Interphalangeal joints of the hand

The interphalangeal joints of the hand are the hinge joints between the phalanges of the fingers that provide flexion towards the palm of the hand.

| Joints of the hand | |

|---|---|

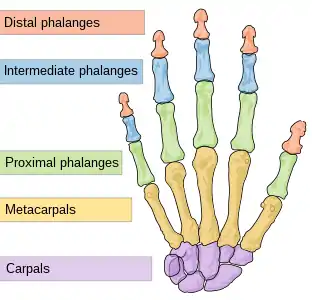

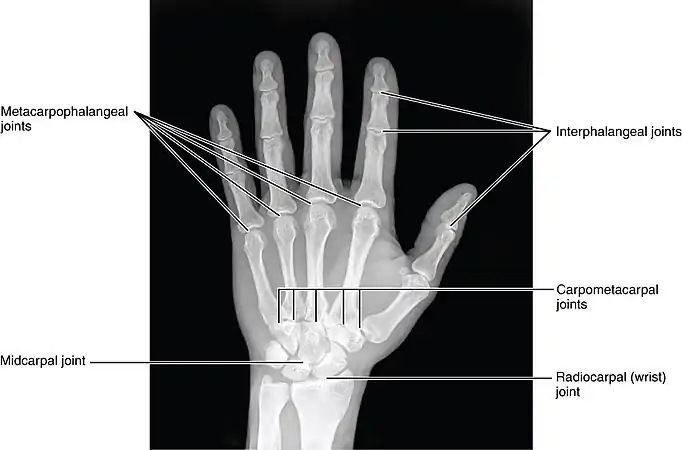

The DIP, PIP and MCP joints of the hand:

| |

Human hand bones | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | articulationes interphalangeae manus, articulationes digitorum manus |

| TA98 | A03.5.11.601 |

| TA2 | 1839 |

| FMA | 35285 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

There are two sets in each finger (except in the thumb, which has only one joint):

- "proximal interphalangeal joints" (PIJ or PIP), those between the first (also called proximal) and second (intermediate) phalanges

- "distal interphalangeal joints" (DIJ or DIP), those between the second (intermediate) and third (distal) phalanges

Anatomically, the proximal and distal interphalangeal joints are very similar. There are some minor differences in how the palmar plates are attached proximally and in the segmentation of the flexor tendon sheath, but the major differences are the smaller dimension and reduced mobility of the distal joint.[1]

Joint structure

The PIP joint exhibits great lateral stability. Its transverse diameter is greater than its antero-posterior diameter and its thick collateral ligaments are tight in all positions during flexion, contrary to those in the metacarpophalangeal joint.[1]

Dorsal structures

The capsule, extensor tendon, and skin are very thin and lax dorsally, allowing for both phalanx bones to flex more than 100° until the base of the middle phalanx makes contact with the condylar notch of the proximal phalanx.[1]

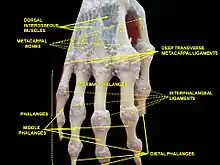

At the level of the PIP joint the extensor mechanism splits into three bands. The central slip attaches to the dorsal tubercle of the middle phalanx near the PIP joint. The pair of lateral bands, to which contribute the extensor tendons, continue past the PIP joint dorsally to the joint axis. These three bands are united by a transverse retinacular ligament, which runs from the palmar border of the lateral band to the flexor sheath at the level of the joint and which prevents dorsal displacement of that lateral band. On the palmar side of the joint axis of motion, lies the oblique retinacular ligament [of Landsmeer] which stretches from the flexor sheath over the proximal phalanx to the terminal extensor tendon. In extension, the oblique ligament prevents passive DIP flexion and PIP hyperextension as it tightens and pulls the terminal extensor tendon proximally.[2]

Palmar structures

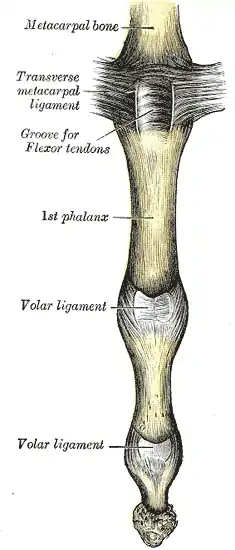

In contrast, on the palmar side, a thick ligament prevents hyperextension. The distal part of the palmar ligament, called the palmar plate, is 2 to 3 millimetres (0.079 to 0.118 in) thick and has a fibrocartilaginous structure. The presence of chondroitin and keratan sulfate in the dorsal and palmar plates is important in resisting compression forces against the condyles of the proximal phalanx. Together these structures protect the tendons passing in front and behind the joint. These tendons can sustain traction forces thanks to their collagen fibers.[1]

Palmar ligament

The palmar ligament is thinner and more flexible in its central-proximal part. On both sides it is reinforced by the so-called check rein ligaments. The accessory collateral ligaments (ACL) originate at the proximal phalanx and are inserted distally at the base of the middle phalanx below the collateral ligaments.[1]

The accessory ligament and the proximal margin of the palmar plate are flexible and fold back upon themselves during flexion. The flexor tendon sheaths are firmly attached to the proximal and middle phalanges by annular pulleys A2 and A4, while the A3 pulley and the proximal fibres of the C1 ligament attach the sheaths to the mobile volar ligament at the PIP joint. During flexion this arrangement produces a space at the neck of the proximal phalanx which is filled by the folding palmar plate.[2]

The palmar plate is supported by a ligament on either side of the joint called the collateral ligaments, which prevent deviation of the joint from side to side. The ligaments can partially or fully tear and can avulse with a small fracture fragment when the finger is forced backwards into hyperextension. This is called a "palmar plate, or volar plate injury".[3]

The palmar plate forms a semi-rigid floor and the collateral ligaments the walls in a mobile box which moves together with the distal part of the joint and provides stability to the joint during its entire range of motion. Because the palmar plate adheres to the flexor digitorum superficialis near the distal attachment of the muscle, it also increases the moment of flexor action. In the PIP joint, extension is more limited because of the two so called check-rein ligaments, which attach the palmar plate to the proximal phalanx.[2]

Movements

The only movements permitted in the interphalangeal joints are flexion and extension.

- Flexion is more extensive, about 100°, in the PIP joints and slightly more restricted, about 80°, in the DIP joints.

- Extension is limited by the volar and collateral ligaments.

The muscles generating these movements are:

| Location | Flexion | Extension |

|---|---|---|

| fingers | the flexor digitorum profundus acting on the proximal and distal joints, and the flexor digitorum superficialis acting on the proximal joints | mainly by the lumbricals and interossei, the long extensors having little or no action upon these joints |

| thumb | the flexor pollicis longus | the extensor pollicis longus |

The relative length of the digit varies during motion of the IP joints. The length of the palmar aspect decreases during flexion while the dorsal aspect increases by about 24 mm. The useful range of motion of the PIP joint is 30–70°, increasing from the index finger to the little finger. During maximum flexion the base of the middle phalanx is firmly pressed into the retrocondylar recess of the proximal phalanx, which provides maximum stability to the joint. The stability of the PIP joint is dependent of the tendons passing around it.[2]

Clinical significance

Rheumatoid arthritis generally spares the distal interphalangeal joints.[4] Therefore, arthritis of the distal interphalangeal joints strongly suggests the presence of osteoarthritis or psoriatic arthritis.[5]

References

- Lluch 1997, pp. 259–60

- Brüser & Gilbert 1999, pp. 158–60

- "Hand Therapy - Volar Plate Injury".

- Victoria Ruffing, Clifton O. Bingham. "Rheumatoid Arthritis Signs and Symptoms". Johns Hopkins Hospital. Retrieved 2017-08-10. Updated: April 4, 2017

- PJW Venables, Ravinder N Maini. "Diagnosis and differential diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis". UpToDate. Retrieved 2017-08-10. Last updated: Jan 22, 2016.

External links

Further reading

- Brüser, Peter; Gilbert, Alain (1999). Finger bone and joint injuries. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-85317-690-6.

- Lluch, Alberto (1997). "Interphalangeal joint anatomy". In Copeland, Stephen (ed.). Joint stiffness of the upper limb. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 1-85317-414-9.

![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 333 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 333 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)