Cochlea

The cochlea is the part of the inner ear involved in hearing. It is a spiral-shaped cavity in the bony labyrinth, in humans making 2.75 turns around its axis, the modiolus.[2][3] A core component of the cochlea is the Organ of Corti, the sensory organ of hearing, which is distributed along the partition separating the fluid chambers in the coiled tapered tube of the cochlea.

| Cochlea | |

|---|---|

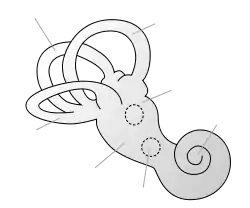

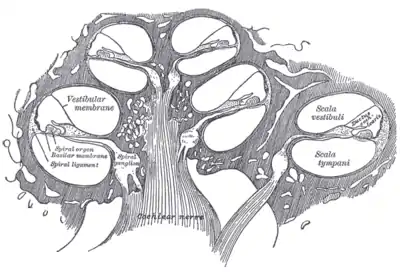

Cross section of the cochlea | |

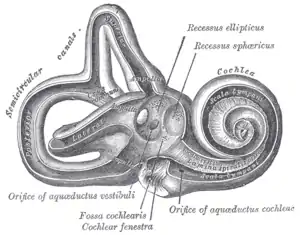

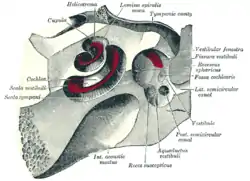

Parts of the inner ear, showing the cochlea | |

| Details | |

| Pronunciation | /ˈkɒkliə, ˈkoʊkliə/[1] |

| Part of | Inner ear |

| System | Auditory system |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Cochlea |

| MeSH | D003051 |

| NeuroLex ID | birnlex_1190 |

| TA98 | A15.3.03.025 |

| TA2 | 6964 |

| FMA | 60201 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

|

| This article is one of a series documenting the anatomy of the |

| Human ear |

|---|

The name cochlea derives from Ancient Greek κοχλίας (kokhlias) 'spiral, snail shell'.

Structure

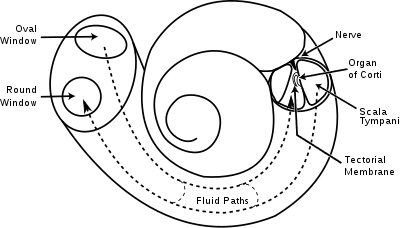

The cochlea (plural is cochleae) is a spiraled, hollow, conical chamber of bone, in which waves propagate from the base (near the middle ear and the oval window) to the apex (the top or center of the spiral). The spiral canal of the cochlea is a section of the bony labyrinth of the inner ear that is approximately 30 mm long and makes 23⁄4 turns about the modiolus. The cochlear structures include:

- Three scalae or chambers:

- the vestibular duct or scala vestibuli (containing perilymph), which lies superior to the cochlear duct and abuts the oval window

- the tympanic duct or scala tympani (containing perilymph), which lies inferior to the cochlear duct and terminates at the round window

- the cochlear duct or scala media (containing endolymph) a region of high potassium ion concentration that the stereocilia of the hair cells project into

- The helicotrema, the location where the tympanic duct and the vestibular duct merge, at the apex of the cochlea

- Reissner's membrane, which separates the vestibular duct from the cochlear duct

- The osseous spiral lamina, a main structural element that separates the cochlear duct from the tympanic duct

- The basilar membrane, a main structural element that separates the cochlear duct from the tympanic duct and determines the mechanical wave propagation properties of the cochlear partition

- The Organ of Corti, the sensory epithelium, a cellular layer on the basilar membrane, in which sensory hair cells are powered by the potential difference between the perilymph and the endolymph

- hair cells, sensory cells in the Organ of Corti, topped with hair-like structures called stereocilia

- The spiral ligament.

The cochlea is a portion of the inner ear that looks like a snail shell (cochlea is Greek for snail).[4] The cochlea receives sound in the form of vibrations, which cause the stereocilia to move. The stereocilia then convert these vibrations into nerve impulses which are taken up to the brain to be interpreted. Two of the three fluid sections are canals and the third is the 'Organ of Corti' which detects pressure impulses that travel along the auditory nerve to the brain. The two canals are called the vestibular canal and the tympanic canal.

Microanatomy

The walls of the hollow cochlea are made of bone, with a thin, delicate lining of epithelial tissue. This coiled tube is divided through most of its length by an inner membranous partition. Two fluid-filled outer spaces (ducts or scalae) are formed by this dividing membrane. At the top of the snailshell-like coiling tubes, there is a reversal of the direction of the fluid, thus changing the vestibular duct to the tympanic duct. This area is called the helicotrema. This continuation at the helicotrema allows fluid being pushed into the vestibular duct by the oval window to move back out via movement in the tympanic duct and deflection of the round window; since the fluid is nearly incompressible and the bony walls are rigid, it is essential for the conserved fluid volume to exit somewhere.

The lengthwise partition that divides most of the cochlea is itself a fluid-filled tube, the third 'duct'. This central column is called the cochlear duct. Its fluid, endolymph, also contains electrolytes and proteins, but is chemically quite different from perilymph. Whereas the perilymph is rich in sodium ions, the endolymph is rich in potassium ions, which produces an ionic, electrical potential.

The hair cells are arranged in four rows in the Organ of Corti along the entire length of the cochlear coil. Three rows consist of outer hair cells (OHCs) and one row consists of inner hair cells (IHCs). The inner hair cells provide the main neural output of the cochlea. The outer hair cells, instead, mainly 'receive' neural input from the brain, which influences their motility as part of the cochlea's mechanical "pre-amplifier". The input to the OHC is from the olivary body via the medial olivocochlear bundle.

The cochlear duct is almost as complex on its own as the ear itself. The cochlear duct is bounded on three sides by the basilar membrane, the stria vascularis, and Reissner's membrane. The stria vascularis is a rich bed of capillaries and secretory cells; Reissner's membrane is a thin membrane that separates endolymph from perilymph; and the basilar membrane is a mechanically somewhat stiff membrane, supporting the receptor organ for hearing, the Organ of Corti, and determines the mechanical wave propagation properties of the cochlear system.

Function

The cochlea is filled with a watery liquid, the endolymph, which moves in response to the vibrations coming from the middle ear via the oval window. As the fluid moves, the cochlear partition (basilar membrane and organ of Corti) moves; thousands of hair cells sense the motion via their stereocilia, and convert that motion to electrical signals that are communicated via neurotransmitters to many thousands of nerve cells. These primary auditory neurons transform the signals into electrochemical impulses known as action potentials, which travel along the auditory nerve to structures in the brainstem for further processing.

Hearing

The stapes (stirrup) ossicle bone of the middle ear transmits vibrations to the fenestra ovalis (oval window) on the outside of the cochlea, which vibrates the perilymph in the vestibular duct (upper chamber of the cochlea). The ossicles are essential for efficient coupling of sound waves into the cochlea, since the cochlea environment is a fluid–membrane system, and it takes more pressure to move sound through fluid–membrane waves than it does through air. A pressure increase is achieved by reducing the area ratio from the tympanic membrane (drum) to the oval window (stapes bone) by 20. As pressure = force/area, results in a pressure gain of about 20 times from the original sound wave pressure in air. This gain is a form of impedance matching – to match the soundwave travelling through air to that travelling in the fluid–membrane system.

At the base of the cochlea, each 'duct' ends in a membranous portal that faces the middle ear cavity: The vestibular duct ends at the oval window, where the footplate of the stapes sits. The footplate vibrates when the pressure is transmitted via the ossicular chain. The wave in the perilymph moves away from the footplate and towards the helicotrema. Since those fluid waves move the cochlear partition that separates the ducts up and down, the waves have a corresponding symmetric part in perilymph of the tympanic duct, which ends at the round window, bulging out when the oval window bulges in.

The perilymph in the vestibular duct and the endolymph in the cochlear duct act mechanically as a single duct, being kept apart only by the very thin Reissner's membrane. The vibrations of the endolymph in the cochlear duct displace the basilar membrane in a pattern that peaks a distance from the oval window depending upon the soundwave frequency. The Organ of Corti vibrates due to outer hair cells further amplifying these vibrations. Inner hair cells are then displaced by the vibrations in the fluid, and depolarise by an influx of K+ via their tip-link-connected channels, and send their signals via neurotransmitter to the primary auditory neurons of the spiral ganglion.

The hair cells in the Organ of Corti are tuned to certain sound frequencies by way of their location in the cochlea, due to the degree of stiffness in the basilar membrane.[5] This stiffness is due to, among other things, the thickness and width of the basilar membrane,[6] which along the length of the cochlea is stiffest nearest its beginning at the oval window, where the stapes introduces the vibrations coming from the eardrum. Since its stiffness is high there, it allows only high-frequency vibrations to move the basilar membrane, and thus the hair cells. The farther a wave travels towards the cochlea's apex (the helicotrema), the less stiff the basilar membrane is; thus lower frequencies travel down the tube, and the less-stiff membrane is moved most easily by them where the reduced stiffness allows: that is, as the basilar membrane gets less and less stiff, waves slow down and it responds better to lower frequencies. In addition, in mammals, the cochlea is coiled, which has been shown to enhance low-frequency vibrations as they travel through the fluid-filled coil.[7] This spatial arrangement of sound reception is referred to as tonotopy.

For very low frequencies (below 20 Hz), the waves propagate along the complete route of the cochlea – differentially up vestibular duct and tympanic duct all the way to the helicotrema. Frequencies this low still activate the Organ of Corti to some extent but are too low to elicit the perception of a pitch. Higher frequencies do not propagate to the helicotrema, due to the stiffness-mediated tonotopy.

A very strong movement of the basilar membrane due to very loud noise may cause hair cells to die. This is a common cause of partial hearing loss and is the reason why users of firearms or heavy machinery often wear earmuffs or earplugs.

Hair cell amplification

Not only does the cochlea "receive" sound, a healthy cochlea generates and amplifies sound when necessary. Where the organism needs a mechanism to hear very faint sounds, the cochlea amplifies by the reverse transduction of the OHCs, converting electrical signals back to mechanical in a positive-feedback configuration. The OHCs have a protein motor called prestin on their outer membranes; it generates additional movement that couples back to the fluid–membrane wave. This "active amplifier" is essential in the ear's ability to amplify weak sounds.[8][9]

The active amplifier also leads to the phenomenon of soundwave vibrations being emitted from the cochlea back into the ear canal through the middle ear (otoacoustic emissions).

Otoacoustic emissions

Otoacoustic emissions are due to a wave exiting the cochlea via the oval window, and propagating back through the middle ear to the eardrum, and out the ear canal, where it can be picked up by a microphone. Otoacoustic emissions are important in some types of tests for hearing impairment, since they are present when the cochlea is working well, and less so when it is suffering from loss of OHC activity.

Role of gap junctions

Gap-junction proteins, called connexins, expressed in the cochlea play an important role in auditory functioning.[10] Mutations in gap-junction genes have been found to cause syndromic and nonsyndromic deafness.[11] Certain connexins, including connexin 30 and connexin 26, are prevalent in the two distinct gap-junction systems found in the cochlea. The epithelial-cell gap-junction network couples non-sensory epithelial cells, while the connective-tissue gap-junction network couples connective-tissue cells. Gap-junction channels recycle potassium ions back to the endolymph after mechanotransduction in hair cells.[12] Importantly, gap junction channels are found between cochlear supporting cells, but not auditory hair cells.[13]

Clinical significance

Hearing loss

Other animals

The coiled form of cochlea is unique to mammals. In birds and in other non-mammalian vertebrates, the compartment containing the sensory cells for hearing is occasionally also called "cochlea," despite not being coiled up. Instead, it forms a blind-ended tube, also called the cochlear duct. This difference apparently evolved in parallel with the differences in frequency range of hearing between mammals and non-mammalian vertebrates. The superior frequency range in mammals is partly due to their unique mechanism of pre-amplification of sound by active cell-body vibrations of outer hair cells. Frequency resolution is, however, not better in mammals than in most lizards and birds, but the upper frequency limit is – sometimes much – higher. Most bird species do not hear above 4–5 kHz, the currently known maximum being ~ 11 kHz in the barn owl. Some marine mammals hear up to 200 kHz. A long coiled compartment, rather than a short and straight one, provides more space for additional octaves of hearing range, and has made possible some of the highly derived behaviors involving mammalian hearing.[16]

As the study of the cochlea should fundamentally be focused at the level of hair cells, it is important to note the anatomical and physiological differences between the hair cells of various species. In birds, for instance, instead of outer and inner hair cells, there are tall and short hair cells. There are several similarities of note in regard to this comparative data. For one, the tall hair cell is very similar in function to that of the inner hair cell, and the short hair cell, lacking afferent auditory-nerve fiber innervation, resembles the outer hair cell. One unavoidable difference, however, is that while all hair cells are attached to a tectorial membrane in birds, only the outer hair cells are attached to the tectorial membrane in mammals.

History

The name cochlea is derived from the Latin word for snail shell, which in turn is from the Greek κοχλίας kokhlias ("snail, screw"), from κόχλος kokhlos ("spiral shell")[17] in reference to its coiled shape; the cochlea is coiled in mammals with the exception of monotremes.

Additional images

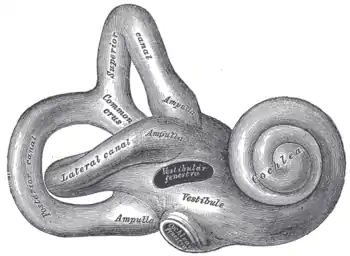

Right osseous labyrinth. Lateral view.

Right osseous labyrinth. Lateral view. Interior of right osseous labyrinth.

Interior of right osseous labyrinth. The cochlea and vestibule, viewed from above.

The cochlea and vestibule, viewed from above. Cross-section of the cochlea.

Cross-section of the cochlea.

See also

- Bony labyrinth

- Membranous labyrinth

- Cochlear implant

- Cochlear nerve

- Cochlear nuclei

- Evolution of the cochlea

- Noise health effects

References

- "cochlea". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- Anne M. Gilroy; Brian R. MacPherson; Lawrence M. Ross (2008). Atlas of anatomy. Thieme. p. 536. ISBN 978-1-60406-151-2.

- Moore & Dalley (1999). Clinically Oriented Anatomy (4th ed.). p. 974. ISBN 0-683-06141-0.

- The Kingfisher children's encyclopedia. Kingfisher Publications. (3rd ed., fully rev. and updated ed.). New York: Kingfisher. 2012 [2011]. ISBN 9780753468142. OCLC 796083112.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Guenter Ehret (Dec 1978). "Stiffness gradient along the basilar membrane as a way for spatial frequency analysis within the cochlea" (PDF). J Acoust Soc Am. 64 (6): 1723–6. doi:10.1121/1.382153. PMID 739099.

- Camhi, J. Neuroethology: nerve cells and the natural behavior of animals. Sinauer Associates, 1984.

- Manoussaki D, Chadwick RS, Ketten DR, Arruda J, Dimitriadis EK, O'Malley JT (2008). "The influence of cochlear shape on low-frequency hearing". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 105 (16): 6162–6166. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.6162M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0710037105. PMC 2299218. PMID 18413615.

- Ashmore, Jonathan Felix (1987). "A fast motile response in guinea-pig outer hair cells: the cellular basis of the cochlear amplifier". The Journal of Physiology. 388 (1): 323–347. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016617. ISSN 1469-7793. PMC 1192551. PMID 3656195.

- Ashmore, Jonathan (2008). "Cochlear Outer Hair Cell Motility". Physiological Reviews. 88 (1): 173–210. doi:10.1152/physrev.00044.2006. ISSN 0031-9333. PMID 18195086. S2CID 17722638.

- Zhao, H. -B.; Kikuchi, T.; Ngezahayo, A.; White, T. W. (2006). "Gap Junctions and Cochlear Homeostasis". Journal of Membrane Biology. 209 (2–3): 177–186. doi:10.1007/s00232-005-0832-x. PMC 1609193. PMID 16773501.

- Erbe, C. B.; Harris, K. C.; Runge-Samuelson, C. L.; Flanary, V. A.; Wackym, P. A. (2004). "Connexin 26 and Connexin 30 Mutations in Children with Nonsyndromic Hearing Loss". The Laryngoscope. 114 (4): 607–611. doi:10.1097/00005537-200404000-00003. PMID 15064611. S2CID 25847431.

- Kikuchi, T.; Kimura, R. S.; Paul, D. L.; Takasaka, T.; Adams, J. C. (2000). "Gap junction systems in the mammalian cochlea". Brain Research. Brain Research Reviews. 32 (1): 163–166. doi:10.1016/S0165-0173(99)00076-4. PMID 10751665. S2CID 11292387.

- Kikuchi, T.; Kimura, R. S.; Paul, D. L.; Adams, J. C. (1995). "Gap junctions in the rat cochlea: Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural analysis". Anatomy and Embryology. 191 (2): 101–118. doi:10.1007/BF00186783. PMID 7726389. S2CID 24900775.

- Anne Trafton (June 3, 2009). "Drawing inspiration from nature to build a better radio: New radio chip mimics human ear, could enable universal radio". MIT newsoffice.

- Soumyajit Mandal; Serhii M. Zhak; Rahul Sarpeshkar (June 2009). "A Bio-Inspired Active Radio-Frequency Silicon Cochlea" (PDF). IEEE Journal of Solid-State Circuits. 44 (6): 1814–1828. Bibcode:2009IJSSC..44.1814M. doi:10.1109/JSSC.2009.2020465. hdl:1721.1/59982. S2CID 10756707.

- Vater M, Meng J, Fox RC. Hearing organ evolution and specialization: Early and later mammals. In: GA Manley, AN Popper, RR Fay (Eds). Evolution of the Vertebrate Auditory System, Springer-Verlag, New York 2004, pp 256–288.

- etymology of "cochleㄷa",

Further reading

- Dallos, Peter; Popper, Arthur N.; Fay, Richard R. The Cochlea.

- Imbert, Michel; Kay, R. H. (1992). Audition. ISBN 9780262023313.

- Jahn, Anthony F.; Santos-Sacchi, Joseph (2001). Physiology of the Ear. ISBN 9781565939943.

- Roeser, Ross J.; Valente, Michael; Hosford-Dunn, Holly (2007). Audiology. ISBN 9781588905420.

External links

- Cochlea at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- "Promenade 'Round the Cochlea" by R. Pujol, S. Blatrix, T. Pujol et al. at University of Montpellier

- "Histology Videos of The Ear"