Clone (cell biology)

A clone is a group of identical cells that share a common ancestry, meaning they are derived from the same cell.[1]

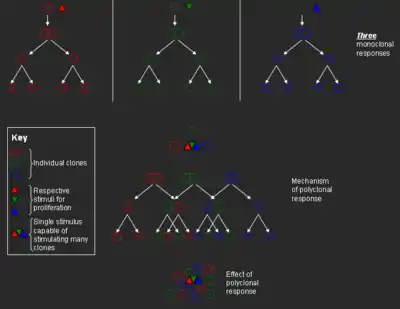

Clonality implies the state of a cell or a substance being derived from one source or the other. Thus there are terms like polyclonal—derived from many clones; oligoclonal[2]—derived from a few clones; and monoclonal—derived from one clone. These terms are most commonly used in context of antibodies or immunocytes.

Contexts

This concept of clone assumes importance as all the cells that form a clone share common ancestry, which has a very significant consequence: shared genotype.

- One of the most prominent usage is in describing a clone of B cells. The B cells in the body have two important phenotypes (functional forms)—the antibody secreting, terminally differentiated (that is, they cannot divide further) plasma cells, and the memory and the naive cells—both of which retain their proliferative potential.

- Another important area where one can talk of "clones" of cells is neoplasms.[3] Many of the tumors derive from one (sufficiently) mutated cell, so they are technically a single clone of cells. However, during course of cell division, one of the cells can get mutated further and acquire new characteristics to diverge as a new clone. However, this view of cancer onset has been challenged in recent years and many tumors have been argued to have polyclonal origin,[4] i.e. derived from two or more cells or clones, including malignant mesothelioma.[5]

- All the granulosa cells in a Graafian follicle are in fact clones.

- Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria is a disorder of bone marrow cells resulting in shortened life of red blood cells, which is also a result of clonal expansion, i.e., all the altered cells are originally derived from a single cell, which also somewhat compromises the functioning of other "normal" bone marrow cells.[6]

Basis of clonal proliferation

Most other cells cannot divide indefinitely as after a few cycles of cell division the cells stop expressing an enzyme telomerase. The genetic material, in the form of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), continues to shorten with each cell division, and cells eventually stop dividing when they sense that their DNA is critically shortened. However, this enzyme in "youthful" cells replaces these lost bits (nucleotides) of DNA, thus making almost unlimited cycles of cell division possible. It is believed that the above-mentioned tissues have a constitutional elevated expression of telomerase. When ultimately many cells are produced by a single cell, clonal expansion is said to have taken place.

Concept of clonal colony

A somewhat similar concept is that of a clonal colony (also called a genet), wherein the cells (usually unicellular) also share a common ancestry, but which also requires the products of clonal expansion to reside at "one place", or in close proximity. A clonal colony would be well exemplified by a bacterial culture colony, or the bacterial films that are more likely to be found in vivo (e.g., in infected multicellular hosts). Whereas, the cells of clones dealt with here are specialized cells of a multicellular organism (usually vertebrates), and reside at quite distant places. For instance, two plasma cells belonging to the same clone could be derived from different memory cells (in turn with shared clonality) and could be residing in quite distant locations, such as the cervical (in the neck) and inguinal (in the groin) lymph nodes.

Paramecium clonal reproduction and aging

The single-cell eukaryote Paramecium tetraurelia can undergo both asexual and sexual reproduction. Asexual or clonal reproduction occurs by binary fission. Binary fission involves mitosis-like behavior of the chromosomes similar to that of cells in higher organisms. The sexual forms of reproduction are autogamy, a kind of self-fertilization, and conjugation, a kind of sexual interation between different cells. Clonal asexual reproduction can be initiated after completion of autogamy or conjugation. P. tetraurelia is able to replicate asexually for many generations but the dividing cells gradually age and after about 200 cell divisions, if the cells fail to undergo another autogamy or conjugation, they lose vitality and expire. This process is referred to as clonal aging. Experiments by Smith-Sonneborn,[7] Holmes and Holmes[8] and Gilley and Blackburn[9] showed that accumulation of DNA damage is the likely cause of clonal aging in P. tetraurelia. This aging process has similarities to the aging process in multicellular eukaryotes (See DNA damage theory of aging).

See also

- Clone (B-cell biology)

- Cloning

- List of animals that have been cloned

- Polyclonal antibodies

- Polyclonal response

- Tumour heterogeneity

References

- "Clone definition – Medical Dictionary definitions of popular medical terms easily defined on MedTerms". MedicineNet.com. 2013-08-28.

- "oligoclonal – Definition from Merriam-Webster's Medical Dictionary". Archived from the original on 2008-03-15. Retrieved 2008-05-05.

- Pozo-Garcia, Lucia; Diaz-Cano, Salvador J.; Taback, Bret; Hoon, Dave S.B. (January 2003). "Clonal origin and expansions in neoplasms: biologic and technical aspects must be considered together". The American Journal of Pathology. 162 (1): 353–355. doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63826-6. PMC 1851102. PMID 12507918.

- Parsons, Barbara L. (September 2008). "Many different tumor types have polyclonal tumor origin: evidence and implications". Mutation Research. 659 (3): 232–47. doi:10.1016/j.mrrev.2008.05.004. PMID 18614394.

- Comertpay, Sabahattin; Pastorino, Sandra; Tanji, Mika; Mezzapelle, Rosanna; Strianese, Oriana; et al. (4 December 2014). "Evaluation of clonal origin of malignant mesothelioma". Journal of Translational Medicine. 12 (1): 301. doi:10.1186/s12967-014-0301-3. PMC 4255423. PMID 25471750.

- Bunn, Franklin; Wendell, Rosse (2005). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. Vol. 1 (16th ed.). The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. p. 616. ISBN 0-07-144746-6.

- Smith-Sonneborn, J. (1979). "DNA repair and longevity assurance in Paramecium tetraurelia". Science. 203 (4385): 1115–1117. Bibcode:1979Sci...203.1115S. doi:10.1126/science.424739. PMID 424739

- Holmes, George E.; Holmes, Norreen R. (July 1986). "Accumulation of DNA damages in aging Paramecium tetraurelia". Molecular and General Genetics. 204 (1): 108–114. doi:10.1007/bf00330196. PMID 3091993. S2CID 11992591

- Gilley, David; Blackburn, Elizabeth H. (1994). "Lack of telomere shortening during senescence in Paramecium" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 91 (5): 1955–1958. Bibcode:1994PNAS...91.1955G. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.5.1955. PMC 43283. PMID 8127914