Cistern

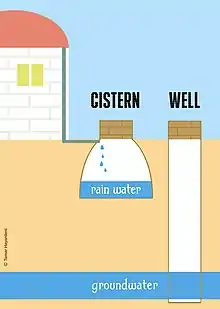

A cistern (Middle English cisterne, from Latin cisterna, from cista, "box", from Greek κίστη kistē, "basket")[1] is a waterproof receptacle for holding liquids, usually water. Cisterns are often built to catch and store rainwater.[2] Cisterns are distinguished from wells by their waterproof linings. Modern cisterns range in capacity from a few litres to thousands of cubic metres, effectively forming covered reservoirs.[3]

Origins

Early domestic and agricultural use

Waterproof lime plaster cisterns in the floors of houses are features of Neolithic village sites of the Levant at, for instance, Ramad and Lebwe,[4] and by the late fourth millennium BC, as at Jawa in northeastern Lebanon, cisterns are essential elements of emerging water management techniques in dry-land farming communities.[5]

The Ancient Roman impluvium, a standard feature of the domus house, generally had a cistern underneath. The impluvium and associated structures collected, filtered, cooled, and stored the water, and also cooled and ventilated the house.

Castle cisterns

In the Middle Ages, cisterns were often constructed in hill castles in Europe, especially where wells could not be dug deeply enough. There were two types: the tank cistern and the filter cistern. Such a filter cistern was built at the Riegersburg in Austrian Styria, where a cistern was hewn out of the lava rock. Rain water passed through a sand filter and collected in the cistern. The filter cleaned the rain water and enriched it with minerals.

Present-day use

Cisterns are commonly prevalent in areas where water is scarce, either because it is rare or has been depleted due to heavy use. Historically, the water was used for many purposes including cooking, irrigation, and washing.[6] Present-day cisterns are often used only for irrigation due to concerns over water quality. Cisterns today can also be outfitted with filters or other water purification methods when the water is intended for consumption. It is not uncommon for a cistern to be open in some manner in order to catch rain or to include more elaborate rainwater harvesting systems. It is important in these cases to have a system that does not leave the water open to algae or to mosquitoes, which are attracted to the water and then potentially carry disease to nearby humans.[7]

Some cisterns sit on the top of houses or on the ground higher than the house, and supply the running water needs for the house. They are often supplied by wells with electric pumps, or are filled manually or by truck delivery, rather than by rainwater collection. Very common throughout Brazil, for example, they were traditionally made of concrete walls (much like the houses themselves), with a similar concrete top (about 5 cm/2 inches thick), with a piece that can be removed for water filling and then reinserted to keep out debris and insects. Modern cisterns are manufactured out of plastic (in Brazil with a characteristic bright blue color, round, in capacities of about 10,000 and 50,000 liters (2641 and 13,208 gallons)). These cisterns differ from water tanks in the sense that they are not entirely enclosed and sealed with one form, rather they have a lid made of the same material as the cistern, which is removable by the user.

To keep a clean water supply, the cistern must be kept clean. It is important to inspect them regularly, keep them well enclosed, and to occasionally empty and clean them with a proper dilution of chlorine and to rinse them well. Well water must be inspected for contaminants coming from the ground source. City water has up to 1ppm (parts per million) chlorine added to the water to keep it clean, and in many areas can be ordered to be delivered directly to the cistern by truck (a typical price in Brazil is BRL$50, US$20 for 10,000 liters). If there is any question about the water supply at any point (source to tap), then the cistern water should not be used for drinking or cooking. If it is of acceptable quality and consistency, then it can be used for (1) toilets, and housecleaning; (2) showers and handwashing; (3) washing dishes, with proper sanitation methods,[8] and for the highest quality, (4) cooking and drinking. Water of non-acceptable quality for the aforementioned uses may still be used for irrigation. If it is free of particulates but not low enough in bacteria, then boiling may also be an effective method to prepare the water for drinking.

Many greenhouses rely on a cistern to help meet their water needs, particularly in the United States. Some countries or regions, such as Flanders, Bermuda and the U.S. Virgin Islands, have strict laws requiring that rainwater harvesting systems be built alongside any new construction, and cisterns can be used in these cases. In Bermuda, for example, its familiar white-stepped roofs seen on houses are part of the rainwater collection system, where water is channeled by roof gutters to below-ground cisterns.[9] Other countries, such as Japan, Germany, and Spain, also offer financial incentives or tax credit for installing cisterns.[10] Cisterns may also be used to store water for firefighting in areas where there is an inadequate water supply. The city of San Francisco, notably, maintains fire cisterns under its streets in case the primary water supply is disrupted. In many flat areas the use of cisterns is encouraged to absorb excess rainwater which otherwise can overload sewage or drainage systems by heavy rains (certainly in urban areas where a lot of ground is surfaced and doesn't let the ground absorb water).

Bathing

In some southeast Asian countries such as Malaysia and Indonesia showers are traditionally taken by pouring water over one's body with a dipper (this practice comes from before piped water was common). Many bathrooms even in modern houses are constructed with a small cistern to hold water for bathing by this method.

Toilet cisterns

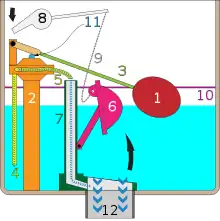

1. float, 2. fill valve, 3. lift arm, 4. tank fill tube, 5. bowl fill tube, 6. flush valve flapper, 7. overflow tube, 8. flush handle, 9. chain, 10. fill line, 11. fill valve shaft, 12. flush tube

The modern water closet (WC) or toilet utilises a cistern to reserve and hold the correct amount of water required to flush the toilet bowl. In earlier toilets, the cistern was located high above the toilet bowl and connected to it by a long pipe. It was necessary to pull a hanging chain connected to a release valve located inside the cistern in order to flush the toilet. Modern toilets may be close coupled, with the cistern mounted directly on the toilet bowl and no intermediate pipe. In this arrangement, the flush mechanism (lever or push button) is usually mounted on the cistern. Concealed cistern toilets, where the cistern is built into the wall behind the toilet, are also available. A flushing trough is a type of cistern used to serve more than one WC pan at one time. These cisterns are becoming less common however. The cistern was the genesis of the modern bidet.

At the beginning of the flush cycle, as the water level in the toilet cistern tank drops, the flush valve flapper falls back to the bottom, stopping the main flow to the flush tube. Because the tank water level has yet to reach the fill line, water continues to flow from the tank and bowl fill tubes. When the water again reaches the fill line, the float will release the fill valve shaft and water flow will stop.

One Million Cisterns Program

In northeastern Brazil, the One Million Cisterns Program (Programa 1 Milhão de Cisternas or P1MC) has assisted local people with water management. The Brazilian government adopted this new policy of rainwater harvesting in 2013.[11] The Semi-Arid Articulation (ASA) has been providing managerial and technological support to establish cement-layered containers, called cisterns, to harvest and store rainwater for small farm-holders in 34 territories of nine states where ASA operates (MG, BA, SE, AL, PE, PB, RN, CE and PI).[12]

The rainwater falling on the rooftops are passed through pipelines or gutters and stored in the cistern.[13] The cistern is covered with a lid to avoid evaporation. Each cistern has a capacity of 16,000 liters. Water collected in it during 3–4 months of the rainy season can sustain the requirement for drinking, cooking, and other basic sanitation purposes for rest of the dry periods. By 2016, 1.2 million RWH cisterns were implemented for human consumption alone.[14] After positive results of P1MC, the government introduced another program named "One Land, Two Water Program" (Uma Terra, Duas Águas, P1 + 2), which provides a farmer with another slab cistern to support agricultural production.[15]

Notable examples

- Basilica Cistern in Istanbul, Turkey

- Aljibe of the Palacio de las Veletas in Cáceres, Spain

- Portuguese cistern (Mazagan) in El Jadida, Morocco

- Cistern in Silves, Portugal

- Matera, southern Italy

- Asa of Judah had built a cistern, and the prophet Jeremiah was later thrown in it after prophesying the Babylonian invasion

- Cistern in Genesis 37:20, 22

See also

- Ab anbar, Persian cistern

- List of Roman cisterns

- Stepwell

- Taanka

- Water tank

Gallery

Plastic cistern

Plastic cistern Remains of a Nabataean cistern north of Makhtesh Ramon, southern Israel

Remains of a Nabataean cistern north of Makhtesh Ramon, southern Israel Cistern known as Tekir ambarı in Silifke, Mersin Province, Turkey

Cistern known as Tekir ambarı in Silifke, Mersin Province, Turkey Aljibe of the Palacio de las Veletas, Cáceres, Spain

Aljibe of the Palacio de las Veletas, Cáceres, Spain Cistern in the Peniche Fortress, Peniche, Portugal

Cistern in the Peniche Fortress, Peniche, Portugal Sign indicating a cistern in Japan

Sign indicating a cistern in Japan

References

- Webster's Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary, 1990 edition, etymology of "cistern".

- "Cisterns".

- "Cistern Design" (PDF). North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. Retrieved 2020-04-13.

- Robert Miller, "Water use in Syria and Palestine from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age", World Archaeology, 2.3 (February 1980:331-341) p. 334.

- Roberts, N. (1977). "Water conservation in ancient Arabia". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 7: 134–46.

- Mays, Larry; Antoniou, George; Angelakis, Andreas (2013). "History of Water Cisterns: Legacies and Lessons" (PDF). Water. 5 (4): 1916–1940. doi:10.3390/w5041916.

- al-Kibsi, Huda (2007-09-29). "Yemen takes another look at cisterns". Yemen Observer. Archived from the original on 2012-02-08. Retrieved 2020-05-11.

- "Naturnaher Umgang mit Regenwasser" (PDF). Bayerisches Landesamt für Umwelt LfU (in German). Retrieved 2020-04-12.

- Low, Harry (23 December 2016). "Why houses in Bermuda have white stepped roofs". BBC News. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- Scheidewig. "Geld sparen durch Zisternennutzung". Garten-Zisternen (in German). Retrieved 2020-04-13.

- Lindoso, D.P.; Eiró, F.; Bursztyn, M.; Rodrigues-Filho, S.; Nasuti, S. (2018). "Harvesting water for living with drought: Insights from the Brazilian human coexistence with semi-aridity approach towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals". Sustainability. 10 (3): 622. doi:10.3390/su10030622.

- Pragana, Verônica (2017-12-29). "Acesso à água para produção é ampliado para mais de 6,8 mil famílias do Semiárido". IRPAA - Instituto Regional da Pequena Agropecuária Apropriada.

- Lindoso, D.P.; Eiró, F.; Bursztyn, M.; Rodrigues-Filho, S.; Nasuti, S. (2018). "Harvesting water for living with drought: Insights from the Brazilian human coexistence with semi-aridity approach towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals". Sustainability. 10 (3): 622. doi:10.3390/su10030622.

- "Programa Cisternas democratiza acesso à água no Semiárido". Government of Brazil. 2016.

- Lindoso, D.P.; Eiró, F.; Bursztyn, M.; Rodrigues-Filho, S.; Nasuti, S. (2018). "Harvesting water for living with drought: Insights from the Brazilian human coexistence with semi-aridity approach towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals". Sustainability. 10 (3): 622. doi:10.3390/su10030622.

External links

- Old House Web - Historic Water Conservation.