Microelectrode array

Microelectrode arrays (MEAs) (also referred to as multielectrode arrays) are devices that contain multiple (tens to thousands) microelectrodes through which neural signals are obtained or delivered, essentially serving as neural interfaces that connect neurons to electronic circuitry. There are two general classes of MEAs: implantable MEAs, used in vivo, and non-implantable MEAs, used in vitro.

Theory

Neurons and muscle cells create ion currents through their membranes when excited, causing a change in voltage between the inside and the outside of the cell. When recording, the electrodes on an MEA transduce the change in voltage from the environment carried by ions into currents carried by electrons (electronic currents). When stimulating, electrodes transduce electronic currents into ionic currents through the media. This triggers the voltage-gated ion channels on the membranes of the excitable cells, causing the cell to depolarize and trigger an action potential if it is a neuron or a twitch if it is a muscle cell.

The size and shape of a recorded signal depend upon several factors: the nature of the medium in which the cell or cells are located (e.g. the medium's electrical conductivity, capacitance, and homogeneity); the nature of contact between the cells and the MEA electrode (e.g. area of contact and tightness); the nature of the MEA electrode itself (e.g. its geometry, impedance, and noise); the analog signal processing (e.g. the system's gain, bandwidth, and behavior outside of cutoff frequencies); and the data sampling properties (e.g. sampling rate and digital signal processing).[1] For the recording of a single cell that partially covers a planar electrode, the voltage at the contact pad is approximately equal to the voltage of the overlapping region of the cell and electrode multiplied by the ratio the surface area of the overlapping region to the area of the entire electrode, or:

assuming the area around an electrode is well-insulated and has a very small capacitance associated with it.[1] The equation above, however, relies on modeling the electrode, cells, and their surroundings as an equivalent circuit diagram. An alternative means of predicting cell-electrode behavior is by modeling the system using a geometry-based finite element analysis in an attempt to circumvent the limitations of oversimplifying the system in a lumped circuit element diagram.[2]

An MEA can be used to perform electrophysiological experiments on tissue slices or dissociated cell cultures. With acute tissue slices, the connections between the cells within the tissue slices prior to extraction and plating are more or less preserved, while the intercellular connections in dissociated cultures are destroyed prior to plating. With dissociated neuronal cultures, the neurons spontaneously form networks.[3]

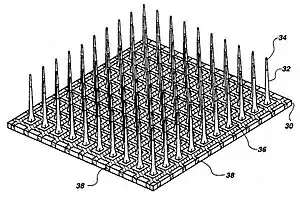

It can be seen that the voltage amplitude an electrode experiences is inversely related to the distance from which a cell depolarizes.[4] Thus, it may be necessary for the cells to be cultured or otherwise placed as close to the electrodes as possible. With tissue slices, a layer of electrically passive dead cells form around the site of incision due to edema.[5] A way to deal with this is by fabricating an MEA with three-dimensional electrodes fabricated by masking and chemical etching. These 3-D electrodes penetrate the dead cell layer of the slice tissue, decreasing the distance between live cells and the electrodes.[6] In dissociated cultures, proper adherence of the cells to the MEA substrate is important for getting robust signals.

History

The first implantable arrays were microwire arrays developed in the 1950s.[7] The first experiment involving the use of an array of planar electrodes to record from cultured cells was conducted in 1972 by C.A. Thomas, Jr. and his colleagues.[4] The experimental setup used a 2 x 15 array of gold electrodes plated with platinum black, each spaced 100 µm apart from each other. Myocytes harvested from embryonic chicks were dissociated and cultured onto the MEAs, and signals up to 1 mV high in amplitude were recorded.[8] MEAs were constructed and used to explore the electrophysiology of snail ganglia independently by Guenter Gross and his colleagues at the Center for Network Neuroscience in 1977 without prior knowledge of Thomas and his colleagues' work.[4] In 1982, Gross observed spontaneous electrophysiological activity from dissociated spinal cord neurons, and found that activity was very dependent on temperature. Below about 30˚C signal amplitudes decrease rapidly to relatively small value at room temperature.[4]

Before the 1990s, significant entry barriers existed for new laboratories that sought to conduct MEA research due to the custom MEA fabrication and software they had to develop.[3] However, with the advent of affordable computing power[1] and commercial MEA hardware and software,[3] many other laboratories were able to undertake research using MEAs.

Types

Microelectrode arrays can be divided up into subcategories based on their potential use: in vitro and in vivo arrays.

In vitro arrays

The standard type of in vitro MEA comes in a pattern of 8 x 8 or 6 x 10 electrodes. Electrodes are typically composed of indium tin oxide or titanium and have diameters between 10 and 30 μm. These arrays are normally used for single-cell cultures or acute brain slices.[1]

One challenge among in vitro MEAs has been imaging them with microscopes that use high power lenses, requiring low working distances on the order of micrometers. In order to avoid this problem, "thin"-MEAs have been created using cover slip glass. These arrays are approximately 180 μm allowing them to be used with high-power lenses.[1][9]

In another special design, 60 electrodes are split into 6 × 5 arrays separated by 500 μm. Electrodes within a group are separated by 30 um with diameters of 10 μm. Arrays such as this are used to examine local responses of neurons while also studying functional connectivity of organotypic slices.[1][10]

Spatial resolution is one of the key advantages of MEAs and allows signals sent over a long distance to be taken with higher precision when a high-density MEA is used. These arrays usually have a square grid pattern of 256 electrodes that cover an area of 2.8 by 2.8 mm.[1]

Increased spatial resolution is provided by CMOS-based high-density microelectrode arrays featuring thousands of electrodes along with integrated readout and stimulation circuits on compact chips of the size of a thumbnail.[11] Even the resolution of signals propagating along single axons has been demonstrated.[12]

In order to obtain quality signals electrodes and tissue must be in close contact with one another. The perforated MEA design applies negative pressure to openings in the substrate so that tissue slices can be positioned on the electrodes to enhance contact and recorded signals.[1]

A different approach to lower the electrode impedance is by modification of the interface material, for example by using carbon nanotubes,[13][14] or by modification of the structure of the electrodes, with for example gold nanopillars[15] or nanocavities.[16]

In vivo arrays

The three major categories of implantable MEAs are microwire, silicon-based,[17] and flexible microelectrode arrays. Microwire MEAs are largely made of stainless steel or tungsten and they can be used to estimate the position of individual recorded neurons by triangulation. Silicon-based microelectrode arrays include two specific models: the Michigan and Utah arrays. Michigan arrays allow a higher density of sensors for implantation as well as a higher spatial resolution than microwire MEAs. They also allow signals to be obtained along the length of the shank, rather than just at the ends of the shanks. In contrast to Michigan arrays, Utah arrays are 3-D, consisting of 100 conductive silicon needles. However, in a Utah array, signals are only received from the tips of each electrode, which limits the amount of information that can be obtained at one time. Furthermore, Utah arrays are manufactured with set dimensions and parameters while the Michigan array allows for more design freedom. Flexible arrays, made with polyimide, parylene, or benzocyclobutene, provide an advantage over rigid microelectrode arrays because they provide a closer mechanical match, as the Young's modulus of silicon is much larger than that of brain tissue, contributing to shear-induced inflammation.[7]

Data processing methods

The fundamental unit of communication of neurons is, electrically, at least, the action potential. This all-or-nothing phenomenon originates at the axon hillock,[18] resulting in a depolarization of the intracellular environment which propagates down the axon. This ion flux through the cellular membrane generates a sharp change in voltage in the extracellular environment, which is what the MEA electrodes ultimately detect. Thus, voltage spike counting and sorting is often used in research to characterize network activity. Spike train analysis, can also save processing time and computing memory compared to voltage measurements. Spike timestamps are identified as times where the voltage measured by an individual electrode exceeds a threshold (often defined by standard deviations from the mean of an inactive time period). These timestamps can be further processed to identify bursts(multiple spikes in close proximity). Further analysis of these trains can reveal spike organization and temporal patterns.[19]

Capabilities

Advantages

In general, the major strengths of in vitro arrays when compared to more traditional methods such as patch clamping include:[20]

- Allowing the placement of multiple electrodes at once rather than individually

- The ability to set up controls within the same experimental setup (by using one electrode as a control and others as experimental). This is of particular interest in stimulation experiments.

- The ability to select different recordings sites within the array

- The ability to simultaneously receive data from multiple sites

- Recordings from intact retinae are of great interest because of the possibility of delivering real-time optical stimulation and, for instance, the possibility of reconstructing receptive fields.

Furthermore, in vitro arrays are non-invasive when compared to patch clamping because they do not require breaching of the cell membrane.

With respect to in vivo arrays however, the major advantage over patch clamping is the high spatial resolution. Implantable arrays allow signals to be obtained from individual neurons enabling information such as position or velocity of motor movement that can be used to control a prosthetic device. Large-scale, parallel recordings with tens of implanted electrodes are possible, at least in rodents, during animal behavior. This makes such extracellular recordings the method of choice to identify of neural circuits and to study their functions. Unambiguous identification of the recorded neuron using multi-electrode extracellular arrays, however, remains a problem to date.

Disadvantages

In vitro MEAs are less suited for recording and stimulating single cells due to their low spatial resolution compared to patch clamp and dynamic clamp systems. The complexity of signals an MEA electrode could effectively transmit to other cells is limited compared to the capabilities of dynamic clamps.

There are also several biological responses to implantation of a microelectrode array, particularly in regards to chronic implantation. Most notable among these effects are neuronal cell loss, glial scarring, and a drop in the number of functioning electrodes.[21] The tissue response to implantation is dependent among many factors including size of the MEA shanks, distance between the shanks, MEA material composition, and time period of insertion. The tissue response is typically divided into short term and long term response. The short term response occurs within hours of implantation and begins with an increased population of astrocytes and glial cells surrounding the device. The recruited microglia then initiate inflammation and a process of phagocytosis of the foreign material begins. Over time, the astrocytes and microglia recruited to the device begin to accumulate, forming a sheath surrounding the array that extends tens of micrometres around the device. This not only increases the space between electrode probes, but also insulates the electrodes and increases impedance measurements. Problems with chronic implantation of arrays have been a driving force in the research of these devices. One novel study examined the neurodegenerative effects of inflammation caused by chronic implantation.[22] Immunohistochemical markers showed a surprising presence of hyperphosphorylated tau, an indicator of Alzheimer's disease, near the electrode recording site. The phagocytosis of electrode material also brings into question the issue of a biocompatibility response, which research suggests has been minor and becomes almost nonexistent after 12 weeks in vivo. Research into minimizing the negative effects of device insertion includes surface coating of the devices with proteins that encourage neuron attachment, such as laminin, or drug eluting substances.[23]

Applications

In vitro

The nature of dissociated neuronal networks does not seem to change or diminish the character of its pharmacological response when compared to in vivo models, suggesting that MEAs can be used to study pharmacological effects on dissociated neuronal cultures in a more simple, controlled environment.[24] A number of pharmacological studies using MEAs on dissociated neuronal networks, e.g. studies with ethanol.[25] Interlaboratory validation has been conducted using MEAs.[26]

In addition, a substantial body of work on various biophysical aspects of network function was carried out by reducing phenomena usually studied at the behavioral level to the dissociated cortical network level. For example, the capacity of such networks to extract spatial[27] and temporal[28] features of various input signals, dynamics of synchronization,[29] sensitivity to neuromodulation[30][31][32] and kinetics of learning using closed loop regimes.[33][34] Finally, combining MEA technology with confocal microscopy allows for studying relationships between network activity and synaptic remodeling.[9]

MEAs have been used to interface neuronal networks with non-biological systems as a controller. For example, a neural-computer interface can be created using MEAs. Dissociated rat cortical neurons were integrated into a closed stimulus-response feedback loop to control an animat in a virtual environment.[35] A closed-loop stimulus-response system has also been constructed using an MEA by Potter, Mandhavan, and DeMarse,[36] and by Mark Hammond, Kevin Warwick, and Ben Whalley in the University of Reading. About 300,000 dissociated rat neurons were plated on an MEA, which was connected to motors and ultrasound sensors on a robot, and was conditioned to avoid obstacles when sensed.[37] Along these lines, Shimon Marom and colleagues in the Technion hooked dissociated neuronal networks growing on MEAs to a Lego Mindstorms robot; the visual field of the robot was classified by the network, and commands were delivered to the robot wheels such that it completely avoids bumping into obstacles.[27] This "Braitenberg vehicle" was used to demonstrate the indeterminacy of reverse neuro-engineering showing that even in a simple setup with practically unlimited access to every piece of relevant information,[38] it was impossible to deduce with certainty the specific neural coding scheme that was used to drive the robots behavior.

MEAs have been used to observe network firing in hippocampal slices.[39]

In vivo

There are several implantable interfaces that are currently available for consumer use including deep brain stimulators, cochlear implants, and cardiac pacemakers. Deep brain stimulation (DBS) has been effective at treating movement disorders such as Parkinson's disease,[40] and cochlear implants have helped many to improve their hearing by assisting stimulation of the auditory nerve. Because of their remarkable potential, MEAs are a prominent area of neuroscience research. Research suggests that MEAs may provide insight into processes such as memory formation and perception and may also hold therapeutic value for conditions such as epilepsy, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder . Clinical trials using interface devices for restoring motor control after spinal cord injury or as treatment for ALS have been initiated in a project entitled BrainGate (see video demo: BrainGate). MEAs provide the high resolution necessary to record time varying signals, giving them the ability to be used to both control and obtain feedback from prosthetic devices, as was shown by Kevin Warwick, Mark Gasson and Peter Kyberd.[41][42] Research suggests that MEA use may be able to assist in the restoration of vision by stimulating the optic pathway.[7]

MEA user meetings

A biannual scientific user meeting is held in Reutlingen, organized by the Natural and Medical Sciences Institute (NMI) at the University of Tübingen. The meetings offer a comprehensive overview of all aspects related to new developments and current applications of Microelectrode Arrays in basic and applied neuroscience as well as in industrial drug discovery, safety pharmacology and neurotechnology. The biannual conference has developed into an international venue for scientists developing and using MEAs from both industry and academia, and is recognized as an information-packed scientific forum of high quality. The meeting contributions are available as open access proceeding books.

Use in art

In addition to being used for scientific purposes, MEAs have been used in contemporary art to investigate philosophical questions about the relationship between technology and biology. Traditionally within Western thought, biology and technology have been separated into two distinct categories: bios and technê.[43] In 2002, MEART: The Semi-living Artist was created as a collaborative art and science project between SymbioticA at the University of Western Australia in Perth, and the Potter Lab at the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta, to question the relationship between biology and technology.[44][45][46][47] MEART consisted of rat cortical neurons grown in vitro on an MEA in Atlanta, a pneumatic robot arm capable of drawing with pens on paper in Perth, and software to govern communications between the two. Signals from the neurons were relayed in a closed-loop between Perth and Atlanta as the MEA stimulated the pneumatic arm. MEART was first exhibited to the public in the exhibition Biofeel at the Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts in 2002.[46][48]

See also

- Animat

- Artificial cardiac pacemaker

- Deep brain stimulation

- Patch clamp

- Bioelectronics

References

- Boven, K.-H.; Fejtl, M.; Möller, A.; Nisch, W.; Stett, A. (2006). "On Micro-Electrode Array Revival". In Baudry, M.; Taketani, M. (eds.). Advances in Network Electrophysiology Using Multi-Electrode Arrays. New York: Springer. pp. 24–37. ISBN 0-387-25857-4.

- Buitenweg, J. R.; Rutten, W. L.; Marani, E. (2003). "Geometry-based finite element modeling of the electrical contact between a cultured neuron and a microelectrode". IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 50 (4): 501–509. doi:10.1109/TBME.2003.809486. PMID 12723062. S2CID 15578217.

- Potter, S. M. (2001). "Distributed processing in cultured neuronal networks". Prog Brain Res. Progress in Brain Research. Vol. 130. pp. 49–62. doi:10.1016/S0079-6123(01)30005-5. PMID 11480288.

- Pine, J. (2006). "A History of MEA Development". In Baudry, M.; Taketani, M. (eds.). Advances in Network Electrophysiology Using Multi-Electrode Arrays. New York: Springer. pp. 3–23. ISBN 0-387-25857-4.

- Heuschkel, M. O.; Wirth, C.; Steidl, E. M.; Buisson, B. (2006). "A History of MEA Development". In Baudry, M.; Taketani, M. (eds.). Advances in Network Electrophysiology Using Multi-Electrode Arrays. New York: Springer. pp. 69–111. ISBN 0-387-25857-4.

- Thiebaud, P.; deRooij, N. F.; Koudelka-Hep, M.; Stoppini, L. (1997). "Microelectrode arrays for electrophysiological monitoring of hippocampal organotypic slice cultures". IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 44 (11): 1159–63. doi:10.1109/10.641344. PMID 9353996. S2CID 22179940.

- Cheung, K. C. (2007). "Implantable microscale neural interfaces". Biomedical Microdevices. 9 (6): 923–38. doi:10.1007/s10544-006-9045-z. PMID 17252207. S2CID 37347927.

- Thomas, C. A.; Springer, P. A.; Loeb, G. E.; Berwald-Netter, Y.; Okun, L. M. (1972). "A miniature microelectrode array to monitor the bioelectric activity of cultured cells". Exp. Cell Res. 74 (1): 61–66. doi:10.1016/0014-4827(72)90481-8. PMID 4672477.

- Minerbi, A.; Kahana, R.; Goldfeld, L.; Kaufman, M.; Marom, S.; Ziv, N. E. (2009). "Long-term relationships between synaptic tenacity, synaptic remodeling, and network activity". PLOS Biol. 7 (6): e1000136. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000136. PMC 2693930. PMID 19554080.

- Segev, R.; Berry II, M. J. (2003). "Recording from all of the ganglion cells in the retina". Soc Neurosci Abstr. 264: 11.

- Hierlemann, A.; Frey, U.; Hafizovic, S.; Heer, F. (2011). "Growing Cells atop Microelectronic Chips: Interfacing Electrogenic Cells in Vitro with CMOS-based Microelectrode Arrays". Proceedings of the IEEE. 99 (2): 252–284. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2010.2066532. S2CID 2578216.

- Bakkum, D. J.; Frey, U.; Radivojevic, M.; Russell, T. L.; Müller, J.; Fiscella, M.; Takahashi, H.; Hierlemann, A. (2013). "Tracking axonal action potential propagation on a high-density microelectrode array across hundreds of sites". Nature Communications. 4: 2181. Bibcode:2013NatCo...4.2181B. doi:10.1038/ncomms3181. PMC 5419423. PMID 23867868.

- Yu, Z.; et al. (2007). "Vertically Aligned Carbon Nanofiber Arrays Record Electrophysiological Signals from Hippocampal Slices". Nano Lett. 7 (8): 2188–95. Bibcode:2007NanoL...7.2188Y. doi:10.1021/nl070291a. PMID 17604402.

- Gabay, T.; et al. (2007). "Electro-chemical and biological properties of carbon nanotube based multi-electrode arrays". Nanotechnology. 18 (3): 035201. Bibcode:2007Nanot..18c5201G. doi:10.1088/0957-4484/18/3/035201. PMID 19636111.

- Brüggemann, D.; et al. (2011). "Nanostructured gold microelectrodes for extracellular recording from electrogenic cells". Nanotechnology. 22 (26): 265104. Bibcode:2011Nanot..22z5104B. doi:10.1088/0957-4484/22/26/265104. PMID 21586820.

- Hofmann, B.; et al. (2011). "Nanocavity electrode array for recording from electrogenic cells". Lab Chip. 11 (6): 1054–8. doi:10.1039/C0LC00582G. PMID 21286648.

- Bhandari, R.; Negi, S.; Solzbacher, F. (2010). "Wafer Scale Fabrication of Penetrating Neural Electrode Arrays". Biomedical Microdevices. 12 (5): 797–807. doi:10.1007/s10544-010-9434-1. PMID 20480240. S2CID 25288723.

- Angelides, K. J.; Elmer, L. W.; Loftus, D.; Elson, E. (1988). "Distribution and lateral mobility of voltage-dependent sodium channels in neurons". J. Cell Biol. 106 (6): 1911–25. doi:10.1083/jcb.106.6.1911. PMC 2115131. PMID 2454930.

- Dastgheyb, Raha M.; Yoo, Seung-Wan; Haughey, Norman J. (2020). "MEAnalyzer – a Spike Train Analysis Tool for Multi Electrode Arrays". Neuroinformatics. 18 (1): 163–179. doi:10.1007/s12021-019-09431-0. PMID 31273627. S2CID 195795810.

- Whitson, J.; Kubota, D.; Shimono, K.; Jia, Y.; Taketani, M. (2006). "Multi-Electrode Arrays: Enhancing Traditional Methods and Enabling Network Physiology". In Baudry, M.; Taketani, M. (eds.). Advances in Network Electrophysiology Using Multi-Electrode Arrays. New York: Springer. pp. 38–68. ISBN 0-387-25857-4.

- Biran, R.; Martin, D. C.; Tresco, P. A. (2005). "Neuronal cell loss accompanies the brain tissue response to chronically implanted silicon microelectrode arrays". Experimental Neurology. 195 (1): 115–26. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.04.020. PMID 16045910. S2CID 14077903.

- McConnell GC, Rees HD, Levey AI, Gross RG, Bellamkonda RV. 2008. Chronic electrodes induce a local, neurodegenerative state: Implications for chronic recording reliability. Society for Neuroscience, Washington, D.C

- He, W.; McConnell, G. C.; Bellamkonda, R. V. (2006). "Nanoscale laminin coating modulates cortical scarring response around implanted silicon microelectrode arrays". Journal of Neural Engineering. 3 (4): 316–26. Bibcode:2006JNEng...3..316H. doi:10.1088/1741-2560/3/4/009. PMID 17124336.

- Gopal, K. V.; Gross, G. W. (2006). "Emerging Histotypic Properties of Cultured Neuronal Networks". In Baudry, M.; Taketani, M. (eds.). Advances in Network Electrophysiology Using Multi-Electrode Arrays. New York: Springer. pp. 193–214. ISBN 0-387-25857-4.

- Xia, Y. & Gross, G. W. (2003). "Histotypic electrophysiological responses of cultured neuronal networks to ethanol". Alcohol. 30 (3): 167–74. doi:10.1016/S0741-8329(03)00135-6. PMID 13679110.

- Novellino, A; Scelfo, B; Palosaari, T; Price, A; Sobanski, T; Shafer, T; Johnstone, A; Gross, G; Gramowski, A; Scroeder, O; Jügelt, K; Chiappalone, M; Benfenati, F; Martinoia, S; Tedesco, M; Defranchi, E; D'Angelo, P; Whelan, M (April 27, 2011). "Development of micro-electrode array based tests for neurotoxicity: assessment of interlaboratory reproducibility with neuroactive chemicals". Front. Neuroeng. 4 (4): 4. doi:10.3389/fneng.2011.00004. PMC 3087164. PMID 21562604.

- Shahaf, G.; Eytan, D.; Gal, A.; Kermany, E.; Lyakhov, V.; Zrenner, C.; Marom, S. (2008). "Order-based representation in random networks of cortical neurons". PLOS Comput. Biol. 4 (11): e1000228. Bibcode:2008PLSCB...4E0228S. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000228. PMC 2580731. PMID 19023409.

- Eytan, D.; Brenner, N.; Marom, S. (2003). "Selective adaptation in networks of cortical neurons". J. Neurosci. 23 (28): 9349–9356. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-28-09349.2003. PMC 6740578. PMID 14561862.

- Eytan, D.; Marom, S. (2006). "Dynamics and effective topology underlying synchronization in networks of cortical neurons". J. Neurosci. 26 (33): 8465–8476. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1627-06.2006. PMC 6674346. PMID 16914671.

- Eytan, D.; Minerbi, A.; Ziv, N. E.; Marom, S. (2004). "Dopamine-induced dispersion of correlations between action potentials in networks of cortical neurons". J Neurophysiol. 92 (3): 1817–1824. doi:10.1152/jn.00202.2004. PMID 15084641.

- Tateno, T.; Jimbo, Y.; Robinson, H. P. (2005). "Spatio-temporal cholinergic modulation in cultured networks of rat cortical neurons: spontaneous activity". Neuroscience. 134 (2): 425–437. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.04.049. PMID 15993003. S2CID 22745827.

- Tateno, T.; Jimbo, Y.; Robinson, H. P. (2005). "Spatio-temporal cholinergic modulation in cultured networks of rat cortical neurons: evoked activity". Neuroscience. 134 (2): 439–448. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.04.055. PMID 15979809. S2CID 6922531.

- Shahaf, G.; Marom, S. (2001). "Learning in networks of cortical neurons". J. Neurosci. 21 (22): 8782–8788. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-22-08782.2001. PMC 6762268. PMID 11698590.

- Stegenga, J.; Le Feber, J.; Marani, E.; Rutten, W. L. (2009). "The effect of learning on bursting". IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 56 (4): 1220–1227. doi:10.1109/TBME.2008.2006856. PMID 19272893. S2CID 12379440.

- DeMarse, T. B.; Wagenaar, D. A.; Blau, A. W.; Potter, S. M. (2001). "The Neurally Controlled Animat: Biological Brains Acting with Simulated Bodies". Autonomous Robots. 11 (3): 305–10. doi:10.1023/A:1012407611130. PMC 2440704. PMID 18584059.

- Potter, S. M.; Madhavan, R.; DeMarse, T. B. (2003). "Long-term bidirectional neuron interfaces for robotic control, and in vitro learning studies". Proc. 25th IEEE EMBS Annual Meeting: 3690–3693. doi:10.1109/IEMBS.2003.1280959. ISBN 0-7803-7789-3. S2CID 12213854.

- Marks, P. (2008). "Rise of the rat-brained robots". New Scientist. 199 (2669): 22–23. doi:10.1016/S0262-4079(08)62062-X.

- Marom, S.; Meir, R.; Braun, E.; Gal, A.; Kermany, E.; Eytan, D. (2009). "On the precarious path of reverse neuro-engineering". Front Comput Neurosci. 3: 5. doi:10.3389/neuro.10.005.2009. PMC 2691154. PMID 19503751.

- Colgin, L. L.; Kramar, E. A.; Gall, C. M.; Lynch, G. (2003). "Septal modulation of excitatory transmission in hippocampus". J Neurophysiol. 90 (4): 2358–2366. doi:10.1152/jn.00262.2003. PMID 12840078.

- Breit, S.; Schulz, J. B.; Benabid, A. L. (2004). "Deep Brain Stimulation". Cell and Tissue Research. 318 (1): 275–288. doi:10.1007/s00441-004-0936-0. PMID 15322914. S2CID 25263765.

- Warwick, K.; Gasson, M.; Hutt, B.; Goodhew, I.; Kyberd, P.; Andrews, B.; Teddy, P.; Shad, A. (2003). "The Application of Implant Technology for Cybernetic Systems". Archives of Neurology. 60 (10): 1369–1373. doi:10.1001/archneur.60.10.1369. PMID 14568806.

- Schwartz, A. B. (2004). "Cortical Neural Prosthetics". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 27: 487–507. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144233. PMID 15217341.

- Thacker, Eugene (2010) "What is Biomedia?" in "Critical Terms for Media Studies" University of Chicago Press. Chicago and London, pp118-30

- Bakkum DJ, Gamblen PM, Ben-Ary G, Chao ZC, Potter SM (2007). "MEART: The Semi-Living Artist". Frontiers in Neurorobotics. 1: 5. doi:10.3389/neuro.12.005.2007. PMC 2533587. PMID 18958276.

- Bakkum, Douglas J.; Shkolnik, Alexander C.; Ben-Ary, Guy; Gamblen, Phil; DeMarse, Thomas B.; Potter, Steve M. (2004). Removing Some 'A' from AI: Embodied Cultured Networks. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 3139. pp. 130–45. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-27833-7_10. ISBN 978-3-540-22484-6.

- SymbioticA research Group (2002) MEART – the semi living artist (AKA Fish & Chips) Stage 2 pp.60-68. in BEAP, Biennale of Electronic Art, 2002: The Exhibitions. Thomas, Paul, Ed., Pub. Curtin University. ISBN 1 74067 157 0.

- Ben-Ary, G, Zurr, I, Richards, M, Gamblen, P, Catts, O and Bunt, S (2001) “Fish and Chips, The current Status of the Research by the SymbioticA research group” in Takeover, wer macht die Kunst von morgen (who's doing the art of tomorrow) pp. 141-147 Springer Vien.

- "BioFeel: biology + art". Perth Institute for Contemporary Art. Archived from the original on 2014-08-11.