Coelom

The coelom (or celom)[1] is the main body cavity in most animals[2] and is positioned inside the body to surround and contain the digestive tract and other organs. In some animals, it is lined with mesothelium. In other animals, such as molluscs, it remains undifferentiated. In the past, and for practical purposes, coelom characteristics have been used to classify bilaterian animal phyla into informal groups.

| Coelom | |

|---|---|

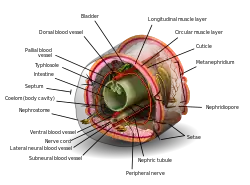

Cross-section of an oligochaete worm. The worm's body cavity surrounds the central typhlosole. | |

| Details | |

| Pronunciation | (/ˈsiːləm/ SEE-ləm, plural coeloms or coelomata /siːˈloʊmətə/ see-LOH-mə-tə) |

| Identifiers | |

| Greek | koilōma |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Etymology

The term coelom derives from the Ancient Greek word κοιλία (koilía), meaning 'cavity'.[3][4][5]

Structure

Development

The coelom is the mesodermally lined cavity between the gut and the outer body wall.

During the development of the embryo, coelom formation begins in the gastrulation stage. The developing digestive tube of an embryo forms as a blind pouch called the archenteron.

In Protostomes, the coelom forms by a process known as schizocoely.[6] The archenteron initially forms, and the mesoderm splits into two layers: the first attaches to the body wall or ectoderm, forming the parietal layer and the second surrounds the endoderm or alimentary canal forming the visceral layer. The space between the parietal layer and the visceral layer is known as the coelom or body cavity.

In Deuterostomes, the coelom forms by enterocoely.[6] The archenteron wall produces buds of mesoderm, and these mesodermal diverticula hollow to become the coelomic cavities. Deuterostomes are therefore known as enterocoelomates. Examples of deuterostome coelomates belong to three major clades: chordates (vertebrates, tunicates, and lancelets), echinoderms (starfish, sea urchins, sea cucumbers), and hemichordates (acorn worms and graptolites).

Origins

The evolutionary origin of the coelom is uncertain. The oldest known animal to have had a body cavity was the Vernanimalcula. Current hypothesis include:[7]

- The acoelomate theory, which states that coelom evolved from an acoelomate ancestor.

- The enterocoel theory, which states that coelom evolved from gastric pouches of cnidarian ancestors. This is supported by research on flatworms and small worms recently discovered in marine fauna ("coelom"[8]).

Functions

A coelom can absorb shock or provide a hydrostatic skeleton. It can also support an immune system in the form of coelomocytes that may either be attached to the wall of the coelom or may float about in it freely. The coelom allows muscles to grow independently of the body wall — this feature can be seen in the digestive tract of tardigrades (water bears) which is suspended within the body in the mesentery derived from a mesoderm-lined coelom.

Coelomic fluid

The fluid inside the coelom is known as coelomic fluid. This is circulated by mesothelial cilia or by contraction of muscles in the body wall which are themselves of mesin.[9] The coelomic fluid serves several functions: it acts as a hydroskeleton; it allows free movement and growth of internal organs; it serves for transport of gases, nutrients and waste products around the body; it allows storage of sperm and eggs during maturation; and it acts as a reservoir for waste.[10]

Classification in zoology

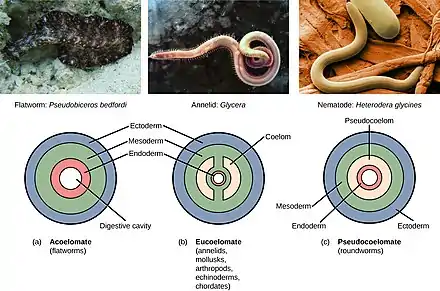

In the past, some zoologists grouped bilaterian animal phyla based on characteristics related to the coelom for practical purposes, knowing, and explicitly stating, that these groups were not phylogenetically related. Animals were classified in three informal groups according to the type of body cavity they possess, in a non-taxonomic, utilitarian way, as the Acoelomata, Pseudocoelomata, and Coelomata. These groups were never intended to represent related animals, or a sequence of evolutionary traits.

However, although this scheme was followed by a number of college textbooks and some general classifications, it is now almost totally abandoned as a formal classification. Indeed, as late as 2010, one author of a molecular phylogeny study mistakenly called this classification scheme the "traditional, morphology-based phylogeny".[11]

Coelomate animals or Coelomata (also known as eucoelomates – "true coelom") have a body cavity called a coelom with a complete lining called peritoneum derived from mesoderm (one of the three primary tissue layers). The complete mesoderm lining allows organs to be attached to each other so that they can be suspended in a particular order while still being able to move freely within the cavity. Most bilateral animals, including all the vertebrates, are coelomates.

Pseudocoelomate animals have a pseudocoelom (literally "false cavity"), which is a fluid filled body cavity. Tissue derived from mesoderm partly lines the fluid filled body cavity of these animals. Thus, although organs are held in place loosely, they are not as well organized as in a coelomate. All pseudocoelomates are protostomes; however, not all protostomes are pseudocoelomates. An example of a Pseudocoelomate is the roundworm. Pseudocoelomate animals are also referred to as Blastocoelomate.

Acoelomate animals, like flatworms, have no body cavity at all. Semi-solid mesodermal tissues between the gut and body wall hold their organs in place.

Coelomates

Coeloms developed in triploblasts but were subsequently lost in several lineages. The lack of a coelom is correlated with a reduction in body size. Coelom is sometimes incorrectly used to refer to any developed digestive tract. Some organisms may not possess a coelom or may have a false coelom (pseudocoelom). Animals having coeloms are called coelomates, and those without are called acoelomates. There are also subtypes of coelom:

- schizocoelom: develops from split in mesoderm found in annelids, arthropods and molluscs

- haemocoelom: true coelom reduced and cavity filled with blood found from arthropoda to mollusca

- enterocoelom: develops from wall of embryonic gut found from echinodermata to chordata

Coelomate phyla

According to Brusca and Brusca,[12] the following bilaterian phyla possess a coelom:

- Nemertea, traditionally viewed as acoelomates

- Priapulida

- Annelida

- Onychophora

- Tardigrada

- Arthropoda

- Mollusca

- Phoronida

- Ectoprocta

- Brachiopoda

- Echinodermata

- Chaetognatha

- Hemichordata

- Chordata

Pseudocoelomates

In some protostomes, the embryonic blastocoele persists as a body cavity. These protostomes have a fluid filled main body cavity unlined or partially lined with tissue derived from mesoderm.

This fluid-filled space surrounding the internal organs serves several functions like distribution of nutrients and removal of waste or supporting the body as a hydrostatic skeleton.

A pseudocoelomate or blastocoelomate is any invertebrate animal with a three-layered body and a pseudocoel. The coelom was apparently lost or reduced as a result of mutations in certain types of genes that affected early development. Thus, pseudocoelomates evolved from coelomates.[13] "Pseudocoelomate" is no longer considered a valid taxonomic group, since it is not monophyletic. However, it is still used as a descriptive term.

Important characteristics:

- lack a vascular blood system

- diffusion and osmosis circulate nutrients and waste products throughout the body.

- lack a skeleton

- hydrostatic pressure gives the body a supportive framework that acts as a skeleton.

- no segmentation

- body wall

- epidermis and muscle

- often syncytial

- usually covered by a secreted cuticle

- most are microscopic

- parasites of almost every form of life (although some are free living)

- eutely in some

- loss of larval stage in some

- possibly pedomorphism

Pseudocoelomate phyla

According to Brusca and Brusca,[12] bilaterian pseudocoelomate phyla include:

Some authors list the following phyla as pseudocoelomates:

Ecdysozoan pseudocoelomates

- Nematoda (roundworms)

- Nematomorpha (nematomorphs or horsehair worms)

- Loricifera

- Priapulida

- Kinorhyncha

Spiralian pseudocoelomates

- Gastrotricha

- Entoprocta

- Rotifera (rotifers)

- Acanthocephala (spiny-headed worms)

Acoelomates

Acoelomates lack a fluid-filled body cavity between the body wall and digestive tract. This can cause some serious disadvantages. Fluid compression is negligible, while the tissue surrounding the organs of these animals will compress. Therefore, acoelomate organs are not protected from crushing forces applied to the animal’s outer surface. The coelom can be used for diffusion of gases and metabolites etc. These creatures do not have this need, as the surface area to volume ratio is large enough to allow absorption of nutrients and gas exchange by diffusion alone, due to dorso-ventral flattening.

- Platyhelminthes

- Gastrotricha, traditionally viewed as blastocoelomates

- Entoprocta, traditionally viewed as blastocoelomates

- Gnathostomulida, traditionally viewed as blastocoelomates

- Cycliophora[14]

According to others, acoelomates include the cnidarians (jellyfish and allies), and the ctenophores (comb jellies), platyhelminthes (flatworms including tapeworms, etc.), Nemertea, and Gastrotricha.

See also

References

- "celom". Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

- "coelom" – via The Free Dictionary.

- Bailly, Anatole (1981-01-01). Abrégé du dictionnaire grec français. Paris: Hachette. ISBN 2010035283. OCLC 461974285.

- Bailly, Anatole. "Greek-french dictionary online". www.tabularium.be. Retrieved 2018-01-14.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 642.

- Lüter, Carsten (2000-06-01). "The origin of the coelom in Brachiopoda and its phylogenetic significance". Zoomorphology. 120 (1): 15–28. doi:10.1007/s004359900019. ISSN 1432-234X. S2CID 24929317.

- "Origins and Evolution of Animals". Archived from the original on 2018-11-12.

- "McGraw-Hill Dictionary of Scientific and Technical Terms". Answers.com. Archived from the original on 2014-12-20.

- Ruppert, Edward E.; Fox, Richard, S.; Barnes, Robert D. (2004). Invertebrate Zoology, 7th edition. Cengage Learning. p. 205. ISBN 978-81-315-0104-7.

- Dorit, R. L.; Walker, W. F.; Barnes, R. D. (1991). Zoology. Saunders College Publishing. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-03-030504-7.

- Nielsen, C. (2010). "The 'new phylogeny'. What is new about it?" Palaeodiversity 3, 149–150.

- R. C. Brusca, G. J. Brusca. Invertebrates. Sunderland, Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates, 2003 (2nd ed.), p. 47, ISBN 0-87893-097-3.

- Evers, Christine A., Lisa Starr. Biology:Concepts and Applications. 6th ed. United States:Thomson, 2006. ISBN 0-534-46224-3.

- R.C.Brusca, G.J.Brusca 2003, p. 379.

Further reading

- Dudek, Ronald W.; Fix, James D. (2004). "Body Cavities". Embryology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-5726-3.

- Hall, B.K.; et al. (2008). "Animals Based on Three Germ Layers and a Coelem". Strickberger's evolution: the integration of genes, organisms and populations. Jones & Bartlett Learning. ISBN 978-0-7637-0066-9.

- Overhill, Raith, ed. (2006). "What are the advantages of the coelem and metamarism?". An introduction to the invertebrates (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85736-9.