Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine

Case Western Reserve School of Medicine (CWRU SOM, CaseMed) is the medical school of Case Western Reserve University, a private research university in Cleveland, Ohio. It is the largest biomedical research center in Ohio.[1]

| Type | Private medical school |

|---|---|

| Established | 1843 |

Parent institution | Case Western Reserve University |

| Dean | Stanton L. Gerson, MD |

Academic staff | 11,049 |

| Students | 1,206 |

| Location | Cleveland , Ohio , United States |

| Website | case |

| |

History

On November 1, 1843, under President George Edmond Pierce, five faculty members including Jared Potter Kirtland and John Delamater, and sixty-seven students began the first medical lectures at the Medical Department of Western Reserve College (also known as the Cleveland Medical College) in Hudson, Ohio.[2][3] Kirtland and Delamater had previously been instructors at a medical college started in 1834, the Medical Department of Willoughby University of Lake Erie, which had closed in 1843 due to faculty disagreements.[2] Other faculty from that Medical Department went on to found Willoughby Medical College of Columbus, a precursor to the Ohio State University College of Medicine.[4]

Women in Medicine

In 1852, the medical school became the second in the U.S. to graduate a woman, Nancy Talbot Clark. 1854 MD alumna, Emily Blackwell became the third woman in the US to receive a regular medical degree. Six of the first seven women in the United States to receive medical degrees from recognized allopathic medical schools graduated from Western Reserve University between 1850 and 1856, which included Marie Zakrzewska.

Flexner Report

In 1909, Abraham Flexner surveyed and evaluated each of the 155 medical schools then extant in North America, with his results published the following year in what came to be known as the Flexner Report. The results proved shocking: most "medical schools," for example, had entrance requirements no more stringent than either high school diploma or "rudiments or the recollection of a common school education."

Only sixteen schools required at least two years of college as an entrance requirement, and of these, Johns Hopkins, Harvard, and Western Reserve were the only schools to require an undergraduate degree. Although Johns Hopkins represented his ideal, Flexner also singled out the Medical Department of Western Reserve University for its praiseworthy admission standards and facilities. Flexner referred to Western Reserve as "already one of the substantial schools in the country." In a letter to Western Reserve president Charles Franklin Thwing he said, "The Medical Department of Western Reserve University is, next to Johns Hopkins..., the best in the country."

Western Reserve curriculum

A little over 40 years later, in 1952, the Western Reserve University School of Medicine revolutionized medical education with the "new curriculum of 1952" and more advanced stages in 1968. This was the most progressive medical curriculum in the country at that time, integrating the basic and clinical sciences.[5][6] L. O. Krampitz chaired the subcommittee which implemented the curriculum reform.[7]

Research history

Development of the modern technique for human blood transfusion using a cannula to connect blood vessels; first large-scale medical research project on humans in a study linking iodine with goiter prevention; pioneering use of drinking water chlorination; discovery of the cause of ptomaine food poisoning and development of serum against it and similar poisons; first surgical treatments of coronary artery disease; discovery of early treatment of strep throat infections to prevent rheumatic fever; development of an early heart-lung machine to be used during open-heart surgery procedures; discovery of the Hageman factor in blood clotting, a major discovery in blood coagulation research; first description of how staphylococcus infections are transmitted, leading to required hand-washing between patients in infant nurseries; first description of what was later named Reye's syndrome; research leading to FDA approval of clozapine, the most advanced treatment for schizophrenia in 40 years at the time; discovery of the gene for osteoarthritis; and creation with Athersys, Inc., of the world's first human artificial chromosome.

Health Education Campus

In 2019, the School of Medicine relocated to the Samson Pavilion Health Education Campus on the campus of the Cleveland Clinic, a $515 million building project, amid a multi-million dollar joint fundraising campaign between CWRU and the Cleveland Clinic.[8] The campus houses students Case Western Reserve School of Medicine (CCLCM and traditional MD programs), Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing and Case School of Dental Medicine, all of which—with the exception of CCLCM—had previously held classes on the campus of CWRU and University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center.[9] The move, announced in 2013, was a major contributing factor for University Hospitals to shift its name from University Hospitals Case Medical Center to University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center in 2016, as well as renegotiate its affiliation agreement with CWRU that same year.[10]

Academics

Prospective students have the option of three degree paths leading to a medical degree at the School of Medicine: the University Program, the College Program, or the Medical Scientist Training Program.

University Program

The University Program is a traditional four-year Doctor of Medicine program designed to train well-rounded physicians in a curriculum called the Western Reserve2 (WR2) which is built on four cornerstones of clinical mastery, research and scholarship, leadership, and civic professionalism to prepare students for the ongoing practice of evidence-based medicine in the rapidly changing healthcare environment of the 21st century. The goal of this program is to challenge students so that they affect positive change through treating disease, promoting health, and understanding the social and behavioral context of illness. The four-year curriculum unites the disciplines of medicine and public health into a single, integrated program that trains future physicians to consider the interplay between the biology of disease and the social and behavioral context of illness, between the care of the individual patient and the health of the public, and between clinical medicine and population medicine.

The University Program seeks to create physician-scholars who are leaders in science, practice and health care policy. Students learn primarily through small group discussions, large group experiences, lectures, interactive anatomy sessions, clinical skills training and patient-based activities. The learning process is supplemented by a rich array of digital resources, including virtual microscopy, ultrasound, and Microsoft Hololens - HoloAnatomy.

The environment encourages scientific inquiry and self-directed learning. Students are immersed in a graduate-school atmosphere characterized by flexibility, independent study and collegial interaction with faculty. Students complete in-depth, mentored research experiences based on their individual interests, with the goal of understanding the scientific process so that they may critically read and analyze scientific literature and know how to formulate hypotheses. These lifelong learning skills are essential in both clinical and research-oriented practices. All students also receive mentoring and individualized career counseling as members of one of six academic student affairs societies.

The principles of health and population medicine are firmly embedded within the University Program curriculum from the moment students begin their training at CWRU in an introductory five-week block called, "Becoming a Doctor."

In typical programs, students begin their medical education by studying basic science at the molecular level, not fully aware of the relevance that this knowledge will have in their future education or how it relates to the actual practice of medicine. The University Program begins differently, however, with an introduction to health and disease within the broader context of society. This introduction provides both a perspective and a framework for subsequent learning of biomedical and population sciences.

One of the hallmarks of the University Program in the first two years of WR2 is Case Inquiry (IQ). Case Inquiry (IQ) is a student-centered, small group learning method that is adapted from the “new” Problem Based Learning (PBL) approach introduced at McMaster University School of Medicine in 2005. IQ is the cornerstone of learning in the WR2 Curriculum. Eight students are joined with one faculty facilitator which comprises an "IQ Team" that meets three times a week to approach two patient cases that naturally evoke inquiry and motivation for learning.

Students develop their own learning objectives for each of two cases on Mondays and then return on Wednesdays and Fridays to discuss the reading, research and learning that they have accomplished relating to their objectives for each case. Resources and supplemental resources are provided to compliment the learning for each case. Wednesday and Friday IQ sessions are highly discussion based where students collaborate to understand key concepts and build knowledge. As with other components of the WR2 Curriculum, the IQ process promotes deep concept learning. Unlike many forms of more traditional PBL, all students within the IQ team are responsible for researching all student-generated learning objectives. This assures that all students take primary responsibility for their own learning and are prepared to discuss all objectives.

Each IQ session ends with a phase called "checkout" that allows for the continuous quality improvement of the team function and provides regular opportunity for self-reflection and peer feedback. Throughout their experience in IQ, students develop skills of teamwork, professionalism, critical thinking and effective utilization of resources (Evidence-based IQ), including primary literature.

A number of exercises are developmentally introduced to the IQ teams over the course of the first two years of WR2, the Foundations of Medicine and Health, with the goals of promoting reflection, practice in presenting patients, development of clinical reasoning and interprofessional education.

The Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine

The Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine (CCLCM) is an educational program within the CWRU School of Medicine administered in conjunction with Cleveland Clinic. The program is five years, including a dedicated year for research. The Cleveland Clinic established the school in 2002 with a $100 million gift from Norma and Al Lerner,[11] and CCLCM accepted its first class of students in 2004.[12] Physician researcher Eric Topol played an important role in securing the donation from the Lerner family.[13] Topol served as Provost and Chief Academic Officer at CCLCM until 2006, when his position was eliminated amid controversy regarding his criticism of Vioxx and disagreements with other Cleveland Clinic leaders, including then-CEO Toby Cosgrove.[14]

The class size each year is 32 students, and the curriculum is notable for its lack of class rank, pre-clinical or clinical grading, or end-of-course examinations.[12] In 2008, Cleveland Clinic announced that all students entering the program would receive full-tuition scholarships, representing the first medical school program in the United States not to charge students tuition.[15] The Cleveland Clinic, rather than CWRU, is responsible for all financial aspects of the school.[12] Administration of the school, including deans, administrative staff, and admissions, is separate from the School of Medicine, which provides oversight over academic affairs at CCLCM.[12]

The Lerner College of Medicine program is one of three distinct medical school programs, specifically called the College Program, within the CWRU School of Medicine. College Program students are awarded a special degree by Case Western Reserve University: Medical Doctor with Special Qualifications in Biomedical Research.

As of summer 2019, students from both CCLCM and the CWRU School of Medicine University Program, along with CWRU nursing, dental medicine and physician assistant students, share the same learning environment. Called the Health Education Campus, located across from Cleveland Clinic's main entrance, this state-of-the-future space was designed specifically to allow these groups of training medical professionals to learn with—and from—each other.

CCLCM students have access to all the resources available to other CWRU medical students, including shared social events start at orientation, participation in Doc Opera, special interest groups, panels, and other activities. Students from the three programs - University Program, College Program, and MSTP - are together for events such as the White Coat Ceremony, Match Day and Commencement. Students also interact in their required clinical rotations at area hospitals and healthcare facilities.

Medical Scientist Training Program

The Medical Scientist Training Program awards MD and PhD degrees upon graduation. Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine was the first medical school to offer the dual degree MD-PhD program to its students in 1956, nearly a decade before the National Institutes of Health developed the first Medical Scientist Training Program.[16]

In 2002, the School of Medicine became the third institution in history to receive the highest review possible from the body that grants accreditation to U.S. and Canadian medical degree programs, the Liaison Committee on Medical Education.[17]

Primary Teaching Hospitals

- University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center

- Rainbow Babies & Children's Hospital

- UH Seidman Cancer Center

- UH MacDonald Women's Hospital

- Cleveland Clinic

- MetroHealth

- Louis Stokes Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center

Other teaching affiliates

- St. Vincent Charity Hospital

- Circle Health Services

Student life

Academic Societies

The CWRU School of Medicine School is divided into six societies named after famous CaseMed alums. Upon matriculation, students in the University Program and MSTP are assigned to a society. Each has a Society Dean who serves as an academic and career adviser to the students.[19] The societies are:[19]

- Frederick C. Robbins Society

- Emily Blackwell-Elizabeth McKinley Society

- David Satcher Society

- Joseph Wearn Society

- H. Jack Geiger Society

- Julie Gerberding Society

Every year, the six societies compete in "ISC Picnic" for the infamous Society Cup in a series of events (e.g. soccer, flag football, relay races etc.).

Doc Opera

Every year, students at Case Western Reserve SOM write, direct and perform a full-length musical parody, lampooning Case Western Reserve, their professors, and themselves. It is a longstanding tradition that began in the 1980's and in recent years, the show has been a benefit for the Student Run Health Clinic.[20]

Role in Cleveland and Ohio

.jpg.webp)

During 2007, the economic impact of the School of Medicine and its affiliates on the State of Ohio equaled $5.82 billion and accounted for more than 65,000 Ohio jobs.[21] The role of Case Western Reserve University in the Cleveland economy has been reported on by The Economist magazine.[22]

In popular culture

Notable alumni and faculty

1800s

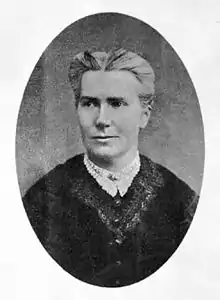

- Nancy Talbot Clark (1852 MD alumna)[26] - second woman in the United States to earn a medical degree.†

- Emily Blackwell (1854 MD alumna)[27] - third woman in the United States to earn a medical degree and the sister of Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman in the United States to earn a medical degree.†

- Cordelia A. Greene (1855 MD alumna) - founder, Castile Sanitarium; benefactor, Cordelia A. Greene Library.†

- Marie Elizabeth Zakrzewska (1856 MD alumna) - founder of the New England Hospital for Women and Children (known today as The Dimock Center).

- George Washington Crile (1887 MD alumnus) - Performed first blood transfusion. Established Lakeside Hospital of what is now University Hospitals Case Medical Center,[28] and later co-founded Cleveland Clinic.[29] Crile was a graduate of Wooster Medical College which merged to form modern day CaseMed.[30][31][32]

- John A. Rice (1851 MD alumnus) - member of the Wisconsin State Senate.

†Six of the first seven women in the United States to receive medical degrees from recognized allopathic medical schools graduated from Western Reserve University (as it was called then) between 1850 and 1856.

1900s

- Thomas Wingate Todd, Professor of Anatomy

- Matthew N. Levy, Professor of Physiology, co-author of Berne & Levy's Principles of Physiology

- Theodor Kolobow (1958 MD alumnus), NIH researcher and inventor of the spiral coil membrane lung[33]

2000s

- Li Tao (2014 MD alumnus), creator of Microbe Invader

Nobel laureates

Alumni

- 1980 - Paul Berg (1952 PhD in Biochemistry alumnus), Nobel Prize in Chemistry for pioneering research in recombinant DNA technology.[34]

- 1985 & 1997 - H. Jack Geiger (1958 MD alumnus), Though not a recipient of Nobel prize directly, he was the founding member and past president of Physicians for Human Rights[35][36] which shared the 1997 Nobel Peace Prize[37] as part of International Campaign to Ban Landmines. He also was a founding member of Physicians for Social Responsibility which shared the 1985 Nobel Peace Prize as part of International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War.

- 1994 - Alfred Gilman (1969 MD-PhD alumnus), Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for co-discovery of G Proteins[38]

- 1998 - Ferid Murad (1965 MD-PhD alumnus), Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for role in the discovery of nitric oxide in cardiovascular signaling [39]

- 2003 - Peter C. Agre (1978 Internal Medicine alumnus), Nobel Prize in Chemistry for discovering Aquaporin protein that clarified how salts and water are transported out of and into the cells of the body, leading to a better understanding of many diseases of the kidneys, heart, muscles and nervous system.[40]

Faculty

- 1923 - John J.R. Macleod (Professor of Physiology), Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, for discovery of Insulin[41]

- 1938 - Corneille J.F. Heymans, Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for work on carotid sinus reflex[42]

- 1954 - Frederick C. Robbins (Dean of CaseMed), Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, for work on polio virus, which led to development of polio vaccines; past president of the Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences.[43]

- 1971 - Earl W. Sutherland (Chair of Pharmacology), Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, for establishing identity and importance of cyclic adenosine monophosphate or cyclic AMP in regulation of cell metabolism.[38] Sutherland discovered cAMP while at CaseMed.

- 1988 - George H. Hitchings, Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, for research leading to development of drugs to treat leukemia, organ transplant rejection, gout, herpes virus, and AIDS-related bacterial and pulmonary infections.[44]

Public health

- Sidney Katz (1948 MD alumnus) - Pioneering American physician, scientist, educator, author, and public servant. Most noted for creating the first Activities of Daily Living (ADL) Scale

- Jesse Leonard Steinfeld (1949 MD alumnus) - U.S. Surgeon General (1969 to 1973), most noted for achieving widespread fluoridation of water, requiring prescription drugs to be effective, and strengthening the Surgeon General's Warning on cigarettes.[45]

- David Satcher (1970 MD-PhD alumnus) - U.S. Surgeon General under President Bill Clinton, and first African-American director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention[46]

- Julie L. Gerberding (1981 MD alumnus) - first woman director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention[47]

- Michael Ehlert (2007 MD alumnus) - 2007-08 National President of the American Medical Student Association.[48]

- John Brockman (2012 MD alumnus) - 2010-11 National President of the American Medical Student Association.[49]

Other

- 1912 - Professor Roger Perkins pioneered the process of chlorinating drinking water.[50]

- 1915 - Henry Gerstenberger (alumnus and pediatrics professor) first simulated milk formula for infants.

- 1927 - Immunologist Enrique Ecker discovered the cause of ptomaine food poisoning and development of an antiserum.

- 1935 - Claude Beck (Surgery residency alumnus; 1924-1971 Professor of Cardiovascular Surgery - first such position in US)[51] -

- Performed first surgical treatment of coronary artery disease (1935)[52]

- Performed first defibrillation using machine he built with James Rand (1947)[53]

- Developed concept of Beck's Triad

- Started the first CPR teaching course for medical professionals (1950).

- 1950s - Professor Frederick Cross developed first heart-lung machine for use in open heart surgeries.

- 1961 - Professor Austin Weisburger performed first successful genetic alteration of human cells in a test tube.

- 1969 - William Insull, MD describes the role of cholesterol in blood vessel disease.

- 1975 - Discovery that human renin, an enzyme produced by the kidney, is involved in hypertension

- 1990 - National team led by rheumatologist Roland Moskowitz discovers gene for osteoarthritis.

- 1991 - James A. Schulak, MD, and colleagues perform first triple organ transplant in Ohio-a kidney, liver and pancreas.

- 1997 - Team led by Professor Huntington Willard (Chair of Genetics) create world's first artificial human chromosome.

- M. Scott Peck (1963 MD alumnus) - psychiatrist and author of The Road Less Traveled

- 2004 - Craig Smith (1977 MD alumnus) leads the cardiac surgery team which performs President Bill Clinton's coronary artery bypass surgery.[54]

- Richard Walsh, MD (Chair of Medicine, Case Medical Center) - Current editor of Hurst's The Heart Manual of Cardiology.[55]

- Peter Tippett (1983 MD-PhD alumnus) - Inventor of early anti-virus software.[56][57]

- Alfredo Palacio (Internal Medicine alumnus) - President of Ecuador (2005–2007).

- David Jenkins- won the men's gold medal for figure skating during the 1960 Winter Olympics in Squaw Valley, California[58]

- Renee Salas – emergency medicine physician known for her work on climate change

- Peter Pronovost - intensive care physician known for his work on patient safety

See also

- List of Case Western people

- Case School of Dental Medicine

References

- "Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine | Clinical Activities". Archived from the original on 2012-08-19. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- "Medicine". Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. Case Western Reserve University. 11 May 2018. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- "About - School of Medicine - School of Medicine - Case Western Reserve University". School of Medicine - School of Medicine - Case Western Reserve University.

- Paulson, George. "Celebrating 100 Years, 1914-2014: And Weren't We Here Earlier?" (PDF). House Call. Medical Heritage Center at The Ohio State University. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- "History". School of Medicine | School of Medicine | Case Western Reserve University. 2018-05-18. Retrieved 2022-10-19.

- Bandaranayake, Raja C. (27 January 2022). The Integrated Medical Curriculum. CRC Press. ISBN 9780429533310.

- Williams, Greer; Henning, Margaret (1980). Western Reserve's Experiment in Medical Education and Its Outcome. Oxford University Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-19-502679-5.

- Litt, Steven (21 July 2020). "Is CWRU-Cleveland Clinic Health Education Campus end of big-box era as Clinic shifts focus?". Plain Dealer. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- Litt, Steven (2015-10-01). "Cleveland Clinic, CWRU break ground on $515M Health Education Campus including dental clinic in Hough". Plain Dealer. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- Coutre, Lydia (8 September 2016). [UH dropping 'Case' from flagship medical center name "UH dropping 'Case' from flagship medical center name"]. Crain's Cleveland Business. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help) - Boulian, Tracy (26 December 2010). "The biggest gift they ever got". Plain Dealer. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- Fishleder, AJ; Henson, LC; Hull, AL (April 2007). "Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine: An Innovative Approach to Medical Education and the Training of Physician Investigators". Academic Medicine. 82 (4): 390–6. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e318033364e. PMID 17414197.

- Robbins, Gary (15 September 2012). "Eric Topol's tough prescription for improving medicine". San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- Mortland, Shannon (9 February 2006). "Topol leaving for Case". Crain's Business Cleveland. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- Wang, Shirley (15 May 2008). "Cleveland Clinic's Medical School To Offer Tuition-Free Education". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- "Medical Scientist Training Program". School of Medicine | School of Medicine | Case Western Reserve University. 2018-05-22. Retrieved 2019-10-02.

- "Case Western Reserve University". www.case.edu. Archived from the original on 2009-10-13. Retrieved 2009-11-12.

- "Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine | About the School". Archived from the original on 2012-02-23. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- "Academic Societies". CWRU School of Medicine. 20 February 2019. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- "Doc Opera 2020". School of Medicine | School of Medicine | Case Western Reserve University. 2018-10-29. Retrieved 2021-02-04.

- "About | School of Medicine | School of Medicine | Case Western Reserve University". Casemed.case.edu. Retrieved 2019-05-21.

- "The hopeful laundry".

- "Boston Med | Doctors and Nurses | Jeff Ustin M.D. | ABC News". Archived from the original on 2010-07-15. Retrieved 2010-07-19.

- "Boston Med | Doctors and Nurses | Rahul Rathod M.D. | ABC News". Archived from the original on 2010-06-28. Retrieved 2010-07-19.

- "Boston Med | Doctors and Nurses | Elizabeth Blume M.D. | ABC News". Archived from the original on 2010-07-16. Retrieved 2010-07-19.

- "About - School of Medicine - School of Medicine - Case Western Reserve University". School of Medicine - School of Medicine - Case Western Reserve University.

- "School of Medicine - Error". casemed.case.edu.

- "Case Surgery: Surgical Residency Program: General Information: Chairperson's Welcome Message". Archived from the original on 2009-09-06. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- "Mission, Vision, Values - Cleveland Clinic". Cleveland Clinic.

- "Cleveland Heights Historical Society - People". www.chhistory.org.

- "Dittrick Medical History Center - Case Western Reserve University". Archived from the original on 2008-09-07. Retrieved 2009-11-12.

- "Case Western Reserve University". www.case.edu. Archived from the original on 2014-02-21. Retrieved 2009-11-12.

- Trahanas, John M.; Kolobow, Mary Anne; Hardy, Mark A.; Berra, Lorenzo; Zapol, Warren M.; Bartlett, Robert H. (2016). ""Treating Lungs"- The Scientific Contributions of Dr. Theodor Kolobow". ASAIO Journal. 62 (2): 203–210. doi:10.1097/MAT.0000000000000323. ISSN 1058-2916. PMC 4790827. PMID 26720733.

- "Paul Berg - Curriculum Vitae". nobelprize.org.

- "Dr. Jack Geiger Profile". Archived from the original on 2012-05-17. Retrieved 2016-02-09.

- "Physicians for Human Rights - PHR Board of Directors". physiciansforhumanrights.org. Archived from the original on 2010-06-29. Retrieved 2009-11-12.

- "Physicians for Human Rights - Press Room". physiciansforhumanrights.org. Archived from the original on 2010-06-29. Retrieved 2009-11-23.

- "Department of Pharmacology". pharmacology.case.edu. Archived from the original on 2015-11-13. Retrieved 2009-11-12.

- "Ferid Murad - Autobiography". Archived from the original on 2009-11-21. Retrieved 2009-11-12.

- "Peter Agre - Biographical". nobelprize.org.

- "About - School of Medicine - School of Medicine - Case Western Reserve University". School of Medicine - School of Medicine - Case Western Reserve University.

- "Corneille Heymans - Biographical". nobelprize.org.

- "Frederick C. Robbins - Biographical". nobelprize.org.

- "George H. Hitchings - Biographical". nobelprize.org.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-09-16. Retrieved 2009-11-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "School of Medicine - Error". casemed.case.edu.

- "Dr. Julie Gerberding resigns as director of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention". 10 January 2009.

- "Case Western Reserve University - News Center". blog.case.edu.

- "National President". Archived from the original on 2010-08-14. Retrieved 2010-08-08.

- "About - School of Medicine - School of Medicine - Case Western Reserve University". School of Medicine - School of Medicine - Case Western Reserve University.

- "Biography of Claude S. Beck". Archived from the original on 2009-03-07. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- Case faculty Claude Beck - "Biography of Claude S. Beck". Archived from the original on 2009-03-07. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- Case faculty Claude Beck's first defibrillation article - "Ventricular fibrillation of long duration abolished by electric shock", JAMA, 1947

- Case alums leads Bill Clinton's surgical team: https://www.nytimes.com/2004/09/07/national/07doctor.html?_r=1

- Fuster, Valentin. "Hurst's the Heart, 12th Edition / Edition 12 by Valentin Fuster | 9780071478861 | Hardcover | Barnes & Noble®". Search.barnesandnoble.com. Retrieved 2019-05-21.

- "Alumni Relations: Case Western Reserve University". Archived from the original on 2009-06-19. Retrieved 2009-12-27.

- Case alum Peter Tippett developed Norton AntiVirus - http://ciso.issa.org/about/peter-tippett.php

- "News About Skaters", Skating magazine, November 1960