Factor I deficiency

Factor I deficiency, also known as fibrinogen deficiency, is a rare inherited bleeding disorder related to fibrinogen function in the blood coagulation cascade. It is typically subclassified into four distinct fibrinogen disorders: afibrinogenemia, hypofibrinogenemia, dysfibrinogenemia, and hypodysfibrinogenemia.[1]

- Afibrinogenemia is defined as a lack of fibrinogen in the blood, clinically <20 mg/deciliter of plasma. The frequency of this disorder is estimated at between 0.5 and 2 per million.[2] Within the United States, afibrinogenemia accounts for 24% of all inherited abnormalities of fibrinogen, while hypofibrinogenemia and dysfibrinogenemia account for 38% each.[3]

- Congenital hypofibrinogenemia is defined as a partial deficiency of fibrinogen, clinically 20–80/deciliter of plasma. Estimated frequency varies from <0.5 to 3 per million.[2][3]

- Dysfibrinogenemia is defined as malfunctioning or non-functioning fibrinogen in the blood, albeit at normal concentrations: 200–400 mg/deciliter of plasma. Dysfibrinogenemia may be an inherited disease and therefore termed congenital dysfibrinogenemia or secondary to another disease and therefore termed acquired dysfibrinogenemia. The congenital disorder is estimated to a frequency varying between 1 and 3 per million.[2][3][4]

- Hypodysfibrinogenemia is a partial deficiency of fibrinogen that is also malfunctioning. Hypodysfibrinogenemia is an extremely rare inherited disease.[5]

| Factor I deficiency | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Immunodeficiency with factor I anomaly |

| |

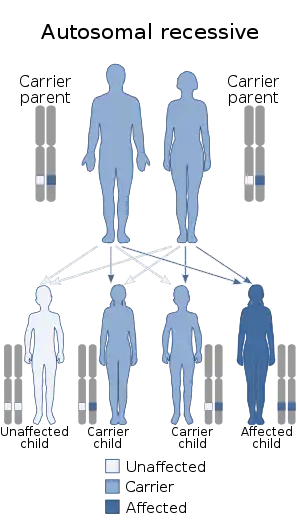

| Factor I deficiency is inherited in an autosomal recessive (shown above) or autosomal dominant manner. | |

Clinically, these disorders are generally associated with an increased diathesis, i.e. propensity, to develop spontaneous bleeding episodes and excessive bleeding after even minor tissue injuries and surgeries; however, individuals with any of these disorders may also exhibit a propensity to pathological thrombosis episodes.[4][6]

Treatment of these disorders generally involves specialized centers and the establishment of preventive measures designed based on each individuals personal and family histories of the frequency and severity of previous bleeding and thrombosis episodes, and, in a select few cases, the predicted propensity of the genetic mutations which underlie their disorders to cause bleeding and thrombosis.[5][6]

Signs and symptoms

Afibrinogenemia is typically the most severe of the three disorders. Common symptoms include bleeding of the umbilical cord at birth, traumatic and surgical bleeding, GI tract, oral and mucosal bleeding, spontaneous splenic rupture, and rarely intracranial hemorrhage and articular bleeding.[2][7] Symptoms of hypofibrinogenemia varies from mild to severe, but can include bleeding of the GI tract, oral and mucosal bleeding, and very rarely intracranial bleeding. More commonly it presents during traumatic bleeding or surgical procedures.[2][3] Most cases (60%) of dysfibrinogenemia are asymptomatic, but 28% exhibit hemorrhaging similar to that described above while 20% exhibit thrombosis (i.e. excessive clotting).[3]

Causes

The disorders associated with Factor I deficiency are generally inherited,[2][3] although certain liver diseases can also affect fibrinogen levels and function (e.g. cirrhosis).[8] Afibrinogenemia is a recessive inherited disorder, where both parents must be carriers.[2] Hypofibrinogenemia and dysfibrinogenemia can be dominant (i.e. only one parent needs to be a carrier) or recessive.[2] The origin of the disorders is traced back to three possible genes: FGA, FGB, or FGG. Because all three are involved in forming the hexameric glycoprotein fibrinogen, mutations in any one of the three genes can cause the deficiency.[9][10]

Diagnosis

Treatment

The most common type of treatment is cryoprecipitate or fibrinogen concentrate drip to increase fibrinogen levels to normal during surgical procedures or after trauma.[11][2] RiaSTAP, a factor I concentrate, was approved by the U.S. FDA in 2009 for use when the fibrinogen level was below 50 mg/deciliter of plasma.[12] Recently, antifibrinolytics have also been used to inhibit fibrinolysis (breaking down of the fibrin clot).[3] In the case of dysfibrinogenemia that manifests by thrombosis, anticoagulants can be used.[2] Due to the inhibited clotting ability associated with a- and hypofibrinogenemia, physicians advise against the use of Aspirin as it inhibits platelet function.[2]

References

- "What is factor I (fibrinogen) deficiency?".

- "Factor I Deficiency".

- Acharya, Suchitra S (2019-02-02). Tebbi, Cameron K (ed.). "Inherited Abnormalities of Fibrinogen". medscape.com.

- Casini A, Neerman-Arbez M, Ariëns RA, de Moerloose P (2015). "Dysfibrinogenemia: from molecular anomalies to clinical manifestations and management". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 13 (6): 909–19. doi:10.1111/jth.12916. PMID 25816717.

- Casini A, Brungs T, Lavenu-Bombled C, Vilar R, Neerman-Arbez M, de Moerloose P (2017). "Genetics, diagnosis and clinical features of congenital hypodysfibrinogenemia: a systematic literature review and report of a novel mutation". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 15 (5): 876–888. doi:10.1111/jth.13655. PMID 28211264.

- Neerman-Arbez M, de Moerloose P, Casini A (2016). "Laboratory and Genetic Investigation of Mutations Accounting for Congenital Fibrinogen Disorders". Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis. 42 (4): 356–65. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1571340. PMID 27019463.

- C. Merskey; A. J. Johnson; G. J. Kleiner; H. Wohl (1967). "The Defibrination Syndrome: Clinical Features and Laboratory Diagnosis". British Journal of Haematology. Vol. 13. p. 528. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.1967.tb00762.x.

- Jody L. Kujovich. "Hemostatic Defects in End Stage Liver Disease" (PDF). Critical Care Clinics. Vol. 21. p. 563. doi:10.1016/j.ccc.2005.03.002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-12-02.

- "Congenital Fibrinogen Deficiency via the FGB Gene". Archived from the original on 2014-10-31.

- Acharya SS, Dimichele DM (2008). "Rare inherited disorders of fibrinogen". Haemophilia. 14 (6): 1151–8. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2516.2008.01831.x. PMID 19141154.

- "Rare Clotting Factor Deficiencies (Treatment options)".

- "Factor I". 2014-03-05.