Cupriavidus metallidurans

Cupriavidus metallidurans is a non-spore-forming, Gram-negative bacterium which is adapted to survive several forms of heavy metal stress.[3][4][5]

| Cupriavidus metallidurans | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Binomial name | |

| Cupriavidus metallidurans (Goris et al. 2001) Vandamme and Coenye 2004 | |

| Type strain | |

| ATCC 43123, aka CH34 | |

| Synonyms | |

(Not distinguished from Ralstonia eutropha until 2001.)[2] | |

As a model and industrial system

It is an ideal subject to study heavy metal disturbance of cellular processes. This bacterium shows a unique combination of advantages not present in this form in other bacteria.

- Its genome (strain CH34) has been fully sequenced (preliminary, annotated sequence data were obtained from the DOE Joint Genome Institute)

- It is not pathogenic, therefore, models of the cell can also be tested in artificial environments similar to its natural habitats.

- It is related to the plant pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum.[6]

- It is of ecological importance since related bacteria are predominant in mesophilic heavy metal-contaminated environments.[2][7]

- It is of industrial importance and used for heavy metal remediation and sensing.[4]

- It is an aerobic chemolithoautotroph, facultatively able to grow in a mineral salts medium in the presence of H2, O2, and CO2 without an organic carbon source.[8] The energy-providing subsystem of the cell under these conditions is composed only of the hydrogenase, the respiratory chain, and the F1F0-ATPase. This keeps this subsystem simple and clearly separated from the anabolic subsystems that starts with the Calvin cycle for CO2-fixation.

- It is able to degrade xenobiotics even in the presence of high heavy metal concentrations.[9]

- Finally, strain CH34 is adapted to the outlined harsh conditions by a multitude of heavy-metal resistance systems that are encoded by the two indigenous megaplasmids pMOL28 and pMOL30 on the bacterial chromosome(s).[3][4][10]

Ecology

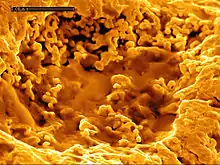

A scanning electron microscope image of a gold nugget, revealing bacterioform (bacteria-shaped) structures

C. metallidurans plays a vital role, together with Delftia acidovorans, in the formation of gold nuggets. It precipitates metallic gold from a solution of gold(III) chloride, a compound highly toxic to most other microorganisms.[11][12][13]

References

- Vandamme, P.; T. Coeyne (June 18, 2004). "Taxonomy of the genus Cupriavidus: a tale of lost and found". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 54 (Pt 6): 2285–2289. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.63247-0. PMID 15545472.

- Goris, J.; et al. (2001). "Classification of metal-resistant bacteria from industrial biotopes as Ralstonia campinensis sp. nov., Ralstonia metallidurans sp. nov. and Ralstonia basilensis Steinle et al. 1998 emend". Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 51 (Pt 5): 1773–1782. doi:10.1099/00207713-51-5-1773. PMID 11594608.

- Nies, DH (1999). "Microbial heavy metal resistance". Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 51 (6): 730–750. doi:10.1007/s002530051457. PMID 10422221. S2CID 6675586.

- Nies, DH (2000). "Heavy metal resistant bacteria as extremophiles: molecular physiology and biotechnological use of Ralstonia spec. CH34". Extremophiles. 4 (2): 77–82. doi:10.1007/s007920050140. PMID 10805561. S2CID 11156112.

- Ryan, Michael P.; Adley, Catherine C. (2011-09-01). "Specific PCR to identify the heavy-metal-resistant bacterium Cupriavidus metallidurans". Journal of Industrial Microbiology & Biotechnology. 38 (9): 1613–1615. doi:10.1007/s10295-011-1011-y. ISSN 1476-5535. PMID 21720772. S2CID 33552248.

- Salanoubat M.; et al. (2002). "Genome sequence of the plant pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum". Nature. 415 (6871): 497–502. doi:10.1038/415497a. PMID 11823852.

- Diels, L.; Q. Dong; D. van der Lelie; W. Baeyens; M. Mergeay (1995). "The czc operon of Alcaligenes eutrophus CH34: from resistance mechanism to the removal of heavy metals". Journal of Industrial Microbiology. 14 (2): 142–153. doi:10.1007/BF01569896. PMID 7766206. S2CID 29272445.

- Mergeay, M.; D. Nies; H.G. Schlegel; J. Gerits; P. Charles; F. van Gijsegem (1985). "Alcaligenes eutrophus CH34 is a facultative chemolithotroph with plasmid-bound resistance to heavy metals". Journal of Bacteriology. 162 (1): 328–334. doi:10.1128/JB.162.1.328-334.1985. PMC 218993. PMID 3884593.

- Springael, D.; L. Diels; L. Hooyberghs; S. Kreps; M. Mergeay (1993). "Construction and characterization of heavy metal resistant haloaromatic-degrading Alcaligenes eutrophus strains". Appl Environ Microbiol. 59 (1): 334–339. doi:10.1128/AEM.59.1.334-339.1993. PMC 202101. PMID 8439161.

- Monchy, S.; M.A. Benotmane; P. Janssen; T. Vallaeys; S. Taghavi; D. van der Lelie; M. Mergeay (October 2007). "Plasmids pMOL28 and pMOL30 of Cupriavidus metallidurans are specialized in the maximal viable response to heavy metals". Journal of Bacteriology. 189 (20): 7417–7425. doi:10.1128/JB.00375-07. PMC 2168447. PMID 17675385.

- Reith, Frank; Stephen L. Rogers; D. C. McPhail; Daryl Webb (July 14, 2006). "Biomineralization of Gold: Biofilms on Bacterioform Gold". Science. 313 (5784): 233–236. Bibcode:2006Sci...313..233R. doi:10.1126/science.1125878. hdl:1885/28682. PMID 16840703. S2CID 32848104.

- Superman-Strength Bacteria Produce 24-Karat Gold

- The bacteria that turns toxic chemicals into pure gold

External links

This article is issued from Wikipedia. The text is licensed under Creative Commons - Attribution - Sharealike. Additional terms may apply for the media files.