Pelvic organ prolapse

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is characterized by descent of pelvic organs from their normal positions. In women, the condition usually occurs when the pelvic floor collapses after gynecological cancer treatment, childbirth or heavy lifting.[2]

| Pelvic organ prolapse | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Female genital prolapse |

| Specialty | Gynecology |

| Frequency | 316 million women (9.3% as of 2010)[1] |

In men, it may occur after the prostate gland is removed. The injury occurs to fascia membranes and other connective structures that can result in cystocele, rectocele or both. Treatment can involve dietary and lifestyle changes, physical therapy, or surgery.[3]

Types

- Anterior vaginal wall prolapse

- Cystocele (bladder into vagina)

- Urethrocele (urethra into vagina)

- Cystourethrocele (both bladder and urethra)

- Posterior vaginal wall prolapse

- Enterocele (small intestine into vagina)

- Rectocele (rectum into vagina)

- Sigmoidocele

- Apical vaginal prolapse

- Uterine prolapse (uterus into vagina)[4]

- Vaginal vault prolapse (roof of vagina) – after hysterectomy

Grading

Pelvic organ prolapses are graded either via the Baden–Walker System, Shaw's System, or the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) System.[5]

Shaw's System

Anterior wall

- Upper 2/3 cystocele

- Lower 1/3 urethrocele

Posterior wall

- Upper 1/3 enterocele

- Middle 1/3 rectocele

- Lower 1/3 deficient perineum

Uterine prolapse

- Grade 0 Normal position

- Grade 1 descent into vagina not reaching introitus

- Grade 2 descent up to the introitus

- Grade 3 descent outside the introitus

- Grade 4 Procidentia

Baden–Walker

| Grade | Posterior urethral descent, lowest part other sites |

|---|---|

| 0 | normal position for each respective site |

| 1 | descent halfway to the hymen |

| 2 | descent to the hymen |

| 3 | descent halfway past the hymen |

| 4 | maximum possible descent for each site |

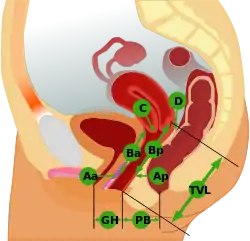

POP-Q

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 | No prolapse anterior and posterior points are all −3 cm, and C or D is between −TVL and −(TVL−2) cm. |

| 1 | The criteria for stage 0 are not met, and the most distal prolapse is more than 1 cm above the level of the hymen (less than −1 cm). |

| 2 | The most distal prolapse is between 1 cm above and 1 cm below the hymen (at least one point is −1, 0, or +1). |

| 3 | The most distal prolapse is more than 1 cm below the hymen but no further than 2 cm less than TVL. |

| 4 | Represents complete procidentia or vault eversion; the most distal prolapse protrudes to at least (TVL−2) cm. |

Management

Vaginal prolapses are treated according to the severity of symptoms.

Non-surgical

With conservative measures, such as changes in diet and fitness, Kegel exercises, and pelvic floor physical therapy.[7]

With a pessary, a rubber or silicone rubber device fitted to the patient which is inserted into the vagina and may be retained for up to several months. Pessaries are a good choice of treatment for women who wish to maintain fertility, are poor surgical candidates, or who may not be able to attend physical therapy.[8] Pessaries require a provider to fit the device, but most can be removed, cleaned, and replaced by the woman herself. Pessaries should be offered to women considering surgery as a non-surgical alternative.

Surgery

With surgery (for example native tissue repair, biological graft repair, absorbable and non-absorbable mesh repair, colpopexy, colpocleisis). Surgery is used to treat symptoms such as bowel or urinary problems, pain, or a prolapse sensation. Evidence does not support the use of transvaginal surgical mesh compared with native tissue repair for anterior compartment prolapse owing to increased morbidity.[9] For posterior vaginal repair, the use of mesh or graft material does not seem to provide any benefits.[10] Safety and efficacy of many newer meshes is unknown.[9] The use of a transvaginal mesh in treating vaginal prolapses is associated with side effects including pain, infection, and organ perforation. Transvaginal repair seems to be more effective than transanal repair in posterior wall prolapse, but adverse effects cannot be excluded.[10] According to the FDA, serious complications are "not rare."[11] A number of class action lawsuits have been filed and settled against several manufacturers of TVM devices.

Compared to native tissue repair, transvaginal permanent mesh probably reduces women's perception of vaginal prolapse sensation and probably reduces the risk of recurrent prolapse and of having repeat surgery for prolapse. On the other hand, transvaginal mesh probably has a greater risk of bladder injury and of needing repeat surgery for stress urinary incontinence or mesh exposure.[12] When operating a pelvic organ prolapse, introducing a mid-urethral sling during or after surgery seems to reduce stress urinary incontinence.[13]

Epidemiology

Genital prolapse occurs in about 316 million women worldwide as of 2010 (9.3% of all females).[1]

Research

To study POP, various animal models are employed: non-human primates, sheep,[14][15] pigs, rats, and others.[16][17]

See also

References

- Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, Ezzati M, et al. (December 2012). "Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2163–2196. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. PMC 6350784. PMID 23245607.

- Ramaseshan AS, Felton J, Roque D, Rao G, Shipper AG, Sanses TV (April 2018). "Pelvic floor disorders in women with gynecologic malignancies: a systematic review". International Urogynecology Journal. 29 (4): 459–476. doi:10.1007/s00192-017-3467-4. PMC 7329191. PMID 28929201.

- "Pelvic organ prolapse". womenshealth.gov. 2017-05-03. Retrieved 2017-12-29.

- Donita D (2015-02-10). Health & physical assessment in nursing. Barbarito, Colleen (3rd ed.). Boston. p. 665. ISBN 978-0-13-387640-6. OCLC 894626609.

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology (September 2007). "ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 85: Pelvic organ prolapse". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 110 (3): 717–729. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000263925.97887.72. PMID 17766624.

- Beckley I, Harris N (2013-03-26). "Pelvic organ prolapse: a urology perspective". Journal of Clinical Urology. 6 (2): 68–76. doi:10.1177/2051415812472675. S2CID 75886698.

- "Kegel Exercises | NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Retrieved 2017-12-02.

- Tulikangas P, et al. (Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology and the American Urogynecologic Society) (April 2017). "Practice Bulletin No. 176: Pelvic Organ Prolapse". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 129 (4): e56–e72. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000002016. PMID 28333818. S2CID 46882949.

- Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, Christmann-Schmid C, Haya N, Brown J (November 2016). "Surgery for women with anterior compartment prolapse". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (11): CD004014. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004014.pub6. PMC 6464975. PMID 27901278.

- Mowat A, Maher D, Baessler K, Christmann-Schmid C, Haya N, Maher C (5 March 2018). "Surgery for women with posterior compartment prolapse". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 (3): CD012975. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012975. PMC 6494287. PMID 29502352.

- "UPDATE on Serious Complications Associated with Transvaginal Placement of Surgical Mesh for Pelvic Organ Prolapse: FDA Safety Communication". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 13 July 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

- Maher, C; Feiner, B; Baessler, K; Christmann-Schmid, C; Haya, N; Marjoribanks, J (9 February 2016). "Transvaginal mesh or grafts compared with native tissue repair for vaginal prolapse". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2: CD012079. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012079. PMC 6489145. PMID 26858090.

- Baessler K, Christmann-Schmid C, Maher C, Haya N, Crawford TJ, Brown J (19 August 2018). "Surgery for women with pelvic organ prolapse with or without stress urinary incontinence". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 (8): CD013108. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013108. PMC 6513383. PMID 30121956.

- Patnaik SS, Brazile B, Dandolu V, Damaser M, van der Vaart CH, Liao J. "Sheep as an animal model for pelvic organ prolapse and urogynecological research" (PDF). ASB 2015 Annual Conference 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-03-27. Retrieved 2019-03-26.

- Patnaik SS (2015). Investigation of sheep reproductive tract as an animal model for pelvic organ prolapse and urogyencological research. Mississippi State University.

- Couri BM, Lenis AT, Borazjani A, Paraiso MF, Damaser MS (May 2012). "Animal models of female pelvic organ prolapse: lessons learned". Expert Review of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 7 (3): 249–260. doi:10.1586/eog.12.24. PMC 3374602. PMID 22707980.

- Patnaik SS (2016). Chapter Six - Pelvic Floor Biomechanics From Animal Models. Academic Press. pp. 131–148. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-803228-2.00006-4.