Subareolar abscess

Also called Zuska's disease (only nonpuerperal case), subareolar abscess is a subcutaneous abscess of the breast tissue beneath the areola of the nipple. It is a frequently aseptic inflammation and has been associated with squamous metaplasia of lactiferous ducts.

The term is usually understood to include breast abscesses located in the retroareolar region or the periareolar region[1][2] but not those located in the periphery of the breast.

Subareolar abscess can develop both during lactation or extrapuerperal, the abscess is often flaring up and down with repeated fistulation.

Pathophysiology

90% of cases are smokers, however only a very small fraction of smokers appear to develop this lesion. It has been speculated that either the direct toxic effect or hormonal changes related to smoking could cause squamous metaplasia of lactiferous ducts. It is not well established whether the lesion regresses after smoking cessation.

Extrapuerperal cases are often associated with hyperprolactinemia or with thyroid problems. Also diabetes mellitus may be a contributing factor in nonpuerperal breast abscess.[3][4]

Treatment

Treatment is problematic unless an underlying endocrine disorder can be successfully diagnosed and treated.

A study by Goepel and Panhke provided indications that the inflammation should be controlled by bromocriptine even in absence of hyperprolactinemia.[5]

Antibiotic treatment is given in case of acute inflammation. However, this alone is rarely effective, and the treatment of a subareaolar abscess is primarily surgical. In case of an acute abscess, incision and drainage are performed, followed by antibiotics treatment. However, in contrast to peripheral breast abscess which often resolves after antibiotics and incision and drainage, subareaolar breast abscess has a tendency to recur, often accompanied by the formation of fistulas leading from inflammation area to the skin surface. In many cases, in particular in patients with recurrent subareolar abscess, the excision of the affected lactiferous ducts is indicated, together with the excision of any chronic abscess or fistula. This can be performed using radial or circumareolar incision.[6]

There is no universal agreement on what should be the standard way of treating the condition. In a recent review article, antibiotics treatment, ultrasound evaluation and, if fluid is present, ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration of the abscess with an 18 gauge needle, under saline lavage until clear, has been suggested as initial line of treatment for breast abscess in puerperal and non-puerperal cases including central (subareolar) abscess[7] (see breast abscess for details). Elsewhere, it has been stated that treatment of subareolar abscess is unlikely to work if it does not address the ducts as such.[6]

Duct resection has been traditionally used to treat the condition; the original Hadfield procedure has been improved many times but long-term success rate remains poor even for radical surgery. Petersen even suggests that damage caused by previous surgery is a frequent cause of subareolar abscesses.[9] Goepel and Pahnke and other authors recommend performing surgeries only with concomitant bromocriptine treatment.[5]

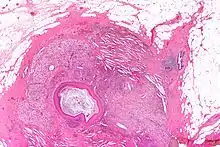

Squamous metaplasia of lactiferous ducts

Squamous metaplasia of lactiferous ducts - abbreviated SMOLD is a change where the normal double layer cuboid epithelium of the lactiferous ducts is replaced by squamous keratinizing cell layers. The resulting epithelium is very similar to normal skin, hence some authors speak of epidermalization. SMOLD is rare in premenopausal women (possibly 0.1-3%) but more frequent (possibly up to 25%) in postmenopausal women where it does not cause any problems at all.

SMOLD appears to be a completely benign lesion and may exist without causing any symptoms. In principle it ought to be completely reversible as the classification as metaplasia would suggest. Because of difficulties in observing the actual changes and rare incidence of the lesion this does not appear to be documented.

The last section of the lactiferous ducts is always lined with squamous keratinizing epithelium which appears to have important physiological functions. For example, the keratin forms plugs sealing the duct entry and has bacteriostatic properties. In SMOLD the keratinizing lining which is supposed to form only the ends of the lactiferous ducts extends deep into the ducts.

SMOLD is distinct from squamous metaplasia that may occur in papilomatous hyperplasia. It is believed to be unrelated to squamous cell carcinoma of the breast which probably arises from different cell types.

The keratin plugs (debris) produced by SMOLD have been proposed as the cause for recurrent subareolar abscesses by causing secretory stasis. The epidermalized lining has also different permeability than the normal lining, hindering resorption of glandular secretions. The resorption is necessary to dispose of stalled secretions inside the duct - and at least equally important it affects osmotic balance which in turn is an important mechanism in the control of lactogenesis (this is relevant both in puerperal and nonpuerperal mastitis).

While in lactating women this would appear to be a very plausible pathogenesis, there is some uncertainty about the pathogenesis in non-lactating women where breast secretions should be apriori minimal. It appears pathologic stimulation of lactogenesis must be present as well to cause subareolar abscess and treatment success with bromocriptin appears to confirm this[5] as compared to poor success rate of the usual antibiotic and surgical treatments documented by Hanavadi et al.

Further uncertainty in the relation of SMOLD and the subareolar abscess is that squamous metaplasia is very often caused by inflammatory processes. SMOLD could be the cause of the inflammation – or the result of a previous or longstanding inflammation.

SMOLD usually affects multiple ducts and frequently (relative to extremely low absolute prevalence) both breasts hence it is very likely that systemic changes such as hormonal interactions are involved.

At least the following factors have been considered in the aetiology of SMOLD: reactive change to chronic inflammation, systemic hormonal changes, smoking, dysregulation in beta-catenin expression, changes in retinoic acid and vitamin D metabolism or expression.

Vitamin A deficiency may cause epidermilization of the ducts and squamous metaplasia and likely also contributes to infection.[10] Vitamin A deficiency has been observed to cause squamous metaplasia in many types of epithelia. However supplementation with Vitamin A would be beneficial only in exceptional cases because normally the local catabolism of vitamin A will be the regulating factor.

Squamous metaplasia of breast epithelia is known to be more prevalent in postmenopausal women (where it does not cause any problems at all). Staurosporine, a nonspecific protein kinase C inhibitor can induce squamous metaplasia in breast tissue while other known PKC inhibitors did not show this effect. cAMP stimulation can also induce squamous metaplasia.[11]

Research

Multiple imaging modalities may be necessary to evaluate abnormalities of the nipple-areolar complex.[12][13]

In two studies performed in Japan, high-resolution MRI with a microscopy coil yielding 0.137-mm in-plane resolution has been used to confirm the presence of abscesses, isolated fistulas and inflammation and to reveal their position in order to guide surgery.[14][15]

References

- Michael S. Sabel (2009). Essentials of Breast Surgery. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-323-03758-7.

- Versluijs, F. N. L.; Roumen, R. M. H.; Goris, R. J. A. (2000). "Chronic recurrent subareolar breast abscess: incidence and treatment". British Journal of Surgery. 87 (7): 931–964. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01544-49.x. ISSN 0007-1323. S2CID 59165166.

- Rizzo M, Gabram S, Staley C, Peng L, Frisch A, Jurado M, Umpierrez G (March 2010). "Management of breast abscesses in nonlactating women". The American Surgeon. 76 (3): 292–5. doi:10.1177/000313481007600310. PMID 20349659. S2CID 25120670.

- Verghese BG, Ravikanth R (May 2012). "Breast abscess, an early indicator for diabetes mellitus in non-lactating women: a retrospective study from rural India". World Journal of Surgery. 36 (5): 1195–8. doi:10.1007/s00268-012-1502-7. PMID 22395343. S2CID 23073438.

- Goepel E, Pahnke VG (1991). "[Successful therapy of nonpuerperal mastitis – already routine or still a rarity?]". Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd (in German). 51 (2): 109–16. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1023685. PMID 2040409.

- Michael S. Sabel (2009). Essentials of Breast Surgery. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 85–88. ISBN 978-0-323-03758-7.

- Trop I, Dugas A, David J, El Khoury M, Boileau JF, Larouche N, Lalonde L (October 2011). "Breast abscesses: evidence-based algorithms for diagnosis, management, and follow-up". Radiographics (review). 31 (6): 1683–99. doi:10.1148/rg.316115521. PMID 21997989.

- Petersen EE (2003). Infektionen in Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe. Thieme Georg Verlag. ISBN 3-13-722904-9.

- Michael S. Sabel (2009). Essentials of Breast Surgery. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-323-03758-7.

- Heffelfinger SC, Miller MA, Gear R, Devoe G (1998). "Staurosporine-induced versus spontaneous squamous metaplasia in pre- and postmenopausal breast tissue". J. Cell. Physiol. 176 (2): 245–54. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199808)176:2<245::AID-JCP3>3.0.CO;2-O. PMID 9648912. S2CID 31853957.

- An HY, Kim KS, Yu IK, Kim KW, Kim HH (June 2010). "Image presentation. The nipple-areolar complex: a pictorial review of common and uncommon conditions". Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine (review). 29 (6): 949–62. doi:10.7863/jum.2010.29.6.949. PMID 20498469. S2CID 221893834.

- Sarica O, Zeybek E, Ozturk E (July 2010). "Evaluation of nipple-areola complex with ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging". Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography (review). 34 (4): 575–86. doi:10.1097/RCT.0b013e3181d74a88. PMID 20657228.

- Fu P, Kurihara Y, Kanemaki Y, Okamoto K, Nakajima Y, Fukuda M, Maeda I (June 2007). "High-resolution MRI in detecting subareolar breast abscess". AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology. 188 (6): 1568–72. doi:10.2214/AJR.06.0099. PMID 17515378.

- Enomoto S, Matsuzaki K (2012). "Treatment of inverted nipple with subareolar abscess: usefulness of high-resolution MRI for preoperative evaluation". Plastic Surgery International. 2012: 573079. doi:10.1155/2012/573079. PMC 3401517. PMID 22848806.

Further reading

- Kasales CJ, Han B, Smith JS, Chetlen AL, Kaneda HJ, Shereef S (February 2014). "Nonpuerperal mastitis and subareolar abscess of the breast". AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology (review). 202 (2): W133–9. doi:10.2214/AJR.13.10551. PMID 24450694. S2CID 27952386.