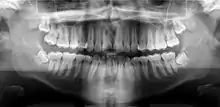

Panoramic radiograph

A panoramic radiograph is a panoramic scanning dental X-ray of the upper and lower jaw. It shows a two-dimensional view of a half-circle from ear to ear. Panoramic radiography is a form of focal plane tomography; thus, images of multiple planes are taken to make up the composite panoramic image, where the maxilla and mandible are in the focal trough and the structures that are superficial and deep to the trough are blurred.

| Panoramic radiograph | |

|---|---|

A dental panoramic radiograph, showing the maxilla and mandible, all the teeth including the "wisdom teeth," the frontal and maxillary sinuses, the nasal cavity and the temporomandibular joint and other near by head and neck anatomy. | |

| MeSH | D011862 |

Other nonproprietary names for a panoramic radiograph are dental panoramic radiograph and pantomogram; Abbreviations include PAN, DPR, OPT, and OPG (the latter, based on genericizing a trade name, are often avoided in medical editing).

Types

Dental panoramic radiography equipment consists of a horizontal rotating arm which holds an X-ray source and a moving film mechanism (carrying a film) arranged at opposed extremities. The patient's skull sits between the X-ray generator and the film. The X-ray source is rectangular collimated beam.[1] Also the height of that beam covers the mandibles and the maxilla regions. The arm moves and its movement may be described as a rotation around an instant center which shifts on a dedicated trajectory.

The manufacturers propose different solutions for moving the arm, trying to maintain constant distance between the teeth to the film and generator. Also those moving solutions try to project the teeth arch as orthogonally as possible. It is impossible to select an ideal movement as the anatomy varies very much from person to person. Finally a compromise is selected by each manufacturer and results in magnification factors which vary strongly along the film (15%-30%). The patient positioning is very critical in regard to both sharpness and distortions.

Films

There are two kinds of film moving mechanisms, one using a sliding flat cassette which holds the film, and another using a rotating cylinder around which the film is wound. There are two standard sizes for dental panoramic films: 30 cm × 12 cm (12″ × 5″) and 30 cm x 15 cm (12″ × 6″). The smaller size film receives 8% less X-ray dosage on it compared to the bigger size.

Digital

Dental X-rays' radiology is moving from film technology (involving a chemical developing process) to digital X-ray technology, which is based on electronic sensors and computers. One of the principal advantages compared to film based systems is the much greater exposure latitude. This means many fewer repeated scans, which reduces costs and also reduces patient exposure to radiation. Lost X-rays can also be reprinted if the digital file is saved. Other significant advantages include instantly viewable images, the ability to enhance images, the ability to email images to practitioners and clients (without needing to digitize them first), easy and reliable document handling, reduced X-ray exposure, that no darkroom is required, and that no chemicals are used.

One particular type of digital system uses a photostimulable phosphor plate (aka PSP - Phosphor Plate) in place of the film. After X-ray exposure the plate (sheet) is placed in a special scanner where the latent formed image is retrieved point by point and digitized, using a laser light scanning. The digitized images are stored and displayed on the computer screen. This method is in between old film based technology and the current direct digital imaging technology. It is similar to the film process because it involves the same image support handling and differs because the chemical development process is replaced by the scanning process. This is not much faster than film processing and the resolution and sensitivity performances are contested. However it has the clear advantage of being able to fit with any existing equipment without any modification because it replaces just the existing film.

Also sometimes the term "digital X-rays" is used to designate the scanned film documents which further are handled by computers.

The other types of digital imaging technologies use electronic sensors. A majority of them first convert the X-rays in light (using a GdO2S or CsI layer) which is further captured using a CCD or a CMOS image sensor. Few of them use a hybrid analog-to-digital arrangement which first converts the X-ray into electricity (using a CdTe layer) and then this electricity is rendered as an image by a reading section based on CMOS technology.

In current state-of-the-art digital systems, the image quality is vastly superior to conventional film-based systems. The latest advancements have also seen the addition on Cone Beam 3D Technology to standard digital panoramic devices.

Indications

.jpg.webp)

Orthopantomograms (OPTs) are used by health care professionals to provide information on:

- Impacted wisdom teeth diagnosis and treatment planning - the most common use is to determine the status of wisdom teeth and trauma to the jaws.

- Periodontal bone loss and periapical involvement.

- Finding the source of dental pain, and when carrying out tooth-by-tooth diagnosis.

- Assessment for the placement of dental implants

- Orthodontic assessment. pre and post operative

- Diagnosis of developmental anomalies such as cherubism, cleido cranial dysplasia

- Carcinoma in relation to the jaws

- Temporomandibular joint dysfunctions and ankylosis.

- Diagnosis of osteosarcoma, ameloblastoma, renal osteodystrophy affecting jaws and hypophosphatemia.

- Diagnosis, and pre- and post-surgical assessment of oral and maxillofacial trauma, e.g. dentoalveolar fractures and mandibular fractures.

- Salivary stones (Sialolithiasis).

- Other diagnostic and treatment applications.[2]

Mechanism

Normally, the person bites on a plastic spatula so that all the teeth, especially the crowns, can be viewed individually. The whole orthopantomogram process takes about one minute. The patient's actual radiation exposure time varies between 5.5 and 22 seconds for the machine’s excursion around the skull.

The collimation of the machine means that, while rotating, the X-rays project only a limited portion of the anatomy onto the film at any given instant but, as the rotation progresses around the skull, a composite picture of the maxillo-facial block is created. While the arm rotates, the film moves in a such way that the projected partial skull image (limited by the beam section) scrolls over it and exposes it entirely. Not all of the overlapping individual images projected on the film have the same magnification because the beam is divergent and the images have differing focus points. Also not all the element images move with the same velocity on the target film as some of them are more distant from and others closer to the instant rotation center. The velocity of the film is controlled in such fashion to fit exactly the velocity of projection of the anatomical elements of the dental arch side which is closest to the film. Therefore, they are recorded sharply while the elements in different places are recorded blurred as they scroll at different velocity.

The dental panoramic image suffers from important distortions because a vertical zoom and a horizontal zoom both vary differently along the image. The vertical and horizontal zooms are determined by the relative position of the recorded element versus film and generator. Features closer to the generator receive more vertical zoom. The horizontal zoom is also dependent on the relative position of the element to the focal path. Features inside the focal path arch receive more horizontal zoom and are blurred; features outside receive less horizontal zoom and are blurred.

The result is an image showing sharply the section along the mandible arch, and blurred elsewhere. For example, the more radio-opaque anatomical region, the cervical vertebrae (neck), shows as a wide and blurred vertical pillar overlapping the front teeth. The path where the anatomical elements are recorded sharply is called "focal path".

Principal advantage of panoramic images

- Broad coverage of facial bone and teeth

- Low patient radiation dose

- Convenience of examination for the patient (films need not be placed inside the mouth)

- Ability to be used in patients who cannot open the mouth or when the opening is restricted e.g.: due to trismus

- Short time required for making the image

- Patient's ready understandability of panoramic films, making them a useful visual aid in patient education and case presentation.

- Easy to store compared to the large set of intra oral x-rays which are typically used.[3]

Preparation

Persons who are to undergo panoramic radiography usually are required to remove any earrings, jewellery, hair pins, glasses, dentures or orthodontic appliances.[4] If these articles are not removed, they may create artifacts on the image (especially if they contain metal) and reduce its usefulness. There is also a need for the person to stay absolutely still during the 18 or so second cycle it takes for the machine to expose the film. For this reason, radiographers often explain to the person beforehand how the machine will move.[4]

Adverse effects

Like any medical imaging utilizing ionizing radiation, there will be a minute degree of direct ionizing damage and indirect damage from free radicals created during the ionization of water molecules within cells. A rough estimate of the risk of fatal cancer from a panoramic radiograph is about 1 in 20,000,000.[4] The age of the person being imaged also alters the risk, with younger people having a slightly higher risk. E.g. the 1 in 20,000,000 risk would be doubled for someone in the 1-10 age group (1 in 10,000,000).[4]

History

Historical milestones for digital panoramic systems

1985–1991 – The first attempt to build a dental digital panoramic was of McDavid et al. at UTHSCSA.[5] Their idea was based on a linear pixel array(single pixel column) sensor which was not appropriate for such an application because: a) there is no tomographic effect; b) huge difficulties to collimate the X-rays beam and to control the X-ray dose delivered to the patient; c) poor generator efficiency.

1995 – DXIS, the first dental digital panoramic X-rays system available on the market, created by Catalin Stoichita at Signet (France). DXIS targeted to retrofit all the panoramic models.

1997 – SIDEXIS, of Siemens (currently Sirona Dental Systems, Germany) offered a digital option for Ortophos Plus panoramic unit, DigiPan of Trophy Radiology (France) offered a digital option for the OP100 panoramic made by Instrumentarium (Finland).

1998–2004 – many panoramic manufacturers offered their own digital systems.

Research

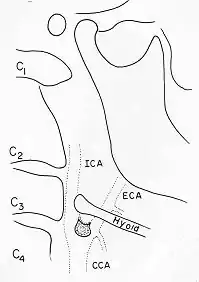

Panoramic radiographs have the capability to demonstrate a portion of the neck and display atheromas (calcifications in the carotid artery) which are an indication of both local and generalized (systemic) atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis of the coronary arteries leading to myocardial infarction (heart attack), and atherosclerosis of the carotid artery leading to stroke are the number one and number three most common causes of death in the United States.[6]

There is interest to look at panoramic radiographs as a screening tool, however further data is needed with regards if it is able to make a meaningful difference in outcomes.[7]

Epidemiology: general public and high risk groups

Additional research projects have further determined the prevalence rate of these atheromas in the general population (3–5%)[8][9] and among high-risk groups (over 25% in: recent stroke victims,[10] individuals with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome,[11][12][13] postmenopausal women,[14] type 2 diabetics,[15][13][16] individuals with dilated cardiomyopathy,[17][13] and among individuals who have received radiotherapy directed at the neck,[18][19]). These findings have been corroborated by other several other researchers.[20][21][22][23][13]

Dental infection and atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis is attributed to risk factors that include cigarette smoking, hyperlipidemia, obesity, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension (high blood pressure). These factors, however, do not fully account for the risk of disease. Atherosclerosis has been conceptualized as a chronic inflammatory response to endothelial cell injury[24] and dysfunction possibly arising from chronic dental infection. In 2010, using the previously validated Mattila panoramic radiographic index to quantify the totality of dental infection (i.e., periapical and furcal lesions, pericoronitis sites, carious tooth roots, teeth with pulpal caries, and vertical bony defects), Friedlander’s group determined that individuals with carotid artery atheromas on their panoramic radiographs had significantly greater amounts of dental infection/inflammation than atherogenic risk-matched controls devoid of radiographic atheromas.[25][26] While the Mattila index had been previously used to relate the extent of dental infection to coronary artery disease, this research is the first to link the full range of dental disease that it measures to panoramic radiographs evidencing calcified carotid artery atherosclerosis.

References

- Langlais, Robert. "RECTANGULAR COLLIMATION No longer a matter of choice!".

- Dental Radiographic Examinations: Recommendations For Patient Selection And Limiting Radiation Exposure. Am Dent Assoc, U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services, FDA. Revised: 2012

- Stuart C. White, Micheal J Pharoh, Oral Radiology and Interpretation Mosby 2005

- Whaites E, (foreword by Cawson RA) (2007). Essentials of dental radiography and radiology (4th ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 187–206. ISBN 978-0-443-10168-7.

- "Apparatus and method for producing digital panoramic x-ray images".

- American Heart Association’s Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2010 Update

- Roldán-Chicano, R; Oñate-Sánchez, RE; López-Castaño, F; Cabrerizo-Merino, MC; Martínez-López, F (May 1, 2006). "Panoramic radiograph as a method for detecting calcified atheroma plaques. Review of literature". Medicina Oral, Patologia Oral y Cirugia Bucal. 11 (3): E261–6. PMID 16648765.

- Friedlander, AH; Garrett, NR; Chin, EE; Baker, JD (2005). "Ultrasonographic confirmation of carotid artery atheromas diagnosed via panoramic radiography". Journal of the American Dental Association. 136 (5): 635–40. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2005.0235. PMID 15966651. Archived from the original on 2010-06-23. Retrieved 2010-12-30.

- Almog, DM; Illig, KA; Carter, LC; Friedlander, AH; Brooks, SL; Grimes, RM (November 2004). "Diagnosis of non-dental conditions. Carotid artery calcifications on panoramic radiographs identify patients at risk for stroke". The New York State Dental Journal. 70 (8): 20–5. PMID 15615333.

- Friedlander, AH; Manesh, F; Wasterlain, CG (1994). "Prevalence of detectable carotid artery calcifications on panoramic radiographs of recent stroke victims". Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, and Oral Pathology. 77 (6): 669–73. doi:10.1016/0030-4220(94)90332-8. PMID 8065736.

- Friedlander, AH; Yueh, R; Littner, MR (1998). "The prevalence of calcified carotid artery atheromas in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome". Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 56 (8): 950–4. doi:10.1016/s0278-2391(98)90657-7. PMID 9710189.

- Friedlander, AH; Friedlander, IK; Yueh, R; Littner, MR (1999). "The prevalence of carotid atheromas seen on panoramic radiographs of patients with obstructive sleep apnea and their relation to risk factors for atherosclerosis". Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 57 (5): 516–21, discussion 521–2. doi:10.1016/s0278-2391(99)90065-4. PMID 10319824.

- Alves, N; Deana, NF; Garay, I (2014). "Detection of common carotid artery calcifications on panoramic radiographs: prevalence and reliability". International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine. 7 (8): 1931–9. PMC 4161533. PMID 25232373.

- Friedlander, AH; Altman, L (2001). "Carotid artery atheromas in postmenopausal women. Their prevalence on panoramic radiographs and their relationship to atherogenic risk factors". Journal of the American Dental Association. 132 (8): 1130–6. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0340. PMID 11575022. Archived from the original on 2009-05-23. Retrieved 2010-12-30.

- Friedlander, AH; Garrett, NR; Norman, DC (2002). "The prevalence of calcified carotid artery atheromas on the panoramic radiographs of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus". Journal of the American Dental Association. 133 (11): 1516–23. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2002.0083. PMID 12462696. Archived from the original on 2008-09-08. Retrieved 2010-12-30.

- Friedlander, AH; Maeder, LA (2000). "The prevalence of calcified carotid artery atheromas on the panoramic radiographs of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus". Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontics. 89 (4): 420–4. doi:10.1016/S1079-2104(00)70122-3. PMID 10760724.

- Sung, EC; Friedlander, AH; Kobashigawa, JA (2004). "The prevalence of calcified carotid atheromas on the panoramic radiographs of patients with dilated cardiomyopathy". Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontics. 97 (3): 404–7. doi:10.1016/j.tripleo.2003.08.025. PMID 15024368.

- Friedlander, AH; Eichstaedt, RM; Friedlander, IK; Lambert, PM (1998). "Detection of radiation-induced, accelerated atherosclerosis in patients with osteoradionecrosis by panoramic radiography". Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 56 (4): 455–9. doi:10.1016/s0278-2391(98)90712-1. PMID 9541345.

- Friedlander, AH; August, M (1998). "The role of panoramic radiography in determining an increased risk of cervical atheromas in patients treated with therapeutic irradiation". Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontics. 85 (3): 339–44. doi:10.1016/S1079-2104(98)90020-8. PMID 9540095.

- Carter, LC; Haller, AD; Nadarajah, V; Calamel, AD; Aguirre, A (1997). "Use of panoramic radiography among an ambulatory dental population to detect patients at risk of stroke". Journal of the American Dental Association. 128 (7): 977–84. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.1997.0338. PMID 9231602. Archived from the original on 2008-11-23. Retrieved 2010-12-30.

- Lewis, DA; Brooks, SL (1999). "Cartoid artery calcification in a general dental population: a retrospective study of panoramic radiographs". General Dentistry. 47 (1): 98–103. PMID 10321159.

- Almog, DM; Illig, KA; Khin, M; Green, RM (2000). "Unrecognized carotid artery stenosis discovered by calcifications on a panoramic radiograph". Journal of the American Dental Association. 131 (11): 1593–7. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2000.0088. PMID 11103578. Archived from the original on 2009-05-23. Retrieved 2010-12-30.

- Farman, AG; Farman, TT; Khan, Z; Chen, Z; Carter, LC; Friedlander, AH (2001). "The role of the dentist in detection of carotid atherosclerosis". South African Dental Journal. 56 (11): 549–53. PMID 11885436.

- Epstein, Franklin H.; Ross, Russell (1999). "Atherosclerosis — an Inflammatory Disease". New England Journal of Medicine. 340 (2): 115–26. doi:10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. PMID 9887164.

- Mattila, KJ; Nieminen, MS; Valtonen, VV; Rasi, VP; Kesäniemi, YA; Syrjälä, SL; Jungell, PS; Isoluoma, M; et al. (25 March 1989). "Association between dental health and acute myocardial infarction". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 298 (6676): 779–81. doi:10.1136/bmj.298.6676.779. PMC 1836063. PMID 2496855.

- Friedlander, AH; Sung, EC; Chung, EM; Garrett, NR (2010). "Radiographic quantification of chronic dental infection and its relationship to the atherosclerotic process in the carotid arteries". Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontics. 109 (4): 615–21. doi:10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.10.036. PMID 20097109.