Superhydrophobic coating

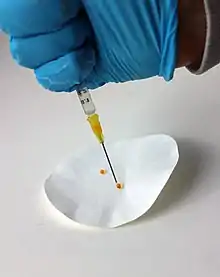

A superhydrophobic coating is a thin surface layer that repels water. It is made from superhydrophobic (ultrahydrophobicity) materials. Droplets hitting this kind of coating can fully rebound.[1][2] Generally speaking, superhydrophobic coatings are made from composite materials where one component provides the roughness and the other provides low surface energy.[3]

Material used

Superhydrophobic coatings can be made from many different materials. The following are known possible bases for the coating:

- Manganese oxide polystyrene (MnO2/PS) nano-composite

- Zinc oxide polystyrene (ZnO/PS) nano-composite[4]

- Precipitated calcium carbonate[5]

- Carbon nano-tube structures

- Silica nano-coating[6][7][8]

- Fluorinated silanes[9] and Fluoropolymer coatings.[10]

The silica-based coatings are perhaps the most cost effective to use.[11] They are gel-based and can be easily applied either by dipping the object into the gel or via aerosol spray. In contrast, the oxide polystyrene composites are more durable than the gel-based coatings, however the process of applying the coating is much more involved and costly. Carbon nano-tubes are also expensive and difficult to produce with current technology. Thus, the silica-based gels remain the most economically viable option at present.

Types of superhydrophobic coatings

Industrial uses

In industry, super-hydrophobic coatings are used in ultra-dry surface applications. The coating causes an almost imperceptibly thin layer of air to form on top of a surface. Super-hydrophobic coatings are also found in nature; they appear on plant leaves, such as the Lotus leaf, and some insect wings.[14] The coating can be sprayed onto objects to make them waterproof. The spray is anti-corrosive and anti-icing; has cleaning capabilities; and can be used to protect circuits and grids.

Superhydrophobic coatings have important applications in maritime industry. They can yield skin friction drag reduction for ships' hulls, thus increasing fuel efficiency. Such a coating would allow ships to increase their speed or range while reducing fuel costs. They can also reduce corrosion and prevent marine organisms from growing on a ship's hull.

In addition to these industrial applications, superhydrophobic coatings have potential uses in vehicle windshields to prevent rain droplets from clinging to the glass. The coatings also make removal of salt deposits possible without using fresh water. Furthermore, superhydrophobic coatings have the ability to aid harvesting minerals from seawater brine.[15] Despite the coating's many applications, safety for the environment and for workers is an issue. The International Maritime Organization has many regulations and policies about keeping water safe from potentially dangerous additives.

Superhydrophobic coatings rely on a delicate micro or nano structure for their repellence—this structure is easily damaged by abrasion or cleaning; therefore, the coatings are most used on things such as electronic components, which are not prone to wear. Objects subject to constant friction like boats hulls would require constant re-application of such a coating to maintain a high degree of performance.

Applications:- Due to the extreme repellence and in some cases bacterial resistance of hydrophobic coatings, there is much enthusiasm for their wide potential uses with surgical tools, medical equipment, textiles, and all sorts of surfaces and substrates. However, the current state of the art for this technology is hindered in terms of the weak durability of the coating making it unsuitable for most applications. Newer engineered surface textures on stainless steel are extremely durable and permanently hydrophobic. Optically these surfaces appear as a uniform matte surface but microscopically they consist of rounded depressions one to two microns deep over 25% to 50% of the surface. These surfaces are produced for buildings which will never need cleaning.[16]

There are many non-chemical companies on the Internet offering super hydrophobic coatings for various unsuitable applications. It is important to understand the science of these coatings before attempting to use this technology:

- Instead of using fluorine atoms for repellence like many successful hydrophobic penetrating sealers (not super hydrophobic), superhydrophobic products are a coating—they work by creating a micro- or nano-sized structure on a surface which has super-repellent properties.

- These very tiny structures are by their nature very delicate and very easily damaged by wear, cleaning or any sort of friction; if the structure is damaged even slightly it loses its superhydrophobic properties. This technology is based on the microstructure of the hairs of a lily pad which make water just roll off. Rub a lily leaf a little and it will no longer be superhydrophobic. Unlike a lily leaf, which can heal and grow new hairs, a coating will not do this.[17]

- As a result, unless advancements can resolve the identified weakness of this technology its applications are limited. It is used mainly in sealed environments which are not exposed to wear or cleaning, such as electronic components (like the inside of smart phones) and air conditioning heat transfer fins, to protect from moisture and prevent corrosion.[18]

Surfaces can be made hydrophobic without the use of coating through the altering of their surface microscopic contours, as well. The basis of hydrophobicity is the creation of recessed areas on a surface whose wetting expends more energy than bridging the recesses expends. This so-called Wenzel-effect surface or lotus effect surface has less contact area by an amount proportional to the recessed area, giving it a high contact angle. The recessed surface has a proportionately diminished attraction foreign liquids or solids and permanently stays cleaner. This has been effectively used for roofs and curtain walls of structures that benefit from low or no maintenance.[16]

See also

- Polytetrafluoroethylene

- Lotus effect

- Plant cuticle

- Biomimetics

- Hydrophobe

- Ultrahydrophobicity

- Non-stick surface

References

- Richard, Denis, Christophe Clanet, and David Quéré. "Surface phenomena: Contact time of a bouncing drop." Nature 417.6891 (2002): 811-811

- Yahua Liu, Lisa Moevius, Xinpeng Xu,Tiezheng Qian, Julia M Yeomans, Zuankai Wang. "Pancake bouncing on superhydrophobic surfaces." Nature Physics, 10, 515-519 (2014)

- Simpson, John T.; Hunter, Scott R.; Aytug, Tolga (2015). "Superhydrophobic materials and coatings: a review". Reports on Progress in Physics. 78 (8): 086501. Bibcode:2015RPPh...78h6501S. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/78/8/086501. PMID 26181655.

- Meng, Haifeng; Wang, Shutao; Xi, Jinming; Tang, Zhiyong; Jiang, Lei (2008). "Facile Means of Preparing Superamphiphobic Surfaces on Common Engineering Metals". The Journal of Physical Chemistry C. 112 (30): 11454–11458. doi:10.1021/jp803027w.

- Hu, Z.; Zen, X.; Gong, J.; Deng, Y. (2009). "Water resistance improvement of paper by superhydrophobic modification with microsized CaCO3 and fatty acid coating". Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects. 351 (1–3): 65–70. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2009.09.036.

- Lin, J.; Chen, H.; Fei, T.; Zhang, J. (2013). "Highly transparent superhydrophobic organic–inorganic nanocoating from the aggregation of silica nanoparticles". Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects. 421: 51–62. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2012.12.049.

- Das, I.; Mishra, M. K; Medda, S.K; De, G. (2014). "Durable superhydrophobic ZnO–SiO2 films: a new approach to enhance the abrasion resistant property of trimethylsilyl functionalized SiO2 nanoparticles on glass" (PDF). RSC Advances. 4 (98): 54989–54997. doi:10.1039/C4RA10171E.

- Torun, Ilker; Celik, Nusret; Hencer, Mehmet; Es, Firat; Emir, Cansu; Turan, Rasit; Onses, M.Serdar (2018). "Water Impact Resistant and Antireflective Superhydrophobic Surfaces Fabricated by Spray Coating of Nanoparticles: Interface Engineering via End-Grafted Polymers". Macromolecules. 51 (23): 10011–10020. Bibcode:2018MaMol..5110011T. doi:10.1021/acs.macromol.8b01808.

- Warsinger, David E.M.; Swaminathan, Jaichander; Maswadeh, Laith A.; Lienhard V, John H. (2015). "Superhydrophobic condenser surfaces for air gap membrane distillation". Journal of Membrane Science. Elsevier BV. 492: 578–587. doi:10.1016/j.memsci.2015.05.067. hdl:1721.1/102500.

- Servi, Amelia T.; Guillen-Burrieza, Elena; Warsinger, David E.M.; Livernois, William; Notarangelo, Katie; Kharraz, Jehad; Lienhard V, John H.; Arafat, Hassan A.; Gleason, Karen K. (2017). "The effects of iCVD film thickness and conformality on the permeability and wetting of MD membranes" (PDF). Journal of Membrane Science. Elsevier BV. 523: 470–479. doi:10.1016/j.memsci.2016.10.008. hdl:1721.1/108260.

- Shang HM, Wang Y, Limmer SJ, Chou TP, Takahashi K, Cao GZ (2005). "Optically transparent superhydrophobic silica-based films". Thin Solid Films. 472 (1–2): 37–43. Bibcode:2005TSF...472...37S. doi:10.1016/j.tsf.2004.06.087.

- "NeverWet Superhydrophobic Coatings – It Does Exactly What Its Name Implies" (PDF). Truworth Homes. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- "How to Apply NeverWet Rain Repellent". Rust-Oleum. 2 February 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2019 – via YouTube.

- Dai, S.; Ding, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Du, Z. (2011). "Fabrication of hydrophobic inorganic coatings on natural lotus leaves for nanoimprint stamps". Thin Solid Films. 519 (16): 5523. arXiv:1106.2228. Bibcode:2011TSF...519.5523D. doi:10.1016/j.tsf.2011.03.118. S2CID 98801618.

- Kahn, Mariam; Al-Ghouti, Mohammad A. (15 October 2021). "DPSIR framework and sustainable approaches of brine management from seawater desalination plants in Qatar". Journal of Cleaner Production. 319: 128485. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128485.

- McGuire, Michael F., "Stainless Steel for Design Engineers", ASM International, 2008.

- Ensikat, Hans J (10 March 2011). "Superhydrophobicity in perfection: the outstanding properties of the lotus leaf".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Milionis, Athanasios; Loth, Eric; Bayer, Ilker S. (2016). "Recent advances in the mechanical durability of superhydrophobic materials". Advances in Colloid and Interface Science. 229: 57–79. doi:10.1016/j.cis.2015.12.007. PMID 26792021.