Constipation in children

Constipation in children refers to the medical condition of constipation in children. It is a functional gastrointestinal disorder.

| Constipation in children | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Pediatrics |

Presentation

Children have different bowel movement patterns than adults. In addition, there is a wide spectrum of normalcy when considering children's bowel habits.[1] On average, infants have 3-4 bowel movements/day, and toddlers have 2-3 bowel movements per day. At around age 4, children develop an adult-like pattern of bowel movements (1-2 stools/day). Children benefit from scheduled toilet breaks, once early in the morning and 30 minutes after meals.[2][3] The Rome III Criteria for constipation in children helps to define constipation for various age groups.

Causes

While it is difficult to assess an exact age at which constipation most commonly arises, children frequently experience constipation in conjunction with life-changes. Examples include: toilet training, starting or transferring to a new school, and changes in diet.[1] Especially in infants, changes in formula or transitioning from breast milk to formula can cause constipation. Fortunately, the majority of constipation cases are not tied to a medical disease, and treatment can be focused on simply relieving the symptoms.[4]

Congenital causes

A number of diseases present at birth can result in constipation. They are as a group uncommon with Hirschsprung's disease (HD) being the most common.[5] HD is more common in males than females, affecting 1 out of 5000 babies. In people with HD, specific types of cells called 'neural crest cells' fail to migrate to parts of the colon. This causes the affected portion of the colon to be unable to contract and relax to help push out a bowel movement. The affected portion of the colon remains contracted, making it difficult for stool to pass through.[6] Concern for HD should be raised in a child who has not passed stool during the first 48 hours of life. Milder forms of HD, in which only a small portion of the colon is affected, can present later in childhood as constipation, abdominal pain, and bloating.[6] Similar disorders to HD include anal achalasia and hypoganglionosis. In hypoganglionosis, there is a low number of neural crest cells, so the colon remains contracted. In anal achalasia, the internal anal sphincter remains contracted, making it difficult for stool to pass. However, there is a normal number of neural crest cells present.[4]

There are also congenital structural anomalies that can lead to constipation, including anterior displacement of the anus, imperforate anus, strictures, and small left colon syndrome.[4] Anterior displacement of the anus can be diagnosed on physical exam.[7] The disease causes constipation because the inappropriate positioning of the anus which make it difficult to pass a bowel movement. Imperforate anus is an anus that ends in a blind pouch and does not connect to the rest of the person's intestines. Small left colon syndrome is a rare disease in which the left side of the babies colon has a small diameter, which makes it difficult for stool to pass. A risk factor for small left colon syndrome is having a mother with diabetes.[4]

Some symptoms that may indicate an underlying disease include:[1]

- Bowel movements that contain blood.

- Severe abdominal bloating.

- Peri-anal fistula

- Absent anal wink reflex

- Sacral dimple

- Failure to thrive

Diagnosis

The Rome process suggests a diagnosis of constipation in children fewer than 4 years old when the child has 2 or more of the following complaints for at least 1 month.[4] For children older than 4 years, there must be 2 of these complaints for at least 2 months.

- 2 or fewer bowel movements per week

- Passing large bowel movements

- On physical exam, a doctor may find large amounts of feces within the child's rectum.

- A child who is already toilet trained has at least 1 accident per week involving a bowel movement.

- Child demonstrates withholding behavior in which he or she actively tries not to pass a bowel movement.

- Hard stools

- Pain with defecation.

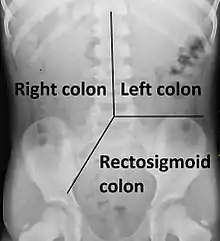

For children, the degree of constipation may be scored by the Leech or the Barr systems:

- The Leech system assigns a score of 0 to 5 based on the amount of feces:[9]

- 0: no visible feces

- 1: scanty feces visible

- 2: mild fecal loading

- 3: moderate fecal loading

- 4: severe fecal loading

- 5: severe fecal loading with bowel dilatation

- These score are assigned separately for the right colon, the left colon and the rectosigmoid colon, resulting in a maximum score of 15. A Leech score of 9 or greater is regarded as positive for constipation.[9]

- The Barr system rates both the amount and consistency of the faeces, and assigns a score separately for the ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon and rectum. Its maximum score is 22, and a score of 10 or greater is regarded as positive for constipation.[10]

Treatment

Lactulose and milk of magnesia have been compared with polyethylene glycol (PEG) in children. All had similar side effects, but PEG was more effective at treating constipation.[11][12] Osmotic laxatives are recommended over stimulant laxatives.[13]

Epidemiology

There is wide variation in the rates of constipation as reported by research in various countries.[14] The variation in research data makes it challenging to describe the true global situation.[14]

Approximately 3% of children have constipation, with girls and boys being equally affected.[4] With constipation accounting for approximately 5% of general pediatrician visits and 25% of pediatric gastroenterologist visits, the symptom carries a significant financial impact upon our healthcare system.[1]

Society and culture

Constipation is often emotionally stressful for children and their caregivers.[15] It is common for parents to bring their children to doctors for this condition.[15] The experience of going to a doctor for this can be stressful.[15]

Too often, children at doctors receive unnecessary health care when they get medical imaging for constipation.[16] Children should only get tests when there is an indication.[16]

References

- Colombo, Jennifer M.; Wassom, Matthew C.; Rosen, John M. (2015-09-01). "Constipation and Encopresis in Childhood". Pediatrics in Review. 36 (9): 392–401, quiz 402. doi:10.1542/pir.36-9-392. ISSN 1526-3347. PMID 26330473. S2CID 35482415.

- Walia R, Mahajan L, Steffen R (October 2009). "Recent advances in chronic constipation". Curr Opin Pediatr. 21 (5): 661–6. doi:10.1097/MOP.0b013e32832ff241. PMID 19606041. S2CID 11606786.

- Bharucha AE (2007). "Constipation". Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology. 21 (4): 709–31. doi:10.1016/j.bpg.2007.07.001. PMID 17643910.

- Tabbers, M.M.; DiLorenzo, C.; Berger, M.Y.; Faure, C.; Langendam, M.W.; Nurko, S.; Staiano, A.; Vandenplas, Y.; Benninga, M.A. (2014). "Evaluation and Treatment of Functional Constipation in Infants and Children". Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 58 (2): 265–281. doi:10.1097/mpg.0000000000000266. PMID 24345831. S2CID 13834963.

- Wexner, Steven (2006). Constipation: etiology, evaluation and management. New York: Springer.

- Wesson, David (November 9, 2016). "UpToDate: Constipation". UpToDate. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

- Pediatrics, American Academy of (1986-08-01). "Congenital Anterior Displacement of Anus". Pediatrics in Review. 8 (2): 38–62. doi:10.1542/pir.8-2-38. ISSN 0191-9601.

- Koppen, Ilan J. N.; Yacob, Desale; Di Lorenzo, Carlo; Saps, Miguel; Benninga, Marc A.; Cooper, Jennifer N.; Minneci, Peter C.; Deans, Katherine J.; Bates, D. Gregory; Thompson, Benjamin P. (2016). "Assessing colonic anatomy normal values based on air contrast enemas in children younger than 6 years". Pediatric Radiology. 47 (3): 306–312. doi:10.1007/s00247-016-3746-0. ISSN 0301-0449. PMC 5316394. PMID 27896373.

- Leech, Susan C.; McHugh, Kieran; Sullivan, P. B. (1999). "Evaluation of a method of assessing faecal loading on plain abdominal radiographs in children". Pediatric Radiology. 29 (4): 255–258. doi:10.1007/s002470050583. ISSN 0301-0449. PMID 10199902. S2CID 9542750.

- G., Anthony; H., Kathleen (2012). "The Role of Diagnostic Tests in Constipation in Children". Constipation - Causes, Diagnosis and Treatment. doi:10.5772/29213. ISBN 978-953-51-0237-3.

- "Is PEG (Polyethylene Glycol) a more effective laxative than Lactulose in the treatment of a child who is constipated?". BestBETs. 16 July 2007.

- Candy D, Belsey J (February 2009). "Macrogol (polyethylene glycol) laxatives in children with functional constipation and faecal impaction: a systematic review". Arch. Dis. Child. 94 (2): 156–60. doi:10.1136/adc.2007.128769. PMC 2614562. PMID 19019885.

- "Osmotic laxative are preferable to the use of stimulant laxatives in the constipated child". BestBETs. 9 November 2007.

- Boronat, Alexandre Canon; Ferreira-Maia, Ana Paula; Matijasevich, Alicia; Wang, Yuan-Pang (2017). "Epidemiology of functional gastrointestinal disorders in children and adolescents: A systematic review". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 23 (21): 3915–3927. doi:10.3748/wjg.v23.i21.3915. PMC 5467078. PMID 28638232.

- Ferrara, Lucille R.; Saccomano, Scott J. (July 2017). "Constipation in children". The Nurse Practitioner. 42 (7): 30–34. doi:10.1097/01.NPR.0000520418.32331.6e. PMID 28622255. S2CID 32386388.

- Ferguson, Catherine Craun; Gray, Matthew P.; Diaz, Melissa; Boyd, Kevin P. (July 2017). "Reducing Unnecessary Imaging for Patients With Constipation in the Pediatric Emergency Department". Pediatrics. 140 (1): e20162290. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-2290. PMID 28615355.