Healthcare in Switzerland

The healthcare in Switzerland is universal[3] and is regulated by the Swiss Federal Law on Health Insurance. There are no free state-provided health services, but private health insurance is compulsory for all persons residing in Switzerland (within three months of taking up residence or being born in the country).[4][5][6]

Health insurance covers the costs of medical treatment and hospitalisation of the insured. However, the insured person pays part of the cost of treatment. This is done (a) by means of an annual deductible (called the franchise), which ranges from CHF 300 (PPP-adjusted US$ 184) to a maximum of CHF 2,500 (PPP-adjusted $1,534) for an adult as chosen by the insured person (premiums are adjusted accordingly) and (b) by a charge of 10% of the costs over and above the excess up to a stop-loss amount of CHF 700 (PPP-adjusted $429).

Compulsory coverage and costs

Swiss residents are required to purchase basic health insurance, which covers a range of treatments detailed in the Swiss Federal Law on Health Insurance (German: Krankenversicherungsgesetz (KVG); French: la loi fédérale sur l’assurance-maladie (LAMal); Italian: legge federale sull’assicurazione malattie (LAMal)). It is therefore the same throughout the country and avoids double standards in healthcare. Insurers are required to offer this basic insurance to everyone, regardless of age or medical condition. They are not allowed to make a profit off this basic insurance but can on supplemental plans.[3]

The insured person pays the insurance premium for the basic plan. If a premium is too high compared to the person's income, the government gives the insured person a cash subsidy to help pay for the premium.[7]

The universal compulsory coverage provides for treatment in case of illness or accident (unless another accident insurance provides the cover) and pregnancy.

Health insurance covers the costs of medical treatment and hospitalization of the insured. However, the insured person pays part of the cost of treatment. This is done by these ways:

- by means of an annual excess (or deductible, called the franchise), which ranges from CHF 300 (PPP-adjusted US$ 184) to a maximum of CHF 2,500 (PPP-adjusted $1,534) for an adult as chosen by the insured person (premiums are adjusted accordingly);

- by a charge of 10% of the costs over and above the excess. This is known as the retention and is up to a maximum of 700CHF (PPP-adjusted $429) per year.

In case of pregnancy, there is no charge. For hospitalisation, one pays a contribution to room and service costs.

Insurance premiums vary from insurance company to company (health insurance funds; German: Krankenkassen; French: caisses-maladie; Italian: casse malati), the excess level chosen (franchise), the place of residence of the insured person and the degree of supplementary benefit coverage chosen (complementary medicine, routine dental care, half-private or private ward hospitalisation, etc.).

In 2014, the average monthly compulsory basic health insurance premiums (with accident insurance) in Switzerland are the following:[8]

- CHF 396.12 (PPP-adjusted US$ 243) for an adult (age 26+)

- CHF 363.55 (PPP-adjusted $223) for a young adult (age 19–25)

- CHF 91.52 (PPP-adjusted $56.14) for a child (age 0–18)

International civil servants, members of embassies, and their family members are exempted from compulsory health insurance. Requests for exemptions are handled by the respective cantonal authority and have to be addressed to them directly.[9]

Private coverage

The compulsory insurance can be supplemented by private "complementary" insurance policies that allow for coverage of some of the treatment categories not covered by the basic insurance or to improve the standard of room and service in case of hospitalisation. This can include complementary medicine, routine dental treatments, half-private or private ward hospitalisation, and others, which are not covered by the compulsory insurance.

Premiums

As far as the compulsory health insurance is concerned, the insurance companies cannot set any conditions relating to age, sex or state of health for coverage. Although the level of premium can vary from one company to another, they must be identical within the same company for all insured persons of the same age group and region, regardless of sex or state of health. This does not apply to complementary insurance, where premiums are risk-based.

Organization

_(edit).jpg.webp)

The Swiss healthcare system is a combination of public, subsidised private and totally private systems:

- public: e. g. the University Hospital of Geneva (HUG) with 2,350 beds, 8,300 staff and 50,000 patients per year;

- subsidised private: the home care services to which one may have recourse in case of a difficult pregnancy, after childbirth, illness, accident, handicap or old age;

- totally private: doctors in private practice and in private clinics.

The insured person has full freedom of choice among the recognised healthcare providers competent to treat their condition (in their region) on the understanding that the costs are covered by the insurance up to the level of the official tariff. There is freedom of choice when selecting an insurance company (provided it is an officially registered caisse-maladie or a private insurance company authorised by the federal law) to which one pays a premium, usually on a monthly basis.

The list of officially approved insurance companies can be obtained from the cantonal authority.

Electronic health records

Before the discussions about a nationwide implementation, electronic health records were widely used in both private and public healthcare organizations.[10]

In 2207, the Swiss Federal Government approved a national strategy for adoption of e-health.[11] A central element of this strategy is a nationwide electronic health record. Following the federal tradition of Switzerland, it is planned that the infrastructure will be implemented in a decentralized way, i.e., using an access and control mechanism for federating existing records. In order to govern legal and financial aspects of the future nationwide EHR implementation, a bill was passed by the Swiss Federal Government in 2013 but left open questions regarding mandatory application.[12] The Federal Act on the Electronic Patient Record came into force on 15 April 2017, but the records were not universally available until 2020. It will be extended to birth centres and nursing homes in 2022. Both patients and clinicians can store and access health data in the records.[13]

Primary care

The ‘netCare’ scheme for minor ailments was introduced nationally in 2016. Pharmacists conduct a standardised triage and can prescribe medication. They can also have an unscheduled teleconsultation with a physician.[14]

Hospitals

Statistics

Healthcare costs in Switzerland are 11.4% of GDP (2010), comparable to Germany and France (11.6%) and other European countries, but significantly less than in the USA (17.6%). By 2015 the cost had risen to 11.7% of GDP -the second highest in Europe.[15] Benefits paid out as a percentage of premiums were 90.4% in 2011. Total gross benefits per person and per year in 2011 were CHF 3,171 (PPP-adjusted US$1,945), of which CHF 455 (PPP-adjusted $279) are cost sharing.[16]

According to the OECD Switzerland has the highest density of nurses among 27 measured countries, namely 17.4 nurses per thousand people in 2013.[17] The density of practising physicians is 4 per thousand population.[18]

In the 2018 Euro health consumer index survey Switzerland was placed first overtaking the Netherlands, and described as an excellent, although expensive, healthcare system.[19]

See also

- Health in Switzerland

- Healthcare in Europe

- Healthcare in Liechtenstein

- Medical schools

Notes and references

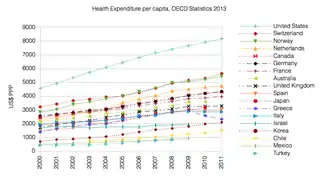

- "OECD.StatExtracts, Health, Health Expenditure and Financing, Main Indicators, Health Expenditure since 2000" (Online Statistics). OECD.Stats. OECD's iLibrary. 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

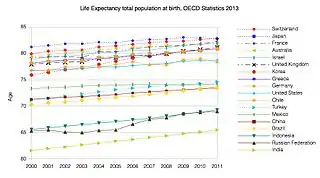

- "OECD.StatExtracts, Health, Health Status, Life expectancy, Total population at birth, 2011" (Online Statistics). OECD.Stats. OECD's iLibrary. 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- Schwartz, Nelson D. (1 October 2009). "Swiss health care thrives without public option". The New York Times. p. A1.

- "Requirement to take out insurance, "Frequently Asked Questions" (FAQ)". Swiss Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH), Federal Department of Home Affairs FDHA. 8 January 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- "Requirement to take out insurance: Persons residing in Switzerland". Swiss Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH), Federal Department of Home Affairs FDHA. 8 January 2012. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- "The compulsory health insurance in Switzerland: Your questions, our answers". Swiss Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH), Federal Department of Home Affairs FDHA. 21 December 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 December 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- FOPH, Federal Office of Public Health. "Health insurance: Key points in brief". www.bag.admin.ch.

- "Average compulsory basic health insurance premiums by canton for 2013/2014 (with accident insurance)" (PDF). Federal Office of Public Health. 17 September 2013.

- "Befreiung vom Versicherungsobligatorium: Liste der kantonalen Stellen für Gesuche um Befreiung von der obligatorischen Krankenversicherung" (PDF) (in German). Swiss Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH), Federal Department of Home Affairs FDHA. 27 August 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- Mettler T (2012). Post-Acceptance of Electronic Medical Records: Evidence from a Longitudinal Field Study. International Conference on Information Systems. Icis 2012 Proceedings.

- "eHealth - elektronische Gesundheitsdienste". Bundesamt für Gesundheit (BAG). Archived from the original on 22 January 2011.

- "Bundesgesetz über das elektronische Patientendossier". Die Bundesversammlung — Das Schweizer Parlament. 29 May 2013.

- "TCM therapists and their possibility to participate in the Electronic Patient Record". Lexology. 28 November 2018. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- "Pharmacists hold teleconsultations with doctors under nationwide Swiss scheme". Pharmaceutical Journal. 6 September 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- Ballas, Dimitris; Dorling, Danny; Hennig, Benjamin (2017). The Human Atlas of Europe. Bristol: Policy Press. p. 79. ISBN 9781447313540.

- "Statistical Data on Health and Accident Insurance, 2012 Edition (Flyer, A4, 2 pages)". Swiss Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH), Federal Department of Home Affairs FDHA. 19 December 2012. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- "Health Care Resources: Nurses Density 2013". OECD.Stats (online statistics). OECD's iLibrary. 2 November 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- "Health Care Resources: Physician Density 2013". OECD.Stats (online statistics). OECD's iLibrary. 2 November 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- "Outcomes in EHCI 2018" (PDF). Health Consumer Powerhouse. 25 February 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2020.