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma. 14 (3): 381–397. doi:10.1007/s40653-020-00321-1. PMC 8357891. PMID 34471456.

- van der Kolk, Bessel A (April 2003). "The neurobiology of childhood trauma and abuse". Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 12 (2): 293–317. doi:10.1016/s1056-4993(03)00003-8. ISSN 1056-4993. PMID 12725013.

- De Bellis, Michael D.; Zisk, Abigail (April 2014). "The Biological Effects of Childhood Trauma". Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 23 (2): 185–222. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2014.01.002. ISSN 1056-4993. PMC 3968319. PMID 24656576.

- Paintain E, Cassidy S (September 2018). "First-line therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder: A systematic review of cognitive behavioural therapy and psychodynamic approaches". Counselling and Psychotherapy Research. 18 (3): 237–250. doi:10.1002/capr.12174. PMC 6099301. PMID 30147450.

- McPherson L, Gatwiri K, Tucci J, Mitchell J, Macnamara N (November 2018). "A paradigm shift in responding to children who have experienced trauma: The Australian treatment and care for kids program". Children and Youth Services Review. 94: 525–534. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.08.031. S2CID 150116205.

- Oosterbaan, Veerle; Covers, Milou L. V.; Bicanic, Iva A. E.; Huntjens, Rafaële J. C.; de Jongh, Ad (2019). "Do early interventions prevent PTSD? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the safety and efficacy of early interventions after sexual assault". European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 10 (1): 1682932. doi:10.1080/20008198.2019.1682932. ISSN 2000-8066. PMC 6853210. PMID 31762949.

- Harris, Stephanie (2012-10-19). "Cognitive Behavioural Therapy: Basics and Beyond (2nd edn.) Judith S. Beck New York: The Guilford Press, 2011. pp. 391, £34.99 (hb)". Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 41 (1): 124–125. doi:10.1017/s135246581200094x. ISBN 978-160918-504-6. ISSN 1352-4658. S2CID 143970899.

- Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. The National Academies Press. 2008-12-18. doi:10.17226/11955. ISBN 978-0-309-10926-0.

- Allen AR, Newby JM, Smith J, Andrews G (December 2015). "Internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy (iCBT) for posttraumatic stress disorder versus waitlist control: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial". Trials. 16 (1): 544. doi:10.1186/s13063-015-1059-5. PMC 4666048. PMID 26628268. S2CID 16947803.

- Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Deblinger E (2006). Treating trauma and traumatic grief in children and adolescents. New York: Guilford Press. ISBN 9781462528400.

- Cohen, Judith A.; Mannarino, Anthony P.; Iyengar, Satish (January 2011). "Community treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder for children exposed to intimate partner violence: a randomized controlled trial". Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 165 (1): 16–21. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.247. ISSN 1538-3628. PMID 21199975.

- Cohen, Judith A.; Mannarino, Anthony P. (July 2015). "Trauma-focused Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Traumatized Children and Families". Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 24 (3): 557–570. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2015.02.005. ISSN 1558-0490. PMC 4476061. PMID 26092739.

- Bisson, J.; Andrew, M. (2007-07-18). Bisson, Jonathan (ed.). "Psychological treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD003388. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003388.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 17636720.

- Shapiro F (2007). "EMDR, adaptive processing, and case conceptualization". Journal of EMDR Practice and Research. 1: 68–87. doi:10.1891/1933-3196.1.2.68. S2CID 145457423.

- de Roos, Carlijn; van der Oord, Saskia; Zijlstra, Bonne; Lucassen, Sacha; Perrin, Sean; Emmelkamp, Paul; de Jongh, Ad (November 2017). "Comparison of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy, cognitive behavioral writing therapy, and wait-list in pediatric posttraumatic stress disorder following single-incident trauma: a multicenter randomized clinical trial". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 58 (11): 1219–1228. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12768. ISSN 1469-7610. PMID 28660669. S2CID 21616164.

- Curtois C (2009). Treating complex traumatic stress disorders: An evidence-based guide. Guildford Press. ISBN 978-1462513390.

- Kagan, Richard; Spinazzola, Joseph (October 2013). "Real Life Heroes in Residential Treatment: Implementation of an Integrated Model of Trauma and Resiliency-Focused Treatment for Children and Adolescents with Complex PTSD". Journal of Family Violence. 28 (7): 705–715. doi:10.1007/s10896-013-9537-6. ISSN 0885-7482. S2CID 15631231.

- Kagan, Richard; Henry, James; Richardson, Margaret; Trinkle, Joanne; LaFrenier, Audrey (September 2014). "Evaluation of Real Life Heroes treatment for children with complex PTSD". Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 6 (5): 588–596. doi:10.1037/a0035879. ISSN 1942-969X.

- Carpenter N, Angus L, Paivio S, Bryntwick E (2 April 2016). "Narrative and emotion integration processes in emotion-focused therapy for complex trauma: an exploratory process-outcome analysis". Person-Centered & Experiential Psychotherapies. 15 (2): 67–94. doi:10.1080/14779757.2015.1132756. S2CID 147513703.

- Blaustein, Margaret E.; Kinniburgh, Kristine M. (2017), "Attachment, Self-Regulation, and Competency (ARC)", Evidence-Based Treatments for Trauma Related Disorders in Children and Adolescents, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 299–319, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46138-0_14, ISBN 978-3-319-46136-6, retrieved 2021-09-14

- Hughes, Karen; Bellis, Mark A.; Hardcastle, Katherine A.; Sethi, Dinesh; Butchart, Alexander; Mikton, Christopher; Jones, Lisa; Dunne, Michael P. (August 2017). "The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Lancet. Public Health. 2 (8): e356–e366. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4. ISSN 2468-2667. PMID 29253477. S2CID 3217580.

- American Psychiatric Association. "Medications for PTSD". www.apa.org. Archived from the original on 2019-07-22. Retrieved 2021-04-03.

- Hien, D.A.; Levin, Frances R.; Ruglass, Lesia; Lopez-Castro, Teresa (January 2015). "Enhancing the effects of cognitive behavioral therapy for PTSD and alcohol use disorders with antidepressant medication: A randomized clinical trial". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 146: e142. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.09.303. ISSN 0376-8716.