Facial nerve paralysis

Facial nerve paralysis is a common problem that involves the paralysis of any structures innervated by the facial nerve. The pathway of the facial nerve is long and relatively convoluted, so there are a number of causes that may result in facial nerve paralysis.[2] The most common is Bell's palsy,[3][4] a disease of unknown cause that may only be diagnosed by exclusion of identifiable serious causes.

| Facial nerve paralysis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Facial palsy, prosopoplegia[1] |

| |

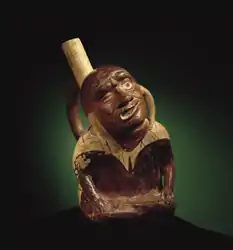

| Moche culture representation of facial paralysis. 300 AD, Larco Museum Collection, Lima, Peru | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

Signs and symptoms

Facial nerve paralysis is characterised by facial weakness, usually only in one side of the face, with other symptoms possibly including loss of taste, hyperacusis and decreased salivation and tear secretion. Other signs may be linked to the cause of the paralysis, such as vesicles in the ear, which may occur if the facial palsy is due to shingles. Symptoms may develop over several hours.[5] : 1228 Acute facial pain radiating from the ear may precede the onset of other symptoms.[6] : 2585

Causes

Bell's palsy

Bell's palsy is the most common cause of acute facial nerve paralysis.[3][4] There is no known cause of Bell's palsy,[5][6] although it has been associated with herpes simplex infection. Bell's palsy may develop over several days, and may last several months, in the majority of cases recovering spontaneously. It is typically diagnosed clinically, in patients with no risk factors for other causes, without vesicles in the ear, and with no other neurological signs. Recovery may be delayed in the elderly, or those with a complete paralysis. Bell's palsy is often treated with corticosteroids.[5][6]

Infection

Lyme disease, an infection caused by Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria and spread by ticks, can account for about 25% of cases of facial palsy in areas where Lyme disease is common.[7] In the U.S., Lyme is most common in the New England and Mid-Atlantic states and parts of Wisconsin and Minnesota, but it is expanding into other areas.[8] The first sign of about 80% of Lyme infections, typically one or two weeks after a tick bite, is usually an expanding rash that may be accompanied by headaches, body aches, fatigue, or fever.[9] In up to 10-15% of Lyme infections, facial palsy appears several weeks later, and may be the first sign of infection that is noticed, as the Lyme rash typically does not itch and is not painful. Lyme disease is treated with antibiotics.[10][11]

Reactivation of herpes zoster virus, as well as being associated with Bell's palsy, may also be a direct cause of facial nerve palsy. Reactivation of latent virus within the geniculate ganglion is associated with vesicles affecting the ear canal, and termed Ramsay Hunt syndrome type II.[6] In addition to facial paralysis, symptoms may include ear pain and vesicles, sensorineural hearing loss, and vertigo. Management includes antiviral drugs and oral steroids.

Otitis media is an infection in the middle ear, which can spread to the facial nerve and inflame it, causing compression of the nerve in its canal. Antibiotics are used to control the otitis media, and other options include a wide myringotomy (an incision in the tympanic membrane) or decompression if the patient does not improve. Chronic otitis media usually presents in an ear with chronic discharge (otorrhea), or hearing loss, with or without ear pain (otalgia). Once suspected, there should be immediate surgical exploration to determine if a cholesteatoma has formed as this must be removed if present. Inflammation from the middle ear can spread to the canalis facialis of the temporal bone - through this canal travels the facial nerve together with the statoacoustisus nerve. In the case of inflammation the nerve is exposed to edema and subsequent high pressure, resulting in a periferic type palsy.

Trauma

In blunt trauma, the facial nerve is the most commonly injured cranial nerve.[12] Physical trauma, especially fractures of the temporal bone, may also cause acute facial nerve paralysis. Understandably, the likelihood of facial paralysis after trauma depends on the location of the trauma. Most commonly, facial paralysis follows temporal bone fractures, though the likelihood depends on the type of fracture.

Transverse fractures in the horizontal plane present the highest likelihood of facial paralysis (40-50%). Patients may also present with blood behind the tympanic membrane, sensory deafness, and vertigo; the latter two symptoms due to damage to vestibulocochlear nerve and the inner ear. Longitudinal fracture in the vertical plane present a lower likelihood of paralysis (20%). Patients may present with blood coming out of the external auditory meatus), tympanic membrane tear, fracture of external auditory canal, and conductive hearing loss. In patients with mild injuries, management is the same as with Bell's palsy – protect the eyes and wait. In patients with severe injury, progress is followed with nerve conduction studies. If nerve conduction studies show a large (>90%) change in nerve conduction, the nerve should be decompressed. The facial paralysis can follow immediately the trauma due to direct damage to the facial nerve, in such cases a surgical treatment may be attempted. In other cases the facial paralysis can occur a long time after the trauma due to oedema and inflammation. In those cases steroids can be a good help.

Tumors

A tumor compressing the facial nerve anywhere along its complex pathway can result in facial paralysis. Common culprits are facial neuromas, congenital cholesteatomas, hemangiomas, acoustic neuromas, parotid gland neoplasms, or metastases of other tumours.[13][14]

Often, since facial neoplasms have such an intimate relationship with the facial nerve, removing tumors in this region becomes perplexing as the physician is unsure how to manage the tumor without causing even more palsy. Typically, benign tumors should be removed in a fashion that preserves the facial nerve, while malignant tumors should always be resected along with large areas of tissue around them, including the facial nerve. While this will inevitably lead to facial paralysis, safe removal of a malignant neoplasm is vital for patient survival. After tumor removal, the facial nerve can be reinnervated with techniques such as cross-facial nerve grafting, nerve transfers and end-to-end nerve repair.[15] Alternative treatment methods include muscle transfer techniques, such as the gracilis free muscle transfer[16] or static procedures.

Patients with facial nerve paralysis resulting from tumours usually present with a progressive, twitching paralysis, other neurological signs, or a recurrent Bell's palsy-type presentation. The latter should always be suspicious, as Bell's palsy should not recur. A chronically discharging ear must be treated as a cholesteatoma until proven otherwise; hence, there must be immediate surgical exploration. Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance (MR) imaging should be used to identify the location of the tumour, and it should be managed accordingly.

Other neoplastic causes include leptomeningeal carcinomatosis.

Stroke

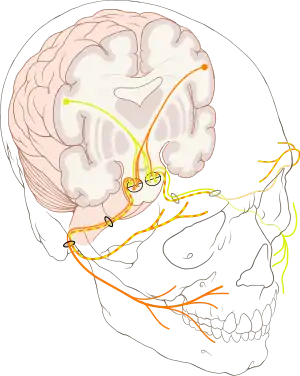

Central facial palsy can be caused by a lacunar infarct affecting fibers in the internal capsule going to the nucleus. The facial nucleus itself can be affected by infarcts of the pontine arteries. Unlike peripheral facial palsy, central facial palsy does not affect the forehead, because the forehead is served by nerves coming from both motor cortexes.[7]

Other

Other causes may include:

- Diabetes mellitus[6]

- Facial nerve paralysis, sometimes bilateral, is a common manifestation of sarcoidosis of the nervous system, neurosarcoidosis.[6]

- Bilateral facial nerve paralysis may occur in Guillain–Barré syndrome, an autoimmune condition of the peripheral nervous system.[6]

- Moebius syndrome is a bilateral facial paralysis resulting from the underdevelopment of the VII cranial nerve (facial nerve), which is present at birth. The VI cranial nerve, which controls lateral eye movement, is also affected, so people with Moebius syndrome cannot form facial expression or move their eyes from side to side. Moebius syndrome is extremely rare, and its cause or causes are not known.

- Facial piercings, namely eyebrow piercings or tongue piercings, can in very rare cases cause damage to the facial nerve.

Diagnosis

A medical history and physical examination, including a neurological examination, are needed for diagnosis. The first step is to observe what parts of the face do not move normally when the person tries to smile, blink, or raise the eyebrows. If the forehead wrinkles normally, a diagnosis of central facial palsy is made, and the person should be evaluated for stroke.[7] Otherwise, the diagnosis is peripheral facial palsy, and its cause needs to be identified, if possible. Ramsey Hunt's syndrome causes pain and small blisters in the ear on the same side as the palsy. Otitis media, trauma, or post-surgical complications may alternatively become apparent from history and physical examination. If there is a history of trauma, or a tumour is suspected, a CT scan or MRI may be used to clarify its impact. Blood tests or x-rays may be ordered depending on suspected causes.[6] The likelihood that the facial palsy is caused by Lyme disease should be estimated, based on recent history of outdoor activities in likely tick habitats during warmer months, recent history of rash or symptoms such as headache and fever, and whether the palsy affects both sides of the face (much more common in Lyme than in Bell's palsy). If that likelihood is more than negligible, a serological test for Lyme disease should be performed. If the test is positive, the diagnosis is Lyme disease. If no cause is found, the diagnosis is Bell's Palsy.

Classification

Facial nerve paralysis may be divided into supranuclear and infranuclear lesions. In a clinical setting, other commonly used classifications include: intra-cranial and extra-cranial; acute, subacute and chronic duration.[17]

Supranuclear and nuclear lesions

Central facial palsy can be caused by a lacunar infarct affecting fibers in the internal capsule going to the nucleus. The facial nucleus itself can be affected by infarcts of the pontine arteries. These are corticobulbar fibers travelling in internal capsule.

Infranuclear lesions

Infranuclear lesions refer to the majority of causes of facial palsy.

Treatment

If an underlying cause has been found for the facial palsy, it should be treated. If it is estimated that the likelihood that the facial palsy is caused by Lyme disease exceeds 10%, empiric therapy with antibiotics should be initiated, without corticosteroids, and reevaluated upon completion of laboratory tests for Lyme disease.[7] All other patients should be treated with corticosteroids and, if the palsy is severe, antivirals. Facial palsy is considered severe if the person is unable to close the affected eye completely or the face is asymmetric even at rest. Corticosteroids initiated within three days of Bell's palsy onset have been found to increase chances of recovery, reduce time to recovery, and reduce residual symptoms in case of incomplete recovery.[7] However, for facial palsy caused by Lyme disease, corticosteroids have been found in some studies to harm outcomes.[7] Other studies have found antivirals to possibly improve outcomes relative to corticosteroids alone for severe Bell's palsy.[7] In those whose blinking is disrupted by the facial palsy, frequent use of artificial tears while awake is recommended, along with ointment and a patch or taping the eye closed when sleeping.[7][18] Several surgical treatment options exist to restore symmetry to the paralyzed face in patients where function does not return (see section Tumors above).

References

- "prosopoplegia". The Free Dictionary. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

- "Facial Nerve". Retrieved 22 November 2009.

- Fuller, G; Morgan, C (31 March 2016). "Bell's palsy syndrome: mimics and chameleons". Practical Neurology. 16 (6): 439–44. doi:10.1136/practneurol-2016-001383. PMID 27034243. S2CID 4480197.

- Dickson, Gretchen (2014). Primary Care ENT, An Issue of Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 138. ISBN 978-0323287173. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016.

- Colledge, Nicki R.; Walker, Brian R.; Ralston, Stuart H., eds. (2010). Davidson's principles and practice of medicine. illust. Robert Britton (21st ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7020-3084-0.

- Fauci, Anthony S.; Harrison, T. R., eds. (2008). Harrison's principles of internal medicine (17th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0-07-147693-5.

- Garro A, Nigrovic LE (May 2018). "Managing Peripheral Facial Palsy". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 71 (5): 618–623. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.08.039. PMID 29110887.

- "Lyme Disease Data and surveillance". Lyme Disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- "Lyme disease rashes and look-alikes". Lyme Disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- Wright WF, Riedel DJ, Talwani R, Gilliam BL (June 2012). "Diagnosis and management of Lyme disease". American Family Physician. 85 (11): 1086–93. PMID 22962880. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013.

- Shapiro ED (May 2014). "Clinical practice. Lyme disease" (PDF). The New England Journal of Medicine. 370 (18): 1724–1731. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1314325. PMC 4487875. PMID 24785207. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2016.

- Cools MJ, Carneiro KA (April 2018). "Facial nerve palsy following mild mastoid trauma on trampoline". Am J Emerg Med. 36 (8): 1522.e1–1522.e3. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2018.04.034. PMID 29861376. S2CID 44106089.

- Thompson AL, Bharatha A, Aviv RI, Nedzelski J, Chen J, Bilbao JM, Wong J, Saad R, Symons SP (July 2009). "Chondromyoid fibroma of the mastoid facial nerve canal mimicking a facial nerve schwannoma". Laryngoscope. 119 (7): 1380–1383. doi:10.1002/lary.20486. PMID 19507235. S2CID 34800452.

- Thompson AL, Aviv RI, Chen JM, Nedzelski JM, Yuen HW, Fox AJ, Bharatha A, Bartlett ES, Symons SP (December 2009). "MR imaging of facial nerve schwannoma". Laryngoscope. 119 (12): 2428–2436. doi:10.1002/lary.20644. PMID 19780031. S2CID 24237419.

- Rodríguez-Lorenzo, Andrés; Tzou, Chieh-Han, eds. (2021). Facial palsy : techniques for reanimation of the paralyzed face. Cham, Switzerland. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-50784-8. ISBN 978-3-030-50784-8. S2CID 235205923. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- Bui, Mai-Anh; Goh, Raymond; Vu, Trung-Truc (11 July 2019). "Dynamic Reanimation of Smile in Facial Paralysis with Gracilis Functioning Free Muscle Flap Innervated by Masseteric Nerve: The First Vietnamese Series". International Microsurgery Journal (Imj). 3 (2). doi:10.24983/scitemed.imj.2019.00116. S2CID 199045428.

- The Plastics Fella Guide to Facial Nerve Anatomy

- Michelle Stephenson (4 October 2012). "OTC Drops: Telling the Tears Apart". Review of Ophtalmology. Jobson Medical Information LLC. Retrieved 16 April 2019.