Effects of stress on memory

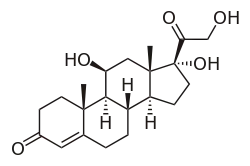

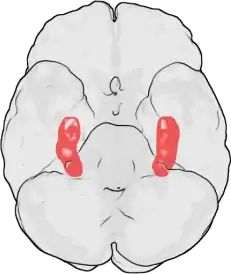

The effects of stress on memory include interference with a person's capacity to encode memory and the ability to retrieve information.[1][2] During times of stress, the body reacts by secreting stress hormones into the bloodstream. Stress can cause acute and chronic changes in certain brain areas which can cause long-term damage.[3] Over-secretion of stress hormones most frequently impairs long-term delayed recall memory, but can enhance short-term, immediate recall memory. This enhancement is particularly relative in emotional memory. In particular, the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex and the amygdala are affected.[4][5] One class of stress hormone responsible for negatively affecting long-term, delayed recall memory is the glucocorticoids (GCs), the most notable of which is cortisol.[1][5][6] Glucocorticoids facilitate and impair the actions of stress in the brain memory process.[7] Cortisol is a known biomarker for stress.[8] Under normal circumstances, the hippocampus regulates the production of cortisol through negative feedback because it has many receptors that are sensitive to these stress hormones. However, an excess of cortisol can impair the ability of the hippocampus to both encode and recall memories.[2] These stress hormones are also hindering the hippocampus from receiving enough energy by diverting glucose levels to surrounding muscles.[2]

Stress affects many memory functions and cognitive functioning of the brain.[9] There are different levels of stress and the high levels can be intrinsic or extrinsic. Intrinsic stress level is triggered by a cognitive challenge whereas extrinsic can be triggered by a condition not related to a cognitive task.[7] Intrinsic stress can be acutely and chronically experienced by a person.[7] The varying effects of stress on performance or stress hormones are often compared to or known as "inverted-u"[9] which induce areas in learning, memory and plasticity.[7] Chronic stress can affect the brain structure and cognition.

Studies considered the effects of both intrinsic and extrinsic stress on memory functions, using for both of them Pavlovian conditioning and spatial learning.[7] In regard to intrinsic memory functions, the study evaluated how stress affected memory functions that was triggered by a learning challenge. In regard to extrinsic stress, the study focused on stress that was not related to cognitive task but was elicited by other situations. The results determined that intrinsic stress was facilitated by memory consolidation process and extrinsic stress was determined to be heterogeneous in regard to memory consolidation. Researchers found that high stress conditions were a good representative of the effect that extrinsic stress can cause on memory functioning.[7] It was also proven that extrinsic stress does affect spatial learning whereas acute extrinsic stress does not.[7]

Physiology

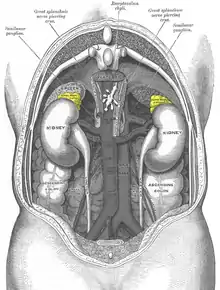

When a stressful situation is encountered, stress hormones are released into the blood stream. Adrenaline is released by the adrenal glands to begin the response in the body. Adrenaline acts as a catalyst for the fight-or-flight response,[10] which is a response of the sympathetic nervous system to encourage the body to react to the apparent stressor. This response causes an increase in heart-rate, blood pressure, and accelerated breathing. The kidneys release glucose, providing energy to combat or flee the stressor.[11] Blood is redirected to the brain and major muscle groups, diverted away from energy consuming bodily functions unrelated to survival at the present time.[10] There are three important axes, the adrenocorticotropic axis, the vasopressin axis and the thyroxine axis, which are responsible for the physiologic response to stress.

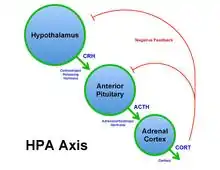

Adrenocorticotropic hormone axis

When a receptor within the body senses a stressor, a signal is sent to the anterior hypothalamus. At the reception of the signal, corticotrophin-releasing factor (CRF) acts on the anterior pituitary. The anterior pituitary in turn releases adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH).[12][13] ACTH induces the release of corticosteroids and aldosterone from the adrenal gland. These substances are the main factors responsible for the stress response in humans. Cortisol for example stimulates the mobilization of free fatty acids and proteins and the breakdown of amino acids, and increases serum glucose level and blood pressure,[11] among other effects.[14] On the other hand, aldosterone is responsible for water retention associated with stress. As a result of cells retaining sodium and eliminating potassium, water is retained and blood pressure is increased by increasing the blood volume.

Vasopressin axis

A second physiological response in relation to stress occurs via the vasopressin axis. Vasopressin, also known as antidiuretic hormone (ADH), is synthesized by the neurons in the supraoptic nucleus of the hypothalamus and regulates fluid loss by manipulating the urinary tract.[15] This pathway allows water reabsorption within the body and decreases the amount of water lost through perspiration. ADH has the greatest[greatest among what?] effect on blood pressure within the body. Under normal circumstances, ADH will regulate the blood pressure and increase or decrease the blood volume when needed.[11] However, when stress becomes chronic, homeostatic regulation of blood pressure is lost. Vasopressin is released and causes a static increase in blood pressure. This increase in blood pressure under stressful conditions ensures that muscles receive the oxygen that they need to be active and respond accordingly.[15] If these stressful conditions remain elevated, muscles will become fatigued, resulting in hypertension and in extreme cases can result in death.

Thyroxine axis

The third physiological response results in the release of thyrotropic hormone-release factor (TRF)[Where, when and how?] which results in the release of thyrotropic hormone (TTH).[16] TTH stimulates the release of thyroxine and triiodothyronine from the thyroid.[16] This results in an increased basal metabolic rate (BMR).[What effect does that have?] This effect is not as immediate as the other two, and can take days to weeks to become prevalent.

Chronic stress

Chronic stress is the response to emotional pressure suffered for a prolonged period of time in which an individual perceives they have little or no control.[17] When chronic stress is experienced, the body is in a state of continuous physiological arousal.[18] Normally, the body activates a fight-or-flight-response, and when the perceived stress is over the body returns to a state of homeostasis. When chronic stress is perceived, however, the body is in a continuous state of fight-or-flight response and never reaches a state of homeostasis. The physiological effects of chronic stress can negatively affect memory and learning.[18] One study used rats to show the effects of chronic stress on memory by exposing them to a cat for five weeks and being randomly assigned to a different group each day.[19] Their stress was measured in a naturalistic setting by observing their open field behaviour, and the effect on memory was estimated using the radial arm water maze (RAWM). In the RAWM, rats are taught the place of a platform that is placed below the surface of the water. They must recall this later to discover the platform to exit the water. It was found that the rats exposed to chronic psychosocial stress could not learn to adapt to new situations and environments, and had impaired memory on the RAWM.[19]

Chronic stress affects a person's cognitive functioning differently for typical subjects versus subjects with mild cognitive impairment.[20] Chronic stress and elevated cortisol (a biomarker for stress) has been known to lead to dementia in elderly people.[3] A longitudinal study was performed which included 61 cognitively typical people and 41 people with mild cognitive impairment. The participants were between 65 and 97 years old. 52 of the participants were followed for three years and repeatedly received stress and cognitive test assessments. Any patient with signs or conditions that would affect their cortisol level or cognitive functioning was exempt from participating.[8]

In general, higher event-based stress was associated with more rapid cognitive impairment. However, participants with greater cortisol levels showed signs of slower decline. Neither of these effects held for the non-cognitively-impaired group.[8]

Acute stress

Acute stress is a stressor that is an immediate perceived threat.[21] Unlike chronic stress, acute stress is not ongoing and the physiological arousal associated with acute stress is not nearly as demanding. There are mixed findings on the effects of acute stress on memory. One view is that acute stress can impair memory, while others believe that acute stress can actually enhance memory.[22][23] Several studies have shown that stress and glucocorticoids enhance memory formation while they impair memory retrieval.[24] For acute stress to enhance memory certain circumstances must be met. First, the context in which the stress is being perceived must match the context of the information or material being encoded.[25] Second, the brain regions involved in the retrieval of the memory must match the regions targeted by glucocorticoids.[25] There are also differences in the type of information being remembered or being forgotten while being exposed to acute stress. In some cases neutral stimuli tend to be remembered, while emotionally charged (salient) stimuli tend to be forgotten. In other cases the opposite effect is obtained.[26] What seems to be an important factor in determining what will be impaired and what will be enhanced is the timing of the perceived stressful exposure and the timing of the retrieval.[25] For emotionally salient information to be remembered, the perceived stress must be induced before encoding, and retrieval must follow shortly afterwards.[25] In contrast, for emotionally charged stimuli to be forgotten, the stressful exposure must be after encoding and retrieval must follow after a longer delay.[25]

If stressful information is relatable to a person, the event more prone to be stored in permanent memory. When a person is under stress, the sympathetic system will shift to a constantly (tonically) active state. To further study how acute stress affect memory formation, a study would appropriate to add examine.[4] Acute stress exposure induces the activation of different hormonal and neurotransmitters which effect the memory's working processes.[27]

A study published in 2009 tested eighteen young healthy males between 19 and 31 years old. All participants were right-handed and had no history of a head injury, or of any medication that could affect a person central nervous system or endocrine system. All of the volunteers participated in two different sessions a month apart. The study consisted on the participants viewing movie clips and pictures that belonged to two different categories: neutral or negative. The participants had to memorize then rate each movie clip or picture by pressing a button with their right hand. They were also monitored in other areas such as their heart rate, pupil diameter, and stress measures by collection of saliva throughout the experiment. The participants mood was assessed by using the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule.[28]

The results from the study confirmed that there were physiological measures in regard to stress induction. The participant's heart rate was elevated and pupil dilation was decreased when viewing the pictures. The study also showed psychological measures that proved that stress induction did cause an increase in subjective stress. In regard to memory enhancement, participants that were shown a stressful picture, often remembered them a day later, which is in accordance with the theory that negative incidents have lasting effects on our memory.[28]

Acute stress can also affect a person's neural correlates which interfere with the memory formation. During a stressful time, a person's attention and emotional state may be affected, which could hinder the ability to focus while processing an image. Stress can also enhance the neural state of memory formation.[28]

Short-term memory

Short-term memory (STM), similar to Working Memory, is defined as a memory mechanism that can hold a limited amount of information for a brief period of time, usually around thirty seconds.[17] Stress, which is often perceived as only having negative effects, can aid in memory formation.[29] One example is how stress can benefit memory during encoding. Encoding is the time that memories are formed. An example of this was when researchers found that stress experienced during crimes improved eyewitness memory, especially under the influence of Repeat Testing.[30][25]

Miller's Law states that the capacity of an average person's STM is 7±2 objects, and lasts for a matter of seconds.[31] This means that when given a series of items to remember, most people can remember 5-9 of those items. The average is 7. However, this limit can be increased by rehearsing the information. Information in STM can be transferred to long-term memory (LTM) by rehearsal and association with other information previously stored in LTM. Most of the research on stress and memory has been done on working memory and the processing and storage that occurs rather STM.

Working memory

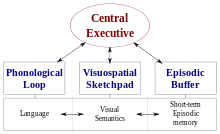

Working memory (WM), similar to STM, is the ability to temporarily store information in order to manipulate it for performing complex tasks, such as reasoning. WM is affected to a greater extent by stress than Long-term memory.[32] Stress has been shown to both improve and impair WM. In a study by Duncko et al., the positive effect of stress manifested itself as a decreased reaction time in participants, while the negative effect of stress causes more false alarms and mistakes when compared to a normal condition.[33] The researchers hypothesize that this could be representative of faster information processing, something helpful in a threatening situation. Anxiety has also been shown to adversely affect some of the components of WM, those being the phonological loop, the visuo-spatial sketchpad, and the central executive.[34] The phonological loop is used for auditory STM, the visuo-spatial sketchpad is used for visual and spatial STM, and the central executive links and controls these systems.[31] The disruption of these components impairs the transfer of information from WM to LTM, thus affecting learning. For instance, several studies have demonstrated that acute stress can impair working memory processing likely though reduced neural activity in the prefrontal cortex in both monkeys and humans.[35]

Long-term memory

Long-term memory (LTM) is a memory mechanism that can hold large amounts of information for long periods of time.[17]

Less is known about the effect of stress on LTM than is known about the effect of stress on STM. This could be due to the fact that LTM is not affected as severely as STM and WM are, and is also influenced by the effect of stress on STM and WM.[32]

The major effect of stress on LTM is that it improves consolidation of memory, while it impairs the retrieval of memory.[1][6][24] That is, one will be able to remember information relating to a stressful situation after the fact, but while in a stressful situation it is hard to recall specific information. In a study by Park et al. done on rats, the researchers found that shock induced stress caused the rats to forget what they learned in the phase prior to the shock, but to have distinct memory for where the shock occurred.[36] This negative effect on the retrieval of memories caused by stress can be attributed to cortisol, the stress hormone that is released in stressful situations. A study by Marin et al. demonstrated that stress enhances recall of information reviewed prior to the stressful situation, and that this effect is long lasting.[37]

Explicit memory

Explicit memory, or declarative memory, is the intentional recall of past events or learned information and is a discipline of LTM.[31] Explicit memory includes memory for remembering a specific event, such as dinner the week prior, or information about the world, such as the definition for explicit memory. When an anxious state is provoked, percentage recall on explicit memory tasks is enhanced. However, this effect is only present for emotionally associated words.[38] Stress hormones influence the processes carried out in the hippocampus and amygdala which are also associated with emotional responses.[38] Thus, emotional memories are enhanced when stress is induced, as they are both associated with the same areas of the brain, whereas neutral stimuli and stress are not. However, enhancement of explicit memory depends on the time of day.[38] Explicit memory is enhanced by stress when assessed in the afternoon, but impaired when assessed in the morning.[38] Basal cortisol levels are relatively low in the afternoon and much higher in the morning, which can alter the interaction and effects of stress hormones.[38]

Implicit memory

Implicit memory, or more precisely procedural memory, is memory of information without conscious awareness or ability to verbalize the process, and is also a discipline of LTM.[31] There are three types of implicit memory, which are: conditioning (emotional behavior), tasks and priming (verbal behavior).[39] For example, the process of riding a bicycle cannot be verbalized, but the action can still be executed. When implicit memory is assessed in tandem with stressful cues there is no change in procedural recall.[38]

Autobiographical memory

Autobiographical memory is personal episodic memory of self-related information and specific events.[31] Stress tends to impair the accuracy of autobiographical memories, but does not impair the frequency or confidence in them.[40] After exposure to an emotional and stressful negative event, flashback memories can be evident.[40] However, the more flashback memories present, the less accurate the autobiographical memory.[40] Both aspects of autobiographical memory, episodic memory, the memory system regarding specific events, and semantic memory, the memory system regarding general information about the world, are impaired by an event that induces a stressful response.[40] This causes the recall of an experience of a specific event and the information about the event to be recalled less accurately.[40]

Autobiographical memory, however, is not impaired on a continual decline from the first recall of the information when anxiety is induced.[41] At first recall attempt, the memory is fairly accurate.[41] The impairment begins when reconsolidation is present,[41] such that the more times the memory is brought to conscious awareness, the less accurate it will become. When stress is induced the memory will be susceptible to other influences,[41] such as suggestions from other people, or emotions unrelated to the event but present during recall. Therefore, stress at the encoding of an event positively influences memory, but stress at the time of recollection impairs memory.

Attention

Attention is the process by which a concentration is focused on a point of interest, such as an event or physical stimulus. It is theorized that attention toward a stimulus will increase ability to recall information, therefore enhancing memory.[42] When threatening information or a stimulus that provokes anxiety are present, it is difficult to release attention from the negative cue.[42] When in a state of high anxiety, a conceptual memory bias is produced toward the negative stimulus.[42][43] Therefore, it is difficult to redirect the attention focus away from the negative, anxiety provoking cue.[43] This increases the activation of the pathways associated with the threatening cues, and thus increases the ability to recall the information present while in a high anxious state.[42] However, when in a high anxious state and presented with positive information, there is no memory bias produced.[42] This occurs because it is not as difficult to redirect attention from the positive stimulus as it is from the negative stimulus. This is due to the fact that the negative cue is perceived as a factor in the induced stress, whereas the positive cue is not.[42]

Learning

Learning is the acquisition of knowledge or skills through experience, study, or by being taught and is the modification of behaviour by experience.[44] For example, learning to avoid certain stimuli such as a tornadoes, thunderstorms, large animals, and toxic chemicals, because they can be harmful. This is classified as aversion conditioning, and is related to fear responses.[45]

Fear response

The fear response arises from the perception of danger leading to confrontation with or escape from/avoiding the threat. An anxious state at the time of learning can create a stronger aversion to the stimuli.[46] A stronger aversion can lead to stronger associations in memory between the stimulus and response, therefore enhancing the memory of the response to the stimulus.[45] When extinction is attempted in male and female humans, compared to a neutral control without anxiety, extinction does not occur.[45] This suggests that memory is enhanced for learning, specifically fear learning, when anxiety is present.

Reversal learning

Conversely, reversal learning[What is it?] is inhibited by the presence of anxiety.[47][48] Reversal learning is assessed through the reversal learning task; a stimulus and response relationship is learned through the trial and error method and then without notice, the relationship is reversed, examining the role of cognitive flexibility.[47] Inhibited reversal learning can be associated with the idea that subjects experiencing symptoms of anxiety frustrate easily and are unable to successfully adapt to a changing environment.[48] Thus, anxiety can negatively affect learning when the stimulus and response relationship are reversed or altered.

Stress, memory and animals

Much of the research relating to stress and memory has been conducted on animals and can be generalized to humans.[49] One type of stress that is not easily translatable to humans is predator stress: the anxiety an animal experiences when in the presence of a predator.[50] In studies, stress is induced by introducing a predator to a subject either before the learning phase or between the learning phase and the testing phase. Memory is measured by various tests, such as the radial arm water maze (RAWM). In the RAWM, rats are taught the location of a hidden platform and must recall this information later on to find the platform and get out of the water.

Short-term memory

Other studies have suggested stress can decrease memory function. For instance, Predator Stress has been shown to impair STM.[36] It has been determined that this effect on STM is not due to the fact that a predator is a novel and arousing stimulus, but rather because of the fear that is provoked in the test subjects by the predators.[51]

Long-term memory

Predator stress has been shown to increase LTM. In a study done by Sundata et al. on snails, it was shown that when trained in the presence of a predator, snails' memory persisted for at least 24 hours in adults, while it usually lasts only 3 hours. Juvenile snails, who usually do not have any LTM showed signs of LTM after exposure to a predator.[52]

Classical conditioning

Predator stress has been shown to improve classical conditioning in males and hinder it in females. A study done by Maeng et al. demonstrated that stress allowed faster classical conditioning of male rats while disrupting the same type of learning in female rats.[53] These gender differences were shown to be caused by the Medial Prefrontal Cortex (mPFC). When the researchers inactivated that brain region by administering Muscimol to the females, no gender differences in classical conditioning were observed 24 hours later.[53] Inactivating the mPFC in the male rats did not prevent the enhanced conditioning that the males previously exhibited.[53] This discrepancy between genders has also been shown to be present in humans. In a 2005 study, Jackson et al. reported that stress enhanced classical conditioning in human males and impaired classical condition in human females.[54]

Anxiety disorders

Post-traumatic stress disorder

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is an anxiety disorder that can occur after exposure to horrific events, or after a terrifying ordeal where there is immense physical harm that directly or indirectly affects a person.[55] When the memories of these traumas do not subside, a person may begin to avoid anything that would cause them to relive these events. When this persists over an extended period of time, one may be said to be suffering from PTSD. Examples of events that could lead to the onset of PTSD are war, rape, assault, and childhood neglect.[56][57] It is estimated that approximately 8% of Americans may have this disease which can lead to long-term problems.[58]

Symptoms include persistent frightened thoughts and memories of the trauma or ordeal and emotional numbness.[55] The individual may experience sleeping problems, be easily startled, or experience feelings of detachment or numbness. Sufferers may experience depression and/or display self-destructive behaviours.

There are three categories of symptoms associated with PTSD:[56]

- Re-living the event: Through recurring nightmares or images that bring back memories of the events. When people re-live the event they become panicked, and they may have physical and emotional chills or heart palpitations.

- Avoiding reminders: Avoiding reminders of the events, including places, people, thoughts or other activities relating to the specific event. Withdrawal from family and friends and loss of interest in activities may occur from PTSD

- Being on guard: Symptoms also include an inability to relax, feelings of irritability or sudden anger, sleeping problems, and being easily startled.

The most effective treatments for PTSD are psychotherapy, medication, and in some circumstance both.[57] Effective psychotherapy involves helping the individual with managing the symptoms, coping with the traumatic event, and working through the traumatic experiences. Medications such as antidepressants has proven to be an effective way to block the effects of stress and to also promote neurogenesis.[7] The medication phenytoin can also block stress caused to the hippocampus with the help of modulation of excitatory amino acids.[58] Preliminary findings indicate that cortisol may be helpful to reduce traumatic memory in PTSD.[59]

PTSD affects memory recall and accuracy.[40] The more the traumatic event is brought to conscious awareness and recalled, the less accurate the memory.[40] PTSD affects the verbal memory of the traumatic event, but does not affect the memory in general.[40] One of the ways traumatic stress affects individuals is that the traumatic event tends to disrupt the stream of memories people obtain through life, creating memories that do not blend in with the rest. This has the effect of creating a split in identity as the person now has good memories they can attribute to one personality and bad memories the can attribute to the "other" personality. For example, a victim of childhood abuse can group their good and happy experiences under the "pleasant" personality and their abuse experiences under one "bad or wicked" personality. This then creates a split personality disorder.[60] Individuals with post traumatic stress disorder often have difficulty remembering facts, appointments and autobiographical details.[61] The traumatic event can result in psychogenic amnesia and in the occurrence of intrusive recollections of the event. Children with PTSD have deficits in cognitive processes essential for learning; their memory systems also under-performs those of normal children. A study using the Rivermead Behavioural Memory Test showed that individuals with PTSD scored lower than controls on the memory test, indicating a poorer general knowledge. The study revealed that 78% of PTSD patients under-performed, and where in the categories labelled "poor memory" or "impaired memory".[61] PTSD patients were specifically worse at the prospective and orientation items on the Rivermead Behavioural Memory Test.

A few studies done in the past proved that PTSD can cause cognition and brain structure changes that involve verbal declarative memory deficits. Children that have experienced child abuse may according to neuropsychological testing experience a deficit in verbal declarative memory functioning.[58]

Studies have been conducted on people that were involved in the Vietnam War or the Holocaust, returning Iraq soldiers and people that also suffered from rape and childhood abuse. Different tests were administered such as the Selective Reminding Test, Verbal Learning Test, Paired Associate Recall, the California Verbal New Learning Test, and the Rivermead Behavioral Memory Test.[58] The test results showed that the returning Iraq soldiers did have less verbal memory performance as compared to pre-deployment.[58]

The studies performed on the Vietnam veterans that suffer from PTSD show that there are hippocampal changes in the brain associated with this disorder. The veterans with PTSD showed an 8% reduction in their right hippocampal volume. The patients that suffered from child abuse showed a 12% reduction in their mean left hippocampal volume.[58] Several of the studies has also shown that people with PTSD have deficits while performing verbal declarative memory task in their hippicampal.[58]

PTSD can affect several parts of the brain such as the amygdala, hippocampus, and the prefrontal cortex. The amygdala controls our memory and emotional processing; the hippocampus helps with organizing, storing and memory forming. Hippocampus is the most sensitive area to stress.[58] The prefrontal cortex helps with our expression and personality and helps regulate complex cognitive and our behavior functions.

Social anxiety disorder

Social anxiety disorder is an anxiety disorder consisting of overwhelming anxiety and excessive self-consciousness in everyday social situations.[62] It is an extreme fear of being scrutinized and judged by others in social and/or performance situations. This fear about a situation can become so severe that it affects work, school, and other typical activities.[63] Social anxiety can be related to one situation (such as talking to people) or it can be much more broad, where a person experiences anxiety around everyone except family members.

People with social anxiety disorder have a constant, chronic fear of being watched and judged by peers and strangers, and of doing something that will embarrass them. People with this may physically feel sick from the situation, even when the situation is non-threatening.[63] Physical symptoms of the disorder include blushing, profuse sweating, trembling, nausea or abdominal distress, rapid heartbeat, shortness of breath, dizziness or lightheadedness, headaches, and feelings of detachment. Development of low self-esteem, poor social skills, and trouble being assertive are also common signs of social anxiety disorder.[64]

Social anxiety disorder can be treated with many different types of therapy and medication. Exposure therapy is an effective method of treating social anxiety. In exposure therapy a patient is presented with situations that they are afraid of, gradually building up to facing the situation that the patient fears most.[64] This type of therapy helps the patient learn new techniques to cope with different situations that they fear. Role-playing has proven effective for the treatment or social anxiety. Role-playing therapy helps to boost individuals' confidence relating to other people and helps increase social skills. Medication is another effective method for treating social anxiety. Antidepressants, beta blockers, and anti-anxiety medications are the most commonly prescribed types of medication to treat social anxiety.[64] Moreover, there are new approaches to treat phobias and enhance exposure therapy with glucocorticoids.[65][66]

Social phobics display a tendency to recall negative emotions about a situation when asked to recall the event.[67] Their emotions typically revolve around themselves, with no recollection of other people's environments. Social anxiety results in negative aspects of the event to be remembered, leading to a biased opinion of the situation from the perspective of the social phobic compared to the non-social phobic.[67] Social phobics typically displayed better recall than control participants. However, individuals with social anxiety recalled angry faces rather than happy or neutral faces better than control participants.[68]

Obsessive-compulsive disorder

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) involves both obsessions and compulsions that disrupt daily routines and activities.[69] The obsessions include recurrent unwanted thoughts that cause compulsions, including repetitive behaviors.[70] Individuals with OCD may realize that their obsessions are not normal and try to stop their actions, but this only increases the person's anxiety towards the situation, and has an adverse effect. OCD often revolves around themes in one's life; for example, fear of coming in contact with germs (obsession).[69] To deal with the fear of germs one may compulsively wash their hands until they are chapped. OCD is a constituent of many other disorders including autism, Tourette's syndrome, and frontal lobe lesions.[71]

A person that shows a constant need to complete a certain "ritual", or is constantly plagued with unwelcome thoughts, may suffer from OCD. Themes of obsessions include fear of germs or dirt, having things orderly and symmetrical, and sexual thoughts and images. Signs of obsessions:[70]

- fear of being contaminated which leads to avoidance of shaking hands with others, or touching items others have touched;

- doubts that you've completed tasks such as locking doors or turning appliances off;

- skin conditions due to excessive washing of one's hands;

- stress when items are not orderly or neat;

- thoughts about shouting obscenities or acting inappropriately;

- replaying pornographic images in one's head;

Compulsions follow the theme of the obsessions, and are repetitive behaviors that individuals with OCD feel will diminish the effect of the obsession.[70] Compulsions also follow the theme, including hand washing, cleaning, performing actions repeatedly, or extreme orderliness.

Signs of compulsions:[70]

- washing hands until skin is damaged;

- counting in certain patterns;

- silently repeating a prayer, word or phrase;

- arranging food items so that everything faces the same way;

- checking locks repeatedly to make sure everything is locked;

Behavior therapy has proven to be an effective method for treating OCD.[72] Patients are exposed to the theme that is typically avoided, while being restricted from performing their usual anxiety reducing rituals. Behavior therapy rarely eliminates OCD, but it helps to reduce the signs and symptoms. With medication, this reduction of the disorder is even more evident. Antidepressants are usually the first prescribed medication to a patient with OCD. Medications that treat OCD typically inhibit the reuptake of serotonin.[72]

Obsessive-compulsive individuals have difficulty forgetting unwanted thoughts.[73] When they encode this information into memory they encode it as a neutral or positive thought. This is inconsistent with what a person without OCD would think about this thought, leading the individual with OCD to continue displaying their specific "ritual" to help deal with their anxiety. When asked to forget information they have encoded, OCD patients have difficulty forgetting what they are told to forget only when the subject is negative.[73] Individuals not affected by OCD do not show this tendency. Researchers have proposed a general deficit hypothesis for memory related problems in OCD.[74] There are limited studies investigating this hypothesis. These studies propose that memory is enhanced for menacing events that have occurred during the individuals life. For example, a study demonstrated that individuals with OCD exhibit exceptional recall for previously encountered events, but only when the event promoted anxiety in the individual.

References

- de Quervain et al., Stress and glucocorticoids impair retrieval of long-term spatial memory. Nature, 394, 787-790 (1998)

- Kuhlmann, S.; Piel, M.; Wolf, O.T. (2005). "Impaired Memory Retrieval after Psychosocial Stress in Healthy Young Men". Journal of Neuroscience. 25 (11): 2977–2982. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.5139-04.2005. PMC 6725125. PMID 15772357.

- Henckens, M. J. A. G.; Hermans, E. J.; Pu, Z.; Joels, M.; Fernandez, G. (12 August 2009). "Stressed Memories: How Acute Stress Affects Memory Formation in Humans". Journal of Neuroscience. 29 (32): 10111–10119. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1184-09.2009. PMC 6664979. PMID 19675245.

- Henckens, M. J. A. G.; Hermans, E. J.; Pu, Z.; Joels, M.; Fernandez, G. (12 August 2009). "Stressed Memories: How Acute Stress Affects Memory Formation in Humans". Journal of Neuroscience. 29 (32): 10111–10119. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.1184-09.2009. PMC 6664979. PMID 19675245.

- Oei, N.Y.L.; Elzinga, B.M.; Wolf, O.T.; de Ruiter, M.B.; Damoiseaux, J.S.; Kuijer, J.P.A.; Veltman, D.J.; Scheltens, P.; Rombouts, S.A.R.B. (2007). "Glucocorticoids Decrease Hippocampal and Prefrontal Activation during Declarative Memory Retrieval in Young Men". Brain Imaging and Behaviour. 1 (1–2): 31–41. doi:10.1007/s11682-007-9003-2. PMC 2780685. PMID 19946603.

- de Quervain et al., Acute cortisone administration impairs retrieval of long-term declarative memory in humans. Nature Neuroscience, 3, 313-314 (2000)

- Sandi, Carmen; Pinelo-Nava, M. Teresa (1 January 2007). "Stress and Memory: Behavioral Effects and Neurobiological Mechanisms". Neural Plasticity. 2007: 78970. doi:10.1155/2007/78970. PMC 1950232. PMID 18060012.

- Peavy, G. M.; Salmon, D. P.; Jacobson, M. W.; Hervey, A.; Gamst, A. C.; Wolfson, T.; Patterson, T. L.; Goldman, S.; Mills, P. J.; Khandrika, S.; Galasko, D. (15 September 2009). "Effects of Chronic Stress on Memory Decline in Cognitively Normal and Mildly Impaired Older Adults". American Journal of Psychiatry. 166 (12): 1384–1391. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09040461. PMC 2864084. PMID 19755573.

- Cavanagh, J. F.; Frank, M. J.; Allen, J. J. B. (7 May 2010). "Social stress reactivity alters reward and punishment learning". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 6 (3): 311–320. doi:10.1093/scan/nsq041. PMC 3110431. PMID 20453038.

- Pendick, D. (2002). Memory loss and the brain. Retrieved from http://www.memorylossonline.com/spring2002/stress.htm

- Ziegler, D; Herman, J (2002). "Neurocircuitry of stress integration: anatomical pathways regulating the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical axis of the rat". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 42 (3): 541–551. doi:10.1093/icb/42.3.541. PMID 21708749.

- Viau, V.; Soriano, L.; Dallman, M (2001). "Androgens alter corticotropin releasing hormone and arginine vasopressin mrna within forebrain sites known to regulate activity in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis". Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 13 (5): 442–452. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2826.2001.00653.x. PMID 11328455. S2CID 12418309.

- Antoni F. Hypothalamic control of adrenocorticotropin secretion: advances since the discovery of 41-residue corticotropin-releasing factor" Endo Rev 1986; 7: 351 – 378.

- Talbott, S. (2007). The cortisol connection. Alameda, CA: Hunter House Inc.

- Scott, L; Dinan, T (1998). "Vasopressin and the regulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function: implications for the pathophysiology of depression". Life Sciences. 62 (22): 1985–1998. doi:10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00027-7. PMID 9627097.

- Prange, A (1999). "Thyroid axis sustaining hypothesis of posttraumatic stress disorder". Psychosomatic Medicine. 61 (2): 139–140. doi:10.1097/00006842-199903000-00002. PMID 10204963.

- Goldstein, E.B. (2015). Cognitive Psychology: connecting mind, research, and everyday experience. Boston, MA, USA: Cengage Learning Inc. ISBN 978-1337408271.

- Pasquali, R (2006). "The Biological Balance between Psychological Well-Being and Distress: A Clinician's Point of View". Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 75 (2): 69–71. doi:10.1159/000090890. PMID 16508341.

- Parkad, C.R.; Campbella, A.M.; Diamond, D.M. (2001). "Chronic psychosocial stress impairs learning and memory and increases sensitivity to yohimbine in adult rats". Biological Psychology. 50 (12): 994–1004. doi:10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01255-0. PMID 11750896. S2CID 36350625.

- Peavy, G. M.; Salmon, D. P.; Jacobson, M. W.; Hervey, A.; Gamst, A. C.; Wolfson, T.; Patterson, T. L.; Goldman, S.; Mills, P. J.; Khandrika, S.; Galasko, D. (2009). "Effects of chronic stress on memory decline in cognitively normal and mildly impaired older adults". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 166 (12): 1384–91. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09040461. PMC 2864084. PMID 19755573.

- Neupert, S.D.; Almeida, D.M.; Mroczek, D.K.; Spiro, A. (2006). "Daily Stressors and Memory Failure in a Naturalistic Setting: Findings from the VA Normative Aging Study". Psychology and Aging. 21 (2): 424–429. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.21.2.424. PMID 16768588. S2CID 17918449.

- Yuen, E. Y.; Liu, W.; Karatsoreos, I. N.; Feng, J.; McEwen, B. S.; Yan, Z. (2009-07-29). "Acute stress enhances glutamatergic transmission in prefrontal cortex and facilitates working memory". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (33): 14075–14079. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10614075Y. doi:10.1073/pnas.0906791106. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 2729022. PMID 19666502.

- Cahill, L. (July 2003). "Enhanced human memory consolidation with post-learning stress: Interaction with the degree of arousal at encoding". Learning & Memory. 10 (4): 270–274. doi:10.1101/lm.62403. PMC 202317. PMID 12888545.

- Quervain, De; et al. (2009). "Glucocorticoids and the regulation of memory in health and disease". Front Neuroendocrinol. 30 (3): 358–70. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2009.03.002. PMID 19341764. S2CID 15832567.

- Smeets, T.; Giesbrecht, T.; Jelicic, M.; Merckelbach, H. (2007). "Context-dependent enhancement of declarative memory performance following acute psychosocial stress". Biological Psychology. 76 (1–2): 116–123. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2007.07.001. PMID 17689852. S2CID 668685.

- Jelicic, M.; Geraerts, E.; Merckelbach, H.; Guerrieri, R. (2004). "Acute Stress Enhances Memory For Emotional Words, But Impairs Memory For Neutral Words". International Journal of Neuroscience. 114 (10): 1343–1351. doi:10.1080/00207450490476101. PMID 15370191. S2CID 30184521.

- Roozendaal B, McEwen BS, Chattarji S (June 2009). "Stress, memory and the amygdala". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 10 (6): 423–33. doi:10.1038/nrn2651. PMID 19469026. S2CID 205505010.

- Henckens, M. J. A. G.; Hermans, E. J.; Pu, Z.; Joëls, M.; Fernández, G. (2009). "Stressed Memories: How Acute Stress Affects Memory Formation in Humans". Journal of Neuroscience. 29 (32): 10111–10119. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1184-09.2009. PMC 6664979. PMID 19675245.

- "Short-term Stress Can Affect Learning And Memory". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- "Emotional Stress and Eyewitness Memory: A Critical Review". PsycNET.

- Baddeley, A., Eysenck, M. W. & Anderson, M. C. (2010). Memory. Psychology Press: New York.

- O'Hare, D. (1999). Human performance in general aviation. Aldershot, England: Ashgate.

- Duncko, R.; Johnson, L.; Merikangas, K.; Grillon, C. (2009). "Working memory performance after acute exposure to the cold pressor stress in healthy volunteers". Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 91 (4): 377–381. doi:10.1016/j.nlm.2009.01.006. PMC 2696884. PMID 19340949.

- Lee, J. H. (1999). "Test anxiety and working memory". Journal of Experimental Education. 67 (3): 218–225. doi:10.1080/00220979909598354.

- Qin, S; Cousijn, H; Rijpkema, M; Luo, J; Franke, B; Hermans, E. J.; Fernández, G (2009). "The effect of moderate acute psychological stress on working memory-related neural activity is modulated by a genetic variation in catecholaminergic function in humans". Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience. 6: 16. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.368.5822. doi:10.3389/fnint.2012.00016. PMC 3350069. PMID 22593737.

- Park, C. R.; Zoladz, P. R.; Conrad, C. D.; Fleshner, M.; Diamond, D.M. (2008). "Acute predator stress impairs the consolidation and retrieval of hippocampus-dependent memory in male and female rats". Learning and Memory. 15 (4): 271–280. doi:10.1101/lm.721108. PMC 2327269. PMID 18391188.

- Marin, M.; Pilgrim, K.; Lupien, S. J. (2010). "Modulatory effects of stress on reactivated emotional memories". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 35 (9): 1388–1396. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.04.002. PMID 20471179. S2CID 27547727.

- Schwabe, Lars; Römer, Sonja; Richter, Steffen; Dockendorf, Svenja; Bilak, Boris; Schächinger, Hartmut (2009). "Stress effects on declarative memory retrieval are blocked by a β-adrenoceptor antagonist in humans" (PDF). Psychoneuroendocrinology. 34 (3): 446–454. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.10.009. PMID 19028019. S2CID 11695727.

- Bremner, J.D.; Krystal, J.H; Southwick, S.M.; Charney, D.S. (1995). "Functional neuroanatomical correlates of the effects of stress on memory". Journal of Traumatic Stress. 8 (4): 527–553. doi:10.1007/bf02102888. PMID 8564272. S2CID 38165362.

- Moradi, A. R., Herlihy, J., Yasseri, G., Shahraray, M., Turner, S. & Dalgleish, T. (2008). Specifically of episodic memory and semantic memory aspects of autobiographical memory in relation to symptoms of post traumatic stress disorder. Science Direct: 127, 645-653.

- Schwabe, Lars; Wolf, Oliver T. (2010). "Stress impairs the reconsolidation of autobiographical memories". Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 94 (2): 153–157. doi:10.1016/j.nlm.2010.05.001. PMID 20472089. S2CID 38684268.

- Daleiden, L (1998). "Childhood anxiety and memory functioning: a comparison of systematic and processing accounts". Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 68 (3): 216–235. doi:10.1006/jecp.1997.2429. PMID 9514771. S2CID 7757205.

- Derryberry, D.; Reed, M. A. (1994). "Temperament and attention: Orienting toward and away from positive and negative signals". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 66 (6): 1128–1130. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.66.6.1128. PMID 8046580.

- Gaulin, S. J. C. & McBurney, D. H. (2004). Evolutionary Psychology. Pearson: New Jersey, 2.

- Vriends, N.; Michael, T.; Blechert, J.; Meyer, A.H.; Marhraf, J.; Wilhelm, F. H. (2011). "The influence of state anxiety on the acquisition and extinction of fear". Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 42 (1): 46–53. doi:10.1016/j.jbtep.2010.09.001. PMID 21074006.

- Zinbarg, R. E.; Mohlman, J. (1998). "Individual differences in the acquisition of affectivity valenced associations". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 74 (4): 1024–1040. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.4.1024. PMID 9569657.

- Dickstein, D.P.; Finger, E.C.; Brotman, B.A.; Rich, D.S.; Blair, J.R.; Leibenloft, E.L. (2010). "Impaired probabilistic reversal learning in youths with mood and anxiety disorders". Psychological Medicine. 40 (7): 1089–1100. doi:10.1017/s0033291709991462. PMC 3000432. PMID 19818204.

- Blair, R.J.; Cipolotti, L. (2000). "Impaired social responses. A case of sociopathy". Brain. 123 (6): 1122–1141. doi:10.1093/brain/123.6.1122. PMID 10825352.

- Hitch, G. J. (1985). Short-term memory and information processing in humans and animals: Towards an integrative framework. In L.-G. Nilsson & T. Archer (Eds.), Series in comparative cognition and neuroscience. Perspectives on learning and memory (p. 119–136). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Figueiredo, Helmer F.; Bodie, Bryan L.; Tauchi, Miyuki; Dolgas, C. Mark; Herman, James P. (2003-12-01). "Stress Integration after Acute and Chronic Predator Stress: Differential Activation of Central Stress Circuitry and Sensitization of the Hypothalamo-Pituitary-Adrenocortical Axis". Endocrinology. 144 (12): 5249–5258. doi:10.1210/en.2003-0713. ISSN 0013-7227. PMID 12960031.

- Woodson, J. C.; Macintosh, D.; Flesner, M.; Diamond, D. M. (2003). "Emotion-Induced Amnesia in Rats: Working Memory-Specific Impairment, Corticosterone-Memory Correlation, and Fear Versus Arousal Effects on Memory". Learning and Memory. 10 (5): 326–336. doi:10.1101/lm.62903. PMC 217998. PMID 14557605.

- Sundada, H.; Horikoshi, T.; Lukawiak, K.; Sakakibara, M. (2010). "Increase in excitability of RPeD11 results in memory enhancement of juvenile and adult Lymnaea stagnalis by predator-induced stress". Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 94 (2): 269–277. doi:10.1016/j.nlm.2010.06.005. PMID 20601028. S2CID 24387482.

- Maeng, L. Y.; Waddell, J.; Shors, T. J. (2010). "The Prefrontal Cortex Communicates with the Amygdala to Impair Learning after Acute Stress in Females but Not in Males". The Journal of Neuroscience. 30 (48): 16188–16196. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.2265-10.2010. PMC 3073607. PMID 21123565.

- Jackson, E.D.; Payne, J.D.; Nadel, L.; Jacobs, W.J. (2005). "Stress differentially modulates fear conditioning in healthy men and women". Biological Psychiatry. 59 (6): 516–522. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.08.002. PMID 16213468. S2CID 11699080.

- National Institute of Mental Health, . (2011). Post-traumatic stress disorder (ptsd). Retrieved from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/post-traumatic-stress-disorder-ptsd/index.shtml

- PTSD Alliance, Initials. (2001). Post traumatic stress disorder. Retrieved from http://www.ptsdalliance.org/about_symp.html

- Mayo Clinic Staff, . (2009). Post-traumatic stress disorder (ptsd) . Retrieved from http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/post-traumatic-stress-disorder/DS00246

- Bremner, J. Douglas (1 November 2007). "Neuroimaging in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Other Stress-Related Disorders". Neuroimaging Clinics of North America. 17 (4): 523–538. doi:10.1016/J.NIC.2007.07.003. PMC 2729089. PMID 17983968.

- Aerni, A; Traber, R; Hock, C; Roozendaal, B; Schelling, G; Papassotiropoulos, A; Nitsch, RM; Schnyder, U; de Quervain, DJ (2004). "Low-dose cortisol for symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder". Am J Psychiatry. 161 (8): 1488–90. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1488. PMID 15285979. S2CID 7612028.

- Bremner, J. Douglas; Krystal, John H.; Southwick, Steven M.; Charney, Dennis S. (1995). "Functional Neuroanatomical Correlates of the Effects of Stress on Memory". Journal of Traumatic Stress. 8 (4): 527–553. doi:10.1007/bf02102888. PMID 8564272. S2CID 38165362.

- Moradi, A. R.; Doost, H. T. N.; Taghavi, M. R.; Yule, W.; Dalgleish, T. (1999). "Everyday memory deficits in children and adolescents with ptsd: performance on the rivermead behavioural memory test". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 40 (3): 357–361. doi:10.1111/1469-7610.00453. PMID 10190337.

- National Institute of Mental Health, . (2011). Social phobia (social anxiety disorder). Retrieved from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/social-phobia-social-anxiety-disorder/index.shtml

- Anxiety disorders association of america, Initials. (2010). Social anxiety disorder. Retrieved from http://www.adaa.org/understanding-anxiety/social-anxiety-disorder

- Soravia, LM; Heinrichs, M; Aerni, A; Maroni, C; Schelling, G; Ehlert, U; Roozendaal, B; de Quervain, DJ (2006). "Glucocorticoids reduce phobic fear in humans". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 103 (14): 5585–90. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103.5585S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0509184103. PMC 1414637. PMID 16567641.

- De Quervain, DJ; Bentz, D; Michael, T; Bolt, OC; Wiederhold, BK; Margraf, J; Wilhelm, FH (2011). "Glucocorticoids enhance extinction-based psychotherapy". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 108 (16): 6621–5. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.6621D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1018214108. PMC 3081033. PMID 21444799.

- Mellings, T. M. B.; Alden, L. E. (2000). "Cognitive processes in social anxiety: the effects of self- focus, rumination and anticipatory processing". Behaviour Research and Therapy. 38 (3): 243–257. doi:10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00040-6. PMID 10665158.

- Stravynski, A.; Bond, S.; Amado, D. (2004). "Cognitive causes of social phobia: a critical appraisal". Clinical Psychology Review. 24 (4): 421–440. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2004.01.006. PMID 15245829.

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2011). Obsessive-compulsive disorder, ocd. Retrieved from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/obsessive-compulsive-disorder-ocd/index.shtml

- Mayo Clinic Staff. (2010). Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Retrieved from http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/obsessive-compulsive-disorder/DS00189

- D.J. Stein. "Obsessive-compulsive disorder". The Lancet (August 2002), 360 (9330), pg. 397-405

- Eddy, M, F., & Walbroehl, G, S. (1998). Recognition and treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Retrieved from http://www.aafp.org/afp/980401ap/eddy.html

- Wilhelm, S.; McNally, R.J.; Baer, L.; Florin, I. (1996). "Directed forgetting in obsessive-compulsive disorder". Behaviour Research and Therapy. 34 (8): 633–641. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(96)00040-x. PMID 8870289.

- Tolin, D. F.; Abramowitz, J. S.; Brigidi, B. D.; Amir, N.; Street, G. P. (2001). "Memory and memory confidence in obsessive–compulsive disorder". Behaviour Research and Therapy. 39 (8): 913–927. doi:10.1016/s0005-7967(00)00064-4. PMID 11480832.

- Arnsten, AF (2010). "Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function". Nat Rev Neurosci. 10 (6): 410–22. doi:10.1038/nrn2648. PMC 2907136. PMID 19455173.

- Qin, S; Hermans, EJ; van Marle, H; Luo, J; Fernández, G (2009). "Acute Psychological Stress Reduces Working Memory-Related Activity in the Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex". Biological Psychiatry. 66 (1): 25–32. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.03.006. PMID 19403118. S2CID 22601360.

- Porcelli, AJ; et al. (2008). "The effects of acute stress on human prefrontal working memory systems". Physiology & Behavior. 95 (3): 282–289. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2008.04.027. PMID 18692209. S2CID 8816105.

- Qin, S; Cousijn, H; Rijpkema, M; Luo, J; Franke, B; Hermans, EJ; Fernández, G (2012). "The effect of moderate acute psychological stress on working memory-related neural activity is modulated by a genetic variation in catecholaminergic function in humans". Front Integr Neurosci. 6: 16. doi:10.3389/fnint.2012.00016. PMC 3350069. PMID 22593737.