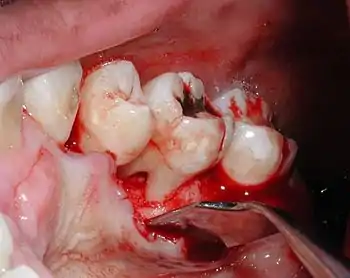

Furcation defect

In dentistry, a furcation defect is bone loss, usually a result of periodontal disease, affecting the base of the root trunk of a tooth where two or more roots meet (bifurcation or trifurcation). The extent and configuration of the defect are factors in both diagnosis and treatment planning.[1]

A tooth with a furcation defect typically possessed a more diminished prognosis owing to the difficulty of rendering the furcation area free from periodontal pathogens. For this reason, surgical periodontal treatment may be considered to either close the furcation defect with grafting procedures or allow greater access to the furcation defect for improved oral hygiene.

Root trunk length

The distance between the cementoenamel junction (CEJ) and the furcation entrance is called the root trunk length. This distance plays an important role in furcation defects because the deeper the furcation entrance is within the bone, the more bone loss necessary before the furcation becomes exposed.

For mandibular first molars, the mean root trunk length is 3 mm on the buccal aspect and 4 mm on the lingual aspect.[2] The root trunk lengths for mandibular second and third molars are either the same or slightly greater than for first molars, although the roots may be fused.

For maxillary first molars, the mean root trunk length is 3-4 mm on the buccal aspect, and 4-5 mm on the mesial aspect and 5-6 mm on the distal aspect.[2] As with mandibular molars, the root trunk lengths for maxillary second and third molars are either the same or slightly greater than for first molars, although the roots may be fused.

For maxillary first premolars, there is a bifurcation 40% of the time and the mean root trunk length is 8 mm from both mesial and distal.[2]

Furcation defect classification

Because of its importance in the assessment of periodontal disease, a number of methods of classification have evolved to measure and record the severity of furcation involvement; most of the indices are based on horizontal measurements of attachment loss in the furcation.

In 1953, Irving Glickman graded furcation involvement into the following four classes:[3]

- Grade I - Incipient furcation involvement, with an associated periodontal pocket remaining coronal to the alveolar bone. The pocket primarily affects the soft tissue. Early bone loss may have occurred but is rarely evident radiographically.

- Grade II - There is a definite horizontal component to the bone loss between roots resulting in a probeable area, but sufficient bone still remains attached to the tooth (at the dome of the furcation) so that multiple areas of furcal bone loss, if present, do not communicate.

- Grade III - Bone is no longer attached to the furcation of the tooth, essentially resulting in a through-and-through tunnel. Because of an angle in this tunnel, however, the furcation may not be able to be probed in its entirety; if cumulative measurements from different sides equal or exceed the width of the tooth, however, a grade III defect may be assumed. In early grade III lesions, soft tissue may still occlude the furcation involvement, thus, making it difficult to detect.

- Grade IV - Essentially a super grade III lesion, grade IV describes a through-and-through lesion that has sustained enough bone loss to make it completely probeable.

In 2000, Fedi, et al. modified Glickman's classification to include two degrees of a grade II furcation defect:[4]

- Grade II degree I - exists when furcal bone loss possesses a vertical component of >1 but <3mm.

- Grade II degree II - exists when furcal bone loss possesses a vertical component of >3mm, but still does not communicate through-and-through.

In 1975, Sven-Erik Hamp, together with Lindhe and Sture Nyman, classified furcation defects by their probeable depth.

- Class I - Furcation defect is less than 3 mm in depth.

- Class II - Furcation defect is at least 3 mm in depth (and thus, in general, surpassing half of the buccolingual thickness of the tooth) but not through-and-through (i.e. there is still some interradicular bone attached to the angle of the furcation. The furcation defect is thus a cul-de-sac.

- Class III - Furcation defect encompassing the entire width of the tooth so that no bone is attached to the angle of the furcation.[4]

Diagnosis

Nabers probe is used to check for furcation involvement clinically. Recently, cone beam computerised technology (CBCT) has also be used to detect furcation.[5] Periapical and interproximal intraoral radiographs can help diagnosing and locating the furcation.

Only multirooted teeth have furcation. Therefore, upper first premolar, maxillary and mandibular molars may be involved. Upper premolars have one buccal and one palatal root. Maxillary molars have three roots, a mesio-buccal root, disto-buccal root and a palatal root. Mandibular molars have one mesial and one distal root, and so.

Treatment

The treatment aims are to eliminate the bacteria from the exposed surface of the root(s) and to establish the anatomy of the tooth, so that better plaque control can be achieved. Treatment plans for patients differ depending on the local and anatomical factors.

For Grade I furcation, scaling and polishing,[5][6] root surface debridement or furcationplasty could be done if suitable.

For Grade II furcation, furcationplasty, open debridement,[5][7] tunnel preparation,[5] root resection,[5] extraction,[5] guided tissue regeneration (GTR)[7][5][6] or enamel matrix derivative could be considered.

As for Grade III furcation, open debridement,[5][7] tunnel preparation,[5] root resection,[5][6] GTR,[7][5] or tooth extraction[5] could be performed if appropriate.

Tooth extraction is usually considered if there is extensive loss of attachment or if other treatments will not obtain good result (i.e. achieving a nice gingival contour to allow good plaque control).

References

- Ammons WF, Harrington GW: Furcation, The Problem and Its Management. In Newman, Takei, Carranza, editors: Carranza's Clinical Periodontology, 9th Edition. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co. 2002. page 826-7.

- Carnavale F, Pontoriero R, Lindhe, J: Treatment of Furcation-Involved Teeth. In Lindhe, Karring, Lang, editors: Clinical Periodontology and Implant Dentistry, 4th Edition. London: Blackwell Munksgaard. 2003. pages 707-8.

- Knowles J, Burgett F, Nissle R: Results of periodontal treatment related to pocket depth and attachment level, Eight years. J Perio 1979; 50:225.

- Vandersall DC: Concise Encyclopedia of Periodontology Blackwell Munksgaard 2007

- Umetsubo, Otavio Shoiti; Gaia, Bruno Felipe; Costa, Felipe Ferreira; Cavalcanti, Marcelo Gusmão Paraiso (2012-08-01). "Detection of simulated incipient furcation involvement by CBCT: an in vitro study using pig mandibles". Brazilian Oral Research. 26 (4): 341–347. doi:10.1590/S1806-83242012000400010. ISSN 1806-8324. PMID 22790499.

- "Treatment of Furcation Defects". www.drbui.com. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- Aichelmann-Reidy, Mary E.; Avila-Ortiz, Gustavo; Klokkevold, Perry R.; Murphy, Kevin G.; Rosen, Paul S.; Schallhorn, Robert G.; Sculean, Anton; Wang, Hom-Lay; Reddy, Michael S. (2015). "Periodontal Regeneration — Furcation Defects: Practical Applications From the AAP Regeneration Workshop" (PDF). Clinical Advances in Periodontics. 5 (1): 30–39. doi:10.1902/cap.2015.140068. hdl:2027.42/141344.