Medical imaging

Medical imaging is the technique and process of imaging the interior of a body for clinical analysis and medical intervention, as well as visual representation of the function of some organs or tissues (physiology). Medical imaging seeks to reveal internal structures hidden by the skin and bones, as well as to diagnose and treat disease. Medical imaging also establishes a database of normal anatomy and physiology to make it possible to identify abnormalities. Although imaging of removed organs and tissues can be performed for medical reasons, such procedures are usually considered part of pathology instead of medical imaging.

| Medical imaging | |

|---|---|

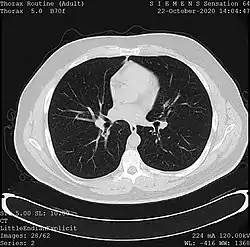

One frame of a CT scan of the chest showing the heart and lungs. | |

| ICD-10-PCS | B |

| ICD-9 | 87-88 |

| MeSH | 003952 D 003952 |

| OPS-301 code | 3 |

| MedlinePlus | 007451 |

Measurement and recording techniques that are not primarily designed to produce images, such as electroencephalography (EEG), magnetoencephalography (MEG), electrocardiography (ECG), and others, represent other technologies that produce data susceptible to representation as a parameter graph versus time or maps that contain data about the measurement locations. In a limited comparison, these technologies can be considered forms of medical imaging in another discipline.

As of 2010, 5 billion medical imaging studies had been conducted worldwide.[1] Radiation exposure from medical imaging in 2006 made up about 50% of total ionizing radiation exposure in the United States.[2] Medical imaging equipment is manufactured using technology from the semiconductor industry, including CMOS integrated circuit chips, power semiconductor devices, sensors such as image sensors (particularly CMOS sensors) and biosensors, and processors such as microcontrollers, microprocessors, digital signal processors, media processors and system-on-chip devices. As of 2015, annual shipments of medical imaging chips amount to 46 million units and $1.1 billion.[3]

Medical imaging is often perceived to designate the set of techniques that noninvasively produce images of the internal aspect of the body. In this restricted sense, medical imaging can be seen as the solution of mathematical inverse problems. This means that cause (the properties of living tissue) is inferred from effect (the observed signal). In the case of medical ultrasound, the probe consists of ultrasonic pressure waves and echoes that go inside the tissue to show the internal structure. In the case of projectional radiography, the probe uses X-ray radiation, which is absorbed at different rates by different tissue types such as bone, muscle, and fat.

The term "noninvasive" is used to denote a procedure where no instrument is introduced into a patient's body, which is the case for most imaging techniques used.

Types

In the clinical context, "invisible light" medical imaging is generally equated to radiology or "clinical imaging". "Visible light" medical imaging involves digital video or still pictures that can be seen without special equipment. Dermatology and wound care are two modalities that use visible light imagery. Interpretation of medical images is generally undertaken by a physician specialising in radiology known as a radiologist; however, this may be undertaken by any healthcare professional who is trained and certified in radiological clinical evaluation. Increasingly interpretation is being undertaken by non-physicians, for example radiographers frequently train in interpretation as part of expanded practice. Diagnostic radiography designates the technical aspects of medical imaging and in particular the acquisition of medical images. The radiographer (also known as a radiologic technologist) is usually responsible for acquiring medical images of diagnostic quality; although other professionals may train in this area, notably some radiological interventions performed by radiologists are done so without a radiographer.

As a field of scientific investigation, medical imaging constitutes a sub-discipline of biomedical engineering, medical physics or medicine depending on the context: Research and development in the area of instrumentation, image acquisition (e.g., radiography), modeling and quantification are usually the preserve of biomedical engineering, medical physics, and computer science; Research into the application and interpretation of medical images is usually the preserve of radiology and the medical sub-discipline relevant to medical condition or area of medical science (neuroscience, cardiology, psychiatry, psychology, etc.) under investigation. Many of the techniques developed for medical imaging also have scientific and industrial applications.[4]

Radiography

Two forms of radiographic images are in use in medical imaging. Projection radiography and fluoroscopy, with the latter being useful for catheter guidance. These 2D techniques are still in wide use despite the advance of 3D tomography due to the low cost, high resolution, and depending on the application, lower radiation dosages with 2D technique. This imaging modality utilizes a wide beam of x rays for image acquisition and is the first imaging technique available in modern medicine.

- Fluoroscopy produces real-time images of internal structures of the body in a similar fashion to radiography, but employs a constant input of x-rays, at a lower dose rate. Contrast media, such as barium, iodine, and air are used to visualize internal organs as they work. Fluoroscopy is also used in image-guided procedures when constant feedback during a procedure is required. An image receptor is required to convert the radiation into an image after it has passed through the area of interest. Early on this was a fluorescing screen, which gave way to an Image Amplifier (IA) which was a large vacuum tube that had the receiving end coated with cesium iodide, and a mirror at the opposite end. Eventually the mirror was replaced with a TV camera.

- Projectional radiographs, more commonly known as x-rays, are often used to determine the type and extent of a fracture as well as for detecting pathological changes in the lungs. With the use of radio-opaque contrast media, such as barium, they can also be used to visualize the structure of the stomach and intestines – this can help diagnose ulcers or certain types of colon cancer.

Magnetic resonance imaging

A magnetic resonance imaging instrument (MRI scanner), or "nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) imaging" scanner as it was originally known, uses powerful magnets to polarize and excite hydrogen nuclei (i.e., single protons) of water molecules in human tissue, producing a detectable signal which is spatially encoded, resulting in images of the body.[5] The MRI machine emits a radio frequency (RF) pulse at the resonant frequency of the hydrogen atoms on water molecules. Radio frequency antennas ("RF coils") send the pulse to the area of the body to be examined. The RF pulse is absorbed by protons, causing their direction with respect to the primary magnetic field to change. When the RF pulse is turned off, the protons "relax" back to alignment with the primary magnet and emit radio-waves in the process. This radio-frequency emission from the hydrogen-atoms on water is what is detected and reconstructed into an image. The resonant frequency of a spinning magnetic dipole (of which protons are one example) is called the Larmor frequency and is determined by the strength of the main magnetic field and the chemical environment of the nuclei of interest. MRI uses three electromagnetic fields: a very strong (typically 1.5 to 3 teslas) static magnetic field to polarize the hydrogen nuclei, called the primary field; gradient fields that can be modified to vary in space and time (on the order of 1 kHz) for spatial encoding, often simply called gradients; and a spatially homogeneous radio-frequency (RF) field for manipulation of the hydrogen nuclei to produce measurable signals, collected through an RF antenna.

Like CT, MRI traditionally creates a two-dimensional image of a thin "slice" of the body and is therefore considered a tomographic imaging technique. Modern MRI instruments are capable of producing images in the form of 3D blocks, which may be considered a generalization of the single-slice, tomographic, concept. Unlike CT, MRI does not involve the use of ionizing radiation and is therefore not associated with the same health hazards. For example, because MRI has only been in use since the early 1980s, there are no known long-term effects of exposure to strong static fields (this is the subject of some debate; see 'Safety' in MRI) and therefore there is no limit to the number of scans to which an individual can be subjected, in contrast with X-ray and CT. However, there are well-identified health risks associated with tissue heating from exposure to the RF field and the presence of implanted devices in the body, such as pacemakers. These risks are strictly controlled as part of the design of the instrument and the scanning protocols used.

Because CT and MRI are sensitive to different tissue properties, the appearances of the images obtained with the two techniques differ markedly. In CT, X-rays must be blocked by some form of dense tissue to create an image, so the image quality when looking at soft tissues will be poor. In MRI, while any nucleus with a net nuclear spin can be used, the proton of the hydrogen atom remains the most widely used, especially in the clinical setting, because it is so ubiquitous and returns a large signal. This nucleus, present in water molecules, allows the excellent soft-tissue contrast achievable with MRI.

A number of different pulse sequences can be used for specific MRI diagnostic imaging (multiparametric MRI or mpMRI). It is possible to differentiate tissue characteristics by combining two or more of the following imaging sequences, depending on the information being sought: T1-weighted (T1-MRI), T2-weighted (T2-MRI), diffusion weighted imaging (DWI-MRI), dynamic contrast enhancement (DCE-MRI), and spectroscopy (MRI-S). For example, imaging of prostate tumors is better accomplished using T2-MRI and DWI-MRI than T2-weighted imaging alone.[6] The number of applications of mpMRI for detecting disease in various organs continues to expand, including liver studies, breast tumors, pancreatic tumors, and assessing the effects of vascular disruption agents on cancer tumors.[7][8][9]

Nuclear medicine

Nuclear medicine encompasses both diagnostic imaging and treatment of disease, and may also be referred to as molecular medicine or molecular imaging and therapeutics.[10] Nuclear medicine uses certain properties of isotopes and the energetic particles emitted from radioactive material to diagnose or treat various pathology. Different from the typical concept of anatomic radiology, nuclear medicine enables assessment of physiology. This function-based approach to medical evaluation has useful applications in most subspecialties, notably oncology, neurology, and cardiology. Gamma cameras and PET scanners are used in e.g. scintigraphy, SPECT and PET to detect regions of biologic activity that may be associated with a disease. Relatively short-lived isotope, such as 99mTc is administered to the patient. Isotopes are often preferentially absorbed by biologically active tissue in the body, and can be used to identify tumors or fracture points in bone. Images are acquired after collimated photons are detected by a crystal that gives off a light signal, which is in turn amplified and converted into count data.

- Scintigraphy ("scint") is a form of diagnostic test wherein radioisotopes are taken internally, for example, intravenously or orally. Then, gamma cameras capture and form two-dimensional[11] images from the radiation emitted by the radiopharmaceuticals.

- SPECT is a 3D tomographic technique that uses gamma camera data from many projections and can be reconstructed in different planes. A dual detector head gamma camera combined with a CT scanner, which provides localization of functional SPECT data, is termed a SPECT-CT camera, and has shown utility in advancing the field of molecular imaging. In most other medical imaging modalities, energy is passed through the body and the reaction or result is read by detectors. In SPECT imaging, the patient is injected with a radioisotope, most commonly Thallium 201TI, Technetium 99mTC, Iodine 123I, and Gallium 67Ga.[12] The radioactive gamma rays are emitted through the body as the natural decaying process of these isotopes takes place. The emissions of the gamma rays are captured by detectors that surround the body. This essentially means that the human is now the source of the radioactivity, rather than the medical imaging devices such as X-ray or CT.

- Positron emission tomography (PET) uses coincidence detection to image functional processes. Short-lived positron emitting isotope, such as 18F, is incorporated with an organic substance such as glucose, creating F18-fluorodeoxyglucose, which can be used as a marker of metabolic utilization. Images of activity distribution throughout the body can show rapidly growing tissue, like tumor, metastasis, or infection. PET images can be viewed in comparison to computed tomography scans to determine an anatomic correlate. Modern scanners may integrate PET, allowing PET-CT, or PET-MRI to optimize the image reconstruction involved with positron imaging. This is performed on the same equipment without physically moving the patient off of the gantry. The resultant hybrid of functional and anatomic imaging information is a useful tool in non-invasive diagnosis and patient management.

Fiduciary markers are used in a wide range of medical imaging applications. Images of the same subject produced with two different imaging systems may be correlated (called image registration) by placing a fiduciary marker in the area imaged by both systems. In this case, a marker which is visible in the images produced by both imaging modalities must be used. By this method, functional information from SPECT or positron emission tomography can be related to anatomical information provided by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).[13] Similarly, fiducial points established during MRI can be correlated with brain images generated by magnetoencephalography to localize the source of brain activity.

Ultrasound

Medical ultrasound uses high frequency broadband sound waves in the megahertz range that are reflected by tissue to varying degrees to produce (up to 3D) images. This is commonly associated with imaging the fetus in pregnant women. Uses of ultrasound are much broader, however. Other important uses include imaging the abdominal organs, heart, breast, muscles, tendons, arteries and veins. While it may provide less anatomical detail than techniques such as CT or MRI, it has several advantages which make it ideal in numerous situations, in particular that it studies the function of moving structures in real-time, emits no ionizing radiation, and contains speckle that can be used in elastography. Ultrasound is also used as a popular research tool for capturing raw data, that can be made available through an ultrasound research interface, for the purpose of tissue characterization and implementation of new image processing techniques. The concepts of ultrasound differ from other medical imaging modalities in the fact that it is operated by the transmission and receipt of sound waves. The high frequency sound waves are sent into the tissue and depending on the composition of the different tissues; the signal will be attenuated and returned at separate intervals. A path of reflected sound waves in a multilayered structure can be defined by an input acoustic impedance (ultrasound sound wave) and the Reflection and transmission coefficients of the relative structures.[12] It is very safe to use and does not appear to cause any adverse effects. It is also relatively inexpensive and quick to perform. Ultrasound scanners can be taken to critically ill patients in intensive care units, avoiding the danger caused while moving the patient to the radiology department. The real-time moving image obtained can be used to guide drainage and biopsy procedures. Doppler capabilities on modern scanners allow the blood flow in arteries and veins to be assessed.

Elastography

Elastography is a relatively new imaging modality that maps the elastic properties of soft tissue. This modality emerged in the last two decades. Elastography is useful in medical diagnoses, as elasticity can discern healthy from unhealthy tissue for specific organs/growths. For example, cancerous tumours will often be harder than the surrounding tissue, and diseased livers are stiffer than healthy ones.[14][15][16][17] There are several elastographic techniques based on the use of ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging and tactile imaging. The wide clinical use of ultrasound elastography is a result of the implementation of technology in clinical ultrasound machines. Main branches of ultrasound elastography include Quasistatic Elastography/Strain Imaging, Shear Wave Elasticity Imaging (SWEI), Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse imaging (ARFI), Supersonic Shear Imaging (SSI), and Transient Elastography.[15] In the last decade a steady increase of activities in the field of elastography is observed demonstrating successful application of the technology in various areas of medical diagnostics and treatment monitoring.

Photoacoustic imaging

Photoacoustic imaging is a recently developed hybrid biomedical imaging modality based on the photoacoustic effect. It combines the advantages of optical absorption contrast with an ultrasonic spatial resolution for deep imaging in (optical) diffusive or quasi-diffusive regime. Recent studies have shown that photoacoustic imaging can be used in vivo for tumor angiogenesis monitoring, blood oxygenation mapping, functional brain imaging, and skin melanoma detection, etc.

Tomography

Tomography is the imaging by sections or sectioning. The main such methods in medical imaging are:

- X-ray computed tomography (CT), or Computed Axial Tomography (CAT) scan, is a helical tomography technique (latest generation), which traditionally produces a 2D image of the structures in a thin section of the body. In CT, a beam of X-rays spins around an object being examined and is picked up by sensitive radiation detectors after having penetrated the object from multiple angles. A computer then analyses the information received from the scanner's detectors and constructs a detailed image of the object and its contents using the mathematical principles laid out in the Radon transform. It has a greater ionizing radiation dose burden than projection radiography; repeated scans must be limited to avoid health effects. CT is based on the same principles as X-Ray projections but in this case, the patient is enclosed in a surrounding ring of detectors assigned with 500–1000 scintillation detectors[12] (fourth-generation X-Ray CT scanner geometry). Previously in older generation scanners, the X-Ray beam was paired by a translating source and detector. Computed tomography has almost completely replaced focal plane tomography in X-ray tomography imaging.

- Positron emission tomography (PET) also used in conjunction with computed tomography, PET-CT, and magnetic resonance imaging PET-MRI.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) commonly produces tomographic images of cross-sections of the body. (See separate MRI section in this article.)

Echocardiography

When ultrasound is used to image the heart it is referred to as an echocardiogram. Echocardiography allows detailed structures of the heart, including chamber size, heart function, the valves of the heart, as well as the pericardium (the sac around the heart) to be seen. Echocardiography uses 2D, 3D, and Doppler imaging to create pictures of the heart and visualize the blood flowing through each of the four heart valves. Echocardiography is widely used in an array of patients ranging from those experiencing symptoms, such as shortness of breath or chest pain, to those undergoing cancer treatments. Transthoracic ultrasound has been proven to be safe for patients of all ages, from infants to the elderly, without risk of harmful side effects or radiation, differentiating it from other imaging modalities. Echocardiography is one of the most commonly used imaging modalities in the world due to its portability and use in a variety of applications. In emergency situations, echocardiography is quick, easily accessible, and able to be performed at the bedside, making it the modality of choice for many physicians.

Functional near-infrared spectroscopy

FNIR Is a relatively new non-invasive imaging technique. NIRS (near infrared spectroscopy) is used for the purpose of functional neuroimaging and has been widely accepted as a brain imaging technique.[18]

Magnetic particle imaging

Using superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles, magnetic particle imaging (MPI) is a developing diagnostic imaging technique used for tracking superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles. The primary advantage is the high sensitivity and specificity, along with the lack of signal decrease with tissue depth. MPI has been used in medical research to image cardiovascular performance, neuroperfusion, and cell tracking.

In pregnancy

.gif)

Medical imaging may be indicated in pregnancy because of pregnancy complications, a pre-existing disease or an acquired disease in pregnancy, or routine prenatal care. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) without MRI contrast agents as well as obstetric ultrasonography are not associated with any risk for the mother or the fetus, and are the imaging techniques of choice for pregnant women.[19] Projectional radiography, CT scan and nuclear medicine imaging result some degree of ionizing radiation exposure, but have with a few exceptions much lower absorbed doses than what are associated with fetal harm.[19] At higher dosages, effects can include miscarriage, birth defects and intellectual disability.[19]

Maximizing imaging procedure use

The amount of data obtained in a single MR or CT scan is very extensive. Some of the data that radiologists discard could save patients time and money, while reducing their exposure to radiation and risk of complications from invasive procedures.[20] Another approach for making the procedures more efficient is based on utilizing additional constraints, e.g., in some medical imaging modalities one can improve the efficiency of the data acquisition by taking into account the fact the reconstructed density is positive.[21][22]

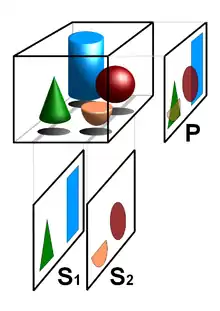

Creation of three-dimensional images

Volume rendering techniques have been developed to enable CT, MRI and ultrasound scanning software to produce 3D images for the physician.[23] Traditionally CT and MRI scans produced 2D static output on film. To produce 3D images, many scans are made and then combined by computers to produce a 3D model, which can then be manipulated by the physician. 3D ultrasounds are produced using a somewhat similar technique. In diagnosing disease of the viscera of the abdomen, ultrasound is particularly sensitive on imaging of biliary tract, urinary tract and female reproductive organs (ovary, fallopian tubes). As for example, diagnosis of gallstone by dilatation of common bile duct and stone in the common bile duct. With the ability to visualize important structures in great detail, 3D visualization methods are a valuable resource for the diagnosis and surgical treatment of many pathologies. It was a key resource for the famous, but ultimately unsuccessful attempt by Singaporean surgeons to separate Iranian twins Ladan and Laleh Bijani in 2003. The 3D equipment was used previously for similar operations with great success.

Other proposed or developed techniques include:

- Diffuse optical tomography

- Elastography

- Electrical impedance tomography

- Optoacoustic imaging

- Ophthalmology

Some of these techniques are still at a research stage and not yet used in clinical routines.

Non-diagnostic imaging

Neuroimaging has also been used in experimental circumstances to allow people (especially disabled persons) to control outside devices, acting as a brain computer interface.

Many medical imaging software applications are used for non-diagnostic imaging, specifically because they don't have an FDA approval[24] and not allowed to use in clinical research for patient diagnosis.[25] Note that many clinical research studies are not designed for patient diagnosis anyway.[26]

Archiving and recording

Used primarily in ultrasound imaging, capturing the image produced by a medical imaging device is required for archiving and telemedicine applications. In most scenarios, a frame grabber is used in order to capture the video signal from the medical device and relay it to a computer for further processing and operations.[27]

DICOM

The Digital Imaging and Communication in Medicine (DICOM) Standard is used globally to store, exchange, and transmit medical images. The DICOM Standard incorporates protocols for imaging techniques such as radiography, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), ultrasound, and radiation therapy.[28]

Compression of medical images

Medical imaging techniques produce very large amounts of data, especially from CT, MRI and PET modalities. As a result, storage and communications of electronic image data are prohibitive without the use of compression.[29][30] JPEG 2000 image compression is used by the DICOM standard for storage and transmission of medical images. The cost and feasibility of accessing large image data sets over low or various bandwidths are further addressed by use of another DICOM standard, called JPIP, to enable efficient streaming of the JPEG 2000 compressed image data.

Medical imaging in the cloud

There has been growing trend to migrate from on-premise PACS to a cloud-based PACS. A recent article by Applied Radiology said, "As the digital-imaging realm is embraced across the healthcare enterprise, the swift transition from terabytes to petabytes of data has put radiology on the brink of information overload. Cloud computing offers the imaging department of the future the tools to manage data much more intelligently."[31]

Use in pharmaceutical clinical trials

Medical imaging has become a major tool in clinical trials since it enables rapid diagnosis with visualization and quantitative assessment.

A typical clinical trial goes through multiple phases and can take up to eight years. Clinical endpoints or outcomes are used to determine whether the therapy is safe and effective. Once a patient reaches the endpoint, he or she is generally excluded from further experimental interaction. Trials that rely solely on clinical endpoints are very costly as they have long durations and tend to need large numbers of patients.

In contrast to clinical endpoints, surrogate endpoints have been shown to cut down the time required to confirm whether a drug has clinical benefits. Imaging biomarkers (a characteristic that is objectively measured by an imaging technique, which is used as an indicator of pharmacological response to a therapy) and surrogate endpoints have shown to facilitate the use of small group sizes, obtaining quick results with good statistical power.[32]

Imaging is able to reveal subtle change that is indicative of the progression of therapy that may be missed out by more subjective, traditional approaches. Statistical bias is reduced as the findings are evaluated without any direct patient contact.

Imaging techniques such as positron emission tomography (PET) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are routinely used in oncology and neuroscience areas,.[33][34][35][36] For example, measurement of tumour shrinkage is a commonly used surrogate endpoint in solid tumour response evaluation. This allows for faster and more objective assessment of the effects of anticancer drugs. In Alzheimer's disease, MRI scans of the entire brain can accurately assess the rate of hippocampal atrophy,[37][38] while PET scans can measure the brain's metabolic activity by measuring regional glucose metabolism,[32] and beta-amyloid plaques using tracers such as Pittsburgh compound B (PiB). Historically less use has been made of quantitative medical imaging in other areas of drug development although interest is growing.[39]

An imaging-based trial will usually be made up of three components:

- A realistic imaging protocol. The protocol is an outline that standardizes (as far as practically possible) the way in which the images are acquired using the various modalities (PET, SPECT, CT, MRI). It covers the specifics in which images are to be stored, processed and evaluated.

- An imaging centre that is responsible for collecting the images, perform quality control and provide tools for data storage, distribution and analysis. It is important for images acquired at different time points are displayed in a standardised format to maintain the reliability of the evaluation. Certain specialised imaging contract research organizations provide end to end medical imaging services, from protocol design and site management through to data quality assurance and image analysis.

- Clinical sites that recruit patients to generate the images to send back to the imaging centre.

Shielding

Lead is the main material used for radiographic shielding against scattered X-rays.

In magnetic resonance imaging, there is MRI RF shielding as well as magnetic shielding to prevent external disturbance of image quality.[40]

Privacy protection

Medical imaging are generally covered by laws of medical privacy. For example, in the United States the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) sets restrictions for health care providers on utilizing protected health information, which is any individually identifiable information relating to the past, present, or future physical or mental health of any individual.[41] While there has not been any definitive legal decision in the matter, at least one study has indicated that medical imaging may contain biometric information that can uniquely identify a person, and so may qualify as PHI.[42]

The UK General Medical Council's ethical guidelines indicate that the Council does not require consent prior to secondary uses of X-ray images.[43]

Industry

Organizations in the medical imaging industry include manufacturers of imaging equipment, freestanding radiology facilities, and hospitals.

The global market for manufactured devices was estimated at $5 billion in 2018.[44] Notable manufacturers as of 2012 included Fujifilm, GE, Siemens Healthineers, Philips, Shimadzu, Toshiba, Carestream Health, Hitachi, Hologic, and Esaote.[45] In 2016, the manufacturing industry was characterized as oligopolistic and mature; new entrants included in Samsung and Neusoft Medical.[46]

In the United States, as estimate as of 2015 places the US market for imaging scans at about $100b, with 60% occurring in hospitals and 40% occurring in freestanding clinics, such as the RadNet chain.[47]

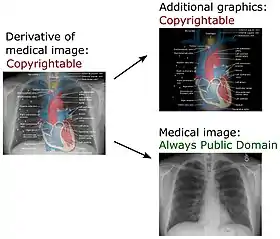

Copyright

United States

As per chapter 300 of the Compendium of U.S. Copyright Office Practices, "the Office will not register works produced by a machine or mere mechanical process that operates randomly or automatically without any creative input or intervention from a human author" including "Medical imaging produced by x-rays, ultrasounds, magnetic resonance imaging, or other diagnostic equipment."[48] This position differs from the broad copyright protections afforded to photographs. While the Copyright Compendium is an agency statutory interpretation and not legally binding, courts are likely to give deference to it if they find it reasonable.[49] Yet, there is no U.S. federal case law directly addressing the issue of the copyrightability of x-ray images.

Derivatives

An extensive definition of the term derivative work is given by the United States Copyright Act in 17 U.S.C. § 101:

A "derivative work" is a work based upon one or more preexisting works, such as a translation...[note 1] art reproduction, abridgment, condensation, or any other form in which a work may be recast, transformed, or adapted. A work consisting of editorial revisions, annotations, elaborations, or other modifications which, as a whole, represent an original work of authorship, is a "derivative work".

17 U.S.C. § 103(b) provides:

The copyright in a compilation or derivative work extends only to the material contributed by the author of such work, as distinguished from the preexisting material employed in the work, and does not imply any exclusive right in the preexisting material. The copyright in such work is independent of, and does not affect or enlarge the scope, duration, ownership, or subsistence of, any copyright protection in the preexisting material.

Germany

In Germany, X-ray images as well as MRI, medical ultrasound, PET and scintigraphy images are protected by (copyright-like) related rights or neighbouring rights.[50] This protection does not require creativity (as would be necessary for regular copyright protection) and lasts only for 50 years after image creation, if not published within 50 years, or for 50 years after the first legitimate publication.[51] The letter of the law grants this right to the "Lichtbildner",[52] i.e. the person who created the image. The literature seems to uniformly consider the medical doctor, dentist or veterinary physician as the rights holder, which may result from the circumstance that in Germany many x-rays are performed in ambulatory settings.

United Kingdom

Medical images created in the United Kingdom will normally be protected by copyright due to "the high level of skill, labour and judgement required to produce a good quality x-ray, particularly to show contrast between bones and various soft tissues".[53] The Society of Radiographers believe this copyright is owned by employer (unless the radiographer is self-employed—though even then their contract might require them to transfer ownership to the hospital). This copyright owner can grant certain permissions to whoever they wish, without giving up their ownership of the copyright. So the hospital and its employees will be given permission to use such radiographic images for the various purposes that they require for medical care. Physicians employed at the hospital will, in their contracts, be given the right to publish patient information in journal papers or books they write (providing they are made anonymous). Patients may also be granted permission to "do what they like with" their own images.

Sweden

The Cyber Law in Sweden states: "Pictures can be protected as photographic works or as photographic pictures. The former requires a higher level of originality; the latter protects all types of photographs, also the ones taken by amateurs, or within medicine or science. The protection requires some sort of photographic technique being used, which includes digital cameras as well as holograms created by laser technique. The difference between the two types of work is the term of protection, which amounts to seventy years after the death of the author of a photographic work as opposed to fifty years, from the year in which the photographic picture was taken."[54]

Medical imaging may possibly be included in the scope of "photography", similarly to a U.S. statement that "MRI images, CT scans, and the like are analogous to photography."[55]

See also

- Medical image sharing

- Imaging instruments

Explanatory notes

- musical arrangement, dramatization, fictionalization, motion picture version, sound recording

References

- Roobottom CA, Mitchell G, Morgan-Hughes G (November 2010). "Radiation-reduction strategies in cardiac computed tomographic angiography". Clinical Radiology. 65 (11): 859–67. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2010.04.021. PMID 20933639.

- "Medical Radiation Exposure Of The U.S. Population Greatly Increased Since The Early 1980s" (Press release). National Council on Radiation Protection & Measurements. March 5, 2009. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- "Medical Imaging Chip Global Unit Volume To Soar Over the Next Five Years". Silicon Semiconductor. 8 September 2016. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- James AP, Dasarathy BV (2014). "Medical Image Fusion: A survey of state of the art". Information Fusion. 19: 4–19. arXiv:1401.0166. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2013.12.002. S2CID 15315731.

- Brown RW, Cheng YN, Haacke EM, Thompson MR, Venkatesan R (2 May 2014). Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Physical Principles and Sequence Design. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-118-63397-7.

- Sperling, MD, D. "Combining MRI parameters is better than T2 weighting alone". sperlingprostatecenter.com. Sperling Prostate Center. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- Banerjee R, Pavlides M, Tunnicliffe EM, Piechnik SK, Sarania N, Philips R, Collier JD, Booth JC, Schneider JE, Wang LM, Delaney DW, Fleming KA, Robson MD, Barnes E, Neubauer S (January 2014). "Multiparametric magnetic resonance for the non-invasive diagnosis of liver disease". Journal of Hepatology. 60 (1): 69–77. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2013.09.002. PMC 3865797. PMID 24036007.

- Rahbar H, Partridge SC (February 2016). "Multiparametric MR Imaging of Breast Cancer". Magnetic Resonance Imaging Clinics of North America. 24 (1): 223–238. doi:10.1016/j.mric.2015.08.012. PMC 4672390. PMID 26613883.

- Scialpi M, Reginelli A, D'Andrea A, Gravante S, Falcone G, Baccari P, Manganaro L, Palumbo B, Cappabianca S (April 2016). "Pancreatic tumors imaging: An update" (PDF). International Journal of Surgery. 28 Suppl 1: S142-55. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.12.053. PMID 26777740.

- "Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (SNMMI)". Snm.org. Archived from the original on 2013-08-14. Retrieved 2013-08-16.

- "scintigraphy – definition of scintigraphy in the Medical dictionary". Medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com. Retrieved 2013-08-16.

- Dhawan, Atam P. (2003). Medical Image Analysis. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 978-0-471-45131-0.

- Erickson BJ, Jack CR (May 1993). "Correlation of single photon emission CT with MR image data using fiduciary markers". AJNR. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 14 (3): 713–20. PMC 8333382. PMID 8517364.

- Wells PN, Liang HD (November 2011). "Medical ultrasound: imaging of soft tissue strain and elasticity". Journal of the Royal Society, Interface. 8 (64): 1521–49. doi:10.1098/rsif.2011.0054. PMC 3177611. PMID 21680780.

- Sarvazyan A, Hall TJ, Urban MW, Fatemi M, Aglyamov SR, Garra BS (November 2011). "Overview of elastography–an emerging branch of medical imaging". Current Medical Imaging Reviews. 7 (4): 255–282. doi:10.2174/157340511798038684. PMC 3269947. PMID 22308105.

- Ophir J, Céspedes I, Ponnekanti H, Yazdi Y, Li X (April 1991). "Elastography: a quantitative method for imaging the elasticity of biological tissues". Ultrasonic Imaging. 13 (2): 111–34. doi:10.1016/0161-7346(91)90079-W. PMID 1858217.

- Parker KJ, Doyley MM, Rubens DJ (2011). "Imaging the elastic properties of tissue: the 20 year perspective". Physics in Medicine and Biology. 56 (2): R1–R29. Bibcode:2012PMB....57.5359P. doi:10.1088/0031-9155/57/16/5359. PMID 21119234.

- Villringer A, Chance B (October 1997). "Non-invasive optical spectroscopy and imaging of human brain function". Trends in Neurosciences. 20 (10): 435–42. doi:10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01132-6. PMID 9347608. S2CID 18077839.

- "Guidelines for Diagnostic Imaging During Pregnancy and Lactation". American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. February 2016

- Freiherr G. Waste not, want not: Getting the most from imaging procedures. Diagnostic Imaging. March 19, 2010.

- Nemirovsky J, Shimron E (2015). "Utilizing Bochners Theorem for Constrained Evaluation of Missing Fourier Data". arXiv:1506.03300 [physics.med-ph].

- Perera Molligoda Arachchige, Arosh S.; Svet, Afanasy (2021-09-10). "Integrating artificial intelligence into radiology practice: undergraduate students' perspective". European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 48 (13): 4133–4135. doi:10.1007/s00259-021-05558-y. ISSN 1619-7089. PMID 34505175. S2CID 237459138.

- Udupa JK, Herman GT (2000). 3D Imaging in Medicine (2nd ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 9780849331794.

- FDA: Device Approvals and Clearances, . Retrieved 2012-31-08

- "FDA: Statistical Guidance for Clinical Trials of Non Diagnostic Medical Devices". Fda.gov. Retrieved August 31, 2012.

- Kolata, Gina (August 25, 2012). "Genes Now Tell Doctors Secrets They Can't Utter". The New York Times. Retrieved August 31, 2012.

- "Treating Medical Ailments in Real Time Using Epiphan DVI2USB | Solutions | Epiphan Systems". Epiphan.com. Retrieved 2013-08-16.

- Kahn CE, Carrino JA, Flynn MJ, Peck DJ, Horii SC (September 2007). "DICOM and radiology: past, present, and future". Journal of the American College of Radiology. 4 (9): 652–7. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2007.06.004. PMID 17845973.

- Nagornov, Nikolay N.; Lyakhov, Pavel A.; Valueva, Maria V.; Bergerman, Maxim V. (2022). "RNS-Based FPGA Accelerators for High-Quality 3D Medical Image Wavelet Processing Using Scaled Filter Coefficients". IEEE Access. 10: 19215–19231. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3151361. ISSN 2169-3536. S2CID 246895876.

Medical imaging systems produce increasingly accurate images with improved quality using higher spatial resolutions and color bit-depth. Such improvements increase the amount of information that needs to be stored, processed, and transmitted.

- Dhouib, D.; Naït-Ali, A.; Olivier, C.; Naceur, M.S. (June 2021). "ROI-Based Compression Strategy of 3D MRI Brain Datasets for Wireless Communications". IRBM. 42 (3): 146–153. doi:10.1016/j.irbm.2020.05.001. S2CID 219437400.

Because of the large amount of medical imaging data, the transmission process becomes complicated in telemedicine applications. Thus, in order to adapt the data bit streams to the constraints related to the limitation of the bandwidths a reduction of the size of the data by compression of the images is essential.

- Shrestha RB (May 2011). "Imaging on the cloud" (PDF). Applied Radiology. 40 (5): 8–12. doi:10.37549/AR1820. S2CID 247970009.

- Hajnal JV, Hill DL (June 2001). Medical image registration. CRC press. ISBN 978-1-4200-4247-4.

- Hargreaves RJ (February 2008). "The role of molecular imaging in drug discovery and development". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 83 (2): 349–53. doi:10.1038/sj.clpt.6100467. PMID 18167503. S2CID 35516906.

- Willmann JK, van Bruggen N, Dinkelborg LM, Gambhir SS (July 2008). "Molecular imaging in drug development". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 7 (7): 591–607. doi:10.1038/nrd2290. PMID 18591980. S2CID 37571813.

- McCarthy TJ (August 2009). "The role of imaging in drug development". The Quarterly Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 53 (4): 382–6. PMID 19834447.

- Matthews PM, Rabiner I, Gunn R (October 2011). "Non-invasive imaging in experimental medicine for drug development". Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 11 (5): 501–7. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2011.04.009. PMID 21570913.

- Sadek, Rowayda A. (May 2012). "An improved MRI segmentation for atrophy assessment". International Journal of Computer Science Issues (IJCSI). 9 (3): 569–74. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.402.1227.

- Rowayda, A. Sadek (February 2013). "Regional atrophy analysis of MRI for early detection of alzheimer's disease". International Journal of Signal Processing, Image Processing and Pattern Recognition. 6 (1): 49–53.

- Comley RA, Kallend D (February 2013). "Imaging in the cardiovascular and metabolic disease area". Drug Discovery Today. 18 (3–4): 185–92. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2012.09.008. PMID 23032726.

- Winkler SA, Schmitt F, Landes H, de Bever J, Wade T, Alejski A, Rutt BK (March 2018). "Gradient and shim technologies for ultra high field MRI". NeuroImage. 168: 59–70. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.11.033. PMC 5591082. PMID 27915120.

- HIPAA 45 CFR Part 160.103 (2013). Available at https://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/administrative/combined/hipaa-simplification-201303.pdf Archived 2015-06-12 at the Wayback Machine, Accessed Sept. 17, 2014.

- Shamir L, Ling S, Rahimi S, Ferrucci L, Goldberg IG (January 2009). "Biometric identification using knee X-rays". International Journal of Biometrics. 1 (3): 365–370. doi:10.1504/IJBM.2009.024279. PMC 2748324. PMID 20046910.

- Recordings for which separate consent is not required, General Medical Council, Available at http://www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/ethical_guidance/7840.asp, Accessed October 1, 2014. None of the aforementioned sources are legally binding and court outcomes may vary.

- Kincaid, Ellie. "Want Fries With That? A Brief History Of Medical MRI, Starting With A McDonald's". Forbes. Retrieved 2019-05-25.

- "Top ten diagnostic imaging device manufacturers". Verdict Hospital. 2012-10-30. Retrieved 2019-05-25.

- "The €32 billion diagnostic imaging market at a crossroads". healthcare-in-europe.com. Retrieved 2019-05-25.

- "The Future of Imaging Diagnostic Centers in China". the Pulse. Retrieved 2019-05-25.

- Compendium of U.S. Copyright Office practices

- Craigslist Inc. v. 3Taps Inc., 942 F.Supp.2d 962, 976 (N.D. Cal. 2013) ("Interpretation of copyright law in the Compendium II is 'entitled to judicial deference if reasonable.'"). Available here; accessed Sept. 25, 2014.

- Per §72 UrhG like “simple images” (Lichtbild)

-

- Scholarly legal literature:(Schulze, in: Dreier/Schulze, 2013, §72 Rdnr. 6 w. reference to Schricker/Vogel §72 Rdnr. 18 and Wandtke/Bullinger/Thum §72 Rdnr. 10 and Thum, in: Wandtke/Bullinger, UrhG, 32009, §72, Rn. 15.)

- Legal commentaries: K. Hartung, E. Ludewig, B. Tellhelm: Röntgenuntersuchung in der Tierarztpraxis. Enke, 2010 or T. Hillegeist: Rechtliche Probleme der elektronischen Langzeitarchivierung wissenschaftlicher Primärdaten. Universitätsverlag Göttingen, 2012 or S.C. Linnemann: Veröffentlichung „anonymisierter“ Röntgenbilder. Dent Implantol 17, 2, 132-134 (2013)

- Indirectly by a ruling of a German 2nd-level court: (LG Aachen, Urteil v. 16. Oktober 1985, Az. 7 S 90/85 ), which mentions copyright in x-ray images, and by the Röntgenverordnung of Germany, a federal regulation about the protection against damages by x-rays, which in §28 Abs. 5 twice mentions the “Urheber” (author/creator) of x-ray images . Archived 2014-12-22 at the Wayback Machine

- "§ 72 UrhG - Einzelnorm".

- Michalos, Christina (2004). The law of photography and digital images. Sweet & Maxwell. ISBN 978-0-421-76470-5.

- Cyber Law in Sweden. p. 96.

- "Laser Bones: Copyright Issues Raised by the Use of Information Technology in Archaeology" (PDF). Harvard Journal of Law & Technology. 10 (2). 1997. (p. 296)

Further reading

- Cho Z, Jones JP, Singh M (1993). Foundations of medical imaging. New York: Wiley. ISBN 0-471-54573-2.

- Eisenberg RL, Margulis AR (2011). A Patient's Guide to Medical Imaging. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-972991-3.

- Udupa JK, Herman GT (1999). 3D Imaging in Medicine (Second ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-84-933179-4.