1775–1782 North American smallpox epidemic

The New World of the Western Hemisphere was devastated by the 1775–1782 North American smallpox epidemic. Estimates based on remnant settelments say 30,000,000 people were estimated to have died in the epidemic that started in 1775.[1]

Background

Smallpox was a dangerous disease caused by the variola major virus. The most common type of smallpox, ordinary, historically has devastated populations with a 30% death rate. The smallpox virus is transmittable through bodily fluids and materials contaminated with infected materials. Generally, face-to-face contact is required for an individual to contract smallpox as a result of an interaction with another human. Unlike some viruses, humans are the only carriers of variola major. This limits the chances of the virus being unknowingly spread through contact with insect or other animal populations. Persons infected with smallpox are infectious to others for about 24 days after their infection time. However, there is a period of time in which individuals are contagious but have only begun to experience minor symptoms such as fever, headaches, body aches, and sometimes vomiting.[2]

This epidemic occurred during the years of the American Revolutionary War. During this time, there was no medical technology widely available to protect soldiers from outbreaks in crowded and unhygienic troop camps. Thus, this virus posed a major threat to the success of the Continental Army, led by George Washington.

It is not known where the outbreak began, but the epidemic was not limited to the colonies on the Eastern seaboard, nor to the areas ravaged by hostilities. The outbreak spread throughout the North American continent. In 1775 it was already raging through British-occupied Boston and among the Continental Army's invasion of Canada. During Washington's siege of Boston the disease broke out among both Continental and British camps. Many escaped slaves who had fled to the British lines in the South likewise contracted smallpox and died. In the South, it reached Texas, and from 1778 to 1779, New Orleans was especially hard hit due to its densely populated urban area. By 1779 the disease had spread to Mexico and would cause the deaths of tens of thousands. At its end the epidemic had crossed the Great Plains, reaching as far west as the Pacific coast, as far north as Alaska and as far south as Mexico, infecting virtually every part of the continent.

One of the worst tragedies of the pandemic was the massive toll it took on the indigenous population of the Americas. The disease was likely spread via the travels of the Shoshone Indian tribes. Beginning in 1780 it reached the Pueblos of the territory comprising present day New Mexico. It also showed up in the interior trading posts of the Hudson's Bay Company in 1782.[3][4] It affected nearly every tribe on the continent, including the northwestern coast. It is estimated to have killed nearly 11,000 Native Americans in the Western area of present-day Washington, reducing the population from 37,000 to 26,000 in just seven years.

Quarantine methods

Though there was not too much known about viruses and their transitions, English colonists in North America recognized the effectiveness of isolating individuals infected with smallpox. The English colonies were more aware of the features of smallpox than of almost any other infectious disease. It was widely recognized that there were only two options for protecting oneself against this disease, quarantine or inoculation against the disease. Many feared inoculation, and instead chose isolation via quarantine. Individuals with recognized infections were sent to remote locations where they could let the disease run its course without the fear of infecting others. If needed, the scale of the quarantine could be increased. This meant cutting off entire towns from the rest of the colonies for the duration of the disease.

Members of the English colonies as well as English officials were proactive in establishing quarantine guidelines in order to protect the public. One of the earliest recorded examples of this was a quarantine established in 1647 by Puritans in order to prevent the spread of disease from ships coming from the Caribbean. In 1731 an act, entitled "An Act to Prevent Persons From Concealing the Smallpox", was passed. This act made the heads of households mandatory reporters for smallpox; these individuals were required to report smallpox in their house to the selectmen of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Infected households would then be indicated with the placement of a red flag.[5] In South Carolina, sentinels were to be posted outside infected households and infectious notices were required to be posted. In many colonies islands were set up to quarantine individuals coming in by ship. This decreased the chances of smallpox being introduced via trade or travel. By the late 1700s, almost all colonies had quarantine laws in effect in order to diminish the hugely damaging effects that smallpox could have on their communities.[6]

Upon taking charge of the Continental Army, Washington recognized the severe danger that smallpox posed to his men and the outcome of the war. To this end, Washington became "particularly attentive to the least Symptoms of Smallpox" [7] among his men. Further, Washington was prepared to quarantine any member of his troops showing symptoms according to previously discovered methods and guidelines, including through the use of a special hospital. Following an outbreak of smallpox in Boston, Washington took further precautions to protect his men; he quarantined his men from the dangerous Boston public. These measures included the refusal to allow contact between his soldiers and the viral refugees of Boston. Additionally, certain retreats of the Continental Army can be linked to Washington's wish to avoid smallpox and his intense caution when it came to his troops.[7]

Inoculation

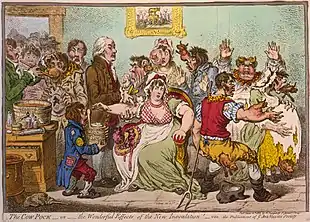

Though it was practiced in many parts of the world, the technology of inoculation, or variolation, was not in use in Europe apart from Wales, where it was reportedly in use as early as 1600.[8] The practice was widely publicized over a century later by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, who inoculated her own children against smallpox, despite widespread concern and controversy. Inoculation was the practice of introducing infected materials into the bodies of healthy individuals with the hope that they would contract a mild form of smallpox, recover, and be immune to further infections. The outcome of inoculations in surviving patients was successful. These individuals proved to be immune to smallpox. Understandably, there was much concern surrounding the practice of inoculation. The ordinary person was unable to comprehend the efficacy of intentionally infecting an otherwise healthy person with a potentially fatal disease. Thus, many were reluctant to have themselves or their family members inoculated. There were instances in which these fears were validated. Many of those who had been inoculated died as a result of the smallpox they had been exposed to. Additionally, there was the potential for an accidental outbreak of smallpox after contact between inoculation patients and the public. The choice of significant individuals such as John Adams and Abigail Adams to be inoculated did some to make inoculations more accepted, but there was still much progress to be made.

George Washington

George Washington contributed greatly to the progression of public health systems in America. During his time working with the Continental Army, Washington observed how smallpox and other diseases spread like wildfire through Army camps and gatherings. This was often due to the cramped and dirty living conditions of these places. Washington understood the destructive nature of smallpox and other diseases such as malaria, diphtheria, and scarlet fever. He was one of the first to introduce the idea of compulsory health initiatives such as widespread inoculation. Washington also had experience with disease outside the realm of combat and war. Having himself suffered from many illnesses and observing those of his family, George Washington was an integral part of the establishment of American public health programs.[9]

Along with quarantine, another one of Washington's methods for keeping his men healthy was with the use of inoculation. Washington, like others of the time period, was not intimately familiar with the exact mechanisms of the virus. However, he and others were able to realize that men who had previously contracted and subsequently recovered from smallpox were unlikely to become ill a second time. Thus, early on Washington recognized the strategic advantage of these individuals. During an outbreak in Boston, Washington sent troops made up only of men who had previously been infected with smallpox. With this, he was able to both protect his soldiers and take advantage of the vulnerability of Boston and its British inhabitants during the smallpox outbreak of March 1776.[7]

Initially, George Washington was reluctant to inoculate his troops. But as he watched many of his men fall victim to smallpox, Washington believed that he would be able to keep his troops healthy through sanitary and quarantine methods. There were several events that contributed to the change of Washington's policy. First, Washington recognized that quarantine and attempted cleanliness were not enough to keep his vital troops healthy and in fighting form. Additionally, many prominent members of colonial society were having themselves and their families inoculated. Eventually, even George Washington's wife, Martha Washington was herself inoculated. It was not long after this that Washington initiated the inoculation of the American troops. Washington recognized the dangers of inoculating these men; many patients died as result of the infection caused by inoculation. However, the importance of keeping his men healthy outweighed the risks, and almost all Continental soldiers were inoculated against smallpox.[10] Washington (a survivor of smallpox himself) understood the danger that smallpox posed to his men, saying "Necessity not only authorizes but seems to require the measure, for should the disorder infect the Army . . . we should have more to dread from it, than from the Sword of the Enemy."[11] However, it was more complex than just Washington making this decision. Local officials were concerned that the inoculation of soldiers would lead to the accidental spread of smallpox among civilians. But Washington persisted in his quest and managed to get the majority of his soldiers inoculated. Along with the rise in popularity of the practice, Washington's decision to inoculate his troops was also extremely strategic; he was able to realize the deep impact an epidemic would have on his troops. Immunity was initially more widespread among the British men than the Americans. This was due to the more accepted practice of inoculation in Europe and the high rate of childhood cases, resulting in immunity. With this, an epidemic spread among Americans could prove disastrous to the American cause. With his men at Valley Forge inoculated, Washington was able to proceed with more confidence, knowing that at least his men would not be struck down by the smallpox virus.[12]

John and Abigail Adams

Both John and Abigail Adams were intimately familiar with disease and illness, having seen many family members and themselves infected. Thus, Abigail made certain to educate her children on the dangers of disease and how to best avoid it. These lessons included both practices of cleaning and the administration of home medicine. The Adams both understood the toll that smallpox could take and therefore feared the disease and its potentially devastating lasting effects. In July 1764, John Adams set an example by choosing to be inoculated before it was a commonly accepted practice. Though techniques were rudimentary at this time, Adams survived the experience, emerging with protective immunity. Adams described the inoculation procedure in a letter to his wife:

- "Dr. Perkins demanded my left arm and Dr. Warren my brother's [probably Peter Boylston Adams]. They took their Launcetts and with their Points divided the skin about a Quarter of an inch and just suffering the blood to appear, buried a thread (infected) about a Quarter of an inch long in the Channell. A little lint was then laid over the scratch and a Piece of Ragg pressed on, and then a Bandage bound over all, and I was bid go where and do what I pleased...Do not conclude from any Thing I have written that I think Inoculation a light matter -- A long and total abstinence from everything in Nature that has any Taste; two long heavy Vomits, one heavy Cathartick, four and twenty Mercurial and Antimonial Pills, and, Three weeks of Close Confinement to an House, are, according to my Estimation, no small matters."[13]

With this act, John Adams set a precedent for many. At the time of his inoculation, the practice was still highly controversial and distrusted by most. This stemmed from the cases in which inoculation patients died as a result of the contracted disease. Additionally, there was always the risk of inoculation patients unintentionally infecting others. However, Adams understood that the benefits of inoculation far outweighed the potential risks. Having a background in medicine, Adams strove to educate others on his findings and beliefs. John Adams was certainly a leading figure in the American Revolution; he played many important roles and was known to many. Adams was able to spread his progressive beliefs about public health programs such as inoculation by taking advantage of his status during this time.[9]

In July 1776, Abigail and their four children, Charles, Nabby, Thomas, and John Quincy, were all inoculated.[14]

Implications for public health

Many of the leading figures associated with the American Revolution were also involved in the attempt to stop the disastrous spread of smallpox throughout the American Colonies and beyond. Such individuals included George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin, among others. Prior to the steps made by these parties, public health policies in the colonies were not well established; they were limited to emergency situations. This is to say that policies and programs sprung up around epidemics and quarantines, wherever they were needed in the moment.[9] However, the scourge of smallpox prompted changes to be made that would impact the public health of America for years to come.

At the time of its introduction, almost all colonists were extremely wary of this new medical procedure. It was difficult for them to understand how the infection of an otherwise healthy individual could have a positive outcome. However, inoculation saved many lives and may have protected the Continental Army from destruction. The smallpox inoculation program paved the way for the global public health system that is responsible for the control and eradication of many deadly diseases, including but not limited to polio, measles, and diphtheria.

References

- Yardley, Jonathan (October 25, 2001). "The forgotten epidemic". Washington Post. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- "Smallpox Overview". 2016.

- Mackenzie, Alexander (1801), Voyages from Montreal, London: Printed for T. Cadell, Jun. and W. Davies ..., Cobbett and Morgan ..., and W. Creech, at Edinburgh, by R. Noble ..., ISBN 066533950X, 066533950X

- Fenn, Elizabeth A., History Today (The Great Smallpox Epidemic), retrieved 2014-08-02

- Principles and Practice of Public Health Surveillance. 2010.

- Pox Americana. 2001.

- "Smallpox".

- Boylston, Arthur (July 2012). "The origins of inoculation". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 105 (7): 309–313. doi:10.1258/jrsm.2012.12k044. PMC 3407399. PMID 22843649.

- Revolutionary Medicine:The Founding Fathers and Mothers in Sickness and in Health. 2013.

- Revolutionary Medicine: The Founding Fathers and Mothers in Sickness and in Health. 2013.

- "George Washington and the First Mass Military Inoculation". 2009.

- "Smallpox in Washington's Army: Strategic Implications of the Disease During the American Revolutionary War". 2004.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Blinderman, A. "John Adams: fears, depressions, and ailments." NY State J Med. 1977;77:268-276."

- Bumgarner, John R. The Health of the Presidents: The 41 United States Presidents Through 1993 from a Physician's Point of View. Jefferson, NC: MacFarland & Company, 1994; pp. 9-10.

Further reading

- Abrams, Jeanne E. (2013). Revolutionary Medicine: The Founding Fathers and Mothers in Sickness and in Health. New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-8919-3.

- Becker, Ann M. (2004). "Smallpox in Washington's Army: Strategic Implications of the Disease During the American Revolutionary War". The Journal of Military History. 68 (2): 381–430. doi:10.1353/jmh.2004.0012. S2CID 159630679.

- Carlos, Ann M.; Lewis, Frank D. (2012). "Smallpox and Native American mortality: The 1780s epidemic in the Hudson Bay region". Explorations in Economic History. 49 (3): 277–290. doi:10.1016/j.eeh.2012.04.003.

- Coss, Stephen (2016). The Fever of 1721: The Epidemic that Revolutionized Medicine and American Politics. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4767-8308-6.

- Fenn, Elizabeth A. (2001). Pox Americana: The Great Smallpox Epidemic of 1775–82. Hill and Wang. ISBN 0-8090-7821-X.

- Filsinger, Amy Lynn; Dwek, Raymond (2009). "George Washington and the First Mass Military Inoculation". Library of Congress Science Reference Services.

- McIntyre, John W.R.; H (December 1999). "Smallpox and its control in Canada". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 161 (12): 1543–7. PMC 1230874. PMID 10624414.

- Savas, Theodore P.; Dameron, J. David (January 2010). New American Revolution Handbook. New York, NY: Savas Beatie. ISBN 978-1-932714-93-7.