Bone age

Bone age is the degree of maturation of a child's bones. As a person grows from fetal life through childhood, puberty, and finishes growth as a young adult, the bones of the skeleton change in size and shape. These changes can be seen by x-ray techniques. The "bone age" of a child is the average age at which children reach various stages of bone maturation. A child's current height and bone age can be used to predict adult height. For most people, their bone age is the same as their biological age but for some individuals, their bone age is a couple of years older or younger. Those with advanced bone ages typically hit a growth spurt early on but stop growing sooner, while those with delayed bone ages hit their growth spurt later than normal. Children who are below average height do not necessarily have a delayed bone age; in fact their bone age could actually be advanced which if left untreated, will stunt their growth.

At birth, only the metaphyses of the "long bones" are present. The long bones are those that grow primarily by elongation at an epiphysis at one end of the growing bone. The long bones include the femurs, tibias, and fibulas of the lower limb, the humeri, radii, and ulnas of the upper limb (arm + forearm), and the phalanges of the fingers and toes. The long bones of the leg comprise nearly half of adult height. The other primary skeletal component of height is the spine and skull.

As a child grows the epiphyses become calcified and appear on the x-rays, as do the carpal and tarsal bones of the hands and feet, separated on the x-rays by a layer of invisible cartilage where most of the growth is occurring. As sex steroid levels rise during puberty, bone maturation accelerates. As growth nears conclusion and attainment of adult height, bones begin to approach the size and shape of adult bones. The remaining cartilaginous portions of the epiphyses become thinner. As these cartilaginous zones become obliterated, the epiphyses are said to be "closed" and no further lengthening of the bones will occur. A small amount of spinal growth concludes an adolescent's growth.

Pediatric endocrinologists frequently order bone age x-rays to evaluate children for advanced or delayed growth and physical development. These are interpreted by pediatric radiologists, physicians who are experts in using medical imaging for pediatric diagnosis and therapy.

Methods

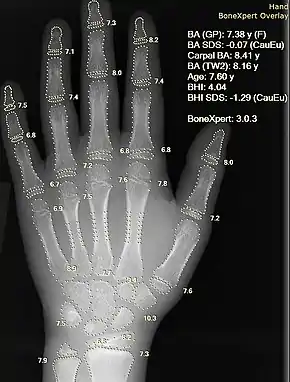

The most commonly used method of determining bone age is based on a single x-ray of the left hand, fingers, and wrist. A hand is easily x-rayed with minimal radiation [1] and shows many bones in a single view.[2] The bones in the x-ray are compared to the bones of a standard atlas, usually "Greulich and Pyle".[3][4]

A more complex method also based on hand x-rays is the "TW2"[5] or the "TW3"[6] method (TW = Tanner Whitehouse) method.

An atlas based on knee maturation has also been compiled.[7]

The hands of infants do not change much in the first year of life and if precise bone age assessment is desired, an x-ray of approximately half of the skeleton (a "hemiskeleton" view) may be obtained to assess some of the areas such as shoulders and pelvis which change more in infancy.

Lamparski (1972)[8] used the cervical vertebrae and found them to be as reliable and valid as the hand-wrist area for assessing skeletal age. He developed a series of standards for assessment of skeletal age for both males and females. This method has the advantage of eliminating the need for an additional radiographic exposure since the vertebrae are already recorded on the lateral cephalometric radiographic.

Hassel & Farman (1995)[9] developed an index based on the second, third, and fourth cervical vertebrae (C2, C3, C4) and proved that atlas maturation was highly correlated with skeletal maturation of the hand-wrist. Several smartphone applications have been developed to facilitate the use of vertebral methods such as Easy Age.

Height prediction

Statistics have been compiled to indicate the percentage of height growth remaining at a given bone age. By simple arithmetic, a predicted adult height can be computed from a child's height and bone age. Separate tables are used for boys and girls because of the sex difference in timing of puberty, and slightly different percentages are used for children with unusually advanced or delayed bone maturation. These tables, the Bayley-Pinneau tables, are included as an appendix in the Greulich and Pyle atlas.

In a number of conditions involving atypical growth, bone age height predictions are less accurate. For example, in children born small for gestational age who remain short after birth, the bone age is a poor predictor of adult height.[10]

Clinical application of bone age readings

For the average person with average puberty, the bone age would match the person's chronological age. In terms of height growth and height growth related to bone age, average females stop growing taller two years earlier than average males. Peak height velocity (PHV) occurs at the average age of 11 years for girls and at the average age of 13 years for boys.[11] A girl has reached 99% of her adult height at a bone age of 15 years and has a small amount of height growth left from this point on. A boy has reached 99% of his adult height at a bone age of 17 years and has a small amount of height growth left from this point on. When the bone age reaches 16 years in females and 18 years in males, growth in height is over and they have reached their full adult height.[12][13][14][15][16]

There are exceptions with people who have an advanced bone age (bone age is older than chronological age) due to being an early bloomer (someone starting puberty and hitting PHV earlier than average), being an early bloomer with precocious puberty, or having another condition. There are also exceptions with people who have a delayed bone age (bone age is younger than chronological age) due to being a late bloomer (someone starting puberty and hitting PHV later than average), being a late bloomer with delayed puberty, or having another condition.[17]

An advanced or delayed bone age does not always indicate disease or "pathologic" growth. Conversely, the bone age may be normal in some conditions of abnormal growth. Children do not mature at exactly the same time. Just as there is wide variation among the normal population in age of losing teeth or experiencing the first menstrual period, the bone age of a healthy child may be a year or two advanced or delayed. Those with an advanced bone age typically hit a growth spurt early on but stop growing at an earlier age. Consequently, when a naturally short child has an advanced bone age, it stunts their growth at an early age leaving them even shorter than they would have been. Because of this, those who are short with an advanced bone age, need medical attention before their bones fully fuse.

An advanced bone age is common when a child has had prolonged elevation of sex steroid levels, as in precocious puberty or congenital adrenal hyperplasia. The bone age is often marginally advanced with premature adrenarche, when a child is overweight from a young age or when a child has lipodystrophy. Those with an advanced bone age typically hit a growth spurt early on but stop growing at an earlier age. Bone age may be significantly advanced in genetic overgrowth syndromes, such as Sotos syndrome, Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome and Marshall-Smith syndrome.[18]

Bone maturation is delayed with the variation of normal development termed Constitutional delay of growth and puberty, but delay also accompanies growth failure due to growth hormone deficiency and hypothyroidism.[19]

Recent studies show that organs like liver can also be used to estimate age and sex, because of the unique feature of liver.[20] Liver weight increases with age and is different between males and females. Thus, liver can be employed in special medico-legal cases of skeletal deformities or mutilation.

References

- Patcas, R.; Signorelli, L.; Peltomaki, T.; Schatzle, M. (2012). "Is the use of the cervical vertebrae maturation method justified to determine skeletal age? A comparison of radiation dose of two strategies for skeletal age estimation". The European Journal of Orthodontics. 35 (5): 604–9. doi:10.1093/ejo/cjs043. PMID 22828078.

- Gertych, A.; Zhang, A.; Sayre, J.; Pospiechkurkowska, S.; Huang, H. (Jun–Jul 2007). "Bone age assessment of children using a digital hand atlas". Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics. 31 (4–5): 322–331. doi:10.1016/j.compmedimag.2007.02.012. PMC 1978493. PMID 17387000.

- Büken, B.; Şafak, A. A.; Yazıcı, B.; Büken, E.; Mayda, A. S. (Dec 2007). "Is the assessment of bone age by the Greulich–Pyle method reliable at forensic age estimation for Turkish children?". Forensic Science International. 173 (2–3): 146–153. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2007.02.023. PMID 17391883.

- Greulich WW, Pyle SI: Radiographic Atlas of Skeletal Development of the Hand and Wrist, 2nd edition. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1959.

- Tanner JM, Whitehouse RH, Marshall WA, et al.: Assessment of Skeletal Maturity and Prediction of Adult Height (TW2 Method). New York: Academic Press, 1975.

- Sanctis, VincenzoDe; Maio, SalvatoreDi; Soliman, AshrafT; Raiola, Giuseppe; Elalaily, Rania; Millimaggi, Giuseppe (2014). "Hand X-ray in pediatric endocrinology: Skeletal age assessment and beyond". Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 18 (7): S63–S71. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.145076. ISSN 2230-8210. PMC 4266871. PMID 25538880.

- Poznanski, Andrew (January 1978). "Book Review: Skeletal Maturity. The Knee Joint as a Biological Indicator". Radiology. 126 (1). doi:10.1148/126.1.88. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- Lamparski, DG (1972). "Skeletal Age Assessment Utilizing Cervical Vertebrae". Master Science Thesis.

- Hassel, B.; Farman, A. G. (January 1995). "Skeletal maturation evaluation using cervical vertebrae". American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. 107 (1): 58–66. doi:10.1016/S0889-5406(95)70157-5. ISSN 0889-5406. PMID 7817962.

- Clayton, P.E.; Cianfarani, S.; Czernichow, P.; Johannsson, G.; Rapaport, R.; Rogol, A. (2007). "Management of the Child Born Small for Gestational Age through to Adulthood: A Consensus Statement of the International Societies of Pediatric Endocrinology and the Growth Hormone Research Society". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 92 (3): 804–810. doi:10.1210/jc.2006-2017. PMID 17200164.

- Walker, Owen. "PEAK HEIGHT VELOCITY". Science for Sport. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- Khadilkar, Vaman (6 February 2019). IAP Textbook On Pediatric Endocrinology. ISBN 9789352709052. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- Strauss, Barbieri (13 September 2013). Yen and Jaffe's Reproductive Endocrinology. ISBN 9781455727582. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- "2 to 20 years: Girls Stature-for-age and Weight-for-age percentiles" (PDF). CDC. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- "2 to 20 years: Boys Stature-for-age and Weight-for-age percentiles" (PDF). CDC. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- "Physical Development, Ages 11 to 14 Years". HealthlinkBc. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- Flor-Cisneros, Armando; Roemmich, James N.; Rogol, Alan D.; Baron, Jeffrey (July 2006). "Bone age and onset of puberty in normal boys". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 254–255: 202–206. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2006.04.008. PMC 1586226. PMID 16837127.

- Manor, Joshua; Lalani, Seema R. (30 October 2020). "Overgrowth Syndromes—Evaluation, Diagnosis, and Management". Frontiers in Pediatrics. 8: 574857. doi:10.3389/fped.2020.574857.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Soliman, AshrafT; Sanctis, VincenzoDe (2012). "An approach to constitutional delay of growth and puberty". Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 16 (5): 698. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.100650.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Das S, Ghosh R, Chowdhuri S. A novel approach to estimate age and sex from mri measurement of liver dimensions in an Indian (Bengali) Population – A pilot study. J Forensic Sci Med [serial online] 2019 [cited 2020 Jan 31];5:177-80. Available from: http://www.jfsmonline.com/text.asp?2019/5/4/177/272723