Fear-avoidance model

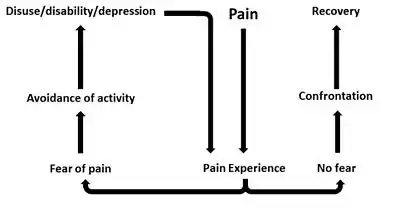

The fear-avoidance model (or FA model) is a psychiatric model that describes how individuals develop and maintain chronic musculoskeletal pain as a result of attentional processes and avoidant behavior based on pain-related fear.[1][2][3] Introduced by Lethem et al. in 1983, this model helped explain how these individuals experience pain despite the absence of pathology.[3][4][5] If an individual experiences acute discomfort and delays the situation by using avoidant behavior, a lack of pain increase reinforces this behavior.[6][7] Increased vulnerability provides positive feedback to the perceived level of pain and rewards avoidant behavior for removing unwanted stimuli.[2][8] If the individual perceives the pain as nonthreatening or temporary, he or she feels less anxious and confronts the pain-related situation.[9]

Avoidant behavior is healthy when encouraging the individual to avoid stressing injuries and permitting them to heal.[7] However, it is harmful when discouraging the individual from activity after the injury is healed.[7] The resulting hypervigilance and disability restricts normal use of the tissue and deteriorates the individual physically and mentally.[8] Once the avoidant behavior is no longer reinforced, the individual exits the positive feedback loop.[2] In 1993, Waddell et al. developed a Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) which showed that fear-avoidance beliefs about physical activities are strongly related to work loss.[3][6]

Examples

Anxiety sensitivity

Anxiety sensitivity is the fear of the symptoms of anxiety. An example of the fear-avoidance model, anxiety sensitivity stems from the fear that the symptoms of anxiety will lead to harmful social and physical effects. As a result, the individual delays the situation by avoiding any stimuli related to pain-inducing situations and activities, becoming restricted in normal daily function.[2]

Chronic pain

Chronic pain is another example that can originate from the drastic misinterpretation of pain as a catastrophe. As a result of this misinterpretation, the individual repeatedly avoids the pain-inducing activity and will likely overestimate any future pain from such activity. The excessive sensitivity to pain discourages the individual from exercise and weakens his or her body.[8]

Criticisms

Research involving the fear-avoidance model has led some to question its accuracy in representing or predicting the actual avoidance of physical activity due to negative reinforcement. In certain cases, the individual completely avoids anxiety-inducing behavior, so that the fear response never becomes directly involved. Other factors affecting the perceived level of danger and spatial awareness further complicate the model. While the fear-avoidance model may be simplistic for every situation involving fear, discomfort, and/or chronic pain, its effectiveness is generally acknowledged for diagnosing and understanding how humans positively or negatively react to fear and anxiety.[8]

References

- Leeuw, M.; Goossens, M. L. E. J. B.; Linton, S. J.; Crombez, G.; Boersma, K.; Vlaeyen, J. W. S. (2006). "The Fear-Avoidance Model of Musculoskeletal Pain: Current State of Scientific Evidence". Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 30 (1): 77–94. doi:10.1007/s10865-006-9085-0. PMID 17180640. S2CID 207186847.

- Pincus, Tamar; Smeets, Rob J.E.M.; Simmonds, Maureen J.; Sullivan, Michael J.L. (November 2010). "The Fear Avoidance Model Disentangled: Improving the Clinical Utility of the Fear Avoidance Model". The Clinical Journal of Pain. 26 (9): 739–746. doi:10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181f15d45. PMID 20842017. S2CID 18667121.

- Vlaeyen, J. W.; Linton, S. J. (2000). "Fear-avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: A state of the art". Pain. 85 (3): 317–332. doi:10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00242-0. PMID 10781906. S2CID 14486753.

- Lethem, J.; Slade, P. D.; Troup, J. D.; Bentley, G. (1983). "Outline of a Fear-Avoidance Model of exaggerated pain perception--I". Behaviour Research and Therapy. 21 (4): 401–408. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(83)90009-8. PMID 6626110.

- From Acute to Chronic Back Pain. Oxford University Press. 2012-01-19. p. 282. ISBN 978-0-19-162572-5. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- Herbert H. Zaretsky; Edwin F. Richter; Myron G. Eisenberg (21 June 2005). Medical Aspects Of Disability: A Handbook For The Rehabilitation Professional. Springer Publishing Company. pp. 223–4. ISBN 978-0-8261-7973-9. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- Asmundson, Gordon; Norton, Peter (1999). "Beyond pain: the role of fear and avoidance in chronicity". Clinical Psychology Review. 19 (1): 97–119. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(98)00034-8. PMID 9987586.

- Crombez, Geert; Eccleston, Christopher; Van Damme, Stefaan; Vlaeyen, Johan W. S.; Karoly, Paul (Jul 2012). "Fear-avoidance model of chronic pain: the next generation". The Clinical Journal of Pain. 28 (6): 475–483. doi:10.1097/AJP.0b013e3182385392. hdl:1854/LU-2960547. ISSN 1536-5409. PMID 22673479. S2CID 8169305.

- Selby, Edward. "Avoidance of Anxiety as Self-Sabotage: How Running Away Can Bite You in the Behind". Psychology Today. Retrieved March 20, 2015.