Iliopsoas

The iliopsoas muscle (/ˌɪlioʊˈsoʊ.əs/; from Latin: ile, lit. 'groin' and Ancient Greek: ψόᾱ, romanized: psóā, lit. 'muscles of the loins') refers to the joined psoas major and the iliacus muscles. The two muscles are separate in the abdomen, but usually merge in the thigh. They are usually given the common name iliopsoas. The iliopsoas muscle joins to the femur at the lesser trochanter. It acts as the strongest flexor of the hip.

| Iliopsoas | |

|---|---|

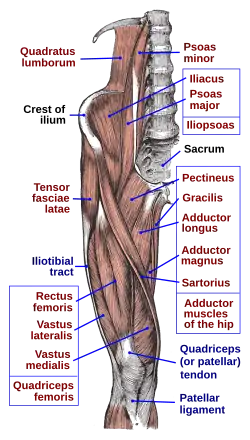

Anterior hip and thigh muscles. | |

| Details | |

| Origin | Iliac fossa and lumbar spine |

| Insertion | Lesser trochanter of femur |

| Artery | Medial femoral circumflex artery and iliolumbar artery |

| Nerve | Branches from L1 to L3 |

| Actions | Flexion of hip |

| Antagonist | Gluteus maximus and the posterior compartment of thigh |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Musculus iliopsoas |

| TA98 | A04.7.02.002 |

| TA2 | 2593 |

| FMA | 64918 |

| Anatomical terms of muscle | |

The iliopsoas muscle is supplied by the lumbar spinal nerves L1–L3 (psoas) and parts of the femoral nerve (iliacus).

Structure

The iliopsoas muscle is a composite muscle formed from the psoas major muscle, and the iliacus muscle. The psoas major originates along the outer surfaces of the vertebral bodies of T12 and L1–L3 and their associated intervertebral discs.[1] The iliacus originates in the iliac fossa of the pelvis.[2]

The psoas major unites with the iliacus at the level of the inguinal ligament. It crosses the hip joint to insert on the lesser trochanter of the femur.[1] The iliopsoas is classified as an "anterior hip muscle" or "inner hip muscle".[2] The psoas minor does contribute to the iliopsoas muscle.

The inferior portion below the inguinal ligament forms part of the floor of the femoral triangle.

Nerve supply

The psoas major is innervated by direct branches of the anterior rami of the lumbar plexus at the levels of L1–L3, while the iliacus is innervated by the femoral nerve (which is composed of nerves from the anterior rami of L2–L4).

Function

The iliopsoas is the prime mover of hip flexion, and is the strongest of the hip flexors (others are rectus femoris, sartorius, and tensor fasciae latae).[3] The iliopsoas is important for standing, walking, and running.[2] The iliacus and psoas major perform different actions when postural changes occur.

The iliopsoas muscle is covered by the iliac fascia, which begins as a strong tube-shaped psoas fascia, which surround the psoas major muscle as it passes under the medial arcuate ligament. Together with the iliac fascia, it continues down to the inguinal ligament where it forms the iliopectineal arch which separates the muscular and vascular lacunae.[4]

Clinical significance

It is a typical posture muscle dominated by slow-twitch red type 1 fibers. Since it originates from the lumbar vertebrae and discs and then inserts onto the femur, any structure from the lumbar spine to the femur can be affected directly. A short and tight iliopsoas often presents as externally rotated legs and feet. It can cause pain in the low or mid back, SI joint, hip, groin, thigh, knee, or any combination. The iliopsoas gets innervation from the L2-4 nerve roots of the lumbar plexus which also send branches to the superficial lumbar muscles. The femoral nerve passes through the muscle and innervates the quadriceps, pectineus, and sartorius muscles. It also comprises the intermediate femoral cutaneous and medial femoral cutaneous nerves which are responsible for sensation over the anterior and medial aspects of the thigh, medial shin, and arch of the foot nerves. The obturator nerve also passes through the muscle which is responsible for the sensory innervation of the skin of the medial aspect of the thigh and motor innervation of the adductor muscles of the lower extremity (external obturator, adductor longus, adductor brevis, adductor magnus, gracilis) and sometimes the pectineus. Any of these innervated structures can be affected.

Bleeding

Iliopsoas muscle is a common site of bleeding in patients who are undergoing blood anticoagulation.[5]

Additional images

Iliopsoas muscle

Iliopsoas muscle

See also

- Psoas abscess

- Iliopsoas tendonitis

- Muscles of the hip

- Dr. Ronald Conger

References

- Smith, Howard S.; Dubin, Andrew (2009-01-01), Argoff, Charles E.; McCleane, Gary (eds.), "Chapter 5 - Physical Examination of the Patient with Pain", Pain Management Secrets (Third Edition), Philadelphia: Mosby, pp. 32–41, doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-04019-8.00005-6, ISBN 978-0-323-04019-8, retrieved 2021-03-08

- Thieme Atlas of Anatomy. Thieme. 2006. pp. 422–423. ISBN 3131421010.

- Jelvéus, Anders (2011-01-01), Jelvéus, Anders (ed.), "14 - Soft tissue treatment techniques for maintenance and remedial sports massage", Integrated Sports Massage Therapy, Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, pp. 207–234, doi:10.1016/b978-0-443-10126-7.00014-9, ISBN 978-0-443-10126-7, retrieved 2021-03-08

- Platzer, Werner (2004). Color Atlas of Human Anatomy, Vol 1: Locomotor system (5th ed.). Thieme. p. 254. ISBN 3-13-533305-1.

- Federle, Michael P.; Rosado-de-Christenson, Melissa L.; Raman, Siva P.; Carter, Brett W., eds. (2017-01-01), "Abdominal Wall", Imaging Anatomy: Chest, Abdomen, Pelvis (Second Edition), Elsevier, pp. 484–507, doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-47781-9.50025-8, ISBN 978-0-323-47781-9, retrieved 2021-03-08

External links

- Cross section image: pelvis/pelvis-e12-15—Plastination Laboratory at the Medical University of Vienna