Coronary artery bypass surgery

Coronary artery bypass surgery, also known as coronary artery bypass graft (CABG, pronounced "cabbage") is a surgical procedure for coronary artery disease (CAD) aiming to relieve angina, stall progression of ischemic heart disease and increase life expectancy. The goal is to bypass the stenotic lesions in native heart arteries using arterial or venous conduits, thus restoring adequate blood supply to the previously ischemic heart.

| Coronary artery bypass surgery | |

|---|---|

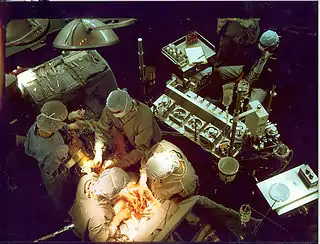

Early in a coronary artery bypass operation, during vein harvesting from the legs (left of image) and the establishment of cardiopulmonary bypass by placement of an aortic cannula (bottom of image). The perfusionist and heart-lung machine are on the upper right. The patient's head (not seen) is at the bottom. | |

| Other names | Coronary artery bypass graft |

| ICD-10-PCS | 021209W |

| ICD-9-CM | 36.1 |

| MeSH | D001026 |

| MedlinePlus | 002946 |

There are two main approaches. The first utilizes a cardiopulmonary bypass machine and with the heart in arrest (while protected), anastomosis of arterial or venous conduits are constructed. In the other approach, named Off-pump coronary artery bypass graft (OPCABG), anastomoses are constructed while the heart is still beating. The anastomosis supplying the left anterior descending branch (LAD) is the most significant one and usually, the left internal mammary artery (LIMA) is used as the graft. Other commonly employed conduits are the right internal mammary artery (RITA), the radial artery or great saphenous vein (SVG).

Since the beginning of the 20th century, the medical community was searching for an effective way to treat angina. In the 1960's CABG was introduced in the form we know today and has since become the main treatment option for significant CAD. Significant complications of the operation include bleeding, heart problems (Myocardial infarction, Arrhythmias), stroke, infections (often pneumonia) and kidney injury.

Uses

The scope of the operation is to prevent death from coronary artery disease (CAD) and improve quality of life by relieving chest pain.[1] Indications for surgery are based on studies examining the pros and cons of CABG in various subgroups of patients (depending on the anatomy of the lesions or how well heart is functioning) with CAD and comparing it with other therapeutic strategies, most importantly PCI. [2][3]

Coronary artery disease

Coronary artery disease is caused when coronary arteries of the heart accumulate atheromatic plaques, causing stenosis in one or more arteries and place myocardium at risk of myocardial infarction. CAD can occurs in any of the major vessels of coronary circulation, which are Left Main Stem, Left Ascending Artery, Circumflex artery, and Right Coronary Artery and their branches. CAD can be asymptomatic for some time- causing no trouble, can produce chest pain when patient is exercising, or can produce angina even at rest. The former is called stable angina, while the latter unstable angina. Worse, it can manifest as a myocardial infarction, in (which the blood flow to a part of myocardium is blocked. If the blood flow is not restored within a few hours, either spontaneously or by medical intervention, the specific part of the myocardium becomes necrotic (dies) and is replaced by a scar. It might even lead to other complications such as arrhythmias, rapture of the papillary muscles of the heart, or sudden death.[4]

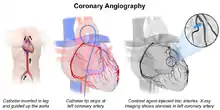

Medical community has various modalities to detect CAD and examine its extent. Apart from history and clinical examination, noninvasive methods include Electrocardiography (ECG) (at rest or during exercise) and chest X-ray. Echocardiography can provide useful information on the functioning of myocardium, as the enlargement of Left Ventricle , the Ejection Fraction and the situation of heart valves. The best modalities to accurately detect CAD though are the coronary angiogram and the Coronary CT angiography.[4] Angiogram can provide detailed anatomy of coronary circulation and lesions albeit not perfect. Significance of each lesions is determined by the diameter loss. Diameter loss of 50% translates to a 75% cross-sectional area loss which is considered moderate, by most groups. Severe stenosis is considered when the diameter loss is 2/3 of original diameter or more, that is 90% loss of cross-sectional area loss or more.[5] To determine the severity of stenosis more accurately, interventional cardiologists might also employ Intravascular ultrasound. Intravascular ultrasound utilizes ultrasound technology to determine the severity of stenosis and provide information on the composition of the atheromatic plaque. Fractional flow reserve also can be of use. With FFR, the post-stenotic pressure is compared to mean aortic pressure. If the value is <0,80, then the stenosis is deemed significant.[5]

Stable patients

People suffering from angina during exercise are usually first treated with medical therapy. Noninvasive tests (as stress test, nuclear imaging, dobutamine stress echocardiography) help estimate which patients might benefit from undergoing coronary angiography. Many factors are taken into account but generally, people whose tests reviled that portions of cardiac wall receive less blood that normally should proceed with coronary angiography. There, lesions are identified and a decision is taken whether patient should undergo PCI or GABG.[6]

Generally, CABG is preferred over PCI when there is significant atheromatic burden on the coronaries, that is extensive and complex. According to current literature, decreased LV function, LM disease, complex triple system disease (including LAD, Cx and RCA) especially when the lesion at LAD is at its proximal part and diabetes, are factors that point patients will benefit more from CABG rather than PCI.[2][3]

Acute coronary syndrome

During an acute heart event, named acute coronary syndrome, it is of vital importance to restore blood flow to the myocardium as fast as possible. Typically, patients arrive at hospital with chest pain. Initially they are treated with medical drugs, particularly the strongest drugs that prevent clots within vessels (dual antiplatelet therapy: aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor-like clopidogrel). Patients at risk of ongoing ischemia, undergo PCI and restore blood flow and thus oxygen delivery to the struggling myocardium.[7] In cases where PCI failed to restore blood flow because of anatomic considerations or other technical problems, urgent CABG is indicated to save myocardium. It has also been noted that the timing of the operation, plays a role in survival, it is preferable to delay the surgery if possible (6 hours in cases of nontransmural MI, 3 days in cases of transmural MI)[2]

CABG of coronary lesions is also indicated in mechanical complications of an infarction (ventricular septal defect, papillary muscle rupture or myocardial rupture) should be addressed[8] There are no absolute contraindications of CABG but severe disease of other organs such as liver or brain, limited life expectancy, fragility should be taken into consideration when planning the treatment path of a patient.[8]

Other cardiac surgery

CABG is also performed when a patient is to undergo another cardiac surgical procedure, most commonly for valve disease, and at angiography a significant lesion of the coronaries is found.[9] CABG can be employed in other situations other than atheromatic disease of native heart arteries. Dissections of coronary arteries (a rupture of the coronary layers creates a pseudo-lumen and diminishes blood delivery to the heart) that can be caused because of various reasons (pregnancy, tissue diseases as Enhler Danlos, Marfan Syndrome, cocaine abuse or Percutaneous coronary Intervention). Aneurysm of the coronaries is another reason for CABG, for it might cause thrombus within the vessel that can be spread further.[10]

CABG vs PCI

CABG and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) are the two modalities the medical community has to revascularize stenotic lesions of the cardiac arteries. Which one is preferable for each patient is still a matter of debate, but it is clear that in the presence of complex lesions, significant Left Main Disease and in diabetic patients, CABG seems to offer better results to patients than PCI.[11][10] Strong indications for CABG also include symptomatic patients and in cases where LV function is impaired.[10], CABG offers better results that PCI in left main disease and in multivessel CAD, because of the protection arterial conduits offer to the native arteries of the heart, by producing vasodilator factors and preventing advancement of atherotic plaques.[12] The question which modality has been studied in various trials. Patients with unprotected LM Disease (runoff of LM is not protected by a patent graft since previous CABG operation) were studied in NOBLE and EXCEL trials. NOBLE, which was published in 2016 is a multi-European country that found that CABG outperforms PCI in the long run (5 years). EXCEL, also published in 2016, found that PCI has similar results to CABG at 3 years, but this similarity fades at 4th year and later (CABG is better to PCI).[13][14]

Diabetic patients were studied in the FREEDOM trial, first published in 2012 and a follow up. It demonstrated a significant advantage in this group of patients when treated with CABG (vs PCI). The superiority was evident in a 3.8 year follow up and, an even further followup at 7.5 years, of the same patients documented again the superiority of CABG, enphasazing the benefits in smokers and younger patients.[15] BEST trial was published in 2015, comparing CABG and the latest technological advancement of PCI, second generation Drug-eluting stents in multivessel disease. Their results were indicative of CABG being a better option for patients with CAD.[16] A trial published in 2021 (Fractional Flow Reserve versus Angiography for Multivessel Evaluation, FAME 3), also concluded that CABG is a safer option than PCI, when comparing results after one year from intervention.[17]

Complications

The most common complications of CABG are postoperative bleeding, heart failure, Atrial fibrillation (a form of arrhythmia), stroke, renal dysfunction, and sternal wound infections.[18]

Postoperative bleeding occurs in 2-5% of cases and might force the cardiac team to take the patient back to operating theatre to control the bleeding[19] The most common criterion for that is the amount blood drained by chest tubes, left after the operation. Re-operation addresses surgical causes of that bleeding, which might originate from the aorta, the anastomosis or a branch of the conduit insufficiently sealed or from the sternum. Medical causes of bleeding include platelet abnormalities or coagulopathy due to bypass or the rebound heparin effect (heparin administered at the beginning of CPB reappears at blood after its neutralization by protamine).[20]

As for heart failure, low cardiac output syndrome (LCOS) can occur up to 14% of CABG cases and is according to its severity, is treated with inotropes, IABP, optimization of pre- and afterload, or correction of blood gauzes and electrolytes. The aim is to keep a systolic blood pressure above 90mmHg and cardiac index (CI) more than 2.2 L/min/m2.[18] LCOS is often transient.[19] Postoperative Myocardial infarction can occur because of either technical or patients factors- it's incidence is hard to estimate though due to various definitions, but most studies place it between 2 and 10%.[18] New ECG features as Q waves and/or US documented alternation of cardiac wall motions are indicative. Ongoing ischemia might prompt emergency angiography or re-operation.[19] Arrhythmias can also occur, most commonly atrial fibrillation (20-40%) that is treated with correcting electrolyte balance, rate and rhythm control.[19][18]

Various neurological adverse effects can occur after CABG, with total incidence about 1,5%[19] they can manifest as type 1-focal deficits (such as stroke or coma) or type 2- global ones (such as delirium) . Inflammation caused by CPB, hypoperfusion or cerebral embolism.[18] Cognitive impairment has been reported in up to 80% cases after CABG at discharge and lasting up to 40% for a year. The causes are rather unclear, it seems CPB is not a suspect since even in CABG cases not including CPB (as in Off-Pump CABG), the incidence is the same, whilst PCI has the same incidence of cognitive decline as well.[18][21]

Infections are also a problem of the postoperative period. Sternal would infections (superficial or deep), most commonly caused by Staphylococcus aureus, can add to mortality. Harvesting of two mammary arteries is a risk factor since the perfusion of sternum is significantly impaired.[18] Pneumonia can also occur.[19] Complications from the GI track have been described, most commonly are caused by peri-operative medications.[21]

Procedure

Preoperative workup and strategy

Routine preoperative workup aims to check the baseline status of systems and organs other than heart. Thus a chest x-ray to check lungs, complete blood count, renal and liver function tests are done to screen for abnormalities. Physical examination to determine the quality of the grafts or the safety of removing them, such as varicosities in the legs, or the Allen test in the arm is performed to be sure that blood supply to the arm wont be disturbed critically.[22]

Administration of anticoagulants such as aspirin, clopidogrel, ticagrelol and others, is stopped serval days before the operation, to prevent excessive bleeding during the operation and in the following period. Warfarin is also stopped for the same reason and the patient starts being administered heparin products after INR falls below 2.0.[22][23]

After the angiogram is reviewed by the surgical team, targets are selected (that is, which native arteries will be bypassed and where the anastomosis should be placed). Ideally, all major lesions in significant vessels should be addressed. Most commonly, left internal thoracic artery (LITA; formerly, left internal mammary artery, LIMA) is anastomosed to left anterior descending artery (LAD) because the LAD is the most significant artery of the heart, since it supplies a larger portion of myocardium than other arteries.[23]

A conduit can be used to graft one or more native arteries. In the latter case, an end-to-side anastomosis is performed. In the former, utilizing a sequential anastomosis, a graft can then deliver blood to two or more native vessels of the heart.[23] Also, the proximal part of a conduit can be anastomosed to the side of another conduit (by a Y or a T anastomose) adding to the versality of options for the architecture of CABG. It is preferred not to harvest too much length of conduits since it might cause some patients to need re-operation.[23]

With CBP (on-pump)

The patient is brought to the operating theatre, intubated and lines (e.g., peripheral IV cannulae; central lines such as internal jugular cannulae) are inserted for drug administration and monitoring. The traditional way of a CABG follows:

- Harvesting

A sternotomy is made, while conduits are being harvested (either from the arm or the leg). Then LITA (formerly, LIMA) is harvested through the sternotomy. There are two common ways of mobilizing the LITA, the pedicle (i.e., a pedicle consisting of the artery plus surrounding fat and veins) and the skeletonized (i.e., freed of other tissues). Before being divided in its more distal part, heparin is administered to the patient via a peripheral line (for clot prevention).[23]

- Catheterization and establishment of cardiopulmonary bypass (on-pump)

After harvesting, the pericardium is opened and stay sutures are placed to keep it open. Purse string sutures are placed in aorta to prepare the insertions of the aortic cannula and the catheter for cardioplegia (a solution high in potassium that serves to arrest the heart). Another purse string is placed in right atrium for the venous cannula. Then the cannulas and the catheter are placed, cardiopulmonary bypass is commenced (venous deoxygenated blood arriving to the heart is forwarded to the CBP machine to get oxygenated and delivered to aorta to keep rest of the body saturated, and often cooled to 32 - 34 degrees celsius in order to slow down the metabolism and minimize as much as possible the demand for oxygen. A clamp is placed on the Aorta between the cardioplegic catheter and aortic cannula, so the cardioplegic solution that the flow is controlled by the surgeon that clamps Aorta. Within minutes, heart stops beating.[23][24]

- Anastomosis (grafting)

With the heart still, the tip of the heart is taken out of pericardium, so the native arteries lying in the posterior side of the heart are accessible. Usually, distal anastomosis are constructed first (first to right coronary system, then to the circumflex) and then the sequential anastomosis if necessary. Surgeons check the anastomosis for patency or leaking and if everything is as it should be, surgeons insert the graft within the pericardium, sometimes attached to the cardioplegic catheter. The anastomosis of LIMA to LAD is usually the last one of the distal anastomoses to be constructed, while it is being constructed the rewarming process starts (by the CPB).[23]. After the anastomosis is completed and checked for leaks, the proximal anastomoses of the conduits, if any, are next. They can be done either with the clamp still on or after removing the aortic clamp and isolating a small segment of the aorta by placing a partial clamp (but atheromatic aortas might be damaged by overhandling them; atheromatic derbis might get detached and cause embolization in end organs)[23][25]

- Weaning from cardiopulmonary bypass and closure

After the proximal anastomoses are done, the clamp is removed, aorta and conduits deaired, pacing wires might be placed if indicated and if the heart and other systems are functioning well CBP is discontinued, cannulas removed and protamine is administered to reverse the effect of heparin . After possible bleeding sites are checked, chest tubes are placed and sternum is closed.[23][25]

Off-pump (OPCABG)

Off-pump coronary artery bypass graft (OPCABG) surgery avoids using CPB machine by stabilizing small segments of the heart. It takes great care and coordination among the surgical team and anesthesiologists to not manipulate the heart too much so hemodynamic stability will not be compromised; however, if it is compromised, it should be detected immediately and appropriate action should be taken.

To keep heart beating effectively, some maneuvers can take place like placing atrial wires to protect from bradycardia, placing stitches or incisions to pericardium to help exposure. Snares and tapes are used to facilitate exposure. the aim is to avoid distal ischemia by occluding the vessel supplying distal portions of the left ventricle, so usually LIMA to LAD is the first to be anastomosed and others follow. For the anastomosis, a fine tube blowing humidified CO2 is used to keep the surgical field clean of blood. Also, a shunt might be used so the blood can travel pass the anastomotic site. After the distal anastomosis are completed, proximal anastomosis to the aorta are constructed with a partially aortic clamp and rest is similar with on-pump CABG.[26]

Alternative approaches and special situations

When CABG is performed as an emergency because of hemodynamic compromise after an infraction, priority is to salvage the struggling myocardium. Pre-operatively, an intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) might be inserted to relieve some of the burden of pumping blood, effectively reducing the amount of oxygen needed by myocardium. Operatively, the standard practice is to place the patient on CPB as soon as possible and revascularize the heart with three saphenous veins. Calcified aorta also poses a problem since it is very dangerous to clamp. In this case, the operation can be done as off-pump CAB utilizing both IMAs or Y, T and sequential grafts, or in deep hypothermic arrest, that is lower the temperature of the body to little above 20 Celsius, can also force the heart stop moving.[27] In cases were a significant artery is totally occluded, there's a possibility to remove the atheroma, and using the same hole in the artery to perform an anastomosis ·this technique is called endarterectomy and is usually performed at the Right Coronary System.[28]

Reoperations of CABG (another CABG operation after a previous one), poses some difficulties: Heart may be too close to the sternum and thus at risk when cutting the sternum again, so an oscillating saw is used. Heart may be covered with strong adhesions to adjusting structures, adding to the difficulty of the procedure. Also, aging grafts pose a dilemma, whether they should be replaced with new ones or not. Manipulation of vein grafts risks dislodgement of atheromatic debris and is avoided.[29]

"Minimally Invasive revascularization" (commonly MIDCAB form minimally invasive direct coronary artery bypass) is a technique that strives to avoid a large sternotomy. It utilizes off pump techniques to place a graft, usually LIMA at LAD. LIMA is monilized through a left thoracotomy, or even endoscopically through a thoracoscope placed in the left chest.[30] Robotic Coronary revascularization avoids the sternotomy to prevent infections and bleeding. Both conduit harvesting and the anastomosis are performed with the aid of a robot, through a thoracotomy. There is still no widespread use of the technique though. Usually it is combined with Hybrid Coronary Revascularization, which is the strategy where combined methods of CABG and PCI are employed. LIMA to LAD is performed in the operating theatre and other lesions are treated with PCI, either at the operating room, right after the anastomosis or serval days later.[31]

Illustration depicting coronary artery bypass surgery (double bypass)

Illustration depicting coronary artery bypass surgery (double bypass) Illustration of Single bypass

Illustration of Single bypass Illustration of Double bypass

Illustration of Double bypass Illustration of Triple bypass

Illustration of Triple bypass Illustration of Quadruple bypass

Illustration of Quadruple bypass

After the procedure

After the procedure, usually patient is transferred to the intensive care unit, where he is extubated if that hadn't already happen in the operating theatre. The following day exits the ICU and 4 days later, if no complication occurs, patient is discharged from the hospital.[32]

A series of drugs are commonly used in the early postoperative period. Dobutamine, a beta agent, can be used to increase the cardiac output that sometimes occurs some hours after the operation. Beta blockers are used to prevent atrial fibrillation and other supraventricular arrhythmias. Biatrial pacing through the pacing wires inserted at operation might help towards preventing atrial fibrillation. Aspirin 80mg is used to prevent graft failure.[32] Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are used to control blood pressure, especially in patients with low cardiac function (<40%). Amlodipine, a calcium channel blocker, is used for patients that radial artery was used as a graft.[2]

After the discharge, patients might suffer from insomnia, low appetite, sex drive, memory and other likewise symptoms, this effect is usually transient and lasts about 6 to 8 weeks.[32] A tailored exercise plan will benefit the patient.[32]

Results

CABG is the best procedure to reduce mortality from severe CAD and improve quality of life.

Operative mortality relates strongly to age of patient. According to a study by Eagle et al, for patients 50-59 years old there's an operative mortality rate of 1.8% while patients older than 80, the risk is 8.3%.[33] Other factors which increase mortality are: female gender, re-operation, dysfunction of Left ventricle and left main disease.[33] In most cases, CABG relieves angina, but in some patients it reoccurs in a later stage of their lives. Around 60% of patient will be angina free, 10 years after their operation.[33] Myocardial infarction is rare 5 years after a CABG, but its prevalence increases with time.[34] Also, the risk of sudden death is low for CABG patients.[34] Quality of life is also high for at least 5 years, then starts to decline.[35]

The beneficial effects of CABG are clear at cardiac level. LV function is improved and malfunctioning segments of the heart (dyskinetic-moving inefficiently or even akinetic-not moving) can show signs of improvement. Both systolic and diastolic functions are improved and keep improving for up to 5 years in some cases.[36] LV function, and myocardial perfusion, during exercise also improves after CABG. But when the LV function is severely impaired before operation (EF<30%), the benefits at the heart are less impressive in terms of segmental wall movement, but still significant since other parameters might improve as LV functions improves, the pulmonary hypertension might be relieved and survival prolongs.[36][18]

It is hard to determine the total risk of the procedure since the group of patients undergoing CABG is a heterogenic one, hence various subgroups have different risk, but it seems like the results for younger patients are better. Also, a CABG with two rather one internal mammary arteries seems to offer greater protection from CAD but results are not yet conclusive.[33][21]

Grafts

Various conduits can be utilized for CABG- they fall into two main categories, arteries and veins. Arteries have a superior long term patency, but veins are still largely in use due to practicality.

Arterial grafts that can be used originate from the part of the Internal Mammary Artery (IMA) that runs near the edge of sternum and can easily be mobilized and anastomosed to the native target vessel of the heart. Left is most often used as it is closer to heart but Right IMA is utilized depending on patient and surgeon preferences. ITAs advantages are mostly due to their endothelial cells that produce factors (Endothelium-derived relaxing factor and prostacyclin) that protect the artery from atherosclerosis and thus stenosis or occlusion. But using two ITAs has drawbacks, high rate of specific complications (deep sternal wound infections) in some subgroups of patients, mainly in obese and diabetic ones. Left radial artery and left Gastroepiploic artery can be used as well. Long term patency is influenced by the type of artery used, as well as intrinsic factors of the cardiac arterial circulation.[37]

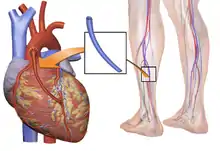

Venous grafts used are mostly great saphenous veins and in some cases lesser saphenous vein. Their patency rates is lower than arteries. Aspirin protects grafts from occlusion but adding clopidogrel does not improve rates.[37]

CABG vs PCI

CABG and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) are the two modalities the medical community has to revascularize stenotic lesions of the cardiac arteries. Which one is preferable for each patient is still a matter of debate, but it is clear that in the presence of complex lesions, significant Left Main Disease and in diabetic patients, CABG seems to offer better results to patients than PCI.[11][10] Strong indications for CABG also include symptomatic patients and in cases where LV function is impaired.[10]

History

Pre-CABG

Surgical interventions aiming relieve angina and prevent death in the early 20th century, were either sympatheticectomy (a cut on the sympathetic chain that supplies the heart, with disappointing and inconsistent results) or pericardial abrasion (with the hope that adhesions would create significant collateral circulation).[39]French Surgeon Alexis Carrel was the first to anastomose a vessel (a branch of carotid artery) to a native artery in the Heart, in a canine model- but because of technical difficulties the operation could not be reproduced.[40] In mid 20th century, revascularization efforts continued. Beck CS, used a carotid conduit to connect descending aorta to coronary sinus -the biggest vein of the heart, while Arthur Vineberg used skeletonized LIMA, placing it in a small tunnel he created next to LAD (known "Vineberg Procedure"), with the hope of spontaneous collateral circulation would form, and it did in canine experiments but was not successful in humans. Goetz RH was the first to perform an anastomosis of the IMA to LAD in the 1960 utilizing a sutureless technique.[39]

The development of coronary angiography in 1962 by Mason Sones, helped medical doctors to identify both patients that are in need of operation, but also which native heart vessels should be bypassed.[41] In 1964, Soviet cardiac surgeon, Vasilii Kolesov, performed the first successful internal mammary artery–coronary artery anastomosis, followed by Michael DeBakey in the USA. But it was René Favaloro that standarized the procedure. Their advances made CABG as the standard of care of CAD patients.[42]

The CABG era

The "modern" era of the CABG begun in 1964 with Soviet cardiac surgeon, Vasilii Kolesov, performed the first successful internal mammary artery–coronary artery anastomosis in 1964, while Michael DeBakey used a saphenous vein to create an aorta-coronary artery bypass. Argentinean surgeon Rene Favaloro, advanced and standardized CABG technique using saphenous vein.[42]

Introduction of cardioplegia helped CABG to became a much less risky operation. A major obstacle of CABG during those times, was the ischemia and Infraction, while the heart was still to allow surgeons to construct the distal anastomosis. In the 1970's, potassium cardioplegia was utilized. Cardioplegia minimized the oxygen demands of heart, thus the effects of ischemia also minimized. Refinement of cardioplegia in the 1980's made CABG less risky (lowering perioperative mortality) and thus a more attractive option when dealing with CAD.[43]

In the late 1960's, after the work of Rene Favaloro, the operation was still performed in a few centers of excellence, but was anticipated to change the landscape of Coronary Artery Disease, a significant killer in the developed world. More and more centers begun performing CABG resulting in 114 000 procedures/year in the USA by 1979. Invention of PCI didnt halt the CABG, numbers of both procedures continued to increase, albeit PCI's more rapidly. The following decades, CABG was studied and compared to PCI extensively. The absence of a clear advantage of CABG over PCI led to a small decrease in numbers of CABG in some countries (like the USA) in the turning of the new millennium but in European countries, CABG was increasingly performed (mainly in Germany). Research is still ongoing on CABG vs PCI.[44]

In the history graft selection, again the work of Favaloro was fundumental. He established that the use of bilateral IMA's were superior that vein grafts. The following years, surgeons examined the use of other arterial grafts (splenic, gastroepiploic mesenteric, subscupular and others) but none of these matched the patency rates of IMA. Carpentier in 1971 introduced radial artery, which initially was prone to failure, but evolution of harvesting techniques the next two decades, improved the patency significantly.[45]

See also

References

- Al-Atassi et al. 2016, pp. 1553–1554.

- Al-Atassi et al. 2016, p. 1554.

- Kouchoukos et al. 2013, p. 405.

- Kouchoukos et al. 2013, p. 356.

- Kouchoukos et al. 2013, p. 357.

- Bojar 2021, pp. 4–9.

- Bojar 2021, pp. 7–10.

- Smith & Schroder 2016, p. 549.

- Al-Atassi et al. 2016, p. 1556.

- Kouchoukos et al. 2013, p. 409.

- Welt 2022, pp. 185–186.

- Farina, Gaudino & Taggart 2020, pp. 1 & 6.

- Farina, Gaudino & Taggart 2020, pp. 1–2.

- Ngu, Sun & Ruel 2018, pp. 527–531.

- Farina, Gaudino & Taggart 2020, pp. 4–5.

- Ngu, Sun & Ruel 2018, pp. 529.

- Fearon et al. 2022, pp. 128–129.

- Al-Atassi et al. 2016, Results.

- Smith & Schroder 2016, p. 565.

- Al-Atassi et al. 2016, 1569.

- Smith & Schroder 2016, p. 566.

- Al-Atassi et al. 2016, Surgical Technique.

- Kouchoukos et al. 2013, p. 367.

- Al-Atassi et al. 2016, p. 1562.

- Al-Atassi et al. 2016, p. 1564.

- Kouchoukos et al. 2013, pp. 374–376.

- Al-Atassi et al. 2016, p. 1563.

- Kouchoukos et al. 2013, p. 348.

- Kouchoukos et al. 2013, p. 386.

- Mick et al. 2016, pp. 1603–1605.

- Mick et al. 2016, pp. 1606–1608.

- Kouchoukos et al. 2013, p. 387.

- Kouchoukos et al. 2013, p. 388.

- Kouchoukos et al. 2013, p. 397.

- Kouchoukos et al. 2013, p. 399.

- Kouchoukos et al. 2013, p. 401.

- Kouchoukos et al. 2013, p. 403.

- Al-Atassi et al. 2016, p. 1552.

- Head et al. 2013, pp. 2862–2863.

- Al-Atassi et al. 2016, p. 1551.

- Head et al. 2013, p. 2862.

- Head et al. 2013, p. 2863.

- Head et al. 2013, p. 2865.

- Head et al. 2013, pp. 2863–2865.

- Head et al. 2013, p. 2868.

Sources

- Al-Atassi, Talal; Toeg, Hadi D.; Chan, Vincent; Ruel, Marc (2016). "Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting". In Frank Sellke; Pedro J. del Nido (eds.). Sabiston and Spencer Surgery of the Chest. ISBN 978-0-323-24126-7.

- Bojar, R.M. (2021). Manual of Perioperative Care in Adult Cardiac Surgery. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-119-58255-7. Retrieved 2022-10-26.

- Farina, Piero; Gaudino, Mario Fulvio Luigi; Taggart, David Paul (2020). "The Eternal Debate With a Consistent Answer: CABG vs PCI". Seminars in Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. Elsevier BV. 32 (1): 14–20. doi:10.1053/j.semtcvs.2019.08.009. ISSN 1043-0679. S2CID 201632303.

- Fearon, William F.; Zimmermann, Frederik M.; De Bruyne, Bernard; Piroth, Zsolt; van Straten, Albert H.M.; Szekely, Laszlo; Davidavičius, Giedrius; Kalinauskas, Gintaras; Mansour, Samer; Kharbanda, Rajesh; Östlund-Papadogeorgos, Nikolaos; Aminian, Adel; Oldroyd, Keith G.; Al-Attar, Nawwar; Jagic, Nikola; Dambrink, Jan-Henk E.; Kala, Petr; Angerås, Oskar; MacCarthy, Philip; Wendler, Olaf; Casselman, Filip; Witt, Nils; Mavromatis, Kreton; Miner, Steven E.S.; Sarma, Jaydeep; Engstrøm, Thomas; Christiansen, Evald H.; Tonino, Pim A.L.; Reardon, Michael J.; Lu, Di; Ding, Victoria Y.; Kobayashi, Yuhei; Hlatky, Mark A.; Mahaffey, Kenneth W.; Desai, Manisha; Woo, Y. Joseph; Yeung, Alan C.; Pijls, Nico H.J. (2022-01-13). "Fractional Flow Reserve–Guided PCI as Compared with Coronary Bypass Surgery". New England Journal of Medicine. Massachusetts Medical Society. 386 (2): 128–137. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2112299. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 34735046. S2CID 242940936.

- Head, S. J.; Kieser, T. M.; Falk, V.; Huysmans, H. A.; Kappetein, A. P. (2013-10-01). "Coronary artery bypass grafting: Part 1--the evolution over the first 50 years". European Heart Journal. Oxford University Press (OUP). 34 (37): 2862–2872. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/eht330. ISSN 0195-668X. PMID 24086085.

- Smith, Peter K.; Schroder, Jacob N. (2016). "On-Pump Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting". In Josef E. Fischer (ed.). Master Techniques in Surgery CARDIAC SURGERY. ISBN 9781451193534.

- Kouchoukos, Nicholas; Blackstone, E. H.; Hanley, F. L.; Kirklin, J. K. (2013). Kirklin/Barratt-Boyes Cardiac Surgery E-Book (4th ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4160-6391-9.

- Mick, Stephanie; Keshavamurthy, Suresh; Mihaljevicl, Tomislav; Bonatti, Johannes (2016). "Robotic and Alternative Approaches to Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting". In Frank Sellke; Pedro J. del Nido (eds.). Sabiston and Spencer Surgery of the Chest. pp. 1603–1615. ISBN 978-0-323-24126-7.

- Ngu, Janet M. C.; Sun, Louise Y.; Ruel, Marc (2018). "Pivotal contemporary trials of percutaneous coronary intervention vs. coronary artery bypass grafting: a surgical perspective". Annals of Cardiothoracic Surgery. AME Publishing Company. 7 (4): 527–532. doi:10.21037/acs.2018.05.12. ISSN 2225-319X. PMC 6082775. PMID 30094218.

- Welt, Frederick G.P. (2022-01-13). "CABG versus PCI — End of the Debate?". New England Journal of Medicine. Massachusetts Medical Society. 386 (2): 185–187. doi:10.1056/nejme2117325. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 35020989.

External links

- Lawton JS, Tamis-Holland JE, Bangalore S, Bates ER, Beckie TM, Bischoff JM, Bittl JA, Cohen MG, DiMaio JM, Don CW, Fremes SE, Gaudino MF, Goldberger ZD, Grant MC, Jaswal JB, Kurlansky PA, Mehran R, Metkus TS Jr, Nnacheta LC, Rao SV, Sellke FW, Sharma G, Yong CM, Zwischenberger BA. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI guideline for coronary artery revascularization: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79:e21-e129