Pacifier

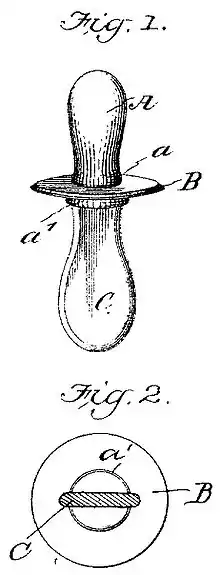

A pacifier is a rubber, plastic, or silicone nipple substitute given to an infant to suckle upon between feedings to quiet its distress by satisfying the need to suck when it does not need to eat. Pacifiers normally have three parts, an elongated teat, a mouth shield, and a handle. The mouth shield is large enough to prevent the child from attempting to take the pacifier into its mouth, and so forecloses the danger that the child will swallow then choke on it.

Pacifiers have many different informal names: binky or wookie (American English), dummy (Australian English and British English), soother (Canadian English and Hiberno-English[1]), and Dodie (Hiberno-English[2]).

History

Pacifiers were mentioned for the first time in medical literature in 1473, being described by German physician Bartholomäus Metlinger in his book Kinderbüchlein, in later editions retitled Regiment der jungen Kinder ("Caring For Young Children").

In England in the 17th–19th centuries, a coral was a teething toy made of coral, ivory or bone, often mounted in silver as the handle of a rattle.[3] A museum curator has suggested that these substances were used as "sympathetic magic"[4] and that the animal bone could symbolize animal strength to help the child cope with pain.

Pacifiers were a development of hard teething rings, but they were also a substitute for the softer sugar tits, sugar-teats or sugar-rags[5] which had been in use in 19th century America. A writer in 1873 described a "sugar-teat" made from "a small piece of old linen" with a "spoonful of rather sandy sugar in the center of it", "gathered ... up into a little ball" with a thread tied tightly around it.[6] Rags with foodstuffs tied inside were also given to babies in many parts of Northern Europe and elsewhere. In some places a lump of meat or fat was tied in cloth, and sometimes the rag was moistened with brandy. German-speaking areas might use Lutschbeutel, cloth wrapped around sweetened bread or poppy-seeds.

A Madonna and child painted by Dürer in 1506[7] shows one of these tied-cloth "pacifiers" in the baby's hand.

Pacifiers were settling into their modern form around 1900 when the first teat, shield and handle design was patented in the US as a "baby comforter" by Manhattan pharmacist Christian W. Meinecke.[8] Rubber had been used in flexible teethers sold as "elastic gum rings" for British babies in the mid-19th century,[9] and also used for feeding-bottle teats. In 1902, Sears, Roebuck & Co. advertised a "new style rubber teething ring, with one hard and one soft nipple".[9] And in 1909 someone calling herself "Auntie Pacifier" wrote to the New York Times to warn of the "menace to health" (she meant dental health) of "the persistent, and, among poorer classes, the universal sucking of a rubber nipple sold as a 'pacifier'."[10] In England too, dummies were seen as something the poorer classes would use, and associated with poor hygiene. In 1914 a London doctor complained about "the dummy teat": "If it falls on the floor it is rubbed momentarily on the mother's blouse or apron, lipped by the mother and replaced in the baby's mouth."[11]

Early pacifiers were manufactured with a choice of black, maroon or white rubber, though the white rubber of the day contained a certain amount of lead. Binky (with a y) was first used in about 1935 as a trademarked brand name for pacifiers and other baby products manufactured by the Binky Baby Products Company of New York. The brand name is currently owned by Playtex Products, LLC as a trademark in the U.S. (and a number of other countries).[12]

Drawbacks

There are negative effects from using a pacifier during breastfeeding for healthy babies. The AAP suggests avoiding pacifiers for the first month. Introducing a pacifier can lead to the infant ineffectively sucking at the breast and causing "nipple confusion". Babies will take their suck out on the pacifier instead of nursing or comfort nursing at the breast which is good for the mother's supply. Evidence in premature infants or infants that are not healthy is lacking but shows that it can have benefits.[13] It may have clinical benefits for preterm babies, such as helping them progress from tube to bottle feeding.[14]

Infants who use pacifiers may have more ear infections (otitis media).[15] The effectiveness of avoiding the use of a pacifier to prevent ear infections is not known.[16]

Although it is commonly believed that using a pacifier will lead to dental problems, it does not appear to lead to long-term damage if used for less than around three years.[15] However, prolonged use of a pacifier or other non-nutritive sucking habit (such as finger or blanket sucking) has been found to lead to malocclusion of the teeth, that is teeth sticking out or not meeting properly when they bite together.[17][18] This is a common problem and the dental (orthodontic) treatment to correct it can take a long time and can be expensive. A Cochrane Review of the evidence found that orthodontic braces or psychological intervention (such as positive or negative reinforcement) were effective in helping children stop sucking habits where that was necessary.[19] An orthodontic brace that used a palatal crib design seems to have been more effective than a palatal arch design.

There appears to be no strong evidence that using a pacifier delays speech development by preventing babies from practicing their speaking skills.[15]

Benefits

Researchers have found that use of a pacifier is associated with a substantial reduction in the risk of sudden infant death syndrome.[20][21] They are divided over whether this association is sufficient reason to prefer pacifier use. Some argue that pacifiers should be recommended on the strength of an association, just as back sleeping was recommended on the strength of an association.[22][23] Others argue that the association is not strong enough or that the mechanism is unclear.[24]

Pacifiers have also been found to reduce infants' crying during painful procedures such as venipuncture.[25][26]

Some parents prefer the use of a pacifier to the child sucking their thumb or fingers.

Researchers in Brazil have shown that neither "orthodontic" nor standard pacifiers prevent dental problems if children continue sucking past the age of three years.[27]

It is commonly reported anecdotally that pacifier use among stimulant users helps reduce bruxism and thus prevents tooth damage. It is also known to help infants to get to sleep and also keeps infants calm.

Medical policies

The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry's "Policy on Thumb, Finger and Pacifier Habits" says: "Most children stop sucking on thumbs, pacifiers or other objects on their own between 2 and 4 years of age. However, some children continue these habits over long periods of time. In these children, the upper front teeth may tip toward the lip or not come in properly. Frequent or intense habits over a prolonged period of time can affect the way the child's teeth bite together, as well as the growth of the jaws and bones that support the teeth."[28]

A study of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) states that "It seems appropriate to stop discouraging the use of pacifiers." The authors recommend the use of pacifiers at nap time and bedtime throughout the first year of life. For breastfeeding mothers, the authors suggest waiting until breastfeeding is well established, typically for several weeks, before introducing the pacifier.[29]

The British Dental Health Foundation recommends: "If you can, avoid using a dummy and discourage thumb sucking. With prolonged use (see Drawbacks above), these can both eventually cause problems with how the teeth grow and develop. And this may need treatment with a brace when the child gets older."[30]

Prevalence of attachments to pacifiers and their psychological functions

In the late 1970s researchers dispelled the notion that pacifiers were psychologically unhealthy and aberrant. Richard H. Passman and Jane S. Halonen at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee traced the developmental course of attachments to pacifiers and provided norms.[31] They found that 66% of their sample of babies who were three months old in the United States demonstrated at least some attachment, according to their mothers. At six months of age, this incidence was 40%, and at nine months it was 44%. Thereafter, the rate of attachment to pacifiers dropped precipitously until, at 24 months of age and later, it was quite rare.

These researchers also provided experimental support for what were then only anecdotal observations that pacifiers do indeed pacify babies.[32] In an unfamiliar playroom, one-year-old infants accompanied by their pacifier evidenced more play and demonstrated less distress than did babies without them. The investigators concluded that pacifiers should be considered to be attachment objects, similar to other security objects like blankets.

Passman and Halonen[31] contended that the widespread occurrence of attachments to pacifiers as well as their importance as security objects should reassure parents that they are a normal part of development for a majority of infants.

See also

- Pacifier-activated lullaby

- Security blanket

References

- "Soothers. Discover the full range | Philips".

- "6 tips to get rid of the soother once and for all | HerFamily.ie".

- OED; Examples from the Metropolitan

- Victoria & Albert Museum of Childhood. Vam.ac.uk. Retrieved on 2013-04-14.

- Oxford English Dictionary

- Jamieson, Cecilia Viets (1873) Ropes of Sand. Chapter 2: Top's baby. Letrs.indiana.edu. Retrieved on 2013-04-14.

- Madonna and Siskin. Wga.hu. Retrieved on 2013-04-14.

- Design Patent number D33,212 C.W.Meinecke Sep 18 1900

- The history of the feeding bottle. babybottle-museum.co.uk

- Auntie Pacifier (July 2, 1909) The "Pacifier" a Menace to Health. New York Times.

- ''British Journal of Nursing: The Midwife'' Aug 7 1915. (PDF) . Retrieved on 2013-04-14.

- According to trademark registration documents 1948. Uspto.gov. Retrieved on 2013-04-14.

- Jaafar, Sharifah Halimah; Ho, Jacqueline J.; Jahanfar, Shayesteh; Angolkar, Mubashir (2016-08-30). "Effect of restricted pacifier use in breastfeeding term infants for increasing duration of breastfeeding". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (8): CD007202. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007202.pub4. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 8520760. PMID 27572944.

- Foster, Jann P.; Psaila, Kim; Patterson, Tiffany (2016-10-04). "Non-nutritive sucking for increasing physiologic stability and nutrition in preterm infants". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10 (3): CD001071. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001071.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6458048. PMID 27699765.

- Nelson, AM (December 2012). "A comprehensive review of evidence and current recommendations related to pacifier usage". Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 27 (6): 690–9. doi:10.1016/j.pedn.2012.01.004. PMID 22342261.

- Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health (IQWiG). "Middle ear infections: prevention". Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health (IQWiG). Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- Vázquez-Nava F, Quezada-Castillo JA, Oviedo-Treviño S, et al. (2006). "Association between allergic rhinitis, bottle feeding, non‐nutritive sucking habits, and malocclusion in the primary dentition". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 91 (10): 836–840. doi:10.1136/adc.2005.088484. PMC 2066013. PMID 16769710.

- Paroo Mistry; Moles David R; O'Neill Julian; Noar Joseph (2010). "The occlusal effects of digit sucking habits amongst school children in Northamptonshire (UK)". Journal of Orthodontics. 37 (2): 87–92. doi:10.1179/14653121042939. PMID 20567031. S2CID 5519168.

- Borrie FRP, Bearn DR, Innes NPT, Iheozor-Ejiofor Z (2015). "Interventions for the cessation of non-nutritive sucking habits in children". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021 (3): CD008694. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008694.pub2. PMC 8482062. PMID 25825863.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Report in ''Science Daily''. Sciencedaily.com (2005-12-08). Retrieved on 2013-04-14.

- Li, De-Kun; Willinger, Marian; Petitti, Diana B.; Odouli, Roxana; Liu, Liyan; Hoffman, Howard J. (2005-12-09). "Use of a dummy (pacifier) during sleep and risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS): population based case-control study". BMJ. 332 (7532): 18–22. doi:10.1136/bmj.38671.640475.55. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 1325127. PMID 16339767.

- Do Pacifiers Reduce the Risk of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome? A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics.aappublications.org. Retrieved on 2013-04-14.

- The Changing Concept of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. Aappolicy.aappublications.org. Retrieved on 2013-04-14.

- Horne RS; Hauck FR; Moon RY; L'hoir MP; Blair PS (2014). "Dummy (pacifier) use and sudden infant death syndrome: potential advantages and disadvantages". J Paediatr Child Health. 50 (3): 170–4. doi:10.1111/jpc.12402. PMID 24674245. S2CID 23184656.

- Blass EM, Watt LB (1999). "Suckling- and sucrose-induced analgesia in human newborns". Pain. 83 (3): 611–23. doi:10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00166-9. PMID 10568870. S2CID 1695984.

- Curtis SJ, Jou H, Ali S, Vandermeer B, Klassen T (2007). "A randomized controlled trial of sucrose and/or pacifier as analgesia for infants receiving venipuncture in a pediatric emergency department". BMC Pediatrics. 7: 27. doi:10.1186/1471-2431-7-27. PMC 1950500. PMID 17640375.

- Zardetto, Cristina Giovannetti del Conte, Célia Regina Martins Delgado Rodrigues and Fabiane Miron Stefani (2002). "Effects of Different Pacifiers on the Primary Dentition and Oral Myofunctional Structures of Preschool Children". Pediatric Dentistry. 24 (6): 552–559. PMID 12528948.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Thumb, Finger and Pacifier Habits. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. aapd.org

-

Mitchell, E.A., Blair P.S., L'Hoir M.P. (2005). "Should Pacifiers Be Recommended to Prevent Sudden Infant Death Syndrome?". Pediatrics. 117 (5): 1755–1758. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-1625. PMID 16651334. S2CID 19513208.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Dental care for mother and baby. dentalhealth.org

- Passman, R. H., & Halonen, J. S. (1979). "A developmental survey of young children's attachments to inanimate objects". Journal of Genetic Psychology. 134 (2): 165–178. doi:10.1080/00221325.1979.10534051.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Halonen, J. S., & Passman, R. H. (1978). "Pacifiers' effects upon play and separations from the mother for the one-year-old in a novel environment". Infant Behavior and Development. 1: 70–78. doi:10.1016/S0163-6383(78)80010-1.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- "Who Made That Pacifier?", by Dashka Slater, The New York Times Magazine, June 20, 2014

- Information for parents on preventing middle ear infections from PubMed Health