Heredity

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic information of their parents. Through heredity, variations between individuals can accumulate and cause species to evolve by natural selection. The study of heredity in biology is genetics.

| Part of a series on |

| Genetics |

|---|

|

|

Overview

In humans, eye color is an example of an inherited characteristic: an individual might inherit the "brown-eye trait" from one of the parents.[1] Inherited traits are controlled by genes and the complete set of genes within an organism's genome is called its genotype.[2]

The complete set of observable traits of the structure and behavior of an organism is called its phenotype. These traits arise from the interaction of its genotype with the environment.[3] As a result, many aspects of an organism's phenotype are not inherited. For example, suntanned skin comes from the interaction between a person's genotype and sunlight;[4] thus, suntans are not passed on to people's children. However, some people tan more easily than others, due to differences in their genotype:[5] a striking example is people with the inherited trait of albinism, who do not tan at all and are very sensitive to sunburn.[6]

Heritable traits are known to be passed from one generation to the next via DNA, a molecule that encodes genetic information.[2] DNA is a long polymer that incorporates four types of bases, which are interchangeable. The Nucleic acid sequence (the sequence of bases along a particular DNA molecule) specifies the genetic information: this is comparable to a sequence of letters spelling out a passage of text.[7] Before a cell divides through mitosis, the DNA is copied, so that each of the resulting two cells will inherit the DNA sequence. A portion of a DNA molecule that specifies a single functional unit is called a gene; different genes have different sequences of bases. Within cells, the long strands of DNA form condensed structures called chromosomes. Organisms inherit genetic material from their parents in the form of homologous chromosomes, containing a unique combination of DNA sequences that code for genes. The specific location of a DNA sequence within a chromosome is known as a locus. If the DNA sequence at a particular locus varies between individuals, the different forms of this sequence are called alleles. DNA sequences can change through mutations, producing new alleles. If a mutation occurs within a gene, the new allele may affect the trait that the gene controls, altering the phenotype of the organism.[8]

However, while this simple correspondence between an allele and a trait works in some cases, most traits are more complex and are controlled by multiple interacting genes within and among organisms.[9][10] Developmental biologists suggest that complex interactions in genetic networks and communication among cells can lead to heritable variations that may underlie some of the mechanics in developmental plasticity and canalization.[11]

Recent findings have confirmed important examples of heritable changes that cannot be explained by direct agency of the DNA molecule. These phenomena are classed as epigenetic inheritance systems that are causally or independently evolving over genes. Research into modes and mechanisms of epigenetic inheritance is still in its scientific infancy, but this area of research has attracted much recent activity as it broadens the scope of heritability and evolutionary biology in general.[12] DNA methylation marking chromatin, self-sustaining metabolic loops, gene silencing by RNA interference, and the three dimensional conformation of proteins (such as prions) are areas where epigenetic inheritance systems have been discovered at the organismic level.[13][14] Heritability may also occur at even larger scales. For example, ecological inheritance through the process of niche construction is defined by the regular and repeated activities of organisms in their environment. This generates a legacy of effect that modifies and feeds back into the selection regime of subsequent generations. Descendants inherit genes plus environmental characteristics generated by the ecological actions of ancestors.[15] Other examples of heritability in evolution that are not under the direct control of genes include the inheritance of cultural traits, group heritability, and symbiogenesis.[16][17][18] These examples of heritability that operate above the gene are covered broadly under the title of multilevel or hierarchical selection, which has been a subject of intense debate in the history of evolutionary science.[17][19]

Relation to theory of evolution

When Charles Darwin proposed his theory of evolution in 1859, one of its major problems was the lack of an underlying mechanism for heredity.[20] Darwin believed in a mix of blending inheritance and the inheritance of acquired traits (pangenesis). Blending inheritance would lead to uniformity across populations in only a few generations and then would remove variation from a population on which natural selection could act.[21] This led to Darwin adopting some Lamarckian ideas in later editions of On the Origin of Species and his later biological works.[22] Darwin's primary approach to heredity was to outline how it appeared to work (noticing that traits that were not expressed explicitly in the parent at the time of reproduction could be inherited, that certain traits could be sex-linked, etc.) rather than suggesting mechanisms.

Darwin's initial model of heredity was adopted by, and then heavily modified by, his cousin Francis Galton, who laid the framework for the biometric school of heredity.[23] Galton found no evidence to support the aspects of Darwin's pangenesis model, which relied on acquired traits.[24]

The inheritance of acquired traits was shown to have little basis in the 1880s when August Weismann cut the tails off many generations of mice and found that their offspring continued to develop tails.[25]

History

Scientists in Antiquity had a variety of ideas about heredity: Theophrastus proposed that male flowers caused female flowers to ripen;[26] Hippocrates speculated that "seeds" were produced by various body parts and transmitted to offspring at the time of conception;[27] and Aristotle thought that male and female fluids mixed at conception.[28] Aeschylus, in 458 BC, proposed the male as the parent, with the female as a "nurse for the young life sown within her".[29]

Ancient understandings of heredity transitioned to two debated doctrines in the 18th century. The Doctrine of Epigenesis and the Doctrine of Preformation were two distinct views of the understanding of heredity. The Doctrine of Epigenesis, originated by Aristotle, claimed that an embryo continually develops. The modifications of the parent's traits are passed off to an embryo during its lifetime. The foundation of this doctrine was based on the theory of inheritance of acquired traits. In direct opposition, the Doctrine of Preformation claimed that "like generates like" where the germ would evolve to yield offspring similar to the parents. The Preformationist view believed procreation was an act of revealing what had been created long before. However, this was disputed by the creation of the cell theory in the 19th century, where the fundamental unit of life is the cell, and not some preformed parts of an organism. Various hereditary mechanisms, including blending inheritance were also envisaged without being properly tested or quantified, and were later disputed. Nevertheless, people were able to develop domestic breeds of animals as well as crops through artificial selection. The inheritance of acquired traits also formed a part of early Lamarckian ideas on evolution.

During the 18th century, Dutch microscopist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (1632–1723) discovered "animalcules" in the sperm of humans and other animals.[30] Some scientists speculated they saw a "little man" (homunculus) inside each sperm. These scientists formed a school of thought known as the "spermists". They contended the only contributions of the female to the next generation were the womb in which the homunculus grew, and prenatal influences of the womb.[31] An opposing school of thought, the ovists, believed that the future human was in the egg, and that sperm merely stimulated the growth of the egg. Ovists thought women carried eggs containing boy and girl children, and that the gender of the offspring was determined well before conception.[32]

An early research initiative emerged in 1878 when Alpheus Hyatt led an investigation to study the laws of heredity through compiling data on family phenotypes (nose size, ear shape, etc.) and expression of pathological conditions and abnormal characteristics, particularly with respect to the age of appearance. One of the projects aims was to tabulate data to better understand why certain traits are consistently expressed while others are highly irregular.[33]

Gregor Mendel: father of genetics

The idea of particulate inheritance of genes can be attributed to the Moravian[34] monk Gregor Mendel who published his work on pea plants in 1865. However, his work was not widely known and was rediscovered in 1901. It was initially assumed that Mendelian inheritance only accounted for large (qualitative) differences, such as those seen by Mendel in his pea plants – and the idea of additive effect of (quantitative) genes was not realised until R.A. Fisher's (1918) paper, "The Correlation Between Relatives on the Supposition of Mendelian Inheritance" Mendel's overall contribution gave scientists a useful overview that traits were inheritable. His pea plant demonstration became the foundation of the study of Mendelian Traits. These traits can be traced on a single locus.[35]

Modern development of genetics and heredity

In the 1930s, work by Fisher and others resulted in a combination of Mendelian and biometric schools into the modern evolutionary synthesis. The modern synthesis bridged the gap between experimental geneticists and naturalists; and between both and palaeontologists, stating that:[36][37]

- All evolutionary phenomena can be explained in a way consistent with known genetic mechanisms and the observational evidence of naturalists.

- Evolution is gradual: small genetic changes, recombination ordered by natural selection. Discontinuities amongst species (or other taxa) are explained as originating gradually through geographical separation and extinction (not saltation).

- Selection is overwhelmingly the main mechanism of change; even slight advantages are important when continued. The object of selection is the phenotype in its surrounding environment. The role of genetic drift is equivocal; though strongly supported initially by Dobzhansky, it was downgraded later as results from ecological genetics were obtained.

- The primacy of population thinking: the genetic diversity carried in natural populations is a key factor in evolution. The strength of natural selection in the wild was greater than expected; the effect of ecological factors such as niche occupation and the significance of barriers to gene flow are all important.

The idea that speciation occurs after populations are reproductively isolated has been much debated.[38] In plants, polyploidy must be included in any view of speciation. Formulations such as 'evolution consists primarily of changes in the frequencies of alleles between one generation and another' were proposed rather later. The traditional view is that developmental biology ('evo-devo') played little part in the synthesis, but an account of Gavin de Beer's work by Stephen Jay Gould suggests he may be an exception.[39]

Almost all aspects of the synthesis have been challenged at times, with varying degrees of success. There is no doubt, however, that the synthesis was a great landmark in evolutionary biology.[40] It cleared up many confusions, and was directly responsible for stimulating a great deal of research in the post-World War II era.

Trofim Lysenko however caused a backlash of what is now called Lysenkoism in the Soviet Union when he emphasised Lamarckian ideas on the inheritance of acquired traits. This movement affected agricultural research and led to food shortages in the 1960s and seriously affected the USSR.[41]

There is growing evidence that there is transgenerational inheritance of epigenetic changes in humans[42] and other animals.[43]

Common genetic disorders

Types

The description of a mode of biological inheritance consists of three main categories:

- 1. Number of involved loci

- Monogenetic (also called "simple") – one locus

- Oligogenic – few loci

- Polygenetic – many loci

- 2. Involved chromosomes

- Autosomal – loci are not situated on a sex chromosome

- Gonosomal – loci are situated on a sex chromosome

- X-chromosomal – loci are situated on the X-chromosome (the more common case)

- Y-chromosomal – loci are situated on the Y-chromosome

- Mitochondrial – loci are situated on the mitochondrial DNA

- 3. Correlation genotype–phenotype

- Dominant

- Intermediate (also called "codominant")

- Recessive

- Overdominant

- Underdominant

These three categories are part of every exact description of a mode of inheritance in the above order. In addition, more specifications may be added as follows:

- 4. Coincidental and environmental interactions

- Penetrance

- Complete

- Incomplete (percentual number)

- Expressivity

- Invariable

- Variable

- Heritability (in polygenetic and sometimes also in oligogenetic modes of inheritance)

- Maternal or paternal imprinting phenomena (also see epigenetics)

- Penetrance

- 5. Sex-linked interactions

- Sex-linked inheritance (gonosomal loci)

- Sex-limited phenotype expression (e.g., cryptorchism)

- Inheritance through the maternal line (in case of mitochondrial DNA loci)

- Inheritance through the paternal line (in case of Y-chromosomal loci)

- 6. Locus–locus interactions

- Epistasis with other loci (e.g., overdominance)

- Gene coupling with other loci (also see crossing over)

- Homozygotous lethal factors

- Semi-lethal factors

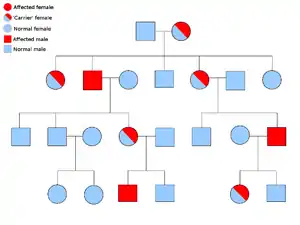

Determination and description of a mode of inheritance is also achieved primarily through statistical analysis of pedigree data. In case the involved loci are known, methods of molecular genetics can also be employed.

Dominant and recessive alleles

An allele is said to be dominant if it is always expressed in the appearance of an organism (phenotype) provided that at least one copy of it is present. For example, in peas the allele for green pods, G, is dominant to that for yellow pods, g. Thus pea plants with the pair of alleles either GG (homozygote) or Gg (heterozygote) will have green pods. The allele for yellow pods is recessive. The effects of this allele are only seen when it is present in both chromosomes, gg (homozygote). This derives from Zygosity, the degree to which both copies of a chromosome or gene have the same genetic sequence, in other words, the degree of similarity of the alleles in an organism.

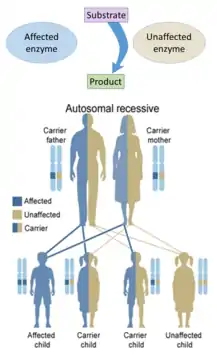

Hereditary defects in enzymes are generally inherited in an autosomal fashion because there are more non-X chromosomes than X-chromosomes, and a recessive fashion because the enzymes from the unaffected genes are generally sufficient to prevent symptoms in carriers.

Hereditary defects in enzymes are generally inherited in an autosomal fashion because there are more non-X chromosomes than X-chromosomes, and a recessive fashion because the enzymes from the unaffected genes are generally sufficient to prevent symptoms in carriers. On the other hand, hereditary defects in structural proteins (such as osteogenesis imperfecta, Marfan's syndrome and many Ehlers–Danlos syndromes) are generally autosomal dominant, because it is enough that some components are defective to make the whole structure dysfunctional. This is a dominant-negative process, wherein a mutated gene product adversely affects the non-mutated gene product within the same cell.

On the other hand, hereditary defects in structural proteins (such as osteogenesis imperfecta, Marfan's syndrome and many Ehlers–Danlos syndromes) are generally autosomal dominant, because it is enough that some components are defective to make the whole structure dysfunctional. This is a dominant-negative process, wherein a mutated gene product adversely affects the non-mutated gene product within the same cell.

See also

- Hard inheritance

- Lamarckism

- Heritability

- Particulate inheritance

- Non-Mendelian inheritance

- Extranuclear inheritance

- Uniparental inheritance

- Epigenetic inheritance

- Transgenerational epigenetics#Major controversies in the history of inheritance

- Inheritance of acquired characteristics

- Structural inheritance

- Blending inheritance

References

- Sturm RA; Frudakis TN (2004). "Eye colour: portals into pigmentation genes and ancestry". Trends Genet. 20 (8): 327–332. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2004.06.010. PMID 15262401.

- Pearson H (2006). "Genetics: what is a gene?". Nature. 441 (7092): 398–401. Bibcode:2006Natur.441..398P. doi:10.1038/441398a. PMID 16724031. S2CID 4420674.

- Visscher PM; Hill WG; Wray NR (2008). "Heritability in the genomics era – concepts and misconceptions". Nat. Rev. Genet. 9 (4): 255–266. doi:10.1038/nrg2322. PMID 18319743. S2CID 690431.

- Shoag J; et al. (Jan 2013). "PGC-1 coactivators regulate MITF and the tanning response". Mol Cell. 49 (1): 145–157. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.027. PMC 3753666. PMID 23201126.

- Pho LN; Leachman SA (Feb 2010). "Genetics of pigmentation and melanoma predisposition". G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 145 (1): 37–45. PMID 20197744. Archived from the original on 2019-03-28. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- Oetting WS; Brilliant MH; King RA (1996). "The clinical spectrum of albinism in humans and by action". Molecular Medicine Today. 2 (8): 330–335. doi:10.1016/1357-4310(96)81798-9. PMID 8796918.

- Griffiths, Anthony, J.F.; Wessler, Susan R.; Carroll, Sean B.; Doebley J (2012). Introduction to Genetic Analysis (10th ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-4292-2943-2.

- Futuyma, Douglas J. (2005). Evolution. Sunderland, Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates, Inc. ISBN 978-0-87893-187-3.

- Phillips PC (2008). "Epistasis – the essential role of gene interactions in the structure and evolution of genetic systems". Nat. Rev. Genet. 9 (11): 855–867. doi:10.1038/nrg2452. PMC 2689140. PMID 18852697.

- Wu R; Lin M (2006). "Functional mapping – how to map and study the genetic architecture of dynamic complex traits". Nat. Rev. Genet. 7 (3): 229–237. doi:10.1038/nrg1804. PMID 16485021. S2CID 24301815.

- Jablonka, E.; Lamb, M.J. (2002). "The changing concept of epigenetics" (PDF). Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 981 (1): 82–96. Bibcode:2002NYASA.981...82J. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04913.x. PMID 12547675. S2CID 12561900. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-05-11.

- Jablonka, E.; Raz, G. (2009). "Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance: Prevalence, mechanisms, and implications for the study of heredity and evolution" (PDF). The Quarterly Review of Biology. 84 (2): 131–176. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.617.6333. doi:10.1086/598822. PMID 19606595. S2CID 7233550. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-07-15. Retrieved 2011-02-18.

- Bossdorf, O.; Arcuri, D.; Richards, C.L.; Pigliucci, M. (2010). "Experimental alteration of DNA methylation affects the phenotypic plasticity of ecologically relevant traits in Arabidopsis thaliana" (PDF). Evolutionary Ecology. 24 (3): 541–553. doi:10.1007/s10682-010-9372-7. S2CID 15763479. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-03-01. Retrieved 2019-08-15.

- Jablonka, E.; Lamb, M. (2005). Evolution in four dimensions: Genetic, epigenetic, behavioural, and symbolic. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-10107-3. Archived from the original on 2021-12-27. Retrieved 2015-06-27.

- Laland, K.N.; Sterelny, K. (2006). "Perspective: Seven reasons (not) to neglect niche construction". Evolution. 60 (8): 1751–1762. doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2006.tb00520.x. PMID 17089961.

- Chapman, M.J.; Margulis, L. (1998). "Morphogenesis by symbiogenesis" (PDF). International Microbiology. 1 (4): 319–326. PMID 10943381. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-08-23.

- Wilson, D. S.; Wilson, E.O. (2007). "Rethinking the theoretical foundation of sociobiology" (PDF). The Quarterly Review of Biology. 82 (4): 327–348. doi:10.1086/522809. PMID 18217526. S2CID 37774648. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-05-11.

- Bijma, P.; Wade, M.J. (2008). "The joint effects of kin, multilevel selection and indirect genetic effects on response to genetic selection". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 21 (5): 1175–1188. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01550.x. PMID 18547354. S2CID 7204089.

- Vrba, E.S.; Gould, S.J. (1986). "The hierarchical expansion of sorting and selection: Sorting and selection cannot be equated" (PDF). Paleobiology. 12 (2): 217–228. doi:10.1017/S0094837300013671. S2CID 86593897. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-08-04. Retrieved 2011-02-18.

- Griffiths, Anthony, J.F.; Wessler, Susan R.; Carroll, Sean B.; Doebley, John (2012). Introduction to Genetic Analysis (10th ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-4292-2943-2.

- Charlesworth, Brian & Charlesworth, Deborah (November 2009). "Darwin and Genetics". Genetics. 183 (3): 757–766. doi:10.1534/genetics.109.109991. PMC 2778973. PMID 19933231. Archived from the original on 2019-04-29. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- Bard, Jonathan BL (2011). "The next evolutionary synthesis: from Lamarck and Darwin to genomic variation and systems biology". Cell Communication and Signaling. 9 (30): 30. doi:10.1186/1478-811X-9-30. PMC 3215633. PMID 22053760.

- "Francis Galton (1822-1911)". Science Museum. Archived from the original on January 30, 2016. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- Liu Y. (May 2008). "A new perspective on Darwin's Pangenesis". Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 83 (2): 141–149. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2008.00036.x. PMID 18429766. S2CID 39953275.

- Lipton, Bruce H. (2008). The Biology of Belief: Unleashing the Power of Consciousness, Matter and Miracles. Hay House, Inc. pp. 12. ISBN 978-1-4019-2344-0.

- Negbi, Moshe (Summer 1995). "Male and female in Theophrastus's botanical works". Journal of the History of Biology. 28 (2): 317–332. doi:10.1007/BF01059192. S2CID 84754865.

- Hipócrates (1981). Hippocratic Treatises: On Generation – Nature of the Child – Diseases Ic. Walter de Gruyter. p. 6. ISBN 978-3-11-007903-6.

- "Aristotle's Biology – 5.2. From Inquiry to Understanding; from hoti to dioti". Stanford University. Feb 15, 2006. Archived from the original on May 7, 2019. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- Eumenides 658-661

- Snow, Kurt. "Antoni van Leeuwenhoek's Amazing Little "Animalcules"". Leben. Archived from the original on April 24, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- Lawrence, Cera R. (2008). Hartsoeker's Homunculus Sketch from Essai de Dioptrique. Embryo Project Encyclopedia. ISSN 1940-5030. Archived from the original on 2013-04-09. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- Gottlieb, Gilbert (2001). Individual Development and Evolution: The Genesis of Novel Behavior. Psychology Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-4106-0442-2.

- Scientific American, "Heredity". Munn & Company. 1878-11-30. p. 343. Archived from the original on 2022-05-18. Retrieved 2021-08-06.

- Henig, Robin Marantz (2001). The Monk in the Garden : The Lost and Found Genius of Gregor Mendel, the Father of Genetics. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-97765-1.

The article, written by an obscure Moravian monk named Gregor Mendel

- Carlson, Neil R. (2010). Psychology: the Science of Behavior, p. 206. Toronto: Pearson Canada. ISBN 978-0-205-64524-4. OCLC 1019975419

- Mayr & Provine 1998

- Mayr E. 1982. The growth of biological thought: diversity, evolution & inheritance. Harvard, Cambs. pp. 567 et seq.

- Palumbi, Stephen R. (1994). "Genetic Divergence, Reproductive Isolation, and Marine Speciation". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 25: 547–572. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.25.110194.002555.

- Gould S.J. Ontogeny and phylogeny. Harvard 1977. pp. 221–222

- Handschuh, Stephan; Mitteroecker, Philipp (June 2012). "Evolution – The Extended Synthesis. A research proposal persuasive enough for the majority of evolutionary biologists?". Human Ethology Bulletin. 27 (1–2): 18–21. ISSN 2224-4476.

- Harper, Peter S. (2017-08-03). "Human genetics in troubled times and places". Hereditas. 155: 7. doi:10.1186/s41065-017-0042-4. ISSN 1601-5223. PMC 5541658. PMID 28794693.

- Szyf, M (2015). "Nongenetic inheritance and transgenerational epigenetics". Trends in Molecular Medicine. 21 (2): 134–144. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2014.12.004. PMID 25601643.

- Kishimoto, S; et al. (2017). "Environmental stresses induce transgenerationally inheritable survival advantages via germline-to-soma communication in Caenorhabditis elegans". Nature Communications. 8: 14031. Bibcode:2017NatCo...814031K. doi:10.1038/ncomms14031. hdl:2433/217772. PMC 5227915. PMID 28067237.