Peganum harmala

Peganum harmala, commonly called wild rue,[1] Syrian rue,[1] African rue,[1] esfand or espand,[6] or harmel,[1] (among other similar pronunciations and spellings) is a perennial, herbaceous plant, with a woody underground root-stock, of the family Nitrariaceae, usually growing in saline soils in temperate desert and Mediterranean regions. Its common English-language name came about because of a resemblance to rue (to which it is not related). Because eating it can cause livestock to sicken or die, it is considered a noxious weed in a number of countries. It has become an invasive species in some regions of the western United States. The plant is popular in Middle Eastern and north African folk medicine. The alkaloids contained in the plant, including the seeds, are monoamine oxidase inhibitors (Harmine, Harmaline).[7]

| Peganum harmala | |

|---|---|

| |

| Harmal (Peganum harmala) flower | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Sapindales |

| Family: | Nitrariaceae |

| Genus: | Peganum |

| Species: | P. harmala |

| Binomial name | |

| Peganum harmala L.[1] | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Etymology

African rue is often used in North American English.[1][8][9][10][11]

Harmel is used in India,[1] Algeria,[12] and Morocco.

It is known in as اسپند in Persian, which is transliterated as espand,[6] or ispand[13] but may also be pronounced or transliterated as sepand, sipand, sifand, esfand, isfand, aspand, or esphand depending on source or dialect.[14][15] The Persian word اسپند is also the name of the last month of the year, approximately March, in the traditional Persian calendar.[16][17] It is derived from Middle Persian spand, which is thought, along with the English word spinach, to be ultimately derived from Proto-Iranian *spanta-, 'holy' (compare Avestan 𐬯𐬞𐬆𐬧𐬙𐬀, spəṇta, 'holy', and Middle Persian spenāg, 'holy'), itself thought to be ultimately derived from Proto-Indo-European *ḱwen-.[18]

It is known as spilani in Pashto.[19] In Urdu it is known as harmal, ispand, or isband.[2] In Turkish it is known as uzerlik or sedefotu.[20] In Chinese it is 驼驼蒿, tuó tuó hāo,[21] or 骆驼蓬, luo tuó peng.[22]

In Spain it is known as hármala,[23] alharma or gamarza,[1] amongst dozens of other local names.[23][24] In French it is known as harmal.[25]

Description

Habitus

It is a perennial, herbaceous, suffrutescent, hemicryptophyte plant, which dies off in the winter, but regrows from the rootstock the following spring.[8][9][10][22][26] It can grow to about 0.8 m (3 ft) tall,[8] but normally it is about 0.3 m (1 ft) tall.[9] The entire plant is hairless (glabrous).[2][22] Plants are bad tasting[22] and smell foul when crushed.[10]

Stems

Numerous erect to spreading stems grow from the crown of the root-stock in the spring,[22][23] these branch in a corymbose fashion.[2][22]

Roots

The roots of the plant can reach a depth of up to 6.1 m (20 ft), if the soil where it is growing is very dry.[9] The roots can grow to 2 cm (0.8 in) thick.[22]

Leaves

The leaves are alternate,[22][26] sessile,[2] and have bristly, 1.5–2.5 mm (0.06–0.10 in) long stipules at the base.[2][26] The leaf blade is dissected/forked twice or more into three to five thin, linear to lanceolate-linear, greyish lobes.[22][26] The forks are irregular.[2] The lobes have smooth margins,[26] are 3–5 cm (1.2–2.0 in) long[2] and 1–5 mm (0.04–0.20 in) broad,[2][22] and end in points.[2]

Flowers

It blooms with solitary flowers[25] opposite to the leaves on the apical parts of branches.[22] It flowers between March and October in India,[27][28][29] between April and October in Pakistan,[2] between May and June in China,[22] between March and April in Palestine,[26] and between May and July in Morocco.[30] The flowers are white[2][10][12][31] or yellowish white,[2][22] and are about 2–3 cm in diameter.[2][31] Greenish veins are visible in the petals.[10] They have a threadlike, 1.2 cm long pedicel.[2] The flowers have five (10-)12–15(−20)mm long,[2][12][22] linear, pointy-ended, glabrous sepals, often divided into lobes,[2][22] although sometimes entire and only divided at the end.[2][22] There are five petals which are oblong-elliptic, obovate to oblong in shape, (10-)14–15(−20)mm long, (5-)6–8(−9)mm broad, and ending with an obtuse apex.[2][22] The flowers are hermaphroditic, having both male and female organs.[25] The flowers usually have 15 stamens (rarely fewer);[2][22] these have a 4-5mm long[2] filament with an enlarged base.[10][22] The dorsifixed, 6mm long anthers are longer than the filaments.[2] The ovary is superior,[32] and has 3 locules[22] and ends in an 8-10mm long style, the ending 6mm of which are triangular or 3-keeled in cross-section.[2] The ovary is surrounded by a nectary which is glabrous and has five lobes in a regular pattern.[32]

The flowers produce only a tiny amount of nectar. The nectar is rich in hexose sugars. It contains a relatively small concentration of amino acids among which there is an especially high amount of the glutamic acid, tyrosine and proline, the last of which can be tasted by, and is favoured by, many insects. It also contains (four) alkaloids, in relatively high concentration compared to the flowers of other species, among them the toxins harmalol and harmine. The proportions and concentrations of the alkaloids in the nectar are different than in the other organs of the plant, indicating an adaptive reason for their presence.[32]

Pollen

P. harmala has smallish, tricolpate pollen grains with a rugulate-reticulate surface. The exine has a sexine which is thicker than the nexine. These grains are well distinguishable from pollen of related plants (Nitraria) in Pakistan.[33]

.jpg.webp)

Fruit

The plant fruits between July and November in China.[22] The fruit is a dry, round seed capsule[2][10][34] which measures about 6–10(−15) mm in diameter,[2][34] These seed capsules have three chambers and carry more than 50 seeds.[2][31] The end of the fruit is usually somewhat sunken inwards[2][12] and retains a persistent style.[2]

Distribution

Native

Peganum harmala is native to a wide area stretching from Morocco in north Africa and Spain and Italy in Europe, north to Serbia, Romania (possibly), Dagestan and Kazakhstan, south to Mauritania (possibly), Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Pakistan, and east to western Mongolia, northern China and possibly Bangladesh.[1][3] It is a common weed in Afghanistan, Iran,[6][36] parts of Israel,[37] eastern and central Anatolia (Turkey),[20] and Morocco.

In Africa it is known from Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt.[4] It likely does not occur in Mauritania.[4][38][39] In Morocco it is quite common and occurs throughout the country, excepting Western Sahara.[4][30][38][39] In Algeria it is found mostly in the north bordering Morocco and Tunisia, being absent in the south and central regions.[12][38][39] It is reasonably commonly found throughout Tunisia.[38][40] In Libya it is found in the maritime zone, especially around Bengazi, and is not abundant.[41] In Egypt it grows in the Sinai,[1][4][38] has been recorded from the east of the Eastern Desert,[42] and been rarely collected on the mid-west of the Mediterranean coast.[38]

In Europe it is native to Spain, Corsica (disputed), much of Russia, Serbia, Moldova, Ukraine (especially in Crimea), Romania (possibly introduced), Bulgaria, Greece (including Crete and the Cyclades), Cyprus, Turkey (Thrace) and southern Italy (including Sardinia, but not Sicily). It also is native to the Caucasus: Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia.[24][25][38] On the Iberian Peninsula it is absent from Portugal and Andorra, but it is not uncommon in Spain, especially in the southeast, the Ebro depression, and the inland valleys of the Duero and Tajo, but it is rare in Andalusia (south) and it does not occur on the Balearic Islands and the Canary Islands, and in the west along the Portuguese border, Galicia, the northern coast, and the northern mountain ranges.[23][38][43]

In Turkey it is found both in Thrace and across most of Anatolia, but is absent from the northern Black Sea coast. It is abundant in some regions of south and central Anatolia.[20]

In Israel it is most commonly found around the Dead Sea, in the Judean mountains and desert, in the Negev and its surrounding areas, including areas in Jordan and Saudi Arabia, being rare or very rare in the northern mountains, Galilee, coastal areas and the Arava valley.[26]

It grows in drier parts of the northern half of India[28][29][38][44] but is possibly only native to the Kashmir and Ladakh regions.[1][27] It also occurs in, and is possibly native to, Bangladesh.[3][45]

The distribution in China is in dispute. The 2008 Flora of China considers it to be native to northern China in the provinces of Gansu, western Hebei, western Inner Mongolia, Ningxia, Qinghai, northern Shanxi, Tibet and Xinjiang.[22] The 2017 Species Catalogue of China considers it to be restricted to Inner Mongolia, Ningxia and Gansu.[21]

Adventive distribution

It has been added to the lists of the Global Register of Introduced and Invasive Species for the countries of South Africa, Mexico, France and Ukraine, although it is not reported as having a negative impact in any of these countries.[38] Most Ukrainian and other references consider the plant native to Ukraine.[24] Sources are in disagreement regarding rare collections in coastal Romania, but many consider it introduced.[3][24][38] At least 7 occurrences have been registered in South Africa, and none in Mexico (as of 2017).[38] As of 2020 it is included in South African National Biodiversity Institute's Plants of Southern Africa website as an introduced plant to South Africa.[46] One database has it occurring as a non-native in Hungary.[3]

In France it is considered a former accidental introduction once uncommonly found on the Côte d'Azur along the Mediterranean coast.[25][38] It has very rarely been found elsewhere in France in the past.[38] According to the Flora Europaea there is a native population on Corsica,[24] however, according to Tela Botanica it does not occur on the island, either as a native or not.[25]

It was first planted in the United States in 1928 in New Mexico by a farmer wanting to manufacture a dye called "Turkish red" from its seeds.[9] From here the plant spread over most of southern New Mexico and the Big Bend region of Texas. An additional spread has occurred from east of Los Angeles in California to the tip of southernmost Nevada. Outside of these regions the distribution in the US is not continuous and localised. As of 2019 it has been reported in southern Arizona (in at least 3 adjacent counties), northeastern Montana (2 adjacent counties), northern Nevada (Churchill county), Oregon (town of Prineville in the Oregon high desert) and possibly Washington.[10][11][47] "Because it is so drought tolerant, African rue can displace the native saltbushes and grasses growing in the salt-desert shrub lands of the Western U.S."[9]

Although the distribution in New Mexico and Texas would suggest it has spread to parts of northern Mexico,[47] the species has not been included in the 2004 list of introduced plants of Mexico.[48]

Habitat and ecology

It grows in dry areas in the United States.[9][10] It can be considered a halophyte.[26][30]

In Kashmir and Ladakh it is known from elevations of 300–2400 m,[27] in China 400–3600 m,[22] in Turkey 0–1500 m,[20] and in Spain 0–1200 m.[23]

In China it grows in slightly saline sands near oases and dry grasslands in desert areas.[22]

In Spain it can be found in abandoned fields, rubbish tips, stony slopes, along the verges of roads, ploughed and worked earth, as well as in disturbed, saline scrubland.[23]

In Morocco it is said to grow in steppes, arid coasts, dry uncultivated fields and amongst ruins.[30] A study in Morocco found that it could be used as an indicator species for rangeland degraded from agricultural activities, when found in association with certain Artemisia sp., Noaea mucronata and Anabasis aphylla.[49] In Israel it is a common dominant plant along with Anabasis syriaca and Haloxylon scoparium in a low semi-shrubby steppe ecosystem which during dry years is almost devoid of plant cover, growing on saline, loess-derived soils. In rainy times Leontice leontopetalum and Ixiolirion tataricum appear here. It also grows in Israel in semi-steppe shrublands, Mediterranean woodlands and shrublands, and deserts.[26] Between 800–1300m elevation on the sandstone slopes of the mountains around Petra, Jordan, there is an open Mediterranean steppe forest dominated by Juniperus phoenicea and Artemisia herba-alba together with occasional trees of Pistacia atlantica and Crataegus aronia with common shrubs being Thymelaea hirsuta, Ephedra campylopoda, Ononis natrix, Hammada salicornia and Anabasis articulata; when this habitat is further degraded (it is already degraded) by overgrazing P. harmala along with Noaea mucronata invade.[50] It is often found with Euphorbia virgata in the foothills of Mount Ararat, Iğdır Province, Turkey.[20]

The flowers are pollinated by insects.[25] Little is known about pollen vectors.[32] A year-long study around the town of St. Katherine in the El-Tur mountains of southern Sinai found P. harmala to be exclusively pollinated by the domesticated honey bee, Apis mellifera, although it is possible these animals are displacing native bees.[51] The floral morphology, nectar amount and composition – high in hexane sugars, presence of toxic alkaloids and high proline content together suggest pollination by short-tongued bees (see pollination syndrome).[32]

Regarding seed dispersal it is considered a barochore.[25] According to a Mongolian study, its seeds are exclusively dispersed by human activities, although Peganum multisectum, sometimes seen as a variety or synonym of this species, is dispersed solely by water flow.[52]

A species of tiny, hairy beetle, Thamnurgus pegani, has been found inhabiting stems of P. harmala in Turkey and elsewhere. It feeds only on P. harmala. When the aerial parts of the plant begin to die off in the autumn, the adult beetles retreat to overwinter in the soil underneath the root-crown, or in old larval tunnels in the dead stems; emerging in the spring (May in Turkey), the females bore small holes in the now shooting stems of the plant, in which they lay their eggs. The hatched larvae bore inward toward the pith. The beetles somehow infect the surrounding tissue in the tunnels with a fungus, Fusarium oxysporum. The infected plant tissue turns blackish and is then used by the adult beetles and their larvae as a food source, until they are ready to pupate within the stem tunnels. It has been proposed as a candidate for using in biological control of P. harmala, as a relative of it, T. euphorbiae, has been approved for use against invasive Euphorbia in the United States.[20]

History

As the plant is popular in Persian cultural traditions, and is a hallucinogen, the linguists David Flattery and Martin Schwartz wrote a book in 1989 in which they theorised that the plant is the Avestan haoma mentioned in ancient Persian Zoroastrian texts. The transcribed word haoma is thought to be likely related to the Vedic word soma; these names refer to a magical, purportedly entheogenic plant/drink that is mentioned in ancient Indo-Iranian texts but whose exact identity has been lost to history.[53][54]

This plant was first described in a recognisable manner under the name πήγανον ἄγριον (péganon agrion) by Dioscorides, who mentions it is called μῶλυ (moly) in parts of Anatolia (although Dioscorides distinguishes the 'real' μῶλυ as another, bulbaceous plant). Galen later describes the plant under the name μῶλυ, following Dioscorides by mentioning numerous other names it was known by: ἅρμολαν, armolan (harmala), πήγανον ἄγριον and in Syria βησασὰν, besasan (besasa). For much of the subsequent history of Europe Galen was seen as the pinnacle of human medical knowledge. As such, during the early Middle Ages, the herb was known as moly or herba immolum.[55]

The 12th century Arab agriculturist Ibn al-'Awwam from Seville, Spain, wrote that the seeds were used in the baking of bread; the fumes being used to facilitate fermentation and help with the taste (he usually quotes older authors).[56]

By the mid-16th century Dodoens relates how apothecaries sold the plant under the name harmel as a type of extra-strength rue.[57]

Taxonomy

Rembert Dodoens in 1553 illustrated and described the plant (republished 1583 with better illustration, calling it Harmala, and basing his work on Galen and Dioscorides).[58][59]

In 1596 Gaspard Bauhin had his Phytopinax published in which he attempted to list all plants known in an ordered manner. He judges Ruta sylvestris Dioscorides to be a type of Hypericum.[60] Later, in his Pinax Theatri Botanici of 1623 he attempts to sort the synonymy in all the previously published names by the botanists from earlier in history. In this work he sorts Ruta into five species, distinguishing this plant from the others by its three-locular fruit, large white flowers and being only known as a wild plant (as opposed to cultivated). He considers his 'Ruta sylvestris flore magno albo' (=Peganum harmala) to be (not all writers named in the following): Tabernaemontanus', Dodoens' and Clusius' Harmala; Matthias de l'Obel's Harmala syriaca; Andreas Cæsalpinus' and Conrad Gesner's (in his report on Ottoman plants) Harmel; Pietro Andrea Mattioli's and Clusius' (in another work) Ruta sylvestris Harmala; Valerius Cordus' (in his Annotations on Dioscorides), Gesner's (in his Hortus), and Aloysius Anguillara's Ruta sylvestris; and Castore Durante's and Joachim Camerarius the Younger's Ruta sylvestris secunda.[61]

In 1753 Carl Linnaeus named the species Peganum harmala. He cites this species as based on Bauhin's Pinax Theatri Botanici of 1623, and Stirpium Historiae Pemptades Sex of 1583 by Rembert Dodoens.[62]

Type

In 1954 Brian Laurence Burtt and Patricia Lewis designated 'Cult. in Horto Upsaliensi (Linn!)' as the lectotype for the species.[63] This lectotype appeared to be two sheets (621.1 and 621.2) in the Linnean Herbarium, not being part of a single gathering, and hence ICBN Art. 9.15 (Vienna Code) did not apply.[64] In 1993 Mohammed Nabil El Hadidi designated 'Clifford Herbarium 206, Peganum no. 1', stored at the British Museum of Natural History, as the lectotype for P. harmala.[65][66]

Infraspecific variability

Peganum harmala var. garamantum – P. harmala var. garamantum was originally described by René Maire in 1953 in his Flore de l'Afrique du Nord.[4] It was still recognised as occurring in Tunisia as of 2010 (along with var. typicum),[40] although the distinction is not recognised in other works.[4]

Peganum harmala var. grandiflorum – El Hadidi described P. harmala var. grandiflorum in 1972 for the Flora Iranica based on herbarium material collected by H. Bobek in Tal Shahdad in Kerman Province, Iran in 1956, and said the variety grew in both Iran and Afghanistan. It was subsequently collected only once more, at least as recorded in the GBIF, in 1980 in Spain near the bank of the Ebro river approximately halfway downriver to the sea from Zaragosa.[67][68] It is not mentioned in the Flora Iberica.[23]

Peganum harmala var. multisecta – First described by Karl Maximovich in 1889 from Qinghai.[69][70] Sometimes incorrectly spelled var. multisectum.[71][72] Occurs in Dzungaria, Hexi, Qaidam Basin, Ordos and the Altai regions in China and Mongolia.[52][70] In China it occurs in the provinces of Inner Mongolia, northern Shanxi, Ningxia, Gansu, Qinghai, Xinjiang and Tibet[21][22] (the Flora of China claims it is endemic to China).[22] It can be distinguished by having the sepals (called 'calyx leaves' in one study) incised with 3–5 lobes, instead of being entire as in the nominate form[52][70] (P. nigellastrum, which also occurs in the region, has this characteristic even more pronounced, but with the calyx leaves split into 5–7 thin string-like lobes), and by having leaves which are more dissected or may be trisected.[52] The leaves are dissected to 3–5 lobes in the nominate form – the individual leaf lobes being 1.5–3 mm wide, whereas this variety always has more than 5 lobes 1–1.5 mm wide.[22] The nominate form has seeds with a depressed surface, whereas var. multisecta has seeds with convex surface.[52] Furthermore, the stems of this variety sprawl prostrate upon the ground, whereas the nominate has erect stems, and the variety has stems which are pubescent when young as opposed to always glabrous.[22] Some consider it better to classify it as an independent species, P. multisectum (fide Bobrov, 1949).[21][52][71][72][22][73] Others consider it a synonym of the nominate form.[69]

Peganum harmala var. rothschildianum – Originally described by cactus specialist Franz Buxbaum in 1927 as P. rothschildianum from northern Africa. Subsumed as a variety by René Maire in 1953. Not recognised for Tunisia, nor elsewhere.[4][40]

Peganum harmala var. stenophyllum – This variety is still accepted by some authorities,[29][74] although it is not recognised in the Flora of Pakistan.[2] Pierre Edmond Boissier described it in 1867[29] and it has been recognised as growing in Iran,[29][74][75] Iraq,[29] Afghanistan,[29][74][75] Pakistan,[29][74][75] India,[29][74] Tajikistan,[74] and the northern Caucasus.[74] In India it is found in Kashmir, Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Gujarat, Maharashtra and Karnataka.[29] It can be distinguished from the nominate form by having finer leaves with more narrow lobes, shorter sepals and broader-shaped seed capsules.[29][52]

Toxicity

Legal issues

In the United States, it is considered an invasive, noxious weed in the following states: Arizona (prohibited noxious weed), California (A listed noxious weed), Colorado (A listed noxious weed), Nevada (noxious weed), New Mexico (class B noxious weed), and Oregon (A designated weed, under quarantine). This may require land owners to exterminate infestations on their land or be fined, and allows access to government grants to buy herbicides to do so. It is illegal to sell plants of this species in the states listed above.[11][76][77][78] Since 2005, with caveats, the cultivation, possession or sale of this species is also illegal in Louisiana.

Since 2005 the possession of the seeds, the plant itself, and the alkaloids harmine and harmaline, which it contains, is illegal in France.[79] In Finland, the plant is officially listed as a medicinal plant, which means one would require a doctors prescription to acquire it. In Canada, harmaline is illegal. In Australia, harmala alkaloids are illegal.

Uses

Weed and livestock poisoning

In some regions it is a common weed.[36] In China it is seen as a noxious weed,[22] invasive in overgrazed areas.[22] In the United States, where it is not native, it is officially registered as a noxious weed or similar designation in Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico and Oregon.[11] Infestations can be invasive and very difficult to exterminate.[9][76] It is also known as an agricultural seed contaminant. It often causes livestock poisonings,[1] especially during drought. Consumption by animals causes reduced fertility and abortions.[80]

Control is possible only with powerful herbicides. Manually uprooting the plants is near impossible[76] and there are no methods of biological control currently awaiting approval.[20] The rootstock contains starches that help the plant survive being defoliated and is thick and grows very deep, and the crown of the plant is safe below the surface.[76]

Dyes

A red dye, "Turkey red",[81] from the seeds (but usually obtained from madder) is often used in western Asia to dye carpets. It is also used to dye wool. When the seeds are extracted with water, a yellow fluorescent dye is obtained.[82] If they are extracted with alcohol, a red dye is obtained.[82] The stems, roots and seeds can be used to make inks, stains and tattoos.[83] According to one source, for a time the traditional Ottoman fez was dyed with the extract from this plant.[23]

Traditional medicine and superstitions

In Iran and neighbouring countries such as Turkey, dried capsules from the plant are strung and hung in homes or vehicles to protect against "the evil eye".[84][14] It is widely used for protection against Djinn in Morocco (see Légey "Essai de Folklore marocain", 1926).

Esfand (called isband in Kashmiri) is burnt in Kashmiri Hindu weddings to create an auspicious atmosphere.[85] Burning esfand seeds is also common in Persian cultures for warding off the evil eye, as in Persian weddings.[14]

In Yemen, the Jewish custom of old was to bleach wheaten flour on Passover, in order to produce a clean and white unleavened bread. This was done by spreading whole wheat kernels upon a floor, and then spreading stratified layers of African rue (Peganum harmala) leaves upon the wheat kernels; a layer of wheat followed by a layer of Wild rue, which process was repeated until all wheat had been covered over with the astringent leaves of this plant. The wheat was left in this state for a few days, until the outer kernels of the wheat were bleached by the astringent vapors emitted by the wild rue. Afterwards, the wheat was taken up and sifted, to rid them of the residue of leaves. They were then ground into flour, which left a clean and white batch of flour.[86]

Peganum harmala has been used as an analgesic,[87] emmenagogue, and abortifacient agent.[88][89][90]

In a certain region of India the root was applied to kill body lice.[44]

It is also used as an anthelmintic (to expel parasitic worms). Reportedly, the ancient Greeks used the powdered seeds to get rid of tapeworms and to treat recurring fevers (possibly malaria).[91]

As related in Des Cruydboeks of 1554 by Rembert Dodoens, in Europe this plant was considered to be a wild type of rue and identical in medicinal uses -the identity of the two plants and their Ancient Greek and Roman uses had merged, though it was considered stronger, even dangerously so. It could be bought under the name harmel in the apothecaries, and was also known as 'wild' or 'mountain' rue. It could be used for a few dozen ailments, such as to treat woman of their natural disease when the leaves were used in only water, or when the juice were drunk with wine and the leaves pressed against the wound it could cure bites and stings from rabid dogs, scorpions, bees and wasps and the like. From supposedly Pliny he relates how those covered in the sap, or having eaten it sober, would be immune to poison for a day, as well as to poisonous beasts. Other cures were for 'drying' sperm, 'purifying' woman after childbirth, curing earache, getting rid of spots and blemishes on the skin, and soothing bumps and pain caused by hitting a something, among many others. All the cures call for either juice or the leaves; none call for the seeds.[57]

Entheogenic use

Peganum harmala seeds have been used as a substitute for Banisteriopsis caapi in ayahuasca analogs, as they contain monoamine oxidase inhibitors that enable DMT to be orally active.[92]

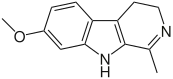

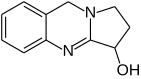

Alkaloids

Seed alkaloids

Total harmala alkaloids were at least 5.9% of dried weight, in one study.[93]

| Beta-carboline[94] | Content |

|---|---|

| 1-hydroxy-7-methoxy-β-carboline | |

| 2-aldehyde-tetrahydroharmine | |

| 3-hydroxylated harmine | |

| 6-methoxytetrahydro-1-norharmanone | |

| 8-hydroxy-harmine | |

| Acetylnorharmine | |

| Desoxypeganine[95] | |

| Dihydroruine | |

| Dipegene | |

| Harmalacidine (HMC) | |

| Harmalacinine | |

| Harmalanine | |

| Harmalicine | |

| Harmalidine | |

| Harmaline (dihydroharmine, DHH, harmidine) | 0.25%[93]–0.79%[96]–5.6%[97] |

| Harmalol | 0.6%[97]–3.90%[93] |

| Harmane (harman) | 0.16%[93] |

| Harmic acid | |

| Harmic acid methyl ester | |

| Harmine (banisterine, telepathinec, yageine) | 0.44%[96]–1.84%[93]–4.3%[97] – The coatings of the seeds are said to contain large amounts of harmine.[8] |

| Harmine N-oxide | |

| Harmol | |

| Isoharmine | |

| Isopeganine | |

| Norharman | |

| Norharmine (tetrahydro-beta-carboline) | |

| Pegaharmine A | |

| Pegaharmine B | |

| Pegaharmine C | |

| Pegaharmine D | |

| Pegaharmine E | |

| Pegaharmine F | |

| Pegaharmine G | |

| Pegaharmine H | |

| Pegaharmine I | |

| Pegaharmine J | |

| Pegaharmine K | |

| Peganine A | |

| Peganine B | |

| Peganumal A | |

| Peganumal B | |

| Peganumine A | |

| Peganumine B | |

| Ruine | |

| Tetrahydroharman | |

| Tetrahydroharmine (THH, leptaflorine) | 0.1%[97] |

| Tetrahydroharmol | |

| Tetrahydronorharman |

References

- "Peganum harmala". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved 17 February 2008.

- Ghafoor, Abdul (1974). Nasir, E.; Ali, S. I. (eds.). Flora of Pakistan, Vol. 76 Zygophyllaceae. Karachi: Missouri Botanical Garden Press and the University of Karachi. p. 7.

- "Peganum harmala L." Plants of the World Online, Kew Science. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. 2019. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- "CJB – African plant database – Detail". African plant database. Conservatoire et Jardin botaniques & South African National Biodiversity Institute. 2012. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- "The Plant List: A Working List of all Plant Species".

- Mahmoud Omidsalar Esfand: a common weed found in Persia, Central Asia, and the adjacent areas Encyclopedia Iranica Vol. VIII, Fasc. 6, pp. 583–584. Originally published: 15 December 1998. Online version last updated 19 January 2012

- Massaro, Edward J. (2002). Handbook of Neurotoxicology. Humana Press. p. 237. ISBN 978-0-89603-796-0.

- "African rue or Harmel". cdfa.ca.gov. Archived from the original on 22 October 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- Davison, Jay; Wargo, Mike (2001). Recognition and Control of African Rue in Nevada (PDF). University of Nevada, Reno. OCLC 50788872.

- Kleinman, Russ. "Vascular Plants of the Gila Wilderness". Vascular Plants of the Gila Wilderness. Western New Mexico University Department of Natural Sciences & the Dale A. Zimmerman Herbarium. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- "PLANTS Profile for Peganum harmala (harmal peganum) / USDA PLANTS". USDA. 17 January 2008. Retrieved 18 January 2008.

- Battandier, Jules-Aimé; Trabut, Louis-Charles (1888). Flore de l'Algérie, Dicotylédones (in French). Paris: Librairie F. Savy. p. 179.

- Steingass, F. (1892). A Comprehensive Persian-English Dictionary. p. 48.

- "Esphand Against the Evil Eye in Zoroastrian Magic". Lucky Mojo dot com.

- Steingass, Francis Joseph (1892). A Comprehensive Persian–English dictionary. London: Routledge & K. Paul. p. 652.

- Jahanshiri, Ali (2019). "Months and Seasons – Persian Vocabulary". Ali Jahanshiri. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- Price, Massoume (15 April 1999). "Filling the shells – Names of Persian months and their forgotten meanings". The Iranian. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- MacKenzie, David Neil (1971). A concise Pahlavi dictionary. London: Oxford University Press. p. 76. ISBN 9781136613968.

- Flattery, D.S. & Schwartz, M. (1989). Historical and geographical availablitity of Harmel. Table 1: Some names for Geganum harmala L. Haoma and Harmaline: The Botanical Identity of the Indo-Iranian Sacred Hallucinogen "Soma" and its Legacy in Religion, Language, and Middle Eastern Folklore: 42; University of California Publications, Near Eastern Studies Volume 21.

- Güclü, Coskun; Özbek, Hikmet (2007). "Biology and damage of Thamnurgus pegani Eggers (Coleoptera: Scolytidae) feeding on Peganum Harmala L. in Eastern Turkey". Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington. 109: 350–358. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- "Species Catalogue of China, Plants". 中国 生物物种名录 植物卷 (in Chinese). Beijing: Science Press. 2017. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- Liu, Yingxin; Zhou, Lihua (18 April 2008). "Peganaceae". In Zhengyi (吴征镒), Wu; Raven, Peter H.; Deyuan (洪德元), Hong (eds.). Flora of China, Vol. 11. Beijing: Science Press. p. 43.

- Güemes, J.; Sánchez Gómez, P. (2015). Flora iberica, Vol. IX (PDF) (in Spanish). Madrid: Real Jardín Botánico. pp. 148–151. ISBN 978-84-00-09986-2.

- Castroviejo, Santiago (2009). "Zygophyllaceae, The Euro+Med Plantbase Project". Euro-Mediterranean Plant Base. Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum Berlin-Dahlem. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- "eFlore". Tela Botanica (in French). 2019. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- Danin, Avinoam; Fragman-Sapir, Ori (2019). "Peganum harmala L. – Flora of Israel Online". Flora of Israel Online. Avinoam Danin. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- "Peganum harmala – harmal". Flowers of India. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- "Botanical Survey of India, Peganum harmala var. harmala". eFlora of India. Government of India, Ministry of Environment and Forest & Climate Change. 2014. Archived from the original on 23 February 2019. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- "Botanical Survey of India, Peganum harmala var. stenophyllum". eFlora of India. Government of India, Ministry of Environment and Forest & Climate Change. 2014. Archived from the original on 23 February 2019. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Jahandiez, Émile; Maire, René Charles Joseph Ernest (1932). Catalogue des plantes du Maroc. Tome deuxiéme. Dicotylédones Archichalamydées (in French). Algiers: Imprimerie Minerva. p. 453.

- "Erowid Syrian Rue Vaults: Smoking Rue Extract / Harmala". erowid.org. Retrieved 1 December 2008.

- Movafeghi, Ali; Abedini, Masumeh; Fatemeh, Fathiazad; Aliasgharpour, M.; Omidi, Y. (15 February 2009). "Floral nectar composition of Peganum harmala L". Natural Product Research. 23 (3): 301–308. doi:10.1080/14786410802076291. PMID 19235031. S2CID 205835264.

- Perveen, Anjum; Qaiser, Mohammad (2006). "Pollen Flora of Pakistan –XLIX. Zygophyllaceae" (PDF). Pakistan Journal of Botany. 38 (2): 225–232. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- "Lycaeum > Leda > Peganum harmala". leda.lycaeum.org. Archived from the original on 19 February 2007. Retrieved 1 December 2008.

- "Peganum harmala L." Tropicos. Missouri Botanical Garden. 2019. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- Mahmoudian, Massoud; Hossein, Jalilpour; Salehian, Pirooz (Autumn 2002). "Toxicity of Peganum harmala: Review and a Case Report". Iranian Journal of Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 1 (1): 1–4.

- Shapira, Zvia; Terkel, J.; Egozic, Y.; Nyskad, A.; Friedman, J. (December 1989). "Abortifacient potential for the epigeal parts of Peganum harmala". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 27 (3): 319–325. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(89)90006-8. PMID 2615437.

- "Peganum harmala L." GBIF Backbone Taxonomy, Checklist dataset (Data Set). GBIF Secretariat. 2017. doi:10.15468/39omei. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- Volpato, Gabriele; Emhamed, Abdalahe Ahmadi; Saleh, Saleh Mohamed Lamin; Broglia, Alessandro; di Lello, Sara (December 2007). "11. Procurement of traditional remedies and transmission of medicinal knowledge among Sahrawi people displaced in Southwestern Algerian refugee camps" (PDF). In Pieroni, Andrea; Vandebroek, Ina (eds.). Traveling Plants and Cultures, The Ethnobiology and Ethnopharmacy of Migrations. Oxford: Berghahn. pp. 364, 381. ISBN 978-1-84545-373-2.

- Le Floc’h, Edouard; Boulos, Loutfy; Véla, Errol (2010). Catalogue synonymique commenté de la Flore de Tunisie (in French). Tunis: République Tunisienne, Ministère de l’Environnement et du Développement Durable, Banque Nationale de Gènes. pp. 24, 277.

- Pampanini, Renato (1930). Prodromo della flora Cirenaica (in Italian). Forlì: Ministero delle Colonie (Tipografia Valbonesi). pp. 301–302.

- Abd El-Ghani, Monier; Salama, Fawzy; Salem, Boshra; El-Hadidy, Azza; Abdel-Aleem, Mohamed (2017). "Phytogeography of the Eastern Desert flora of Egypt" (PDF). Wulfenia. 24: 118–119. S2CID 158865290.

- "Anthos. Sistema de información sobre las plantas de España". Anthos (in Spanish). Ministerio de Agricultura, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente, y Real Jardín Botánico. 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- Chopra, Ram Nath; Chopra, Ishwar Chander; Nayar, S. L. (1956). Glossary of Indian Medicinal Plants. New Delhi: Council of Scientific and Industrial Research.

- Mostaph, M.K.; Uddin, S.B. (2013). Dictionary of plant names of Bangladesh, Vasc. Pl. Chittagong: Janokalyan Prokashani. pp. 1–434.

- "Plants of Southern Africa". South African National Biodiversity Institute. 7 October 2020. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- "Peganum harmala". SEINet Portal Network. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- Villaseñor, José Luis; Espinosa-García, Francisco J. (2004). "The alien flowering plants of Mexico". Diversity and Distributions. 10 (2): 113–123. doi:10.1111/j.1366-9516.2004.00059.x.

- Mahyou, Hamid; Tychon, Bernard; Balaghi, Riad; Louhaichi, Mounir; Mimouni, Jamal (8 January 2016). "A Knowledge‐Based Approach for Mapping Land Degradation in the Arid Rangelands of North Africa". Land Degradation & Development. 27 (6): 1574–1585. doi:10.1002/ldr.2470.

- Fall, Patricia L. (1 January 1990). "Deforestation in Southern Jordan; Evidence from fossil Hyrax middens". In Bottema, S.; Entjes-Nieborg, G.; van Zeist, W. (eds.). Man's Role in the Shaping of the Eastern Mediterranean Landscape, Proceedings of the Symposium on the Impact of Ancient Man on the Landscape of the E Med Region & the Near East, Groningen, March 1989. Rotterdam: Balkema. p. 274.

- Semida, Fayez; Elbanna, Shereen (January 2006). "Impact of Introduced Honey Bees on Native Bees at St. Katherine Protectorate, South Sinai, Egypt". International Journal of Agriculture and Biology. 8 (2): 191–194.

- Amartuvshin, Narantsetseg; Dariimaa, Shagdar; Tserenbaljid, Gonchig (2006). "Taxonomy of the Genus Peganum L. (Peganaceae Van Tieghem) in Mongolia". Mongolian Journal of Biological Sciences. 4 (2): 9–13. doi:10.22353/mjbs.2006.04.10.

- Flattery, David Stophlet; Schwartz, Martin (1989). Haoma and Harmaline: The Botanical Identity of the Indo-Iranian Sacred Hallucinogen "Soma" and its Legacy in Religion, Language, and Middle Eastern Folklore. University of California Publications Near Eastern Studies. Vol. 21. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-09627-1.

- Karel van der Torn, ed., "Haoma," Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible. (New York: E.J. Brill, 1995), 730.

- Zergi, Nóra (2010). "ΜΩΛΥ". In Czeglédy, Anita; Horváth, László; Krähling, Edit; Laczkó, Krisztina; Ligeti, Dávid Ádám; Mayer, Gyula (eds.). Pietas non-sola Romana – Studia memoriae Stephani Borzsák dedicata. Budapest: Typotex Kiadó – Eötvös Collegium. p. 221.

- ibn al-Awwam (ابن العوام), Abu Zakariya (أبو زكري) (1864). Kitab al fallah – le livre de l'Agriculture (in French). Paris: A. Franck.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Dodoens, Rembert (1554). Des Cruydboeks (in Dutch). Antwerp: J. van der Loe. pp. 128–131.

- Dodoens, Rembert (1553). Trium priorum de stirpium historia commentariorum imagines ad vivum expressae (in Latin). Antwerp: Jean de Loë. p. 132. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.7109.

- Dodoens, Rembert (1583). Stirpium historiae pemptades sex, sive libri XXX (in Latin). Antwerp: Christophori Plantini. p. 121. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.855.

- Bauhin, Gaspard (1596). Phytopinax, seu, Enumeratio plantarum ab herbariis nostro seculo descriptarum (in Latin). Basel: Sebastianum Henricpetri. p. 546. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.7115.

- Bauhin, Gaspard (1671). Caspari Bauhini Pinax Theatri botanici, sive Index in Theophrasti, Dioscoridis, Plinii et botanicorum qui à seculo scripserunt opera (in Latin) (2 ed.). Basel: Impensis Joannis Regis. p. 336. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.7092.

- Linnaeus, Carl (1753). Species Plantarum 2 (in Latin). Vol. 1. Stockholm: Lars Salvius. pp. 444–445.

- Burtt, B. L.; Lewis, Patricia (1954). "On the Flora of Kuweit: III". Kew Bulletin. 9 (3): 377–410. doi:10.2307/4108802. JSTOR 4108802.

- ICBN Vienna Code Art. 9.15; What this means is that the first authors who designated a lectotype do not have to be followed because their lectotype was not part of a single gathering.

- El Hadidi, M.N. (1993). in: Jarvis, C.E., Barrie, F.R., Allan, D.M. & Reveal, J.L., A List of Linnaean generic names and their types. Regnum Vegetabile 127: 74

- Peganum harmala in: The Linnaean Plant Name Typification Project, Natural History Museum, London

- "IPNI Plant Name Details". International Plant Names Index (IPNI). Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, Harvard University Herbaria, and Australian National Herbarium. 2015. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- "Peganum harmala var. grandiflorum Hadidi". GBIF Backbone Taxonomy, Checklist dataset (Data Set). GBIF Secretariat. 2017. doi:10.15468/39omei. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- "Peganum harmala var. multisecta Maxim". GBIF Backbone Taxonomy, Checklist dataset (Data Set). GBIF Secretariat. 2017. doi:10.15468/39omei. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- Maximovich, Carl Johann (1889). Flora tangutica sive Enumeratio plantarum regionis Tangut (Amdo) provinciae Kansu, nec non-Tibetiae praesertim orientaliborealis atque Tsaidam (in Russian). St. Petersburg: Academiae imperialis scientiarum petropolitanae. pp. 103–104. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.65520.

- "The Plant List: A Working List of all Plant Species".

- "Peganum multisectum (Maxim.) Bobrov". Tropicos. Missouri Botanical Garden. 2019. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- "Catalogue of Life China 2017 Annual Checklist". Biodiversity Committee, Chinese Academy of Sciences. 2017. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- Hassler, M. (November 2018). "World Plants: Synonymic Checklists of the Vascular Plants of the World". Species 2000 & ITIS Catalogue of Life, 20th February 2019. Catalogue of Life. Leiden: Naturalis. ISSN 2405-8858.

- "Peganum harmala var. stenophyllum Boiss". GBIF Backbone Taxonomy, Checklist dataset (Data Set). GBIF Secretariat. 2017. doi:10.15468/39omei. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- Alexanian, Kev (2007–2014). "AFRICAN RUE, Now That's What I Call A Weed!" (PDF). Central Oregonian. Crook County, Oregon. pp. 11–12. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- Alexanian, Kev (2007–2014). "CROOK COUNTY'S NOXIOUS WEED LIST, How We Got This Way" (PDF). Central Oregonian. Crook County, Oregon. pp. 113–114. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- Alexanian, Kev (2007–2014). "GRANTS A GO-GO, Got Weeds? There May Be Financial Help on the Horizon" (PDF). Central Oregonian. Crook County, Oregon. pp. 117–118. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- Bruneton, J. (2009). Pharmacognosie, Phytochimie, Plantes médicinales (in French) (4 ed.). Paris: Lavoisier.

- "Toxicity of Peganum harmala: Review and a Case Report - Iranian Journal of Pharmacology and Therapeutics". web.archive.org. 21 January 2022.

- Mabberley, D.J. (2008). Mabberley's Plant-book: A Portable Dictionary of Plants, Their Classifications, and Uses. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521820714.

- "Mordants". fortlewis.edu. Archived from the original on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- "Compilation: Peganum harmala". JSTOR: Global Plants. ITHAKA. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- "Herb Dictionary: apsand seed". Aunty Flo dot com herb-dictionary.

- "Kashmiri Rituals". ikashmir.net. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- Yiḥyah Salaḥ, Questions & Responsa Pe'ulath Ṣadiq, vol. I, responsum # 171, Jerusalem 1979; ibid., vol. III, responsum # 13 (Hebrew)

- Farouk L, Laroubi A, Aboufatima R, Benharref A, Chait A (February 2008). "Evaluation of the analgesic effect of alkaloid extract of Peganum harmala L.: possible mechanisms involved". J Ethnopharmacol. 115 (3): 449–54. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2007.10.014. PMID 18054186.

- Monsef, Hamid Reza; Ali Ghobadi; Mehrdad Iranshahi; Mohammad Abdollahi (19 February 2004). "Antinociceptive effects of Peganum harmala L. alkaloid extract on mouse formalin test" (PDF). J Pharm Pharmaceut Sci. 7 (1): 65–9. PMID 15144736. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- "MAPS – Pharmahuasca: On Phenethylamines and Potentiation". Archived from the original on 24 August 2007. Retrieved 16 August 2007.

- Zutshi, U.; Rao, P. G.; Soni, A.; Gupta, O. P.; Atal, C. K. (December 1980). "Absorption and distribution of vasicine a novel uterotonic". Planta Medica. 40 (4): 373–377. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1074988. ISSN 0032-0943. PMID 7220651.

- Panda H (2000). Herbs Cultivation and Medicinal Uses. Delhi: National Institute of Industrial Research. p. 435. ISBN 978-81-86623-46-6.

- DeKorne, Jim (2011). Psychedelic Shamanism, Updated Edition: The Cultivation, Preparation, and Shamanic Use of Psychotropic Plants. North Atlantic Books. pp. 154–155. ISBN 9781583942901.

- Hemmateenejad B, Abbaspour A, Maghami H, Miri R, Panjehshahin MR (August 2006). "Partial least squares-based multivariate spectral calibration method for simultaneous determination of beta-carboline derivatives in Peganum harmala seed extracts". Anal. Chim. Acta. 575 (2): 290–9. doi:10.1016/j.aca.2006.05.093. PMID 17723604.

- "Table 4 | Peganum spp.: A Comprehensive Review on Bioactivities and Health-Enhancing Effects and Their Potential for the Formulation of Functional Foods and Pharmaceutical Drugs". www.hindawi.com.

- Algorta, J; Pena, MA; Maraschiello, C; Alvarez-González, A; Maruhn, D; Windisch, M; Mucke, HA (March 2008). "Phase I clinical trial with desoxypeganine, a new cholinesterase and selective MAO-A inhibitor: tolerance and pharmacokinetics study of escalating single oral doses". Methods and Findings in Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology. 30 (2): 141–7. doi:10.1358/mf.2008.30.2.1159649. PMID 18560630.

- Pulpati H, Biradar YS, Rajani M (2008). "High-performance thin-layer chromatography densitometric method for the quantification of harmine, harmaline, vasicine, and vasicinone in Peganum harmala". J AOAC Int. 91 (5): 1179–85. doi:10.1093/jaoac/91.5.1179. PMID 18980138.

- Herraiz T, González D, Ancín-Azpilicueta C, Arán VJ, Guillén H (March 2010). "beta-Carboline alkaloids in Peganum harmala and inhibition of human monoamine oxidase (MAO)". Food Chem. Toxicol. 48 (3): 839–45. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2009.12.019. PMID 20036304.