Myocardial infarction diagnosis

A diagnosis of myocardial infarction is created by integrating the history of the presenting illness and physical examination with electrocardiogram findings and cardiac markers (blood tests for heart muscle cell damage).[1][2] A coronary angiogram allows visualization of narrowings or obstructions on the heart vessels, and therapeutic measures can follow immediately. At autopsy, a pathologist can diagnose a myocardial infarction based on anatomopathological findings.

| Myocardial infarction diagnosis | |

|---|---|

| Purpose | Diagnose myocardial infarct via physical exam and EKG (plus blood test) |

A chest radiograph and routine blood tests may indicate complications or precipitating causes and are often performed upon arrival to an emergency department. New regional wall motion abnormalities on an echocardiogram are also suggestive of a myocardial infarction. Echo may be performed in equivocal cases by the on-call cardiologist.[3] In stable patients whose symptoms have resolved by the time of evaluation, Technetium (99mTc) sestamibi (i.e. a "MIBI scan"), thallium-201 chloride or Rubidium-82 Chloride can be used in nuclear medicine to visualize areas of reduced blood flow in conjunction with physiologic or pharmocologic stress.[3][4] Thallium may also be used to determine viability of tissue, distinguishing whether non-functional myocardium is actually dead or merely in a state of hibernation or of being stunned.[5]

Diagnostic criteria

According to the WHO criteria as revised in 2000,[6] a cardiac troponin rise accompanied by either typical symptoms, pathological Q waves, ST elevation or depression or coronary intervention are diagnostic of MI.

Previous WHO criteria[7] formulated in 1979 put less emphasis on cardiac biomarkers; according to these, a patient is diagnosed with myocardial infarction if two (probable) or three (definite) of the following criteria are satisfied:

- Clinical history of ischaemic type chest pain lasting for more than 20 minutes

- Changes in serial ECG tracings

- Rise and fall of serum cardiac biomarkers such as creatine kinase-MB fraction and troponin

Physical examination

The general appearance of patients may vary according to the experienced symptoms; the patient may be comfortable, or restless and in severe distress with an increased respiratory rate. A cool and pale skin is common and points to vasoconstriction. Some patients have low-grade fever (38–39 °C). Blood pressure may be elevated or decreased, and the pulse can become irregular.[8][9]

If heart failure ensues, elevated jugular venous pressure and hepatojugular reflux, or swelling of the legs due to peripheral edema may be found on inspection. Rarely, a cardiac bulge with a pace different from the pulse rhythm can be felt on precordial examination. Various abnormalities can be found on auscultation, such as a third and fourth heart sound, systolic murmurs, paradoxical splitting of the second heart sound, a pericardial friction rub and rales over the lung.[8][10]

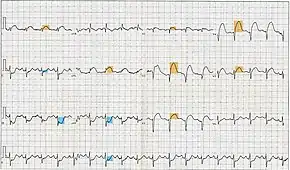

Electrocardiogram

The primary purpose of the electrocardiogram is to detect ischemia or acute coronary injury in broad, symptomatic emergency department populations. A serial ECG may be used to follow rapid changes in time. The standard 12 lead ECG does not directly examine the right ventricle, and is relatively poor at examining the posterior basal and lateral walls of the left ventricle. In particular, acute myocardial infarction in the distribution of the circumflex artery is likely to produce a nondiagnostic ECG.[11] The use of additional ECG leads like right-sided leads V3R and V4R and posterior leads V7, V8, and V9 may improve sensitivity for right ventricular and posterior myocardial infarction.

The 12 lead ECG is used to classify patients into one of three groups:[12]

- those with ST segment elevation or new bundle branch block (suspicious for acute injury and a possible candidate for acute reperfusion therapy with thrombolytics or primary PCI),

- those with ST segment depression or T wave inversion (suspicious for ischemia), and

- those with a so-called non-diagnostic or normal ECG.

A normal ECG does not rule out acute myocardial infarction. Mistakes in interpretation are relatively common, and the failure to identify high risk features has a negative effect on the quality of patient care.[13]

It should be determined if a person is at high risk for myocardial infarction before conducting imaging tests to make a diagnosis.[14] People who have a normal ECG and who are able to exercise, for example, do not merit routine imaging.[14] Imaging tests such as stress radionuclide myocardial perfusion imaging or stress echocardiography can confirm a diagnosis when a person's history, physical exam, ECG and cardiac biomarkers suggest the likelihood of a problem.[14]

Cardiac markers

Cardiac markers or cardiac enzymes are proteins that leak out of injured myocardial cells through their damaged cell membranes into the bloodstream. Until the 1980s, the enzymes SGOT and LDH were used to assess cardiac injury. Now, the markers most widely used in detection of MI are MB subtype of the enzyme creatine kinase and cardiac troponins T and I as they are more specific for myocardial injury. The cardiac troponins T and I which are released within 4–6 hours of an attack of MI and remain elevated for up to 2 weeks, have nearly complete tissue specificity and are now the preferred markers for assessing myocardial damage.[15] Heart-type fatty acid binding protein is another marker, used in some home test kits. Elevated troponins in the setting of chest pain may accurately predict a high likelihood of a myocardial infarction in the near future.[16] New markers such as glycogen phosphorylase isoenzyme BB are under investigation.[17]

The diagnosis of myocardial infarction requires two out of three components (history, ECG, and enzymes). When damage to the heart occurs, levels of cardiac markers rise over time, which is why blood tests for them are taken over a 24-hour period. Because these enzyme levels are not elevated immediately following a heart attack, patients presenting with chest pain are generally treated with the assumption that a myocardial infarction has occurred and then evaluated for a more precise diagnosis.[18]

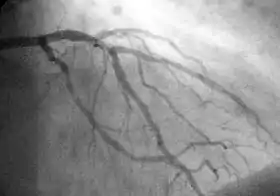

Angiography

In difficult cases or in situations where intervention to restore blood flow is appropriate, coronary angiography can be performed. A catheter is inserted into an artery (typically the radial or femoral artery[19]) and pushed to the vessels supplying the heart. A radio-opaque dye is administered through the catheter and a sequence of x-rays (fluoroscopy) is performed. Obstructed or narrowed arteries can be identified, and angioplasty applied as a therapeutic measure (see below). Angioplasty requires extensive skill, especially in emergency settings. It is performed by a physician trained in interventional cardiology.

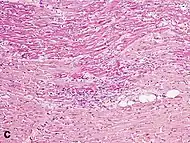

Histopathology

Histopathological examination of the heart may reveal infarction at autopsy. Gross examination may reveal signs of myocardial infarction.

A one-week-old myocardial infarction of the posterior left ventricle, with focal rupture, in fresh state (left) and after formalin fixation (right). The infarcted area is pale whereas the rupture is hemorrhagic (dark red).

A one-week-old myocardial infarction of the posterior left ventricle, with focal rupture, in fresh state (left) and after formalin fixation (right). The infarcted area is pale whereas the rupture is hemorrhagic (dark red). Cross-section of the heart, showing an old myocardial infarction of the posterior wall of the left ventricle (seen as pale areas).

Cross-section of the heart, showing an old myocardial infarction of the posterior wall of the left ventricle (seen as pale areas).

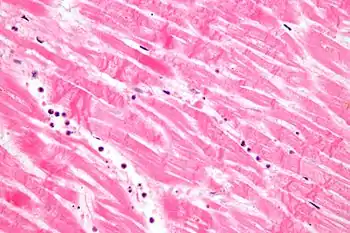

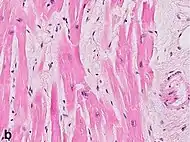

Under the microscope, myocardial infarction presents as a circumscribed area of ischemic, coagulative necrosis (cell death). On gross examination, the infarct is not identifiable within the first 12 hours.[20]

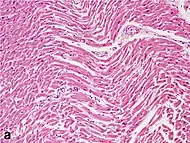

Although earlier changes can be discerned using electron microscopy, one of the earliest changes under a normal microscope are so-called wavy fibers.[21] Subsequently, the myocyte cytoplasm becomes more eosinophilic (pink) and the cells lose their transversal striations, with typical changes and eventually loss of the cell nucleus.[22] The interstitium at the margin of the infarcted area is initially infiltrated with neutrophils, then with lymphocytes and macrophages, who phagocytose ("eat") the myocyte debris. The necrotic area is surrounded and progressively invaded by granulation tissue, which will replace the infarct with a fibrous (collagenous) scar (which are typical steps in wound healing). The interstitial space (the space between cells outside of blood vessels) may be infiltrated with red blood cells.[20]

These features can be recognized in cases where the perfusion was not restored; reperfused infarcts can have other hallmarks, such as contraction band necrosis.[23]

These tables gives an overview of the histopathology seen in myocardial infarction by time after obstruction.

By individual parameters

| Myocardial histologic parameters (HE staining)[24] | Earliest manifestation[24] | Full development[24] | Decrease/disappearance[24] | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stretched/wavy fibres | 1–2 h |  | ||

| Coagulative necrosis: cytoplasmic hypereosinophilia | 1–3 h | 1–3 days; cytoplasmic hypereosinophilia and loss of striations | > 3 days: disintegration |  |

| Interstitial edema | 4–12 h |  | ||

| Coagulative necrosis: 'nuclear changes' | 12–24 (pyknosis, karyorrhexis) | 1–3 days (loss of nuclei) | Depends on size of infarction |  |

| Neutrophil infiltration | 12–24 h | 1–3 days | 5–7 days |  |

| Karyorrhexis of neutrophils | 1.5–2 days | 3–5 days |  | |

| Macrophages and lymphocytes | 3–5 days | 5–10 days (including 'siderophages') | 10 days to 2 months |  |

| Vessel/endothelial sprouts* | 5–10 days | 10 days–4 weeks | 4 weeks: disappearance of capillaries; some large dilated vessels persist |  |

| Fibroblast and young collagen* | 5–10 days | 2–4 weeks | After 4 weeks; depends on size of infarction; |  |

| Dense fibrosis | 4 weeks | 2–3 months | No |  |

- Some authors summarize the vascular and early fibrotic changes as 'granulation tissue', which is maximal at 2–3 weeks

Differential diagnoses for myocardial fibrosis:

- Interstitial fibrosis, which is nonspecific, having been described in congestive heart failure, hypertension, and normal aging.[25]

- Subepicardial fibrosis, which is associated with non-infarction diagnoses such as myocarditis[26] and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy.[27]

Healthy myocardium versus interstitial fibrosis in dilated cardiomyopathy. Alcian blue stain.

Healthy myocardium versus interstitial fibrosis in dilated cardiomyopathy. Alcian blue stain. Subepicardial fibrosis (epicardium at top)

Subepicardial fibrosis (epicardium at top)

Chronological

| Time | Gross examination | Histopathology by light microscopy |

|---|---|---|

| 0 - 0.5 hours | None[note 1] | None[note 1] |

| 0.5 – 4 hours | None[note 2] |

|

| 4 – 12 hours |

|

|

| 12 – 24 hours |

|

|

| 1 – 3 days |

|

|

| 3 – 7 days |

|

|

| 7 – 10 days |

|

|

| 10 – 14 days |

|

|

| 2 – 8 weeks |

|

|

| More than 2 months | Completed scarring[note 3] | Dense collagenous scar formed[note 3] |

| If not else specified in boxes, then reference is nr[29] | ||

Notes

- For the first ~30 minutes no change at all can be seen by gross examination or by light microscopy in histopathology. However, in electron microscopy relaxed myofibrils, as well as glycogen loss and mitochondrial swelling can be observered.

- It is often possible, however, to highlight the area of necrosis that first becomes apparent after 2 to 3 hours by immersion of tissue slices in a solution of triphenyltetrazolium chloride. This dye imparts a brick-red color to intact, noninfarcted myocardium where the dehydrogenase activity is preserved. Because dehydrogenases are depleted in the area of ischemic necrosis (i.e., they leak out through the damaged cell membranes), an infarcted area is revealed as an unstained pale zone. Instead of a triphenyltetrazolium chloride dye, a LDH (lactate dehydrogenase) dye can also be used to visualize an area of necrosis.

- Once scarring is completed, there is yet no common method of discerning the actual age of the infarct, since e.g. a scar that is four months old looks identical to a scar that is ten years old.

References

- Mallinson, T (2010). "Myocardial Infarction". Focus on First Aid (15): 15. Archived from the original on 2010-05-21. Retrieved 2010-06-08.

- Myocardial infarction: diagnosis and investigations – GPnotebook, retrieved November 27, 2006.

- DE Fenton et al. Myocardial infarction – eMedicine, retrieved November 27, 2006.

- HEART SCAN Archived 2009-02-16 at the Wayback Machine – Patient information from University College London. Retrieved November 27, 2006.

- Skoufis E, McGhie AI (1998). "Radionuclide techniques for the assessment of myocardial viability". Tex Heart Inst J. 25 (4): 272–9. PMC 325572. PMID 9885104.

- Alpert JS, Thygesen K, Antman E, Bassand JP (2000). "Myocardial infarction redefined--a consensus document of The Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the redefinition of myocardial infarction". J Am Coll Cardiol. 36 (3): 959–69. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(00)00804-4. PMID 10987628.

- Anonymous (March 1979). "Nomenclature and criteria for diagnosis of ischemic heart disease. Report of the Joint International Society and Federation of Cardiology/World Health Organization task force on standardization of clinical nomenclature". Circulation. 59 (3): 607–9. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.59.3.607. PMID 761341.

- S. Garas et al.. Myocardial Infarction. eMedicine. Retrieved November 22, 2006.

- Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. p. 1444. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2005. ISBN 0-07-139140-1.

- Kasper DL, et al. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. p. 1450.

- Cannon CP at al. Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes. p. 175. New Jersey: Humana Press, 1999. ISBN 0-89603-552-2.

- Ecc Committee, Subcommittees Task Forces of the American Heart Association (2005). "2005 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care — Part 8: Stabilization of the Patient With Acute Coronary Syndromes". Circulation. 112 (24 Suppl): IV–89–IV–110. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.166561. PMID 16314375.

- Masoudi FA, Magid DJ, Vinson DR, et al. (October 2006). "Implications of the failure to identify high-risk electrocardiogram findings for the quality of care of patients with acute myocardial infarction: results of the Emergency Department Quality in Myocardial Infarction (EDQMI) study". Circulation. 114 (15): 1565–71. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.623652. PMID 17015790.

- American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question" (PDF), Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, archived from the original (PDF) on April 16, 2012, retrieved August 17, 2012, which cites

- Hendel, R. C.; Berman, D. S.; Di Carli, M. F.; Heidenreich, P. A.; Henkin, R. E.; Pellikka, P. A.; Pohost, G. M.; Williams, K. A.; American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force; American Society of Nuclear Cardiology; American College Of, R.; American Heart, A.; American Society of Echocardiology; Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography; Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance; Society Of Nuclear, M. (2009). "ACCF/ASNC/ACR/AHA/ASE/SCCT/SCMR/SNM 2009 Appropriate Use Criteria for Cardiac Radionuclide Imaging". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 53 (23): 2201–2229. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.013. PMID 19497454.

- Taylor, A. J.; Cerqueira, M.; Hodgson, J. M. .; Mark, D.; Min, J.; O'Gara, P.; Rubin, G. D.; American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force; Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography; American College Of, R.; American Heart, A.; American Society of Echocardiography; American Society of Nuclear Cardiology; North American Society for Cardiovascular Imaging; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography Interventions; Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance; Kramer, C. M.; Berman; Brown; Chaudhry, F. A.; Cury, R. C.; Desai, M. Y.; Einstein, A. J.; Gomes, A. S.; Harrington, R.; Hoffmann, U.; Khare, R.; Lesser; McGann; Rosenberg, A. (2010). "ACCF/SCCT/ACR/AHA/ASE/ASNC/NASCI/SCAI/SCMR 2010 Appropriate Use Criteria for Cardiac Computed Tomography". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 56 (22): 1864–1894. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.07.005. PMID 21087721.

- Anderson, J. L.; Adams, C. D.; Antman, E. M.; Bridges, C. R.; Califf, R. M.; Casey, D. E.; Chavey, W. E.; Fesmire, F. M.; Hochman, J. S.; Levin, T. N.; Lincoff, A. M.; Peterson, E. D.; Theroux, P.; Wenger, N. K.; Wright, R. S. (2007). "ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction): Developed in Collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons: Endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine". Circulation. 116 (7): 803. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.185752.

- Eisenman A (2006). "Troponin assays for the diagnosis of myocardial infarction and acute coronary syndrome: where do we stand?". Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 4 (4): 509–14. doi:10.1586/14779072.4.4.509. PMID 16918269. S2CID 38481075.

- Aviles RJ, Askari AT, Lindahl B, Wallentin L, Jia G, Ohman EM, Mahaffey KW, Newby LK, Califf RM, Simoons ML, Topol EJ, Berger P, Lauer MS (2002). "Troponin T levels in patients with acute coronary syndromes, with or without renal dysfunction". N Engl J Med. 346 (26): 2047–52. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa013456. PMID 12087140.. Summary for laymen

- Apple FS, Wu AH, Mair J, et al. (2005). "Future biomarkers for detection of ischemia and risk stratification in acute coronary syndrome". Clin. Chem. 51 (5): 810–24. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2004.046292. PMID 15774573.

- Braunwald E, Antman EM, Beasley JW, Califf RM, Cheitlin MD, Hochman JS, Jones RH, Kereiakes D, Kupersmith J, Levin TN, Pepine CJ, Schaeffer JW, Smith EE III, Steward DE, Théroux P (2002). "ACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for the management of patients with unstable angina and non–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina)". J Am Coll Cardiol. 40 (7): 1366–74. doi:10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02336-7. PMID 12383588.

- Kolkailah (2018). "Radial artery versus femoral artery approach for performing coronary catheter procedures in people with coronary artery disease". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4: CD012318. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012318.pub2. PMC 6494633. PMID 29665617.

- Emanuel Rubin; Fred Gorstein; Raphael Rubin; Roland Schwarting; David Strayer (2001). Rubin's Pathology — Clinicopathological Foundations of Medicine. Maryland: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 546. ISBN 978-0-7817-4733-2.

- Eichbaum FW (1975). "'Wavy' myocardial fibers in spontaneous and experimental adrenergic cardiopathies". Cardiology. 60 (6): 358–65. doi:10.1159/000169735. PMID 782705.

- S Roy. Myocardial infarction. Retrieved November 28, 2006.

- Fishbein, M. C. (1990). "Reperfusion injury". Clinical Cardiology. 13 (3): 213–217. doi:10.1002/clc.4960130312. PMID 2182247. S2CID 23499085.

- Unless otherwise specified in boxes, reference is: Michaud, Katarzyna; Basso, Cristina; d'Amati, Giulia; Giordano, Carla; Kholová, Ivana; Preston, Stephen D.; Rizzo, Stefania; Sabatasso, Sara; Sheppard, Mary N.; Vink, Aryan; van der Wal, Allard C. (2019). "Diagnosis of myocardial infarction at autopsy: AECVP reappraisal in the light of the current clinical classification". Virchows Archiv. 476 (2): 179–194. doi:10.1007/s00428-019-02662-1. ISSN 0945-6317. PMC 7028821. PMID 31522288.

- "This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Archived 2015-11-21 at the Wayback Machine)"

- Chute, Michael; Aujla, Preetinder; Jana, Sayantan; Kassiri, Zamaneh (2019). "The Non-Fibrillar Side of Fibrosis: Contribution of the Basement Membrane, Proteoglycans, and Glycoproteins to Myocardial Fibrosis". Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease. 6 (4): 35. doi:10.3390/jcdd6040035. ISSN 2308-3425. PMC 6956278. PMID 31547598.

- Gräni, Christoph; Eichhorn, Christian; Bière, Loïc; Kaneko, Kyoichi; Murthy, Venkatesh L.; Agarwal, Vikram; Aghayev, Ayaz; Steigner, Michael; Blankstein, Ron; Jerosch-Herold, Michael; Kwong, Raymond Y. (2019). "Comparison of myocardial fibrosis quantification methods by cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging for risk stratification of patients with suspected myocarditis". Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. 21 (1): 14. doi:10.1186/s12968-019-0520-0. ISSN 1532-429X. PMC 6393997. PMID 30813942.

- Bhaskaran, Ashwin; Tung, Roderick; Stevenson, William G.; Kumar, Saurabh (2019). "Catheter Ablation of VT in Non-Ischaemic Cardiomyopathies: Endocardial, Epicardial and Intramural Approaches". Heart, Lung and Circulation. 28 (1): 84–101. doi:10.1016/j.hlc.2018.10.007. ISSN 1443-9506. PMID 30385114. S2CID 54349750.

- Bishop JE, Greenbaum R, Gibson DG, Yacoub M, Laurent GJ. Enhanced deposition of predominantly type I collagen in myocardial disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1990;22:1157–1165

- Table 11-2 in: Mitchell, Richard Sheppard; Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson (1997). Robbins Basic Pathology. Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 1-4160-2973-7. 8th edition.