Empty nose syndrome

Empty nose syndrome (ENS) is a potential complication of nasal surgery. ENS is a clinical syndrome that is often referred to as one form of secondary atrophic rhinitis in the medical literature.[1][2] People with ENS have usually undergone a turbinectomy (removal or reduction of turbinates, structures inside the nose) or other surgical procedures that interfere with turbinates; the overall incidence is unknown but it appears to occur in a small percentage of people who undergo nasal surgery. People with ENS may experience a range of symptoms, most commonly feelings of nasal obstruction, nasal dryness and crusting, and a sensation of being unable to breathe.[3]

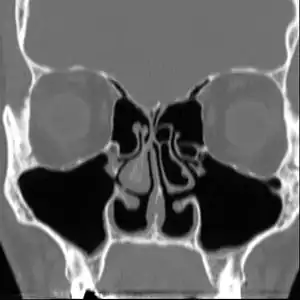

| Empty Nose Syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

| Altered nasal anatomy after bilateral subtotal inferior turbinectomy. | |

| Specialty | Otolaryngology |

The condition is caused by medical interventions and can be caused by any surgical procedure that alters the airflow in the nasal passages, both minor "conservative" surgical procedures as well as by major nasal surgical procedures. It is often seen with people who have unobstructed nasal passages following surgical intervention. Previously surgeons believed ENS was limited to those with complete turbinate resection but through ENS awareness it has been found in patients with a large range of nasal surgeries and occurs any time the body does not adapt to the new airflow.[3][4][5][6][7]

- Major procedures: turbinate surgery (turbinectomy, turbinoplasty) for removal or reduction or modification of turbinates

- Minor procedures: submucosal cautery, submucosal resection, laser therapy, turbinate outfracture, septoplasty, hump reduction and cryosurgery.

The existence as a medical condition was previously controversial and has recently been more accepted in the ear, nose and throat (ENT) specialists and plastic surgeon community but corrective surgical methods are experimental and limited to a few ENTs worldwide. This is due to many ENTs and plastic surgeons not fully understanding the airflow changes that occur when they modify the nose, a lack of understanding in why some patients exhibit the symptoms while others do not and incorrectly assuming that patients exhibiting ENS symptoms are due to mental illness.[3] Despite all aspects of it having been subject to debate, including whether it should be considered solely rhinologic or whether it may have neurological or psychosomatic aspects, it has recently been gaining more acceptance in the ENT community.[3][4][8][9][10][11]

Signs and symptoms

There are no objective physical examination findings that definitely diagnose ENS.[3] Patients begin to notice any of the following symptoms following surgery to their nose or nasal passages: lightheaded/dizziness, brain fog, tingling in hands/mouth, chest pain, muscle spasms, acid reflux, feelings of nasal obstruction, nasal dryness and crusting, dryness in throat and a sensation of being unable to breathe, a feeling of nasal obstruction and crusting, oozing, and foul smells inside the nose from infections.[3] A person with ENS may complain of pain in their nose or face, an inability to sleep, fatigue, and feeling irritated, depressed, or anxious; they may be constantly distracted by the sense that they are not getting enough air.[3]

A study, found that 77% of patients with empty nose syndrome have hyperventilation syndrome.[12] Hyperventilation symptoms can be explained in ENS patients due the change in nasal airflow. This is typically only relieved by correcting the airflow in the nose which is incredibly difficult and should be done carefully to avoid a failed revision surgery.

Cause

The cause of ENS is due to the body not accepting the new airflow in the nasal passages following surgical procedures. The nose is an incredibly complex area of the body and one that has been very poorly researched in terms of the effects on aerodynamics from surgical procedures. In many patients with ENS, the airflow is modeled as being more turbulent with less laminar flow across the mucosa. This change in airflow leads to an imbalance of CO2/O2 levels in the body, which will show hyperventilation-like symptoms in patients. This reduced amount of mucus in the nose can also be attributed to the change in airflow often resulting in dry cool air hitting the back of the patients throat.

One possible cause may be changes to the nasal mucous membrane and to the nerve endings in the mucosa resulting from chronic changes to the temperature and humidity of the air flowing inside the nose, caused in turn by removal or reduction of the turbinates.[3][4] Direct damage to the nerves may be a result of surgical intervention; however, as of 2015, there is no technology that allows the mapping of the sensory nerves within the nose, so it is difficult to determine whether this is causative of ENS.[3] Investigators have been unable to identify consistent diagnostic or precipitating features, psychological causes leading to a psychosomatic condition have been proposed.[3][8][9][11]

Diagnosis

No consensus criteria exist for the diagnosis of ENS and many ENTs will wait a year before diagnosing in hopes the patient accepts the new airflow; it is typically diagnosed by ruling out other conditions, with ENS remaining the likely diagnosis if the signs and symptoms are present.[3][4][8] A "cotton test" has been proposed, in which moist cotton is held where a turbinate should be or in various locations in the nasal passages, to see if it provides relief and an airflow pattern that allows for natural breathing; while this has not been validated nor is it widely accepted, it may be useful to identify which people may benefit from surgery.[3][4][8]

As of 2015, protocols for using rhinomanometry to diagnose ENS and measure response to surgery were under development,[4][8] as was a standardized clinical instrument (a well defined and validated questionnaire) to obtain more useful reporting of symptoms.[8]

A validated ENS-specific, 6-item questionnaire called the Empty Nose Syndrome 6-item Questionnaire (ENS6Q) was developed as an adjunct to the standard Sino-Nasal Outcome Test 22 (SNOT-22).[13] The ENS6Q is the first validated, specific, adjunct questionnaire to the SNOT-22. It can more reliably identify patients suspected of ENS.[14] The ENS6Q is gaining usage in studies on ENS.

Classification

Four types have been proposed:[3]

- ENS secondary to inferior turbinate resection

- ENS secondary to middle turbinate resection

- ENS secondary to both inferior and middle turbinate

- ENS after turbinate-sparing procedures

Prevention

Attempt non surgical methods for an extended period of time prior to surgical intervention. Avoid any unnecessary nasal surgery, avoid any surgical treatment to the turbinates and septum, seek multiple consults for any nasal surgery, conduct imagery on the nasal passages prior to any surgical treatment, seek opinions from surgeons familiar with ENS.[3][15] Many surgeons will tell patients that ENS is only seen in patients that have excessive turbinate reduction, but studies have shown that any change in the airflow of the nose can potentially lead to ENS. For this reason it is critical that anyone planning any surgery to the nose for function or appearance should be aware of the high risk of ENS developing if the body does not accept the new airflow and exchange of gasses.

Treatment

Treatment of ENS by many ENTs is extremely limited with very marginal success rates once diagnosed. Initial treatment is similar to atrophic rhinitis, namely keeping the nasal mucosa moist with saline or oil-based lubricants and treating pain and infection as they arise; adding menthol to lubricants may be helpful in ENS, as may be use of a cool mist humidifier at home but has limited success and many ENT patients seek treatment from the few ENTs well educated in ENS surgical techniques.[3] For people with anxiety, depression, or who are obsessed with the feeling that they can't breathe, psychiatric or psychological care may be helpful.[3][8]

In some people, surgery to restore missing or reduced turbinates or various fillers that correct the airflow in the nose may be beneficial.[3]

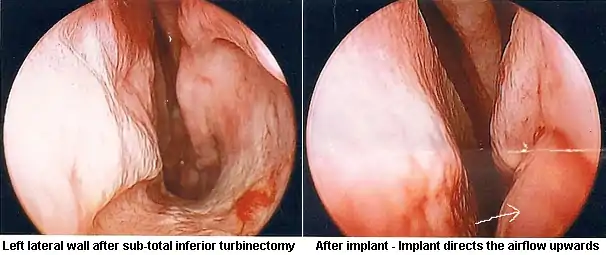

A 2015 meta-analysis identified 128 people treated with surgery from eight studies that were useful to pool, with an age range of 18 to 64, most of whom had been experiencing ENS symptoms for many years. The most common surgical approach was creating a pocket under the mucosa and implanting material - the amount and location were based on the judgement of the surgeon. In about half the cases a filler such as noncellular dermis, a medical-grade porous high-density polyethylene, or silastic was used and in about 40% cartilage taken from the person or from a cow was used. In a few cases hyaluronic acid was injected and in a few others tricalcium phosphate was used. There were no complications caused by the surgery, although one person was over-corrected and developed chronic rhinosinusitis and two people were under-corrected. The hyaluronic acid was completely resorbed in the three people who received it at the one year follow up, and in six people some of the implant came out, but this did not affect the result as enough remained. About 21% of the people had no or marginal improvement but the rest reported significant relief of their symptoms. Since none of the studies used placebo or blinding there may be a strong placebo effect or bias in reporting.[8]

Outcomes

Empty nose syndrome has been observed to affect a small proportion of people who have undergone surgery to the nose or sinuses, particularly those who have undergone turbinectomy (a procedure that removes some of the bones in the nasal passage). The incidence of ENS is variable and has not yet been quantified due to many ENTs failing to accept the condition until recently and could potentially be much more prevalent than once believed.[3][4][8][9][15]

Untreated, the condition can cause significant and longterm physical and emotional distress in some people; some of the initial presentations on the condition described people who committed suicide.[8] It is difficult to determine what treatments are safe and effective, and to what extent, in part because the diagnosis itself is unclear.[8]

History

As early as 1914, Dr Albert Mason reported cases of "a condition resembling atrophic rhinitis" with "a dryness of the nose and throat" following turbinectomy. Mason called the turbinates "the most important organ in the nose" and claimed they were "slaughtered and removed with discriminate abandon more than any other part of the body, with the possible exception of the prepuce."[16]

The term "Empty Nose Syndrome" was first used by Eugene Kern and Monika Stenkvist of the Mayo Clinic in 1994.[3] Kern and Eric Moore published a case study of 242 people with secondary atrophic rhinitis in 2001 and were the first to attribute the cause to prior sinonasal surgery in the scientific literature.[3][1] Whether the condition existed or not and whether surgery was a cause, was hotly debated at Nose 2000, a meeting of the International Rhinologic Society that occurs every four years, and continued to be debated thereafter at scientific meetings and in the literature;[3][17] as an example of how heated the debate became, in a 2002 textbook on nasal reconstruction techniques, two surgeons from University of Utrecht called turbinectomies a "nasal crime".[3]

Society and culture

As of 2016, according to Spencer Payne, a doctor who studies ENS, many people with ENS symptoms commonly encounter doctors who consider their symptoms to be purely psychological;[18] according to Subinoy Das, another doctor who studies ENS, recognition among rhinologists was growing.[19]

People who experience ENS have formed online communities to support one another[3] and to advocate for recognition, prevention, and treatments for ENS.[19]

References

- Moore EJ, Kern EB (2001). "Atrophic rhinitis: a review of 242 cases". Am J Rhinol. 15 (6): 355–61. doi:10.1177/194589240101500601. PMID 11777241. S2CID 13747312.

- deShazo, Richard D; Stringer, Scott P (February 2011). "Atrophic rhinosinusitis: progress toward explanation of an unsolved medical mystery". Current Opinion in Allergy & Clinical Immunology. 11 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1097/ACI.0b013e328342333e. ISSN 1528-4050. PMID 21157302. S2CID 27205163.

- Kuan, EC; Suh, JD; Wang, MB (2015). "Empty nose syndrome". Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 15 (1): 493. doi:10.1007/s11882-014-0493-x. PMID 25430954. S2CID 43309184.

- Sozansky J, Houser SM (Jan 2015). "Pathophysiology of empty nose syndrome". Laryngoscope. 125 (1): 70–4. doi:10.1002/lary.24813. PMID 24978195. S2CID 29735233.

- Houser, Steven M. (2007-09-01). "Surgical Treatment for Empty Nose Syndrome". Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. 133 (9): 858–863. doi:10.1001/archotol.133.9.858. ISSN 0886-4470. PMID 17875850.

Although total turbinate excision is most frequently the cause of ENS, lesser procedures (eg, submucosal cautery, submucosal resection, cryosurgery, turbinate outfracture) to reduce the turbinates and nasal grafts (spreader grafts, butterfly grafts) and septoplasties often cause ENS related symptoms as well.

- "FFAAIR | Syndrome du Nez Vide (SNV)". www.ffaair.org (in French). Retrieved 2019-09-11.

suite d'interventions endonasales diverses (turbinectomie, turbinoplastie, cautérisation)

- Saafan. "Empty nose syndrome: etiopathogenesis and management". www.ejo.eg.net. Retrieved 2019-09-11.

ENS is a complication of middle and/or inferior turbinate surgery, most frequently total turbinate excision, but also with minor procedures such as submucosal cautery, submucosal resection, laser therapy, and cryosurgery if performed in an aggressive manner

- Leong SC (Jul 2015). "The clinical efficacy of surgical interventions for empty nose syndrome: A systematic review". Laryngoscope. 125 (7): 1557–62. doi:10.1002/lary.25170. PMID 25647010. S2CID 206202553.

- Coste, A; Dessi, P; Serrano, E (2012). "Empty nose syndrome". Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 129 (2): 93–7. doi:10.1016/j.anorl.2012.02.001. PMID 22513047.

- Hildenbrand, T; Weber, RK; Brehmer, D (2011). "Rhinitis sicca, dry nose and atrophic rhinitis: a review of the literature". Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 268 (1): 17–26. doi:10.1007/s00405-010-1391-z. PMID 20878413. S2CID 34729974.

- Payne SC (2009). "Empty nose syndrome: what are we really talking about?". Otolaryngol. Clin. North Am. 42 (2): 331–7, ix–x. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2009.02.002. PMID 19328896.

- Mangin, David; Bequignon, Emilie; Zerah-Lancner, Francoise; Isabey, Daniel; Louis, Bruno; Adnot, Serge; Papon, Jean-François; Coste, André; Boyer, Laurent (September 2017). "Investigating hyperventilation syndrome in patients suffering from empty nose syndrome". The Laryngoscope. 127 (9): 1983–1988. doi:10.1002/lary.26599. ISSN 1531-4995. PMID 28407251. S2CID 25389674.

- Soler, ZM; Jones, R; Le, P; Rudmik, L; Mattos, JL; Nguyen, SA; Schlosser, RJ (March 2018). "Sino-Nasal outcome test-22 outcomes after sinus surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis". The Laryngoscope. 128 (3): 581–592. doi:10.1002/lary.27008. PMC 5814358. PMID 29164622.

- Velasquez, N; Thamboo, A; Habib, A-RR; Huang, Z; Nayak, JV (2017). "The Empty Nose Syndrome 6‐item Questionnaire: a validated 6‐item questionnaire as a diagnostic aid for empty nose syndrome patients". Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 7 (1): 64–71. doi:10.1002/alr.21842. PMID 27557473. S2CID 40730623.

- Gehani NC and Houser S. Septoplasty, Turbinate Reduction, and Correction of Nasal Obstruction. Chapter 42. in Bailey's Head and Neck Surgery: Otolaryngology. Ed Jonas Johnson: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Jul 9, 2013 ISBN 9781609136024

- Mason, Albert (September 1914). "A plea for the conservation of the inferior turbinate". Atlanta Journal-record of Medicine. 61 (6): 245–249. PMC 9038343. PMID 36020266.

- Aaron Zitner for The Los Angeles Times. May 10, 2001 Sniffing at Empty Nose Idea

- Tomas Harmon for CBS19 May 4, 2016 Medical Mystery: Empty Nose Syndrome

- Joel Oliphint for BuzzFeed. April 14, 2016 Is Empty Nose Syndrome Real? And If Not, Why Are People Killing Themselves Over It

External links

- American Rhinologic Society: Empty nose syndrome

- United Kingdom National Health Service: Atrophic Rhinitis Causes