Posthypnotic amnesia

Post-hypnotic amnesia is the inability in hypnotic subjects to recall events that took place while under hypnosis. This can be achieved by giving individuals a suggestion during hypnosis to forget certain material that they have learned either before or during hypnosis.[1] Individuals who are experiencing post-hypnotic amnesia cannot have their memories recovered once put back under hypnosis and is therefore not state dependent. Nevertheless, memories may return when presented with a pre-arranged cue. This makes post-hypnotic amnesia similar to psychogenic amnesia as it disrupts the retrieval process of memory.[2] It has been suggested that inconsistencies in methodologies used to study post-hypnotic amnesia cause varying results.[3]

History

Post-hypnotic amnesia was first discovered by Marquis de Puységur in 1784. When working with his subject Victor, Puységur noticed that when Victor would come out of hypnosis he would have amnesia for everything that had happened during the session. Recognizing the importance of this power, Puységur soon began treating those who were ill with induced amnesia. When French physician Ambroise-Auguste Liébeault published a book on hypnotism in 1866 he proposed that post-hypnotic amnesia was a "symptom" and a varying degree of hypnotism.[4] Similarly, 19th century French neurologist Jean Martin Charcot focused solely on post-hypnotic amnesia. Charcot introduced three states of hypnosis: fatigue, catalepsy, and somnambulism, or sleepwalking; it was within this last state that Charcot believed individuals could be communicated to and could respond to suggestions. Charcot showed that if an individual (through post-hypnotic suggestion) self-suggested that they had a psychological trauma, those who were neurologically susceptible would display symptoms of psychological trauma. It was hypothesized that this was due to the dissociation of the ideas from the rest of the individual's consciousness. However, dissociation theory was put aside for Freud's psychoanalytic theory and the rise of behaviourism until Ernest Hilgard renewed its study in the 1970s.[5]

Some of the earliest experimental studies on post-hypnotic amnesia were done by Clark Hull (1933). Hull's work showed that there was dissociation between explicit memory and implicit memory through studies on proactive interference and retroactive interference, pair associations and complex mental addition.[4]

In the mid-1960s, Evan and Thorn produced studies on source amnesia. In one study hypnotized individuals were taught answers to obscure facts and when brought out of their hypnotized states, one third of the individuals were able to produce the correct answers. Nevertheless, these same individuals had no conscious memory of where they learned this material.[6]

Categories

Spontaneous and suggested post-hypnotic amnesia can occur or be induced in an individual.

Spontaneous

For most of the 19th century, investigators reported that post-hypnotic amnesia only occurred spontaneously as scientific knowledge regarding this form of amnesia was minimal. Spontaneous post-hypnotic amnesia represents a slight memory impairment that results as a consequence of being put under hypnosis or being tested. This form of amnesia can also be experienced across susceptibility groups, but to a much lesser extent and magnitude to suggested post-hypnotic amnesia.[7]

Spontaneous amnesia has also been difficult to determine as research bias has been found to influence in many cases. In one study participants were put into two groups; one was to receive amnesic instructions and half were not given the instructions. The next day the groups were reversed. Results showed that there was little spontaneous amnesia across all participants, leading to doubts towards the actual occurrence of amnesia. It was later found that those more susceptible to hypnosis were more susceptible to suggested post-hypnotic amnesia and not spontaneous amnesia. These results suggest that spontaneous amnesia is less common than suggested amnesia and that when high results of spontaneous amnesia are recorded, some incidences may be false.[8]

Suggested

Suggested post-hypnotic amnesia involves the suggestion to hypnotized persons that following hypnosis they will be unable to accurately recall specific material (e.g. stimuli or events learned while under hypnosis) until they receive a reversibility cue.[9] This type of post-hypnotic amnesia is the most commonly used within research surrounding post-hypnotic amnesia due to its controlled nature.

Suggested amnesia has been found to result in a more significant memory loss than spontaneous amnesia, regardless of the order of induction. On average, more individuals experience suggested amnesia and there appears to be a moderate effect across individuals of all levels of hypnotic susceptibility.[7] Suggested post-hypnotic amnesia also involves a "temporary, retrieval-based dissociation between episodic and semantic memory".[1] However, it is more common for highly hypnotizable individuals to remember less information than low hypnotizable individuals or controls while under suggested post-hypnotic amnesia.[1]

Post-hypnotic amnesia is reversible, a characteristic that distinguishes it from other forms of amnesia that arise primarily from traumatic brain injury. Whereas the retrieval of memories under retrograde amnesia is a slow and labour-intensive process, the reversal of hypnotically-induced amnesia can occur with a simple suggestion or reversal cue (e.g., "when I clap my hands, you will remember everything").[10]

Types

Recall amnesia

Post-hypnotic recall amnesia refers to an individual's inability to recall, when in a normal conscious state, the events that occurred during hypnosis. Evidence for this type of post-hypnotic amnesia is seen in a typical research model testing where nonsense syllables, that were paired during hypnosis, are unable to be recalled post hypnotically when a suggestion for amnesia was given during hypnosis. Recall amnesia for word associations tend to be very high when done by post-hypnotic individuals, with some studies showing one hundred percent total recall amnesia.[11] This amnesia can also be measured by asking individuals, after their hypnosis has been terminated, to describe what they have been doing since they first laid down on the couch for their hypnosis session. When using this method for experimental testing, the hypnosis session will typically involve several tests or activities that the subject will engage in. Recall amnesia can then be measured by the amount of accurate tasks and activities the subject is able to remember.[12]

Recognition amnesia

Recognition amnesia equates to an impairment of an individual's recognition memory brought on by amnesia. As event-related potentials have been found to be sensitive to familiar stimuli in the absence of recognition impairments it has been suggested that individuals who report amnesia after hypnosis might not be experiencing post-amnesia recognition impairments. Instead, they may not be accurately describing their experience and confuse having amnesia for a lack of attention during encoding of tested stimuli.[13]

Source amnesia

Post-hypnotic source amnesia refers to the ability of individuals to correctly recall information learned during hypnosis without the recollection of where the information was acquired.[14] In a typical study examining this type of amnesia, individuals are administered a hypnotic induction procedure which is immediately followed by a series of questions concerning unfamiliar facts, for example "what year was Freud born in?". Subjects who are unable to correctly answer these questions are informed of the correct answers. These individuals are then administered a suggestion to be amnesic for everything that occurred during the period of which they are hypnotized. After the hypnotic session, those who exhibit post-hypnotic source amnesia, when asked the same unfamiliar questions again, will respond with the correct answers but will not be able to state where they learned the answer, or, more commonly, rationalize an incorrect source of their answer.[15]

Models and theoretical explanations

Dissociation

Dissociation, a theory originally applied by Pierre Janet, implies the view of the conscious self as being totally suspended. Dissociation, when referring to post-hypnotic amnesia, can be applied when the whole period in which an individual is hypnotized is looked at as an episode that is separated from the rest of that individual's experiences by boundaries of amnesia and suggestion. The failure to recall memory when in a normal, conscious state provides evidence to suggest that some kind of functional barrier is holding the information retained during hypnosis back from conscious recall. However, how sufficient the dissociative barrier in a hypnotic patient's mind is seems to be not all that effective, thus diminishing the credibility of the dissociation theory. This is easily seen in several studies where engaging in a secondary hypnotic session or the suggestion of the hypnotist or therapist to retrieve and recall information and events from the hypnotic session, readily and accurately initiate the retrieval that, according to dissociation, should be blocked from retrieval.[16]

Disrupted retrieval

This theory proposes that when it comes to post-hypnotic amnesia, individuals are unable to recall efficiently and accurately the events that took place while they were hypnotized because there is a greater degree of overall disruption in the retrieval of their hypnosis events. This temporary disruption in retrieval is typically due to the induced amnesic suggestion that a hypnotists or therapist will usually give during the session. Studies have been able to demonstrate this theory showing that hypnotizable subjects tend to recall events, if they even can, in a random, unassociated fashion, whereas subjects who did not receive a hypnotic suggestion for amnesia are able to recall in an orderly sequenced manner, starting with the original event of hypnosis and then recalling succeeding events in the correct order as they occurred. Results support this theory by indicating that effective retrieval cues, such as the temporal sequence of events, may not be being used successfully while under hypnosis compared to when they are used by individuals in a normal, waking state. As a result, a disruption in memory recollection which is characteristic of post-hypnotic amnesia appears.[17]

Verbal inhibition model

This theory on post-hypnotic amnesia argues that individuals who have been hypnotized actually do have the ability to remember material from their hypnosis sessions. However, these individuals simply inhibit their verbal report of that information.[18] It is believed that the material learned while under hypnosis is activated and retrieved into working memory where it is then processed and checked to see if it is material that can or should be remembered or if it is material that is forbidden and should therefore be forgotten. If the material is deemed forbidden, this theory suggests that the material is denied verbal output and sometimes even admission into an individual's conscious awareness.[19]

Effects and impact

Cognitive

Many theorists believe that explicit and implicit memory are separate memory systems in the brain. However, much research on explicit and implicit memory in post-hypnotic amnesia has shown that if they are separate areas, they interact often and in a variety of ways.[2] Attention, selection, and accessibility of information are processes thought to be involved in the phenomenon of posthypnotic amnesia, and when tested, post-hypnotic amnesia has shown to cause dissociation between both implicit and explicit expressions of memory.[13] In observing dissociation in post-hypnotic amnesia there are three aspects that differentiate it from other forms of amnesia. Firstly, items are deeply processed during encoding. Secondly, individuals are semantically primed – this relies on deep encoding and preserved cue retrieval. Thirdly, the impairment of the explicit memory is only temporary; implicit memories can be restored to explicit when given the reversible prearranged cue.[2] Research has found that the memory of individuals who are very highly susceptible to hypnotism is more influenced by implicit effects (word-stem completions, word associations and lexical decision tasks) than explicit effects (recognition tasks)[1] Those posthypnotic subjects who have no explicit memory of cues learned under hypnosis have been found to generate many of these explicit cues in free association tests.[2]

A post-hypnotic suggestion to forget can also successfully cause a deficit in autobiographical memory. Results from Barnier's study associating post-hypnotic amnesia and autobiographical supported previous findings regarding a dissociation between explicit and implicit memory, as well as impaired explicit recall – traits common to Psychogenic amnesia. After the suggested instructions to elicit post-hypnotic amnesia were administered, those participants that were highly susceptible to hypnosis showed more impaired recall of the autobiographical episode targeted by the suggestion, with both groups providing substantial information for the more recent autobiographical episode. Additionally, information from the "forgotten" episode (demonstrating implicit memory) influenced overall performance on the category-generation and social judgement tasks aimed at testing each participant's explicit memory.[9]

Biological

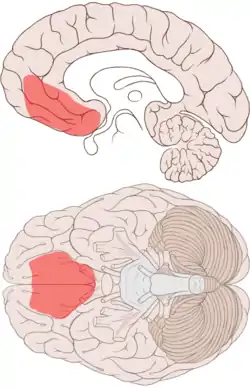

post-hypnotic amnesia is characterized as a "retrieval deficit", whereas other types of amnesia suffer from a "storage" deficit (e.g. Anterograde amnesia). post-hypnotic amnesia has been correlated with reduced cortical activity in the occipital and temporal cortex, while showing an increase in activation in the prefrontal cortex. It has been suggested that some of these areas are involved in the retrieval of long term episodic memories, while others are involved in inhibiting this retrieval. Various forms of functional amnesia have been suggested as the outcome of retrieval abortion and thus could be partially modeled using post-hypnotic amnesia (i.e. lower physical risk to the individual). For example, cases of post-hypnotic amnesia show strikingly similar cognitive and neurological characteristics to cases of functional amnesia. Previous fMRI studies indicate that individuals suffering from functional amnesia show reduced frontal lobe activity that could impair working memory and lexical tasks involving one's native language.[20]

The majority of what is understood on the neurological bases of post-hypnotic amnesia stems from an integral study completed by Mendelsohn et al. Two groups of participants viewed a narrative documentary. After one week participants were hypnotized while placed in an fMRI scanner and initiated into a suggestive post-hypnotic amnesia state where they were told to forget the details of the movie until they received a reversal cue. During scanning, participants were tested twice for their memory on either the movie details or context in which the movie was shown. These two test times allowed for the acquisition of brain activity "maps" during and after post-hypnotic amnesia had been lifted. Unlike in response to the Movie questions, the Context questions for both groups revealed several overlapping networks of activity, including visual, sensory and perceptual regions, the cerebellum, the parietal lobes, the superior frontal gyrus, and the inferior frontal gyrus. The post-hypnotic amnesia group showed reduced memory for the contents of the movie but not for context of viewing. These results identify specific circuits within the brain that regulate the suppression of long-term memory retrieval during post-hypnotic suggestion.[20]

Sociological

Post-hypnotic amnesia has been induced as a protective measure to help some individuals limit their recall of traumatic experiences. It can be used to limit the magnitude of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms (vivid memories and dreams), feelings of criminal victimization, the aftermath of natural disasters or the theory of UFO abductions. Suggested post-hypnotic amnesia can be induced and left for long periods of time, depending on if the amnesia is significant in reducing specific symptoms or memories, the content of the repressed material or the individual's motivation to recall events.[21]

The amount of scientific research on the effectiveness of hypnosis as a treatment for different types of pain (e.g. burns, cancer-related) is extensive. Landolt and Milling (2011) completed an exhaustive literature search that investigated the efficacy of hypnosis on reducing labor and delivery pain after pregnancy, in comparison to alternative interventions. They found that self-induced hypnosis was consistently more effective than standard medical care, counselling and education classes in relieving pain. However, this review did not include details on the effect of post-hypnotic amnesia on labor and delivery pain. This may be due to ethical barriers of inducing amnesia to individuals who are pregnant as they tend to be classified under "vulnerable" participant criteria.[22] Additionally, hypnotic suggestion has been used on specific conversion and psychiatric disorders to limit pain (e.g. limb paralysis, functional pain, auditory hallucinations and paranoid delusions of control). The use of hypnosis and suggestion for individuals with neurological disorders should be investigated more thoroughly to discern whether this potential treatment is of a generalized nature. Furthermore, the "experience" of hypnosis has consistently produced more accurate and realistic subjective reports than simply using one's imagination. Future research on this matter may lend support to subjects under hypnosis experiencing a greater "virtual reality" than control subjects and thus encourage practical, therapeutic applications in a clinical setting.[23]

The influence of hypnosis and amnesia has been present in the media for decades, with more television shows and movies involving the phenomenon than ever before. Some examples of these shows and movies include The Mentalist, Memento, 50 First Dates, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind and Captain Newman, M.D. The impact of post-hypnotic amnesia in the media has been far less successful, a result of the unique nature of the phenomenon, a general lack of knowledge on the subject or the idea that more the well-known and understood topics of hypnosis and amnesia can provide more creative vision and expansion. One unique exception is the band Post-Hypnotic Amnesia,[24] who seemed to understand enough of the phenomenon to dedicate it as their musical identity. Hypnosis in popular culture has more detailed listings of hypnosis in written works, film, television and online media.

Breaching

To induce post-hypnotic amnesia, subjects are told that they will not be able to remember anything that has happened during their hypnosis until the hypnotist later gives a cue saying that they can remember. There are various breaching procedures when it comes to post-hypnotic amnesia. One breaching procedure, initially done by Kenneth S. Bowers,[25] involved tricking participants into believing that the hypnosis experiment they were involved in had ended before the cue said to release their amnesia had been given. Subjects who were hypnotized were told that the experiment had media-recognition testing, also known as the experiential analysis technique has also been used to breach post-hypnotic amnesia. When given a video replay of a hypnosis session, subjects using the experiential analysis technique are asked to stop the video of their hypnosis session whenever they want to comment on their experiences. The video replay is typically shown before the amnesia during hypnosis is lifted, which, according to the experiential analysis technique, should cause the most inflexible and rigid hypnotic demands to breach.[26]

Criticisms

Three criticisms are commonly made about post-hypnotic amnesia. The first observes that those individuals who may have poorer memory retrieval in general will show higher incidences of post-hypnotic amnesia. Psychologist A.G. Hammer found that those who were poor at word associations in two successive tests were likely to be more amnesic in hypnosis experiments. The second recognizes that methodologies have been inconsistent across research, thus limiting the generalizability of findings.[8] Studies are often small and non-randomized, further limiting results. Finally, theories used in post-hypnotic amnesia have also been open to criticisms. Dissociation theory is criticized for its vague and inconsistent definition. Its ambiguousness has caused some to use the term when another mechanisms could be found to be the cause.[27]

The idea that hypnotic suggestion can be used to make individuals consent to acts that they would not normally have in a non-hypnotic state has been a criticism of suggested post-hypnotic amnesia for many years. A manipulative hypnotist may be able to convince a hypnotized person (e.g. a woman) that she is "unable to resist unwanted sexual suggestions" from the hypnotist. This idea poses the possibility of using hypnosis and suggested post-hypnotic amnesia for coercion, such that the woman may be induced into a state that limits her future recall of any negative experiences had at the hand of the hypnotist. However, most individuals cannot be forced to behave in a way that is against their will (this varies according to the suggestibility of the individual).[10]

The use of hypnosis in the military (see under "Military applications") has also been very controversial due to the idea that some soldiers may commit acts induced by hypnotic suggestion. However, many of the perceived "dangers" of hypnosis and post-hypnotic amnesia result from a lack of public education on the matter. For example, an interesting study conducted in 1964 involved the use of post-hypnotic amnesia to protect patients from the aftermath of "alien abductions". Following suggested post-hypnotic amnesia to a couple that had apparently experienced abduction by extraterrestrials, results indicate that the recalled memories may have actually been unconsciously influenced by the nightmares of one of the subjects, leading to more controversy on the matter of abductions and the reliability of suggested post-hypnotic amnesia procedures[21]

See also

- Amnesia

- False memory syndrome

- Hypnosis in popular culture

- Hypnotherapy

- Psychogenic amnesia

- Recovered memory therapy

- Retrograde amnesia

References

- Barnier, A., Bryant, R. A., & Briscoe, S. (2001). Posthypnotic amnesia for material learned before or during hypnosis: Explicit and implicit memory effects. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 49(4), 286–304.

- Kihlstrom, J.F. (1997). Hypnosis, memory and amnesia. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 352(1362), 1727–1732.

- Dorfman, J. & Kihlstrom, J. F. (1994). Semantic priming in post-hypnotic amnesia. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Psychonomic Society, St. Louis, November 1994.

- Hull, C.L. (1961). Hypnosis and suggestibility: An experimental approach. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Lynn, S. J., & Kirsch, I.,. (2006). In Steven Jay Lynn and Irving Kirsch. (Ed.), Essentials of clinical hypnosis an evidence-based approach / (1st ed. ed.) Washington, D.C. : American Psychological Association, c2006.

- Evans, F.J. & Thorn, W.A.F. (1963) Source amnesia after hypnosis. American Psychologist, 18, 373.

- Hilgard, E. R. & Cooper, L. M. (1965). Spontaneous and suggested posthypnotic amnesia. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 13(4), 261–273.

- Hilgard, E. R. (1966). Posthypnotic amnesia: Experiments and theory. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 14(2), 104–111.

- Barnier, A. J. (2002). Posthypnotic amnesia for autobiographical episodes: A laboratory model of functional amnesia? Psychological Science, 13(3), 232–237.

- Perry, C. Key concepts in hypnosis. False Memory Syndrome Foundation. Retrieved 12 March 2012 from http://www.fmsfonline.org/hypnosis.html#hdham2

- Evans, F.J., & Thorn, W.A.F. (1966). Two types of posthypnotic amnesia: Recall amnesia and source amnesia. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 14(2), 162–179.

- Williamsen, J. A., Johnson, H. J., & Eriksen, C. W. (1965). Some characteristics of posthypnotic amnesia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 70(2), 123–131.

- Allen, J. J., Iacono, W. G., Laravuso, J. J., & Dunn, L. A. (1995). An event-related potential investigation of posthypnotic recognition amnesia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 104(3), 421–430.

- Evans, F.J. (1979). "Contextual forgetting: Posthypnotic source amnesia". Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 88 (5): 556–563. doi:10.1037/0021-843x.88.5.556. PMID 500965.

- Spanos, P.N., Maxwell, I.G., Malva, D.L., & Bertrand, D.L. (1988). Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 97(3), 322–329.

- White, R. W., & Shevach, B. J. (1942). Hypnosis and the concept of dissociation. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 37(3), 309–328.

- Evans, F. J., & Kihlstrom, J. F. (1973). Posthypnotic amnesia as disrupted retrieval. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 82(2), 317–323.

- Coe, W. C. (1978). The credibility of post-hypnotic amnesia: A contextualist's view. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 26, 218–245.

- Huesmann, L. R., Gruder, C. L., & Dorst, G. (1987). A process model of posthypnotic amnesia. Cognitive Psychology, 19(1), 33–62.

- Mendelsohn, A., Chalamish, Y., Solomonovich, A., &Dudai, Y. (2008). Mesmerizing memories: brain substrates of episodic memory suppression in posthypnotic amnesia. Neuron, 57, 159–170.

- Marden, K. (2010). A primer on hypnosis. Retrieved from http://www.kathleen-marden.com/a-primer-on-hypnosis.php

- Landolt, A. S. & Milling, L. S. (2011). The efficacy of hypnosis as an intervention for labor and delivery pain: A comprehensive methodological review. Clinical Psychology Review, 31, 1022–1031.

- Oakley, D. A. & Halligan, P. W. (2009). Hypnotic suggestion and cognitive neuroscience. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(6), 264–270. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2009.03.004

- Posthypnotic Amnesia's Myspace page, http://www.myspace.com/phamnesia

- Bowers, K. S. (1966). Hypnotic behavior: The differentiation of trance and demand characteristic variables. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 71, 42–51.

- Coe, W. C., & Sluis, A. S. (1989). Increasing contextual pressures to breach posthypnotic amnesia. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(5), 885–894.

- Nash, M.R. & Barnier, A.J. (2008). The oxford handbook on hypnosis: Theory, research, and practice.Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.