Cognitive rehabilitation therapy

Cognitive rehabilitation refers to a wide range of evidence-based interventions[1][2][3][4] designed to improve cognitive functioning in brain-injured or otherwise cognitively impaired individuals to restore normal functioning, or to compensate for cognitive deficits.[5] It entails an individualized program of specific skills training and practice plus metacognitive strategies. Metacognitive strategies include helping the patient increase self-awareness regarding problem-solving skills by learning how to monitor the effectiveness of these skills and self-correct when necessary.

| Cognitive rehabilitation therapy | |

|---|---|

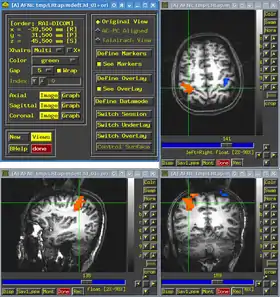

Effects of cognitive rehabilitation therapy, assessed using fMRI. | |

| Specialty | neurology/psychiatry |

Cognitive rehabilitation therapy (offered by a trained therapist) is a subset of Cognitive Rehabilitation (community-based rehabilitation, often in traumatic brain injury; provided by rehabilitation professionals) and has been shown to be effective for individuals who had a stroke in the left or right hemisphere.[6] or brain trauma.[7] A computer-assisted type of cognitive rehabilitation therapy called cognitive remediation therapy has been used to treat schizophrenia, ADHD, and major depressive disorder.[8][9][10][11][12]

Cognitive rehabilitation builds upon brain injury strategies involving memory,[13] executive functions, activities planning and "follow through" (e.g., memory, task sequencing, lists).[14]

It may also be recommended for traumatic brain injury, the primary population for which it was developed in the university medical and rehabilitation communities,[15][16][17][18] such as that sustained by U.S. Representative Gabby Giffords, according to Dr. Gregory J. O'Shanick of the Brain Injury Association of America.[19] Her new doctor has confirmed that it will be part of her rehabilitation.[20] Cognitive rehabilitation may be part of a comprehensive community services program and integrated into residential services, such as supported living, supported employment, family support, professional education, home health (as personal assistance),[21][22] recreation, or education programs in the community.

Cognitive rehabilitation for spatial neglect following stroke

The current body of evidence is uncertain on the efficacy of cognitive rehabilitation for reducing the disabling effects of neglect and increasing independence remains unproven.[23] However, there is limited evidence that cognitive rehabilitation may have an immediate beneficial effect on tests of neglect.[23] Overall, no rehabilitation approach can be supported by evidence for spatial neglect.

Assessments

According to the standard text by Sohlberg and Mateer:[24]

Individuals and families respond differently to different interventions, in different ways, at different times after injury. Premorbid functioning, personality, social support, and environmental demands are but a few of the factors that can profoundly influence outcome. In this variable response to treatment, cognitive rehabilitation is no different from treatment for cancer, diabetes, heart disease, Parkinson's disease, spinal cord injury, psychiatric disorders, or any other injury or disease process for which variable response to different treatments is the norm.

Nevertheless, many different statistical analyses of the benefits of this therapy have been carried out. One study made in 2002 analyzed 47 treatment comparisons and reported "a differential benefit in favor of cognitive rehabilitation in 37 of 47 (78.7%) comparisons, with no comparison demonstrating a benefit in favor of the alternative treatment condition."[6]

An internal study conducted by the Tricare Management Agency in 2009 is cited by the US Department of Defense as its reason for refusing to pay for this therapy for veterans who have had traumatic brain injury. According to Tricare, "There is insufficient, evidence-based research available to conclude that cognitive rehabilitation therapy is beneficial in treating traumatic brain injury."[25] The ECRI Institute, whose report serves as the basis for this decision by the Department of Defense, has summed up their own findings this way:[5]

In our report, we carried out several meta-analyses using data from 18 randomized controlled trials. Based on data from these studies, we were able to conclude the following:

- Adults with moderate to severe traumatic brain injury who receive social skills training perform significantly better on measures of social communication than patients who receive no treatment.

- Adults with traumatic brain injury who receive comprehensive cognitive rehabilitation therapy report significant improvement on measures of quality of life compared to patients who receive a less intense form of therapy.

The strength of the evidence supporting our conclusions was low due to the small number of studies that addressed the outcomes of interest. Further, the evidence was too weak to draw any definitive conclusions about the effectiveness of cognitive rehabilitation therapy for treating deficits related to the following cognitive areas: attention, memory, visuospacial skills, and executive function. The following factors contributed to the weakness of the evidence: differences in the outcomes assessed in the studies, differences in the types of cognitive rehabilitation therapy methods/strategies employed across studies, differences in the control conditions, and/or insufficient number of studies addressing an outcome.

Citing this 2009 assessment, US Department of Defense, one of the federal agencies not responsible for health care decisions in the US, has declared that cognitive rehabilitation therapy is scientifically unproved and should refer their concerns to the US Department of Health and Human Services, US Budget and Management, and/or the Government Accountability Office (GAO). As a result, it refuses to cover the cost of cognitive rehabilitation for brain-injured veterans.[25][26] Cost-benefit and cost-effectiveness studies, together with an analysis of personnel and veterans' services for new our emerging groups in head and brain injuries, are recommended.

See also

- Rehabilitation (neuropsychology)

- Cognitive remediation therapy

- Rehabilitation psychology

- Rehabilitation: Community-based

- Rehabilitation: Hospital-based units

References

- Cicerone, Keith D.; Dahlberg, Cynthia; Kalmar, Kathleen; Langenbahn, Donna M.; Malec, James F.; Bergquist, Thomas F.; Felicetti, Thomas; Giacino, Joseph T.; Harley, J.Preston (December 2000). "Evidence-based cognitive rehabilitation: Recommendations for clinical practice". Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 81 (12): 1596–1615. doi:10.1053/apmr.2000.19240. ISSN 0003-9993. PMID 11128897.

- Cicerone, Keith D.; Dahlberg, Cynthia; Malec, James F.; Langenbahn, Donna M.; Felicetti, Thomas; Kneipp, Sally; Ellmo, Wendy; Kalmar, Kathleen; Giacino, Joseph T. (August 2005). "Evidence-Based Cognitive Rehabilitation: Updated Review of the Literature From 1998 Through 2002". Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 86 (8): 1681–1692. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2005.03.024. ISSN 0003-9993. PMID 16084827.

- Cicerone, Keith D.; Langenbahn, Donna M.; Braden, Cynthia; Malec, James F.; Kalmar, Kathleen; Fraas, Michael; Felicetti, Thomas; Laatsch, Linda; Harley, J. Preston (April 2011). "Evidence-Based Cognitive Rehabilitation: Updated Review of the Literature From 2003 Through 2008". Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 92 (4): 519–530. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2010.11.015. ISSN 0003-9993. PMID 21440699.

- Cicerone, Keith D.; Goldin, Yelena; Ganci, Keith; Rosenbaum, Amy; Wethe, Jennifer V.; Langenbahn, Donna M.; Malec, James F.; Bergquist, Thomas F.; Kingsley, Kristine (March 2019). "Evidence-Based Cognitive Rehabilitation: Systematic Review of the Literature From 2009 Through 2014". Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 100 (8): 1515–1533. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2019.02.011. hdl:1805/18829. ISSN 0003-9993. PMID 30926291. S2CID 88480565.

- "Cognitive Rehabilitation Therapy for Traumatic Brain Injury: What We Know and Don't Know about Its Efficacy" (PDF). ECRI Institute. 2011-01-21. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-04-19. Retrieved 2014-04-17.

Approaches to cognitive rehabilitation therapy are generally separated into two broad categories: restorative and compensatory.

- Keith D. Cicerone; Cynthia Dahlberg; James F. Malec; Donna M. Langenbahn; Thomas Felicetti; Sally Kneipp; Wendy Ellmo; Kathleen Kalmar; Joseph T. Giacino; J. Preston Harley; Linda Laatsch; Philip A. Morse; Jeanne Catanese (August 2002). "Evidence-Based Cognitive Rehabilitation: Updated Review of the Literature From 1998 Through 2002". Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. xxx: Elsevier. 86 (8): 1681–1692. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2005.03.024. PMID 16084827. Retrieved 2011-01-22.

The overall analysis of 47 treatment comparisons, based on class I studies included in the current and previous review, reveals a differential benefit in favor of cognitive rehabilitation in 37 of 47 (78.7%) comparisons, with no comparison demonstrating a benefit in favor of the alternative treatment condition.

- Soderback I.; Ekholm J. (1992). "January–March). Medical and social factors affecting behavior patterns in patients with acquired brain damage: a study of patients living at home three years after incident". Disability and Rehabilitation. 14 (1): 30–35. doi:10.3109/09638289209166424. PMID 1586757.

- Elgamal S, McKinnon MC, Ramakrishnan K, Joffe RT, MacQueen G (Sep 2007). "Successful computer-assisted cognitive remediation therapy in patients with unipolar depression: a proof of principle study". Psychol. Med. 37 (9): 1229–38. doi:10.1017/S0033291707001110. PMID 17610766. S2CID 19958026.

- Wykes T (May 2007). "Cognitive remediation therapy in schizophrenia: randomised controlled trial". Br J Psychiatry. 190: 421–7. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.106.026575. PMID 17470957.

- Wykes T (Aug 2007). "Cognitive remediation therapy (CRT) for young early onset patients with schizophrenia: an exploratory randomized controlled trial". Schizophr. Res. 94 (1–3): 221–30. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2007.03.030. PMID 17524620. S2CID 46117743.

- O'Connell RG, Bellgrove MA, Dockree PM, Robertson IH (Dec 2006). "Cognitive remediation in ADHD: effects of periodic non-contingent alerts on sustained attention to response". Neuropsychol Rehabil. 16 (6): 653–65. doi:10.1080/09602010500200250. PMID 17127571. S2CID 38725935.

- Stevenson CS, et al. (Oct 2002). "A cognitive remediation programme for adults with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder". Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 36 (5): 610–6. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.01052.x. PMID 12225443. S2CID 24904215.

- Zencius A.; Wesolowski M.; Burke W.H. (1990). "January–March). A comparison of four memory strategies with traumatically brain-injured clients". Brain Injury. 4 (1): 33–38. doi:10.3109/02699059009026146. PMID 2297598.

- Burke W.H.; Zencius A.H.; Weslowski M.D.; Doubleday F. (1991). "Improving executive function disorders in brain-injured clients". Brain Injury. 5 (3): 241–252. doi:10.3109/02699059109008095. PMID 1933075.

- Ben-Yishay, Diller L (1993). "Cognitive remediation in traumatic brain injury: Update and issues". Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 74 (2): 204–213. PMID 8431107.

- Crowley J.; Miles J. (1991). "Cognitive remediation in pediatric head injury: A case study". Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 16 (5): 611–627. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/16.5.611. PMID 1744809.

- Gordon W.; Hibbard M.; Kreutzer J. (1989). "Cognitive remediation: Issues in research and practice". Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 4 (3): 76–84. doi:10.1097/00001199-198909000-00011.

- Kreutzer, J. & Wehman, P. (1991). Cognitive Rehabilitation for Persons with Traumatic Brain Injury: A Functional Approach. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

- Thomas M. Burton (2011-01-10). "Brain at Risk Despite Quick Aid". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2011-01-21.

"The rapid treatment she received needs to be matched by a seamless course of rehabilitation such as cognitive rehabilitation," Dr. O'Shanick said.

- "'Intensive Rehabilitation' Is Next for Giffords, New Doctor Says". ABC News Radio. 2011-01-21. Retrieved 2011-01-29.

The key is get into intensive rehabilitation...Bringing in lots of different people from different specialties to work as a coordinated team, speech, cognitive, physical rehabilitation.

- Watson, S. (1991). PAS and head injury. In: J. Weissman, J. Kennedy, & S.Litvak, Personal Perspectives on Personal Assistance Services. (pp. 72-75). Oakland, CA: Rehabilitation Research and Training Center on Public Policy and Independent Living, World Institute on Disability.

- Ulciny, G. & Jones, M. (1985). Enhancing the attendant management skills of persons with disabilities. American Rehabilitation, 18-20.

- Bowen, Audrey; Hazelton, Christine; Pollock, Alex; Lincoln, Nadina B (2013-07-01). "Cognitive rehabilitation for spatial neglect following stroke". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013 (7): CD003586. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003586.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6464849. PMID 23813503.

- McKay Moore Sohlberg; Catherine A Mateer (2001). Cognitive rehabilitation: an integrative neuropsychological approach. Guilford Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-57230-613-4.

- Andrew Tilghman (2011-01-01). "Military insurer denies coverage of new brain injury treatment". USA Today. Retrieved 2011-01-21.

In an internal 2009 study, the Tricare Management Agency found that cognitive rehabilitation therapy is scientifically unproved and does not warrant coverage as a stand-alone treatment for brain injuries.

- Letter to The Honorable Robert Gates from Senator Claire McCaskill (January 19, 2011)