Moulage

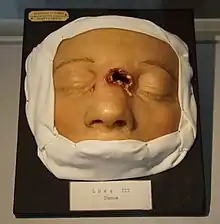

Moulage (French for 'casting, moulding') is the art of applying mock injuries for the purpose of training emergency response teams and other medical and military personnel. Moulage may be as simple as applying pre-made rubber or latex "wounds" to a healthy "patient's" limbs, chest, head, etc., or as complex as using makeup and theatre techniques to provide elements of realism (such as blood, vomitus, open fractures, etc.[1]) to the training simulation. The practice dates to at least the Renaissance, when wax figures were used for this purpose.[2]

In Germany some universities and hospitals use their historical moulage collections for the training of students. The often very lifelike models are especially useful to show the students today the characteristics of rare diseases, such as skin tuberculosis or leprosy.[3]

History

Up until the 16th century, European scientists had little knowledge about human anatomy and anatomy of animals. Medical students of Bologna and Paris studied the books of Aristotle, Galen, and other Greek scholars. Four centuries after the invasion by the Arabs and the fall of Rome and Persia, many Greek books were translated into the Arabic language. European scientists then translated these Arabic books into the Latin and Greek languages. In the medical field, this led to a reliance on Galen as a medical authority in European countries. In European medical schools the professors of anatomy merely lectured from Galen, without any dissection of the human body, and Galen’s books were the only way to learn anatomy.

.JPG.webp)

Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564), a Flemish anatomist, was at first a "Galenist" at the University of Paris. When he moved to Italy and entered the University of Padua, he began dissecting human bodies. He studied many details of human anatomy and found that Galen made some anatomical mistakes. For example, Galen wrote that the sternum has seven segments, but Vesalius found it has three segments. Galen wrote that the bone of the arm is the longest bone in the human body, but Vesalius found that the bone of the thigh is actually the longest bone in human body. At age 25 Vesalius realized that the anatomical knowledge of Galen was derived from animal anatomy and therefore Galen had never dissected a human body.

In 1543 Vesalius wrote an anatomical masterwork named in Latin De humani corporis fabrica libri septem ("On the fabric of the human body in seven books"), or in short De Fabrica. The book included drawings of human females and males with their skins dissected.[4] These pictures greatly influenced the creation of future anatomical wax models. The anatomical pictures of Vesalius were followed by those of Johann Vesling ("Veslingius") and Hieronymus Fabricius. By 1600 Fabricius had gathered 300 anatomical paintings and made an anatomical atlas named the Tabulae Pictae. Giulio Cesare Casseri ("Casserius"), Spighelius, and William Harvey are other followers of the pictures of Andreas Vesalius.

The Tabulae anatomicae of Bartolomeo Eustachi ("Eustachius") (1552), printed in 1714, had a major effect on the history of anatomical wax models. This work so affected Pope Benedict XIV that he ordered construction of a museum of anatomy in Bologna In 1742, named Ercole Lelli and featuring anatomical wax models. Felice Fontana made cadaveric specimens into wax models by the casting method for anatomical teaching.[5]

The history of wax models is ancient. Wax anatomical models were first made by Gaetano Giulio Zummo (1656–1701) who first worked in Naples, then Florence, and finally Paris, where he was granted monopoly right by Louis XIV. Later, Jules Baretta (1834–1923) made more than 2000 wax models in Hospital Saint-Louis, Paris, where more than 4000 wax models were collected. While wax models were being made, he made pleasant conversations with the patients, sang songs or at times played the piano. Moulages were made for the education of dermatologists around the world, but were eventually replaced by color slides.

Wax sculpture, use in moulage

The modeling of the soft parts of dissections, teaching illustrations of anatomy, was first practiced at Florence during the Renaissance. The practice of moulage, or the depiction of human anatomy and different diseases taken from directly casting from the body using (in the early period) gelatine moulds, later alginate or silicone moulds, used wax as its primary material (later to be replaced by latex and rubber). Some moulages were directly cast from the bodies of diseased subjects, others from healthy subjects to which disease features (blisters, sores, growths, rashes) were skilfully applied with wax and pigments. During the 19th century, moulage evolved into three-dimensional, realistic representations of diseased parts of the human body. These can be seen in many European medical museums, notably the Spitzner collection currently in Brussels, the Charite Hospital museum in Berlin and the Gordon Museum of Pathology at Guy's Hospital in London UK.

A comprehensive book monograph on moulages is "Diseases in Wax: the History of Medical Moulage" by Thomas Schnalke (Author) the director of the Charite Museum and Kathy Spatschek (Translator). In the 19th century moulage was taken of medical patients for educational purposes. The prepared model was painted to mimic the original disease. Nowadays anatomicals model are an important instrument of education of human anatomy in department of anatomy and biological sciences in medical schools.[6]

Modern moulage

Moulage has evolved dramatically since its original intent. In modern terms, the word moulage refers to the use of "special effects makeup (SPFX) and casting or moulding techniques that replicate illnesses or wounds"[7] in simulation based techniques. Common examples include designing diabetic wounds, creating burns or other illness effects, like dermatological rashes[8][9] and gunshot wounds.[10]

These illness and injury effects are applied to training manikins or simulated or standardized patients for training or other purposes. Simulation staff attend training to learn these techniques. It is argued that the use of moulage in simulation improves realism or participant buy-in.[8] Moulage is an emerging field of research for paramedicine, radiography and medical education,[11][12][13] with researchers exploring how moulage contributes to learning in training. Military training utilises highly-authentic moulage techniques to desensitise to graphic wounds, prepare for battle, and treat injuries.[14] New advancements in the field include using tattooed injuries and moulage through augmented reality.[15] The level of authenticity required for moulage remains unclear.[7]

See also

- Makeup

- EMS

- Objective Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCE)

- Theatrical blood

References

- http://casemed.case.edu/simcenter/resources/moulage.cfm Moulage

- "UNMC History 101: Medicine in wax". University of Nebraska Medical Center. January 7, 2014.

- "UKE - Klinik und Poliklinik für Dermatologie und Venerologie - Moulagen, Moulagensammlung, UKE, Universitätsklinikum Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Hautklinik". Archived from the original on 2014-01-05. Retrieved 2014-01-04.

- http://evolution.berkeley.edu/evolibrary/article/history_02Comparative Anatomy: Andreas Vesalius

- Alessandro Riva, Gabriele Conti, Paola Solinas and Francesco Loy .The evolution of anatomical illustration and wax modelling in Italy from the 16th to early 19th centuries. J. Anat. (2010) 216, pp209–222, doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2009.01157.x

- Wax sculpture#Use in moulage

- Stokes-Parish, Jessica; Duvivier, Robbert; Jolly, Brian (2019-07-08). "Expert opinions on the authenticity of moulage in simulation: a Delphi study". Advances in Simulation. 4 (1): 16. doi:10.1186/s41077-019-0103-z. ISSN 2059-0628. PMC 6615296. PMID 31333880.

- Stokes-Parish, Jessica B.; Duvivier, Robbert; Jolly, Brian (December 2016). "Does Appearance Matter? Current Issues and Formulation of a Research Agenda for Moulage in Simulation". Simulation in Healthcare. 12 (1): 47–50. doi:10.1097/SIH.0000000000000211. ISSN 1559-2332. PMID 28009654. S2CID 19685275.

- Stokes-Parish, Jessica B.; Duvivier, Robbert; Jolly, Brian (2018-05-01). "Investigating the impact of moulage on simulation engagement — A systematic review". Nurse Education Today. 64: 49–55. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2018.01.003. hdl:1959.13/1393355. ISSN 0260-6917. PMID 29459192.

- Robinson, Barry M. "Casualty Simulation Techniques" (PDF). www.vdh.virginia.gov. Retrieved 2022-01-01.

- Mills, Brennen W.; Miles, Alecka K.; Phan, Tina; Dykstra, Peggy M.C.; Hansen, Sara S.; Walsh, Andrew S.; Reid, David N.; Langdon, Claire (April 2018). "Investigating the Extent Realistic Moulage Impacts on Immersion and Performance Among Undergraduate Paramedicine Students in a Simulation-based Trauma Scenario: A Pilot Study". Simulation in Healthcare. 13 (5): 331–340. doi:10.1097/SIH.0000000000000318. ISSN 1559-2332. PMID 29672468. S2CID 4997848.

- Schnabel, Kai; Lörwald, Andrea Carolin; Wüst, Sandra; Bauer, Daniel; Beltraminelli, Helmut (2018). "Modern Medical Moulage in Health Professions Education". University of Maribor, Faculty of Medicine: 22–23. doi:10.7892/boris.113437.

- Howard, M. L.; Shiner, N. (2019-08-01). "The use of simulation and moulage in undergraduate diagnostic radiography education: A burns scenario". Radiography. 25 (3): 194–201. doi:10.1016/j.radi.2018.12.015. ISSN 1078-8174. PMID 31301775. S2CID 81869426.

- Petersen, Christopher (2017). "Optimization of Simulation and Moulage in Military-Related Medical Training" (PDF). Journal of Special Operations Medicine. 17 (3): 74–80. doi:10.55460/X6BB-TZ0C. PMID 28910473. S2CID 12969316 – via JSOM Online.

- Pettitt, M. "Assessment of Tattoo and Silicone Wounds In Terms of Time And Treatment". University of Central Florida.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help)

External links

- Sammlungen International Overview of moulage collections of the Charité Berlin

- Museum of Moulages, University of Zurich (English/ German)

- Jacobi, Eduard (1913) [1903]. Atlas der Hautkrankheiten [Atlas of Skin Diseases] (in German) (5th ed.). Berlin: Urban & Schwarzenberg. OCLC 250681193.

- "Search Our Collection". Museum of Health Care. Retrieved December 3, 2011.

- Gordon, Ken (December 3, 2011). "OSU clinical instructor crafts simulated injuries, giving nursing students a more realistic look at trauma". The Columbus Dispatch. Retrieved December 3, 2011.