Vertiginous epilepsy

Vertiginous epilepsy is infrequently the first symptom of a seizure, characterized by a feeling of vertigo. When it occurs, there is a sensation of rotation or movement that lasts for a few seconds before full seizure activity. While the specific causes of this disease are speculative there are several methods for diagnosis, the most important being the patient's recall of episodes. Most times, those diagnosed with vertiginous seizures are left to self-manage their symptoms or are able to use anti-epileptic medication to dampen the severity of their symptoms.

Vertiginous epilepsy has also been referred to as epileptic vertigo, vestibular epilepsy, vestibular seizures, and vestibulogenic seizures in different cases, but vertiginous epilepsy is the preferred term.[1]

Signs and Symptoms

The signs of vertiginous epilepsy often occur without a change in the subject’s consciousness so that they are still aware while experiencing the symptoms.[2] It is often described as a sudden onset of feeling like one is turning in one direction, typically lasting several seconds.[2] Although subjects are aware during an episode, they often cannot remember specific details due to disorientation, discomfort, and/or partial cognitive impairment.[2] This sensation of rotational movement in the visual and auditory planes is also known as a vertiginous aura (symptom), which can precede a seizure or may constitute a seizure itself.[3] Auras are a “portion of the seizure that occur before consciousness is lost and for which memory is retained afterwards.”[4] Auras can be focused in different regions of the brain and can thus affect different functions. Some such symptoms that may accompany vertiginous epilepsy include:

Many people tend to mistake dizziness as vertigo, and although they sound similar, dizziness is not considered a symptom of vertiginous epilepsy. Dizziness is the sensation of imbalance or floating, impending loss of consciousness, and/or confusion.[2] This is different from vertigo which is characterized by the illusion of rotational movement [2] caused by the “conflict between the signals sent to the brain by balance- and position-sensing systems of the body”.[5]

Mechanism

Although a specific cause has not been identified to always induce vertiginous epilepsy there have been a number of supported hypotheses to how these seizures come about, the most common being traumatic injury to the head. Other causes include tumor or cancers in the brain, stroke with loss of blood flow to the brain, and infection. A less tested hypothesis that some believe may play a larger role in determining who is affected by this disease is a genetic mutation that predisposes the subject for vertiginous epilepsy.[4] This hypothesis is supported by occurrences of vertiginous epilepsy in those with a family history of epilepsy.[6]

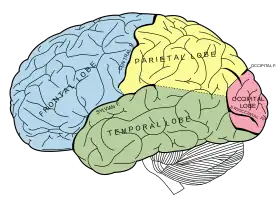

Vertiginous epilepsies are included in the category of the partial epilepsy in which abnormal electrical activity in the brain is localized.[3] With current research, it is presumed that the most likely cause to produce vertigo are epilepsies occurring in the lateral temporal lobe.[2] These abnormal electrical activities can either originate from within the temporal lobe or may propagate from an epilepsy in a neighboring region of the brain. Epilepsies in the parietal and occipital lobes commonly propagate into the temporal lobe inducing a vertiginous state.[2] This electrical propagation across the brain explains why so many different symptoms may be associated with the vertiginous seizure. The strength of the electrical signal and its direction of propagation in the brain will also determine which associated symptoms are noticeable.

Diagnosis

The most important factor in diagnosing a patient with vertiginous epilepsy is the subject’s detailed description of the episode.[2] However, due to the associated symptoms of the syndrome a subject may have difficulty remembering the specifics of the experience. This makes it difficult for a physician to confirm the diagnosis with absolute certainty. A questionnaire may be used to help patients, especially children, describe their symptoms. Clinicians may also consult family members for assistance in diagnosis, relying on their observations to help understand the episodes.[7] In addition to the description of the event, neurological, physical and hematologic examinations are completed to assist in diagnosis. For proper diagnosis, an otological exam (examination of the ear) should also be completed to rule out disorders of the inner ear, which could also be responsible for manifestations of vertigo.[8] This may include an audiological assessment and vestibular function test.[8] During diagnosis, history-taking is essential in determining possible causes of vertiginous epilepsy as well as tracking the progress of the disorder over time.[8]

Other means used in diagnosis of vertiginous epilepsy include:

- Electroencephalography (EEG)[3]

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)[3]

- Positron emission tomography (PET) [2]

- Neuropsychological testing[2]

The EEG measures electrical activity in the brain, allowing a physician to identify any unusual patterns. While EEGs are good for identifying abnormal brain activity is it not helpful in localizing where the seizure originates because they spread so quickly across the brain.[3] MRIs are used to look for masses or lesions in the temporal lobe of the brain, indicating possible tumors or cancer as the cause of the seizures.[2] When using a PET scan, a physician is looking to detect abnormal blood flow and glucose metabolism in the brain, which is visible between seizures, to indicate the region of origin.[2]

Management

There is no real way to prevent against vertiginous episodes out of the means of managing the disease. As head trauma is a major cause for vertiginous epilepsy, protecting the head from injury is an easy way to avoid possible onset of these seizures. With recent advances in science it is also possible for an individual to receive genetic screening, but this only tells if the subject is predisposed to developing the condition and will not aid in preventing the disease.[4]

There are a range of ways to manage vertiginous epilepsy depending on the severity of the seizures. For simple partial seizures medical treatment is not always necessary.[2] To the comfort of the patient, someone ailed with this disease may be able to lead a relatively normal life with vertiginous seizures. If, however, the seizures become too much to handle, antiepileptic medication can be administered as the first line of treatment.[2] There are several different types of medication on the market to deter epileptic episodes but there is no support to show that one medication is more effective than another.[2] In fact, research has shown that simple partial seizures do not usually respond well to medication, leaving the patient to self-manage their symptoms.[2] A third option for treatment, used only in extreme cases when seizure symptoms disrupt daily life, is surgery wherein the surgeon will remove the epileptic region.[2]

Epidemiology

Vertiginous epilepsy onset can happen between the ages of 4–50, although typically symptoms will begin occurring in adolescence or young adulthood.[4] Research studies have shown no inclination for this disease between sexes.

History

Caloric reflex testing was developed and used for testing vestibular function of deaf children and in diagnosis of childhood vertigo. A man named Barany (1902) published the first monograph on vestibular nystagmus that recognized the clinical usefulness of caloric responses. Barany's theory of production of the vestibulo-ocular reflex in caloric testing remains as the accepted explanation along with the description of nystagmus created by rotation in both adults and infants. Barany's work would later influence a researcher named Galebsky that would help him conclude that semicircular canals were functional at birth for both calorization and rotation. His work would also confirm that the eyelid of a newborn is raised in response to a vestibular as well as an auditory stimulus.[9]

In the late 19th century and early 20th century, Hughlings Jackson[10] and W.R. Gowers[11] recognized that episodes of dizziness were a symptom of epilepsy.[6] During this time, when epileptic symptoms were brought to the forefront of study, there was no distinction between dizziness and vertigo. Sir George Frederick (1868–1941), known for his work in pediatric rheumatoid arthritis referred to as Still’s disease, was the first to publish a description of episodic vertigo in children within the broad category of ‘headaches in children’ in 1924.[9] Until recently, it was not widely recognized that episodes of suspected dizziness might be caused by epilepsy.[6]

Research

There have been early and consistent strategies for measurement to better understand vertiginous epilepsy including caloric reflex test, posture and gait, or rotational experimentation.[9]

In Japan, Kaga et al prepared a longitudinal study of rotation tests comparing congenital deafness and children with delayed acquisition of motor system skills. They were able to demonstrate the development of post-rotation nystagmus response from the frequency of beat and duration period from birth to six years to compare to adult values. Overall, the study demonstrated that some infants from the deaf population had impaired vestibular responses related to head control and walking age. A side interpretation included the evaluation of the vestibular system in reference to matching data with age.[9]

Research in this area of medicine is limited due to its lacking need for urgent attention. But, the American Hearing Research Foundation (AHRF) conducts studies in which they hope to make new discoveries to help advance treatment of the disease and possibly one day prevent vertiginous seizures altogether.

References

- Nielsen, J. M., MD. "Tornado Epilepsy Simulating Ménière's Syndrome." Neurology 9.11 (1959): 794. Neurology. Web. 23 Mar. 2014. <http://www.neurology.org/content/9/11/794.extract>.

- Stern, John M. "Focal Vertiginous Epilepsy." Atlas of Epilepsies. (2010): 463–465. Print.

- Benbadis, Selim. Wolters Kluwer Health. (2013): Web. 23 Mar. 2014. <http://www.uptodate.com/contents/localization-related-partial-epilepsy-causes-and-clinical-features>.

- Ottman, R. United States. NCBI. Autosomal Dominant Partial Epilepsy with Auditory Features. Seattle: University of Washington, 2007. Web.

- "Dizziness: Lightheadedness and Vertigo Topic Overview." WebMD. N.p., 2 Jan 2013. Web. 23 Mar 2014. <http://www.webmd.com/brain/tc/dizziness-lightheadedness-and-vertigo-topic-overview>.

- Kogeorgos, J., D.F. Scott, and M Swash. "Epileptic Dizziness." British Medical Journal . 282. (1981): n. page.

- Erbek, Seyra H., Selim S. Erbek, Ismail Yilmaz, Ozgal Topal, Nuri Ozgirgin, Levent N. Ozluoglu, and Fusun Alehan. "Vertigo in childhood: A clinical experience ." International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 70. (2006): 1547–1554.

- Choung, Yun-Hoon, Keehyun Park, Sung-Kyun Moon, Chul-Ho Kim, and Sang Jun RYu. "Various causes and clinical characteristics in vertigo in children with normal eardrums." Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 67. (2003): 889–894.

- Snashall S. The history of balance in children: a review. Audiological Medicine [serial online]. October 2009;7(3):132–137. Available from: CINAHL with Full Text, Ipswich, MA.

- Jackson H., Diagnosis of epilepsy. Medical Times and Gazette 1879; 1:29.

- Gowers WR., The borderlands of epilepsy. London: Churchill, 1907: 40–75.