Wound

A wound is a rapid onset of injury that involves lacerated or punctured skin (an open wound), or a contusion (a closed wound) from blunt force trauma or compression. In pathology, a wound is an acute injury that damages the epidermis of the skin. To heal a wound, the body undertakes a series of actions collectively known as the wound healing process.

| Wound | |

|---|---|

| |

| Wounds on a male torso | |

| Specialty | Emergency medicine Plastic Surgery |

Classification

According to level of contamination, a wound can be classified as:

- Clean wound – made under sterile conditions where there are no organisms present, and the skin is likely to heal without complications.

- Contaminated wound – usually resulting from accidental injury; there are pathogenic organisms and foreign bodies in the wound.

- Infected wound – the wound has pathogenic organisms present and multiplying, exhibiting clinical signs of infection (yellow appearance, soreness, redness, oozing pus).

- Colonized wound – a chronic situation, containing pathogenic organisms, difficult to heal (e.g. bedsore).

Open

Open wounds can be classified according to the object that caused the wound:

- Incisions or incised wounds – caused by a clean, sharp-edged object such as a knife, razor, or glass splinter.

- Lacerations – irregular tear-like wounds caused by some blunt trauma. Lacerations and incisions may appear linear (regular) or stellate (irregular). The term laceration is commonly misused in reference to incisions.[1]

- Abrasions (grazes) – superficial wounds in which the topmost layer of the skin (the epidermis) is scraped off. Abrasions are often caused by a sliding fall onto a rough surface such as asphalt, tree bark or concrete.

- Avulsions – injuries in which a body structure is forcibly detached from its normal point of insertion. A type of amputation where the extremity is pulled off rather than cut off. When used in reference to skin avulsions, the term 'degloving' is also sometimes used as a synonym.

- Puncture wounds – caused by an object puncturing the skin, such as a splinter, nail or needle.

- Penetration wounds – caused by an object such as a knife entering and coming out from the skin.

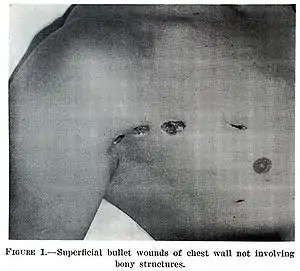

- Gunshot wounds – caused by a bullet or similar projectile driving into or through the body. There may be two wounds, one at the site of entry and one at the site of exit, generally referred to as a "through-and-through."

- Critical wounds- Including large burns that have been split. These wounds can cause serious hydroelectrolytic and metabolic alterations including fluid loss, electrolyte imbalances, and increased catabolism[2][3][4]

Closed

Closed wounds have fewer categories, but are just as dangerous as open wounds:

- Hematomas (or blood tumor) – caused by damage to a blood vessel that in turn causes blood to collect under the skin.

- Hematomas that originate from internal blood vessel pathology are petechiae, purpura, and ecchymosis. The different classifications are based on size.

- Hematomas that originate from an external source of trauma are contusions, also commonly called bruises.

- Crush injury – caused by a great or extreme amount of force applied over a long period of time.

An open wound (an avulsion)

An open wound (an avulsion) A laceration to the leg

A laceration to the leg An infected puncture wound to the bottom of the forefoot.

An infected puncture wound to the bottom of the forefoot. A puncture wound from playing darts.

A puncture wound from playing darts. An incision: a small cut in a finger.

An incision: a small cut in a finger. Fresh incisional wound on the fingertip of the left ring finger.

Fresh incisional wound on the fingertip of the left ring finger. Abrasion on knee

Abrasion on knee Bruise on arm

Bruise on arm

Presentation

Complications

Bacterial infection of wound can impede the healing process and lead to life-threatening complications. Scientists at Sheffield University have used light to rapidly detect the presence of bacteria, by developing a portable kit in which specially designed molecules emit a light signal when bound to bacteria. Current laboratory-based detection of bacteria can take hours or days.[5]

Workup

Wounds that are not healing should be investigated to find the causes; many microbiological agents may be responsible. The basic workup includes evaluating the wound, its extent and severity. Cultures are usually obtained both from the wound site and blood. X-rays are obtained and a tetanus shot may be administered if there is any doubt about prior vaccination.[6]

Chronic

Non-healing wounds of the diabetic foot are considered one of the most significant complications of diabetes, representing a major worldwide medical, social, and economic burden that greatly affects patient quality of life. Almost 24 million Americans—one in every twelve—are diabetic and the disease is causing widespread disability and death at an epidemic pace, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Of those with diabetes, 6.5 million are estimated to have chronic or non-healing wounds. Associated with inadequate circulation, poorly functioning veins, and immobility, non-healing wounds occur most frequently in the elderly and in people with diabetes—populations that are sharply rising as the nation ages and chronic diseases increase.

Although diabetes can ravage the body in many ways, non-healing ulcers on the feet and lower legs are common outward manifestations of the disease. Also, diabetics often experience nerve damage in their feet and legs, allowing small wounds or irritations to develop without awareness. Given the abnormalities of the microvasculature and other side effects of diabetes, these wounds take a long time to heal and require a specialized treatment approach for proper healing.

As many as 75% of diabetic patients will eventually develop foot ulcers, and recurrence within five years is 70%. If not aggressively treated, these wounds can lead to amputations. It is estimated that every 30 seconds a lower limb is amputated somewhere in the world because of a diabetic wound. Amputation often triggers a downward spiral of declining quality of life, frequently leading to disability and death. In fact, only about one third of diabetic amputees will live more than five years, a survival rate equivalent to that of many cancers.

Many of these lower extremity amputations can be prevented through an interdisciplinary approach to treatment involving a variety of advanced therapies and techniques, such as debridement, hyperbaric oxygen treatment therapy, dressing selection, special shoes, and patient education. When wounds persist, a specialized approach is required for healing.[7]

Management

The overall treatment depends on the type, cause, and depth of the wound, and whether other structures beyond the skin (dermis) are involved. Treatment of recent lacerations involves examining, cleaning, and closing the wound. Minor wounds, like bruises, will heal on their own, with skin discoloration usually disappearing in 1–2 weeks. Abrasions, which are wounds with intact skin (non-penetration through dermis to subcutaneous fat), usually require no active treatment except keeping the area clean, initially with soap and water. Puncture wounds may be prone to infection depending on the depth of penetration. The entry of puncture wound is left open to allow for bacteria or debris to be removed from inside.

Cleaning

Evidence to support the cleaning of wounds before closure is scant.[8] For simple lacerations, cleaning can be accomplished using a number of different solutions, including tap water and sterile saline solution.[8] Infection rates may be lower with the use of tap water in regions where water quality is high.[8] Cleaning of a wound is also known as 'wound toilet'.[9] It is not clear if delaying a shower following a surgery helps reduce complications related to wound healing.[10]

Wound cleansing solutions

Evidence is insufficient to conclude whether cleaning wounds is beneficial or whether wound cleaning solutions (polyhexamethylene biguanide, aqueous oxygen peroxide, etc.) are better than sterile water or saline solutions to help venous leg ulcers heal.[11] It is also uncertain whether the choice of cleaning solution or method of application makes any difference to venous leg ulcer healing.[11]

Closure

If a person presents to a healthcare center within 6 hours of a laceration they are typically closed immediately after evaluating and cleaning the wound. After this point in time, however, there is a theoretical concern of increased risks of infection if closed immediately.[12] Thus some healthcare providers may delay closure while others may be willing to immediately close up to 24 hours after the injury.[12] Using clean non-sterile gloves is equivalent to using sterile gloves during wound closure.[13]

If closure of a wound is decided upon a number of techniques can be used. These include bandages, a cyanoacrylate glue, staples, and sutures. Absorbable sutures have the benefit over non absorbable sutures of not requiring removal. They are often preferred in children.[14] Buffering the pH of lidocaine makes the injection less painful.[15] Adhesive glue and sutures have comparable cosmetic outcomes for minor lacerations <5 cm in adults and children.[16] The use of adhesive glue involves considerably less time for the doctor and less pain for the person. The wound opens at a slightly higher rate but there is less redness.[17] The risk for infections (1.1%) is the same for both. Adhesive glue should not be used in areas of high tension or repetitive movements, such as joints or the posterior trunk.[16] Split-thickness skin grafting (STSG) is also a surgical technique that features rapid wound closure, multiple possible donor sites with minimal morbidity.[18]

Dressings

In the case of clean surgical wounds, there is no evidence that the use of topical antibiotics reduces infection rates in comparison with non-antibiotic ointment or no ointment at all.[19] Antibiotic ointments can irritate the skin, slow healing, and greatly increase the risk of developing contact dermatitis and antibiotic resistance.[19] Because of this, they should only be used when a person shows signs of infection and not as a preventative.[19]

The effectiveness of dressings and creams containing silver to prevent infection or improve healing is not currently supported by evidence.[20]

Diagnosis

A wound may be recorded for follow-up and observing progress of healing with different techniques which include:[21]

- Photographs, with subsequent area quantification using computer processing

- Wound tracings on acetate sheets

- Kundin wound gauge

Alternative medicine

There is moderate evidence that honey is more effective than antiseptic followed by gauze for healing wounds infected after surgical operations. There is a lack of quality evidence relating to the use of honey on other types of wounds, such as minor acute wounds, mixed acute and chronic wounds, pressure ulcers, Fournier's gangrene, venous leg ulcers, diabetic foot ulcers and Leishmaniasis.[22]

There is no good evidence that therapeutic touch is useful in healing.[23] More than 400 species of plants are identified as potentially useful for wound healing.[24] Only three randomized controlled trials, however, have been done for the treatment of burns.[25]

History

From the Classical Period to the Medieval Period, the body and the soul were believed to be intimately connected, based on several theories put forth by the philosopher Plato. Wounds on the body were believed to correlate with wounds to the soul and vice versa; wounds were seen as an outward sign of an inward illness. Thus, a man who was wounded physically in a serious way was said to be hindered not only physically but spiritually as well. If the soul was wounded, that wound may also eventually become physically manifest, revealing the true state of the soul.[26] Wounds were also seen as writing on the "tablet" of the body. Wounds acquired in war, for example, told the story of a soldier in a form which all could see and understand, and the wounds of a martyr told the story of their faith.[26]

Research

In humans and mice it has been shown that estrogen might positively affect the speed and quality of wound healing.[27]

See also

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics (2011). First Aid for Families. Jones & Bartlett. p. 39. ISBN 978-0763755522.

- Rae L, Fidler P, Gibran N. The physiologic basis of burn shock and the need for aggressive fluidresuscitation. Crit Care Clin 2016;32(4):491-505.

- Mecott GA, Gonzalez-Cantu I, Dorsey-Trevino EG, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Pirfenidone in Patients with Second-Degree Burns: A Proof-of-Concept Randomized Controlled Trial. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2020;33(4):1-7. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000655484.95155.f7, 10.1097/01.ASW.0000655484.95155.f7

- Nielson CB, Duethman NC, Howard JM, et al. Burns: pathophysiology of systemic complications andcurrent management. J Burn Care Res 2017;38(1):e469-81.

- "Light to detect wound infection" (web). UK scientists have identified a way of using light to rapidly detect the presence of bacteria. BBC News. 11 March 2007. Archived from the original on 22 August 2007. Retrieved 17 March 2008.

- Work Up Archived 31 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine eMedicine General Surgery. Retrieved 27 January 2010

- "The Clinical Case for Use of Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy in the Treatment of Diabetic Wounds," Diversified Clinical Services, copyright 2009

- Fernandez R, Griffiths R (February 2012). "Water for wound cleansing". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2 (2): CD003861. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003861.pub3. PMID 22336796.

- Simple wound management Archived 27 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine, patient.info (website), accessed 8 January 2012

- Toon CD, Sinha S, Davidson BR, Gurusamy KS (July 2015). "Early versus delayed post-operative bathing or showering to prevent wound complications". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (7): CD010075. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010075.pub3. PMC 7092546. PMID 26204454.

- McLain NE, Moore ZE, Avsar P, et al. (Cochrane Wounds Group) (March 2021). "Wound cleansing for treating venous leg ulcers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021 (3): CD011675. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011675.pub2. PMC 8092712. PMID 33734426.

- Eliya-Masamba MC, Banda GW (October 2013). "Primary closure versus delayed closure for non bite traumatic wounds within 24 hours post injury". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (10): CD008574. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008574.pub3. PMID 24146332.

- Brewer JD, Gonzalez AB, Baum CL, Arpey CJ, Roenigk RK, Otley CC, Erwin PJ (September 2016). "Comparison of Sterile vs Nonsterile Gloves in Cutaneous Surgery and Common Outpatient Dental Procedures: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". JAMA Dermatology. 152 (9): 1008–14. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.1965. PMID 27487033.

- "BestBets: Absorbable sutures in pediatric lacerations". Archived from the original on 26 December 2008.

- Cepeda MS, Tzortzopoulou A, Thackrey M, Hudcova J, Arora Gandhi P, Schumann R (December 2010). Tzortzopoulou A (ed.). "Adjusting the pH of lidocaine for reducing pain on injection". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD006581. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006581.pub2. PMID 21154371. (Retracted, see doi:10.1002/14651858.cd006581.pub3)

- Cals JW, de Bont EG (October 2012). "Minor incised traumatic laceration". BMJ. 345: e6824. doi:10.1136/bmj.e6824. PMID 23092899. S2CID 32499629. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013.

- Farion K, Osmond MH, Hartling L, Russell K, Klassen T, Crumley E, Wiebe N (2002). Farion KJ (ed.). "Tissue adhesives for traumatic lacerations in children and adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010 (3): CD003326. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003326. PMC 9006881. PMID 12137689.

- Retrouvey H, Adibfar A, Shahrokhi S (January 2020). "Extremity Mobilization After Split-Thickness Skin Graft Application: A Survey of Current Burn Surgeon Practices". Annals of Plastic Surgery. 84 (1): 30–34. doi:10.1097/SAP.0000000000001993. PMID 31633538. S2CID 204815208.

- American Academy of Dermatology (February 2013), "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Academy of Dermatology, archived from the original on 1 December 2013, retrieved 5 December 2013, which cites

- Sheth VM, Weitzul S (2008). "Postoperative topical antimicrobial use". Dermatitis. 19 (4): 181–9. doi:10.2310/6620.2008.07094. PMID 18674453.

- D'Amico G, Pagliaro L, Pietrosi G, Tarantino I (March 2010). "Emergency sclerotherapy versus vasoactive drugs for bleeding oesophageal varices in cirrhotic patients". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD002233. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002233.pub2. PMC 7100539. PMID 20238318.

- Thomas AC, Wysocki AB (February 1990). "The healing wound: a comparison of three clinically useful methods of measurement". Decubitus. 3 (1): 18–20, 24–25. PMID 2322408.

- Jull AB, Cullum N, Dumville JC, Westby MJ, Deshpande S, Walker N (6 March 2015). "Honey as a topical treatment for wounds". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3 (3): CD005083. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005083.pub4. PMID 25742878.

- O'Mathúna DP (August 2016). O'Mathúna DP (ed.). "Therapeutic touch for healing acute wounds". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (8): CD002766. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002766.pub5. PMID 27552401. (Retracted, see doi:10.1002/14651858.cd002766.pub6)

- Ghosh PK, Gaba A (2013). "Phyto-extracts in wound healing". Journal of Pharmacy & Pharmaceutical Sciences. 16 (5): 760–820. doi:10.18433/j3831v. PMID 24393557.

- Bahramsoltani R, Farzaei MH, Rahimi R (September 2014). "Medicinal plants and their natural components as future drugs for the treatment of burn wounds: an integrative review". Archives of Dermatological Research. 306 (7): 601–17. doi:10.1007/s00403-014-1474-6. PMID 24895176. S2CID 23859340.

- Reichardt, Paul F. (1984). "Gawain and the image of the wound". PMLA. 99 (2): 154–61. doi:10.2307/462158. JSTOR 462158.

- Desiree May Oh, MD, Tania J. Phillips, MD (2006). "Sex Hormones and Wound Healing". Wounds. Archived from the original on 7 January 2013.

External links

- US based wound healing society

- Association for the Advancement of Wound Care AAWC

- European Wound Management Association – EWMA works to promote the advancement of education and research.