Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia

Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (PSVT) is a type of supraventricular tachycardia, named for its intermittent episodes of abrupt onset and termination.[3][6] Often people have no symptoms.[1] Otherwise symptoms may include palpitations, increased heart rate, feeling lightheaded, sweating, shortness of breath, and chest pain.[2]

| Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Supraventricular tachycardia, paroxysmal atrial tachycardia (PAT)[1] |

| |

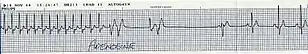

| Lead II electrocardiogram strip showing PSVT with a heart rate of about 180. | |

| Specialty | Emergency medicine, cardiology |

| Symptoms | Palpitations, feeling lightheaded, increased heart rate, sweating, shortness of breath, chest pain[2] |

| Usual onset | Starts and stops suddenly[3] |

| Causes | Not known[3] |

| Risk factors | Alcohol, caffeine, nicotine, psychological stress, Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Electrocardiogram[3] |

| Prevention | Catheter ablation[3] |

| Treatment | Valsalva maneuver, adenosine, calcium channel blockers, synchronized cardioversion[4] |

| Prognosis | Generally good[3] |

| Frequency | 2.3 per 1000 people[5] |

The cause is not known.[3] Risk factors include alcohol, caffeine, nicotine, psychological stress, and Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, which often is inherited.[3] The underlying mechanism typically involves an accessory pathway that results in re-entry.[3] Diagnosis is typically by an electrocardiogram (ECG) which shows narrow QRS complexes and a fast heart rhythm typically between 150 and 240 beats per minute.[3]

Vagal maneuvers, such as the Valsalva maneuver, are often used as the initial treatment.[4] If not effective and the person has a normal blood pressure the medication adenosine may be tried.[4] If adenosine is not effective a calcium channel blocker or beta blocker may be used.[4] Otherwise synchronized cardioversion is the treatment.[4] Future episodes can be prevented by catheter ablation.[3]

About 2.3 per 1000 people have paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia.[5] Problems typically begin in those 12 to 45 years old.[3][5] Women are more often affected than men.[3] Outcomes are generally good in those who otherwise have a normal heart.[3] An ultrasound of the heart may be done to rule out underlying heart problems.[1]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms may include palpitations, feeling faint, sweating, shortness of breath, and chest pain.[2] Episodes start and end suddenly.[3]

Types

- AV nodal re-entrant tachycardia (AVNRT) makes up 56% of cases[5]

- Atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia (AVRT) makes up 27% of cases[5]

- Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome[3]

- Paroxysmal atrial tachycardia makes up 17% of cases[5]

Treatment

AV nodal blocking can be achieved in at least three ways:

Physical maneuvers

A number of physical maneuvers increase the resistance of the AV node to transmit impulses (AV nodal block), principally through activation of the parasympathetic nervous system, conducted to the heart by the vagus nerve. These manipulations are collectively referred to as vagal maneuvers.

The Valsalva maneuver should be the first vagal maneuver tried[7] and works by increasing intra-thoracic pressure and affecting baroreceptors (pressure sensors) within the arch of the aorta. It is carried out by asking the patient to hold his/her breath while trying to exhale forcibly as if straining during a bowel movement. Holding the nose and exhaling against the obstruction has a similar effect.[8] Pressing down gently on the top of closed eyes may also bring heartbeat back to normal rhythm for some people with atrial or supraventricular tachycardia (SVT).[9] This is known as the oculocardiac reflex.

Medications

Adenosine, an ultra-short-acting AV nodal blocking agent, is indicated if vagal maneuvers are not effective.[10] If unsuccessful or the PSVT recurs diltiazem or verapamil are recommended.[4] Adenosine may be safely used during pregnancy.[11]

SVT that does not involve the AV node may respond to other anti-arrhythmic drugs such as sotalol or amiodarone.

Cardioversion

If the person is hemodynamically unstable or other treatments have not been effective, synchronized electrical cardioversion may be used. In children this is often done with a dose of 0.5 to 1 J/Kg.[12]

References

- Ferri, Fred F. (2012). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2013,5 Books in 1, Expert Consult - Online and Print,1: Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2013. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 807. ISBN 978-0323083737. Archived from the original on 2016-10-02.

- "What Are the Signs and Symptoms of an Arrhythmia?". NHLBI. July 1, 2011. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- Al-Zaiti, SS; Magdic, KS (September 2016). "Paroxysmal Supraventricular Tachycardia: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management". Critical Care Nursing Clinics of North America. 28 (3): 309–16. doi:10.1016/j.cnc.2016.04.005. PMID 27484659.

- Neumar, RW; Shuster, M; Callaway, CW; Gent, LM; Atkins, DL; Bhanji, F; Brooks, SC; de Caen, AR; Donnino, MW; Ferrer, JM; Kleinman, ME; Kronick, SL; Lavonas, EJ; Link, MS; Mancini, ME; Morrison, LJ; O'Connor, RE; Samson, RA; Schexnayder, SM; Singletary, EM; Sinz, EH; Travers, AH; Wyckoff, MH; Hazinski, MF (3 November 2015). "Part 1: Executive Summary: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 132 (18 Suppl 2): S315–67. doi:10.1161/cir.0000000000000252. PMID 26472989.

- Katritsis, Demosthenes G.; Camm, A. John; Gersh, Bernard J. (2016). Clinical Cardiology: Current Practice Guidelines. Oxford University Press. p. 538. ISBN 9780198733324. Archived from the original on 2016-10-02.

- "Types of Arrhythmia". NHLBI. July 1, 2011. Archived from the original on June 7, 2015. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- "BestBets: Comparing Valsalva manoeuvre with carotid sinus massage in adults with supraventricular tachycardia". Archived from the original on 2010-06-16.

- Vibhuti N, Singh; Monika Gugneja (2005-08-22). "Supraventricular Tachycardia". eMedicineHealth.com. Archived from the original on 2008-12-16. Retrieved 2008-11-28.

- "Tachycardia | Fast Heart Rate". American Heart Association. Archived from the original on 12 April 2013. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- "Adenosine vs Verapamil (calcium channel blocker) in the acute treatment of supraventricular tachycardias". Archived from the original on 2010-06-16.

- Blomström-Lundqvist ET AL., MANAGEMENT OF PATIENTS WITH Supraventricular Arrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:1493–531 "Supraventricular Arrhythmias Guideline Update". Archived from the original on 2009-03-10. Retrieved 2010-01-17.

- de Caen, AR; Berg, MD; Chameides, L; Gooden, CK; Hickey, RW; Scott, HF; Sutton, RM; Tijssen, JA; Topjian, A; van der Jagt, ÉW; Schexnayder, SM; Samson, RA (3 November 2015). "Part 12: Pediatric Advanced Life Support: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 132 (18 Suppl 2): S526–42. doi:10.1161/cir.0000000000000266. PMC 6191296. PMID 26473000.