Tracheal deviation

Tracheal deviation is a clinical sign that results from unequal intrathoracic pressure within the chest cavity. It is most commonly associated with traumatic pneumothorax, but can be caused by a number of both acute and chronic health issues, such as pneumonectomy, atelectasis, pleural effusion, fibrothorax (pleural fibrosis), or some cancers (tumors within the bronchi, lung, or pleural cavity) and certain lymphomas associated with the mediastinal lymph nodes.

In most adults and children, the trachea can be seen and felt directly in the middle of the anterior (front side) neck behind the jugular notch of the manubrium and superior to this point as it extends towards the larynx. However, when tracheal deviation is present, the trachea will be displaced in the direction of less pressure. Meaning, that if one side of the chest cavity has an increase in pressure (such as in the case of a pneumothorax) the trachea will shift towards the opposing side.[1]

The trachea is the tube that carries air from the throat to the lungs. It is also commonly referred to as the windpipe. The trachea is one of the most important parts of the respiratory system and damage to the trachea can indicate a life-threatening emergency. The normal position of the trachea is straight up and down, running along the center of the front side of the throat. Certain conditions can cause the trachea to shift to one side or the other. This is a medical emergency that requires immediate medical attention to discover the cause of the shift and begin an appropriate course of treatment. There are several causes for a tracheal deviation, and the condition often presents along with difficulty breathing, coughing and abnormal breath sounds. The most common cause of tracheal deviation is a pneumothorax, which is a collection of air inside the chest, between the chest cavity and the lung. A pneumothorax can be spontaneous, caused by existing lung disease, or by trauma. Treatment varies, depending on the severity of the pneumothorax. Smaller pockets of air tend to dissipate on their own, while larger areas can cause complications and are usually vented by a needle in the chest. As soon as the pneumothorax is treated, the tracheal deviation also will resolve itself.[2] A congenital lack of one lung, surgical removal of a lung or pleural fibrosis, which is an inflammation of the lung membranes caused by an infection. As a result of the wide range of causes of tracheal deviation, it is essential to seek medical attention so that an accurate diagnosis can be obtained.

| Towards side (ipsilateral) of Lung Lesion | Away from side (contralateral) of Lung Lesion | Other Causes (Mediastinal Masses) |

|---|---|---|

| Upper lobe or lung collapse | Tension pneumothorax | Retrosternal goitre |

| Upper lobe fibrosis | Massive pleural effusion | Lung cancer |

| Pneumonectomy | Lymphoma |

Normal variation

In children, where trachea is more flexible, it can be displaced by the aortic arch up to 90 degrees. The trachea can also be displaced to the left if the aortic arch lies to the right of the trachea.[4]

Treatment

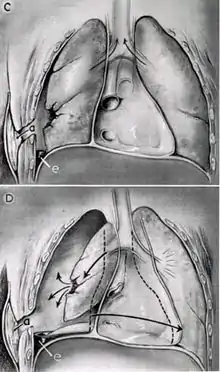

Since tracheal deviation is a sign as opposed to a condition, treatment is focused on correcting the cause of the finding. In the case of pneumothorax, thoracentesis or chest tube insertion is performed to relieve the pressure within the affected pleural cavity.

References

- Khajotia, R (2012-04-30). "Respiratory Clinics: MEDIASTINAL SHIFT: A SIGN OF SIGNIFICANT CLINICAL AND RADIOLOGICAL IMPORTANCE IN DIAGNOSIS OF MALIGNANT PLEURAL EFFUSION". Malaysian Family Physician. 7 (1): 34–36. ISSN 1985-207X. PMC 4170449. PMID 25606244.

- "Pneumothorax Clinical Presentation: History, Physical Examination". emedicine.medscape.com. Retrieved 2016-11-28.

- Macleod's clinical examination. Douglas, Graham (Consultant physician),, Nicol, E. Fiona,, Robertson, Colin (Colin Ernest) (Thirteenth ed.). Edinburgh. 2013. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-7020-4728-2. OCLC 821067736.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Ryan, Stephanie (2011). "Chapter 3". Anatomy for diagnostic imaging (Third ed.). Elsevier Ltd. p. 122. ISBN 9780702029714.

- Hillegass, E. (2011). Essentials of Cardiopulmonary Physical Therapy. 3rd Edition. pg. 554