Tobacco smoke enema

The tobacco smoke enema, an insufflation of tobacco smoke into the rectum by enema, was a medical treatment employed by European physicians for a range of ailments.

Tobacco was recognised as a medicine soon after it was first imported from the New World, and tobacco smoke was used by western medical practitioners as a tool against cold and drowsiness, but applying it by enema was a technique appropriated from the North American Indians. The procedure was used to treat gut pain, and attempts were often made to resuscitate victims of near drowning. Liquid tobacco enemas were often given to ease the symptoms of a hernia.

During the early 19th century the practice fell into decline, when it was discovered that the principal active agent in tobacco smoke, nicotine, is poisonous.

Tobacco in medicine

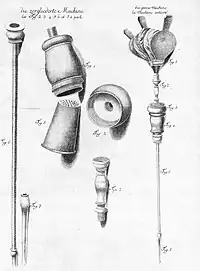

A: Pig's bladder.

FG: Smoking pipe.

D: Mouthpiece to which the pipe is attached.

E: Tap.

K: Cone for rectal insertion.

Before the Columbian Exchange, tobacco was unknown in the Old World. The Native Americans, from whom the first western explorers learnt about tobacco, used the leaf for a variety of purposes, including religious worship, but Europeans soon became aware that the Americans also used tobacco for medicinal purposes. The French diplomat Jean Nicot used a tobacco poultice as an analgesic, and Nicolás Monardes advocated tobacco as a treatment for a long list of diseases, such as cancer, headaches, respiratory problems, stomach cramps, gout, intestinal worms and female diseases.[1] Contemporaneous medical science placed much weight on humorism, and for a short period tobacco became a panacea. Its use was mentioned in pharmacopoeia as a tool against cold and somnolence brought on by particular medical afflictions,[2] its effectiveness being explained by its ability to soak up moisture, to warm parts of the body, and to therefore maintain the equilibrium so important to a healthy person.[3] In an attempt to discourage disease tobacco was also used to fumigate buildings.[4]

In addition to the Native Americans' use of tobacco smoke enemas for stimulating respiration, European physicians also employed them for a range of ailments, e.g., headaches, respiratory failure, colds, hernias, abdominal cramps, typhoid fever, and cholera outbreaks.[5]

An early example of European use of this procedure was described in 1686 by Thomas Sydenham, who to cure iliac passion prescribed first bleeding, followed by a tobacco smoke enema:

Here, therefore, I conceive it most proper to bleed first in the arm, and an hour or two afterwards to throw up a strong purging glyster; and I know of none so strong and effectual as the smoke of tobacco, forced up through a large bladder into the bowels by an inverted pipe, which may be repeated after a short interval, if the former, by giving a stool, does not open a passage downwards.

— Thomas Sydenham[6]

However, emulating the Catawba, 19th-century Danish farmers reportedly used these enemas for constipated horses.[7]

Medical opinion

To physicians of the time, the appropriate treatment for "apparent death" was warmth and stimulation. Anne Greene, a woman sentenced to death and hanged in 1650 for the supposed murder of her stillborn child, was found by anatomists to be still alive. They revived her by pouring hot cordial down her throat, rubbing her limbs and extremities, bleeding her, applying heating plasters and a "heating odoriferous Clyster to be cast up in her body, to give heat and warmth to her bowels." After placing her in a warm bed with another woman, to keep her warm, she recovered fully and was pardoned.[8]

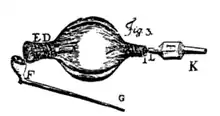

Artificial respiration and the blowing of smoke into the lungs or the rectum were thought to be interchangeably useful, but the smoke enema was considered the most potent method, due to its supposed warming and stimulating properties.[2] The Dutch experimented with methods of inflating the lungs, as a treatment for those who had fallen into their canals and apparently drowned. Patients were also given rectal infusions of tobacco smoke, as a respiratory stimulant.[9] Richard Mead was among the first Western scholars to recommend tobacco smoke enemas to resuscitate victims of drowning, when in 1745 he recommended tobacco glysters to treat iatrogenic drowning caused by immersion therapy. His name was cited in one of the earliest documented cases of resuscitation by rectally applied tobacco smoke, from 1746, when a seemingly drowned woman was treated. On the advice of a passing sailor, the woman's husband inserted the stem of the sailor's pipe into her rectum, covered the bowl with a piece of perforated paper, and "blew hard". The woman was apparently revived.[2]

In the 1780s the Royal Humane Society installed resuscitation kits, including smoke enemas, at various points along the River Thames,[2] and by the turn of the 19th century, tobacco smoke enemas had become an established practice in Western medicine, considered by Humane Societies to be as important as artificial respiration.[10]

"Tobacco glyster, breath and bleed.

Keep warm and rub till you succeed.

And spare no pains for what you do;

May one day be repaid to you."

By 1805, the use of rectally applied tobacco smoke was so established as a way to treat obstinate constrictions of the alimentary canal that doctors began experimenting with other delivery mechanisms.[12] In one experiment, a decoction of half a drachm of tobacco in four ounces of water was used as an enema in a patient suffering from general convulsion where there was no expected recovery.[12] The decoction worked as a powerful agent to penetrate and "roused the sensibility" of the patient to end the convulsions, although the decoction resulted in excited sickness, vomiting, and profuse perspiration.[12] Such enemas were often used to treat hernias. A middle-aged man was reported in 1843 to have died following an application, performed to treat a strangulated hernia,[13] and in a similar case in 1847 a woman was given a liquid tobacco enema, supplemented with a chicken broth enema, and pills of opium and calomel (taken orally). The woman later recovered.[14]

In 1811, a medical writer noted that "[t]he powers of the Tobacco Enema are so remarkable, that they have arrested the attention of practitioners in a remarkable manner. Of the effects and the method of exhibiting the smoke of Tobacco per anum, much has been written", providing a list of European publications on the subject.[15] Smoke enemas were also used to treat various other afflictions. An 1827 report in a medical journal tells of a woman treated for constipation with repeated smoke enemas, with little apparent success.[16] According to a report of 1835, tobacco enemas were used successfully to treat cholera "in the stage of collapse".[17]

I may observe, that before I was called to this case, stercoraceous vomiting had decidedly set in. My object in ordering the tobacco infusion and smoke enemata was to favour the reduction of any obscure hernia or muscular spasm of the bowel which might exist. I also directed that the attendants of the girl should, after she had taken the crude mercury, frequently raise her up in bed, (she was too feeble to raise herself,) to alter her position from one side to the other, from the back to the belly, and vice versa, with the view of favouring the gravitation of the mercury to the lower bowels.

— Robert Dick, M.D. (1847)[18]

Decline

Attacks on the theories surrounding the ability of tobacco to cure diseases had begun early in the 17th century. King James I was scathing of its effectiveness, writing "[it] will not deigne to cure heere any other than cleanly and gentlemanly diseases." Others claimed that smoking dried out the humours, that snuff made the brain sooty, and that old people should not smoke as they were naturally dried up anyway.[19]

While certain beliefs regarding the effectiveness of tobacco smoke to protect against disease persisted until well into the 20th century,[20] the use of smoke enemas in Western medicine declined after 1811, when through animal experimentation Benjamin Brodie demonstrated that nicotine—the principal active agent in tobacco smoke—is a cardiac poison that can stop the circulation of blood.[10]

See also

- Enema

- History of tobacco

The dictionary definition of blow smoke up someone's ass at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of blow smoke up someone's ass at Wiktionary

References

- Kell 1965, pp. 99–102

- Lawrence 2002, p. 1442

- Kell 1965, p. 103

- Meiklejohn 1959, p. 68

- Sterling Haynes, MD (December 2012). "Special feature: Tobacco smoke enemas". British Columbia Medical Journal. Doctors of BC. Retrieved 2019-03-29.

- Sydenham 1809, p. 383

- Kell 1965, p. 109

- Hughes 1982, p. 1783

- Price 1962, p. 67

- Hurt et al. 1996, p. 120

- Lowndes 1883, p. 1142

- Currie 1805, p. 164

- Japiot 1844, p. 324

- Long 1847, p. 320

- Anon2 1811, p. 226

- Jones 1827, p. 488

- Anon1 1835, p. 485

- Dick 1847, p. 276

- Kell 1965, p. 104

- Kell 1965, p. 106

Bibliography

- Anon1 (1835), "Accounts of several cases of Cholera, treated by Tobacco Enema, extracted from the Proceedings of the Society", Transactions of the Medical and Physical Society of Calcutta, 7

- Anon2 (1811), "Remarks on the History and Use of Tobacco", The Medical and Physical Journal, vol. 25

- Currie, James (1805), Medical Reports, on the Effects of Water, Cold and Warm: As a Remedy in Fever and Other Diseases, Whether Applied to the Surface of the Body, Or Used Internally, vol. 1, London: T. Cadell and W. Davies

- Dick, Robert (1847), Thomas Wakley, Surgeon (ed.), "The Treatment of Dyspepsia", The Lancet, 49 (1228): 275–276, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)86623-5

- Hurt, Raymond; Barry, J. E.; Adams, A. P.; Fleming, P. R. (1996), The History of Cardiothoracic Surgery from Early Times, Informa Health Care, ISBN 978-1850706816

- Hughes, Trevor J. (1982), "Miraculous Deliverance Of Anne Green: An Oxford Case Of Resuscitation In The Seventeenth Century", British Medical Journal, 285 (6357): 1792–1793, doi:10.1136/bmj.285.6357.1792, JSTOR 29509089, PMC 1500297, PMID 6816370

- Japiot, M. (1844), "Death Occasioned by the Administration of a Tobacco Enema", Provincial Medical Journal and Retrospect of the Medical Sciences, 7 (174): 324, JSTOR 25492616

- Jones, John (1827), "Constipation of the Bowels during twenty-one days, successfully treated.", The London Medical and Physical Journal, 58

- Kell, Katharine T. (1965), "Tobacco in Folk Cures in Western Society", The Journal of American Folklore, 78 (308): 99–114, doi:10.2307/538277, JSTOR 538277

- Lawrence, Ghislaine (20 April 2002), "Tools of the Trade, Tobacco smoke enemas", The Lancet, 359 (9315): 1442, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08339-3, S2CID 54371569, retrieved 2008-11-27

- Long, Dr Richard (1847), "Opium in Strangulated Hernia", Provincial Medical & Surgical Journal, BMJ, vol. 11, no. 12, p. 320, JSTOR 25499878

- Lowndes, Frederick Walter (1883), "Fifty-First Annual Meeting Of The British Medical Association", The British Medical Journal, 1 (1171): 1141–1152, doi:10.1136/bmj.1.1171.1141, JSTOR 25263327, S2CID 220003471

- Meiklejohn, A. (1959), "Outbreak of Fever in Cotton Mills at Radcliffe, 1784", British Journal of Industrial Medicine, 16 (1): 68–69, doi:10.1136/oem.16.1.68, PMC 1037863

- Nordenskiold, Erland (1929), "The American Indian as an Inventor", Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 59: 273–309, doi:10.2307/2843888, JSTOR 2843888

- Price, J. L. (1962), "The Evolution of Breathing Machines", Medical History, 6 (1): 67–72, doi:10.1017/s0025727300026867, PMC 1034674, PMID 14488739

- Sydenham, Thomas (1809), "Schedula Monitoria, or an Essay on the Rise of a New Fever", in Benjamin Rush (ed.), The works of Thomas Sydenham, M.D., on acute and chronic diseases: with their histories and modes of cure, Philadelphia: B. & T. Kite