Dancing plague of 1518

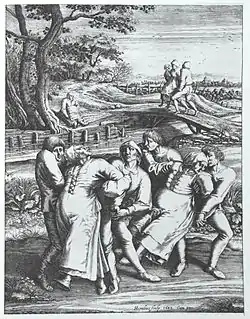

The Dancing Plague of 1518, or Dance Epidemic of 1518, was a case of dancing mania that occurred in Strasbourg, Alsace (modern-day France), in the Holy Roman Empire from July 1518 to September 1518. Somewhere between 50 and 400 people took to dancing for weeks.

Events

The outbreak began in July 1518 when a woman began to dance fervently in a street in Strasbourg.[1] By early September, the outbreak began to subside.[2]

Historical documents, including "physician notes, cathedral sermons, local and regional chronicles, and even notes issued by the Strasbourg city council" are clear that the victims danced;[1] it is not known why. Historical sources agree that there was an outbreak of dancing after a single woman started dancing,[3] and the dancing did not seem to die down. It lasted for such a long time that it even attracted the attention of the Strasbourg magistrate and bishop, and some number of doctors ultimately intervened, putting the afflicted in a hospital.

Events similar to this are said to have occurred throughout the medieval age including 11th century in Kölbigk, Saxony, where it was believed to be the cause of demonic possession or divine judgment.[4] In 15th century Apulia, Italy,[5] a woman was bitten by a tarantula, the venom making her dance convulsively. The only way to cure the bite was to "shimmy" and to have the right sort of music available, which was an accepted remedy by scholars like Athanasius Kircher.[6]

Contemporaneous explanations included demonic possession and overheated blood.[2]

Veracity of deaths

Controversy exists over whether people ultimately danced to their deaths. Some sources claim that for a period the plague killed around fifteen people per day,[7] but the sources of the city of Strasbourg at the time of the events did not mention the number of deaths, or even if there were fatalities. There do not appear to be any sources contemporaneous to the events that make note of any fatalities.[8]

The main source for the claim is John Waller, who has written several journal articles on the subject, and the book A Time to Dance, a Time to Die: The Extraordinary Story of the Dancing Plague of 1518. The sources cited by Waller that mention deaths were all from later accounts of the events. There is also uncertainty around the identity of the initial dancer (either an unnamed woman or "Frau Troffea") and the number of dancers involved (somewhere between 50 and 400). Of the six chronicle accounts, four support Lady Troffea as the first dancer.[9]

Modern theories

Food poisoning

Some believe[2] the dancing could have been brought on by food poisoning caused by the toxic and psychoactive chemical products of ergot fungi (ergotism), which grows commonly on grains (such as rye) used for baking bread. Ergotamine is the main psychoactive product of ergot fungi; it is structurally related to the drug lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD-25) and is the substance from which LSD-25 was originally synthesized. The same fungus has also been implicated in other major historical anomalies, including the Salem witch trials.[10][11]

In The Lancet, John Waller argues that "this theory does not seem tenable, since it is unlikely that those poisoned by ergot could have danced for days at a time. Nor would so many people have reacted to its psychotropic chemicals in the same way. The ergotism theory also fails to explain why virtually every outbreak occurred somewhere along the Rhine and Moselle rivers, areas linked by water but with quite different climates and crops".[7]

Stress-induced mass hysteria

This could have been a florid example of psychogenic movement disorder happening in mass hysteria or mass psychogenic illness, which involves many individuals suddenly exhibiting the same bizarre behavior. The behavior spreads rapidly and broadly in an epidemic pattern.[12] This kind of comportment could have been caused by elevated levels of psychological stress, caused by the ruthless years (even by the rough standards of the early modern period) the people of Alsace were suffering.[7]

Waller speculates that the dancing was "stress-induced psychosis" on a mass level, since the region where the people danced was riddled with starvation and disease, and the inhabitants tended to be superstitious. Seven other cases of dancing plague were reported in the same region during the medieval era.[13]

This psychogenic illness could have created a chorea (from the Greek khoreia meaning "to dance"), a situation comprising random and intricate unintentional movements that flit from body part to body part. Diverse choreas (St. Vitus' dance, St. John's dance, and tarantism) were labeled in the Middle Ages referring to the independent epidemics of "dancing mania" that happened in central Europe, particularly at the time of the plague.[14][15][16]

References

- Viegas, Jennifer (1 August 2008). "'Dancing Plague' and Other Odd Afflictions Explained". Discovery News. Discovery Communications. Archived from the original on 13 October 2012. Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- Bauer, Patricia. "Dancing Plague of 1518". Encyclopædia Britannica.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Midelfort, H. C. Erik (1999). A History of Madness in Sixteenth-century Germany. Stanford University Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-8047-4169-9.

- Miller (2017), pp. 149–164

- Soth, Amelia (2019-01-10). "When Dancing Plagues Struck Medieval Europe". JSTOR Daily. Retrieved 2021-03-22.

- Gloyne, Howard F. (March 1950). "TARANTISM: Mass Hysterical Reaction to Spider Bite in the Middle Ages". American Imago. 7 (1): 29–42. ISSN 0065-860X. JSTOR 26301236. PMID 15413592.

- Waller J (February 2009). "A forgotten plague: making sense of dancing mania". Lancet. 373 (9664): 624–625. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60386-X. PMID 19238695. S2CID 35094677. Archived from the original on 2014-11-08. Retrieved 2016-04-08.

- Clementz, Élisabeth (2016). "Waller (John), Les danseurs fous de Strasbourg. Une épidémie de transe collective en 1518". Revue d'Alsace - Fédération des Sociétés d'Histoire et d'Archéologie d'Alsace. 142: 451–453.

- Miller (2017), p. 151: "Four of the six chronicle accounts also make this assertion that a solitary woman by the name of Lady Troffea began the plague."

- "The Witches Curse ~ Clues and Evidence | Secrets of the Dead | PBS". Secrets of the Dead. 2014-06-04. Retrieved 2021-03-22.

- Fessenden, Marissa. "A Strange Case of Dancing Mania Struck Germany Six Centuries Ago Today". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2021-03-22.

- Kaufman, David Myland; Milstein, Mark J. (2013). Kaufman's Clinical Neurology for Psychiatrists. Chapter 18: Involuntary Movement Disorders (Seventh ed.). Elsevier. pp. 397–453. ISBN 978-0-7234-3748-2.

- "Mystery explained? 'Dancing Plague' of 1518, the bizarre dance that killed dozens". 13 August 2008. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- Cardoso, Francisco; Seppi, Klaus; Mair, Katherina J; Wenning, Gregor K; Poewe, Werner (July 2006). "Seminar on choreas". The Lancet Neurology. 5 (7): 589–602. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70494-X. PMID 16781989. S2CID 41265524.

- Haq, Ihtsham U; Tate, Jessica A; Siddiqui, Mustafa S; Okun, Michael S (2017). Youmans and Winn Neurological Surgery: Clinical Overview of Movement Disorders (Seventh ed.). Elsevier. pp. 573–585.e7. ISBN 978-0-323-28782-1.

- Kaufman, David Myland; Geyer, Howard L; Milstein, Mark J (2017). Involuntary Movement Disorders (Eighth ed.). Elsevier. pp. 389–447. ISBN 978-0-323-46131-3.

Bibliography

- Miller, Lynneth (Winter 2017). "Divine Punishment or Disease? Medieval and Early Modern Approaches to the 1518 Strasbourg Dancing Plague". Dance Research. Edinburgh University Press. 35 (2): 149–164. doi:10.3366/drs.2017.0199. ISSN 0264-2875. JSTOR 90020124.

Further reading

- Backman, Eugene Louis (1977) [1952]. Religious Dances in the Christian Church and in Popular Medicine. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-8371-9678-7.

- Waller, John (2008). A Time to Dance, A Time to Die: The Extraordinary Story of the Dancing Plague of 1518. Thriplow: Icon Books. ISBN 978-1-84831-021-6.

- Waller, John (2009). The Dancing Plague: The Strange, True Story of an Extraordinary Illness. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4022-1943-6.

- Hecker, J. F. C. (Justus Friedrich Carl) (1888). Morley, Henry (ed.). The black death and the dancing mania. Translated by Babington, B. G. (Benjamin Guy). Woodruff Health Sciences Center Library Emory University. Cassell & Company. pp. 105–192. OCLC 00338041.

External links

- "Dancing death" by John Waller. BBC News. 12 September 2008.

- "Strasbourg 1518" (dance-theatre production) by Borderline Arts Ensemble. New Zealand Festival of the Arts. 12 March 2020.

- "Strasbourg 1518" (short film) by Jonathan Glazer. BBC. 20 July 2020.