RICE (medicine)

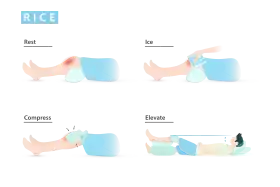

RICE is a mnemonic acronym for four elements of treatment for soft tissue injuries: rest, ice, compression, and elevation.[1][2][3] RICE is considered a first-aid treatment rather than a cure for soft-tissue injuries. The aim is to manage discomfort.[4]

| RICE | |

|---|---|

|

The mnemonic was introduced by Gabe Mirkin in 1978.[5] He has since recanted his support for the regimen. In 2014 he wrote:[6]

Coaches have used my 'RICE' guideline for decades, but now it appears that both ice and complete rest may delay healing, instead of helping. In a recent study, athletes were told to exercise so intensely that they developed severe muscle damage that caused extensive muscle soreness. Although cooling delayed swelling, it did not hasten recovery from this muscle damage.

There is not enough evidence to determine the effectiveness of RICE therapy for acute ankle sprains. Treatment decisions for ankle sprains must be made on an individual basis and relies on expert opinions and national guidelines.[7] The cold or ice component of RICE and its variations reduces blood flow to the injured area and delays healing.[8]

Primary four terms

Rest

Rest is a key component of repairing the body. Without rest, continual strain is placed on the affected area, leading to increased inflammation, pain, and possible further injury. Rest is recommended during the initial 24–48 hours after an injury, but after that modified activities can be started.[9] Additionally, some soft tissue injuries will take longer to heal without rest. There is also a risk of abnormal repair or chronic inflammation resulting from a failure to rest. In general, the period of rest should be long enough that the patient is able to use the affected limb with the majority of function restored and pain essentially gone.

Ice

In 2015, Gabe Mirkin, the doctor who initially coined the term R.I.C.E in his 1978 book "The sports medicine book", has eliminated his recommendation for ice except within the first six hours since injury to reduce pain, as it has since been shown to reduce healing. The inflammation is reduced due to a decrease in leukocytes and granulocytes and the restriction of macrophage infiltration. These physiological changes can slow down the healing process. Typically, when the body detects an injury, it sends a message to the inflammatory cells (macrophages) to produce growth factor (IGF-1). This kills the damaged tissue, resulting in healing. However, ice causes vasoconstriction when applied. This prevents the transport of inflammatory cells and chemicals. If IGF-1 cannot get to the site of injury, the healing process can be delayed, or even inhibited[10][11].[12][13]

Even more, studies have found a significant decrease in one's capability to reproduce knee joint flexion in the sagittal plane and causes a lack of varus control leading to a valgus shift in the frontal plane during eccentric contraction after the use of cryotherapy.[14]

There is no definitive evidence that ice is effective or ineffective. But evidence does show that ice can be used as an adjunct to therapeutic rehabilitation in that ice helps reduce localized pain.[15] A combination of cryotherapy followed by exercise saw the best result in strength gain.[16] Exceeding the recommended time for ice application may be detrimental, as it has been shown to delay healing.

Ice reduces the inflammatory response and pain associated with heat generated by increased blood flow and/or blood loss.[17] A good method is apply ice for 20 minutes of each hour. Other recommendations are an alternation of ice and no-ice for 15–20 minutes each, for a period of 48 to 72 hours, and then apply heat if swelling is gone. It is recommended that the ice or heat pack be placed within a towel or other insulating material before wrapping around the area.[18]

Compression

Compression stockings or sleeves are a viable option to manage swelling of extremities with graduated compression (where the amount of compression decreases as the distance to the heart decreases). These garments are especially effective post-operatively and are used in virtually all hospitals to manage acute or chronic swelling, such as congestive heart failure. An elastic bandage, rather than a firm plastic bandage (such as zinc-oxide tape) is required. Usage of a tight, non-elastic bandage will result in reduction of adequate blood flow, potentially causing ischemia. The fit should be snug so as to not move freely, but still allow expansion for when muscles contract and fill with blood.

Compression aims to reduce the edematous swelling that results from the inflammatory process. Although some swelling is inevitable, too much swelling results in significant loss of function, excessive pain and eventual slowing of blood flow through vessel restriction.

Elevation

Elevation aims to reduce swelling by increasing venous return of blood to the systemic circulation. This will result in less edema which reduces pain and/or swelling.

Variations

Variations of the acronym are sometimes used, to emphasize additional steps that should be taken. These include:

- "RICE" - Rest, Immobilize, Cold, Elevate[19]

- "HI-RICE" – Hydration, Ibuprofen, Rest, Ice, Compression, and Elevation

- "PRICE" – Protection, Rest, Ice, Compression, and Elevation[20][21][22]

- "PRICE" – Pulse (Typically Radial or Distal), Rest, Ice, Compression, and Elevation

- "PRICES" – Protection, Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation, and Support

- "PRINCE" – Protection, Rest, Ice, NSAIDs, Compression, and Elevation[23]

- "RICER" – Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation, and Referral[24]

- "DRICE" – Diagnosis, Rest, Ice, Compression, and Elevation

- "POLICE" – Protection, Optimal Loading, Ice, Compression, and Elevation[25]

See also

References

- "R.I.C.E - Best for Acute Injuries". Retrieved 15 August 2007.

- "Sports Medicine Advisor 2005.4: RICE: Rest, Ice, Compression, and Elevation for Injuries". Archived from the original on 11 September 2007. Retrieved 15 August 2007.

- MedicalMnemonics.com: 235

- Järvinen TA, Järvinen TL, Kääriäinen M, et al. (2007). "Muscle injuries: optimising recovery". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Rheumatology. 21 (2): 317–31. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2006.12.004. PMID 17512485.

- Sportsmedicine (ISBN 978-0316574365)

- "Why Ice Delays Recovery". Archived from the original on 29 June 2014. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- van den Bekerom MP, Struijs PA, Blankevoort L, Welling L, van Dijk CN, Kerkhoffs GM (2012). "What is the evidence for rest, ice, compression, and elevation therapy in the treatment of ankle sprains in adults?". Journal of Athletic Training. 47 (4): 435–43. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-47.4.14. PMC 3396304. PMID 22889660.

- "Why You Should Avoid Ice for a Sprained Ankle". Consumer Reports. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- "Physiotherapy". Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- Wang, Zi-Ru; Ni, Guo-Xin (16 June 2021). "Is it time to put traditional cold therapy in rehabilitation of soft-tissue injuries out to pasture?". World Journal of Clinical Cases. 9 (17): 4116–4122. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v9.i17.4116. PMC 8173427. PMID 34141774.

- Wang, Zi-Ru; Ni, Guo-Xin (16 June 2021). "Is it time to put traditional cold therapy in rehabilitation of soft-tissue injuries out to pasture?". World Journal of Clinical Cases. 9 (17): 4116–4122. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v9.i17.4116. ISSN 2307-8960. PMC 8173427. PMID 34141774.

- Why Ice Delays Recovery

- Bleakley C, McDonough S, MacAuley D (1 January 2004). "The Use of Ice in the Treatment of Acute Soft-Tissue Injury: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 32 (1): 251–261. doi:10.1177/0363546503260757. ISSN 0363-5465. PMID 14754753. S2CID 23999521.

- Alexander, Jill; Selfe, James; Oliver, Ben; Mee, Daniel; Carter, Alexandra; Scott, Michelle; Richards, Jim; May, Karen (2016). "An exploratory study into the effects of a 20 minute crushed ice application on knee joint position sense during a small knee bend". Physical Therapy in Sport. 18: 21–26. doi:10.1016/j.ptsp.2015.06.004. PMID 26822165. S2CID 22022502. ProQuest 1768612124.

- Yu, Shi-yang; Chen, Shuai; Yan, He-de; Fan, Cun-yi (January 2015). "Effect of cryotherapy after elbow arthrolysis: a prospective, single-blinded, randomized controlled study". Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 96 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2014.08.011. ISSN 1532-821X. PMID 25194452.

- Hart, Joseph M.; Kuenze, Christopher M.; Diduch, David R.; Ingersoll, Christopher D. (1 December 2014). "Quadriceps Muscle Function After Rehabilitation With Cryotherapy in Patients With Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction". Journal of Athletic Training. 49 (6): 733–739. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-49.3.39. ISSN 1062-6050. PMC 4264644. PMID 25299442.

- "Sprains and strains". Archived from the original on 17 March 2009.

- RICE: Rest, Ice, Compression, and Elevation for Injuries on the website of the University of Michigan Health System, Retrieved 28 July 2008

- American Red Cross (20 September 2012). "For sprains remember RICE". Twitter. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

For sprains remember RICE: Rest, Immobilize, Cold, Elevate. Get First Aid #gameplan tips with our free app: http://rdcrss.org/SpSy0a

{{cite web}}: External link in|quote= - "Sprains and strains: Self-care - MayoClinic.com". Retrieved 15 August 2007.

- Ivins D (2006). "Acute ankle sprain: an update". American Family Physician. 74 (10): 1714–20. PMID 17137000.

- Bleakley CM, O'Connor S, Tully MA, Rocke LG, Macauley DC, McDonough SM (2007). "The PRICE study (Protection Rest Ice Compression Elevation): design of a randomised controlled trial comparing standard versus cryokinetic ice applications in the management of acute ankle sprain [ISRCTN13903946]". BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 8: 125. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-8-125. PMC 2228299. PMID 18093299.

- "Ankle sprain - Yahoo! Health". Retrieved 23 February 2008.

- "SmartPlay : Managing your Injuries". Retrieved 28 May 2008.

- C M, Bleakley (2012). "PRICE needs updating, should we call the POLICE?". British Journal of Sports Medicine. BMJ. 46 (4): 220–221. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2011-090297. PMID 21903616. S2CID 41536790. Retrieved 5 March 2012.