Wet market

A wet market (also called a public market[4] or a traditional market[5]) is a marketplace selling fresh foods such as meat, fish, produce and other consumption-oriented perishable goods in a non-supermarket setting, as distinguished from "dry markets" that sell durable goods such as fabrics, kitchenwares and electronics.[6][10] These include a wide variety of markets, such as farmers' markets, fish markets, and wildlife markets.[14] Not all wet markets sell live animals,[17] but the term wet market is sometimes used to signify a live animal market in which vendors slaughter animals upon customer purchase,[21] such as is done with poultry in Hong Kong.[22] Wet markets are common in many parts of the world,[26] notably in China, Southeast Asia, and South Asia. They often play critical roles in urban food security due to factors of pricing, freshness of food, social interaction, and local cultures.[27]

| Wet market | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A meat stall at a wet market in Hong Kong | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 傳統市場 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 传统市场 | ||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | chuántǒng shìchǎng | ||||||||||

| Jyutping | cyun4 tung2 si5 coeng4 | ||||||||||

| Literal meaning | traditional market | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 街市 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 街市 | ||||||||||

| Jyutping | gaai1 si5 | ||||||||||

| Literal meaning | street market | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Most wet markets do not trade in wild or exotic animals,[32] but some that do have been linked to outbreaks of zoonotic diseases including COVID-19, H5N1 avian flu, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and monkeypox.[36] Several countries have banned wet markets from holding wildlife.[33][37] Media reports that fail to distinguish between all wet markets and those with live animals or wildlife, as well as insinuations of fostering wildlife smuggling, have been blamed for fueling Sinophobia related to the COVID-19 pandemic.[40]

Background

Terminology

The term "wet market" came into common use in Singapore in the early 1970s when the government used it to distinguish such traditional markets from the supermarkets that had become popular there.[41] The term was added to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) in 2016, as a term used throughout Southeast Asia.[42] The OED's earliest cited use of the term is from The Straits Times of Singapore in 1978.[8]

The "wet" in "wet market" refers to the constantly wet floors due to the melting of ice used to keep food from spoiling,[41][43][44] the washing of meat and seafood stalls and the spraying of fresh produce that are common in wet markets.[16][20][43]

The term "public market" may be synonymous with "wet market",[1][2][3] although it may sometimes refer exclusively to state-owned and community-owned wet markets.[1][2][3] Wet markets may also be called "fresh food markets" and "good food markets" when referring to markets consisting of numerous competing vendors primarily selling fresh produce like fruits and vegetables.[9] The term "wet market" is frequently used to signify a live animal market that sells directly to consumers,[18][19] although the terms are not synonymous.[25][45]

Although the term "wet market" may refer to markets that sell wild animals and wildlife products, it is not synonymous with the term "wildlife market" which exclusively refers to markets that contain wildlife products.[29][25][28][30][45]

Types

The term "wet market", which specifies markets that sell fresh produce and meat, includes a broad variety of markets.[1][11] Wet markets can be categorized according to their ownership structure (privately owned, state-owned, or community-owned), scale (wholesale or retail), and produce (fruits, vegetables, slaughtered meat, or live animals).[1][11] They can be further subcategorized based on whether the meat inventory originates from domesticated or wild animals.[1][11]

Traditional wet markets are typically housed in temporary sheds, open-air sites,[1][46][47][16] or partially open commercial complexes,[48][25] while modern wet markets are housed in buildings often equipped with improved ventilation, freezing, and refrigeration facilities.[1][49][50]

Economic role

Wet markets are less dependent on imported goods than supermarkets due to their smaller volumes and lesser emphasis on consistency.[51] Wet markets have been described in a 2019 food security study as "critical for ensuring urban food security", particularly in Chinese cities.[1] The roles of wet markets in supporting urban food security include food pricing and physical accessibility.[1]

Academic papers in urban studies, studies on food distribution, and the Singapore National Environment Agency have noted lower prices, greater freshness of food, and the facilitation of both bargaining and social interaction as key reasons for the persistence of wet markets.[1][44][52][53] The persistence of wet markets has also been attributed to "culinary traditions that call for freshly slaughtered meat and fish as opposed to frozen meats".[44]

In developing countries with agriculture-based economies, fresh meat is mainly distributed through traditional wet markets or meat stalls.[54] Wet markets selling fresh meat are often attached to, or located near, slaughter facilities.[54]

Wildlife markets and zoonoses

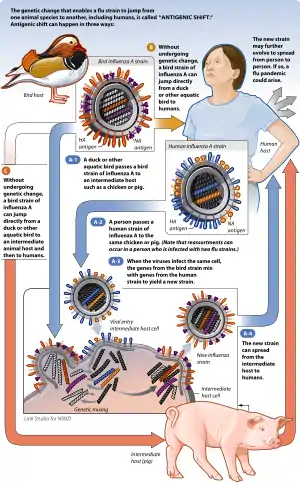

If sanitation standards are not maintained, wet markets can spread disease. Those that carry live animals and wildlife are at especially high risk of transmitting zoonoses. Because of the openness, newly introduced animals may come in direct contact with sales clerks, butchers, and customers or to other animals which they would never interact with in the wild. This may allow for some animals to act as intermediate hosts, helping a disease spread to humans.[34]

Outbreaks of zoonotic diseases including COVID-19, H5N1 avian flu, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and monkeypox have been traced to live wildlife markets where the potential for zoonotic transmission is greatly increased.[34][55][56][35] Wildlife markets in China have been implicated in the 2002 SARS outbreak; it is thought that the market environment provided optimal conditions for the coronaviruses of zoonotic origin that caused both outbreaks to mutate and subsequently spread to humans.[57] The exact origin of the COVID-19 pandemic is yet to be confirmed as of February 2021[58] and was originally linked to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan, China due to reports that two-thirds of the initial cases had direct exposure to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan.[59][60][61][62] although a 2021 WHO investigation concluded that the Huanan market was unlikely to be the origin due to the existence of earlier cases.[58]

Due to unhygienic sanitation standards and the connection to the spread of zoonoses and pandemics, critics have grouped live animal markets together with factory farming as major health hazards in China and across the world.[63][64][65][66] In March and April 2020, some reports have said that wildlife markets in Asia,[67][68][69] Africa,[70][71][72] and in general all over the world are prone to health risks.[73]

Disease control intervention

Due to the suspicions that wet markets could have played a role in the emergence of COVID-19, a group of US lawmakers, NIAID director Anthony Fauci, UNEP biodiversity chief Elizabeth Maruma Mrema, and CBCGDF secretary general Zhou Jinfeng called in April 2020 for the global closure of wildlife markets due to the potential for zoonotic diseases and risk to endangered species.[74][75][76][77] In April 2021, the World Health Organization called for a total ban on the sale of live animals in food markets in order to prevent future pandemics.[78]

Planetary health studies have called for disease control intervention measures, in lieu of outlawing live-animal wet markets, to be implemented in wet markets.[79][80][81] These include proposals for "standardised global monitoring of water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) conditions", which the World Health Organization announced in April 2020 that it was developing as requirements for wet markets to open.[79] Other proposals include less homogeneous policies that are specialized for local social, cultural, and financial factors,[81] as well as new proposed rapid assessment tools for monitoring the hygiene and biosecurity of live animal stalls in wet markets.[82]

Media coverage

During the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Chinese wet markets were heavily criticized in media outlets as a potential source for the virus.[62] Media reports urging for permanent blanket bans on all wet markets, as opposed to solely live animal markets or wildlife markets, have been criticized for undermining infection control needs to be specific about wildlife markets[11] and distracting public attention from local public health threats.[39] Some Western media portrayed wet markets without distinguishing between general wet markets, live animal wet markets, and wildlife markets,[83] using montages of explicit images from different markets across Asia without identifying locations.[11][25][84] These depictions have been criticized by other journalists and anthropologists as sensationalist, exaggerated, Orientalist, and fueling Sinophobia and "Chinese otherness".[11][25][38][39][84]

Around the world

There are wet markets throughout the world, with the largest concentration in Asia followed by Europe and North America according to touristic social network data in 2019.[85]

Ethiopia

According to a 2013 study on agricultural value chains, approximately 90% of households in Ethiopia across all income groups purchase their beef through local butchers in wet markets.[86][87]

Kenya

The most common agricultural supply chain in Kenya involves farmers selling their produce to collectors who then sell the produce to retailers in wet markets.[88] A 2006 study in the areas around Nairobi and Kisumu found that 21% of farmers sold to collectors, 17% sold directly to wholesalers, and 14% sold directly to wet market vendors.[88] The collectors and wholesalers both predominantly sold their produce inventory to wet market vendors.[88] The customers of the wet markets in the study were predominantly end consumers, although a small share of the wet markets also sold to restaurants.[88]

Nigeria

According to a 2011 USDA Foreign Agricultural Service report, most of the clientele of traditional open-air wet markets in Nigeria are low and middle income consumers.[89]

From 2008 to 2009, a group of food safety researchers launched an initiative working with a small group of butchers in the wet market section of Bodija Market in Ibadan to promote positive food safety practices and peer-to-peer training.[90][91] The initiative led to 20% more meat samples being of acceptable quality.[90][91] A follow-up study in 2019 on the same group of butchers found that, while many of the butchers still remembered the food safety practices, "none of the butchers reported that they continued to buy and replace the materials after the exhaustion of those distributed during the intervention programme".[90] The follow-up study found that the microbiological sanitation in 2018 was even worse than before the 2008–2009 intervention.[90]

In 2014, the license of the slaughterhouse in the wet market section of Bodija Market was revoked due to unhygienic meat handling practices.[90][92] In its place, the local government opened the Ibadan Central Abattoir in Amosun Village, Akinyele through public-private partnerships.[90][92] The new facility is equipped with modern facilities for slaughter and processing of meat were provided in 2014 through public-private partnerships and is one of the largest abattoirs in West Africa, consisting of 15 hectares of land with stalls for 1000 meat sellers, 170 shops, administrative building, clinic, canteen, cold room, and an incinerator.[90] In June 2018, local newspapers reported that five people were killed in the Bodija Market abattoir when a security team attempted to enforce the forcible relocation of Ibadan abattoirs to the new facilities as ordered by the local government.[90][93]

Uganda

The most common agricultural supply chain in Uganda involves farmers selling their produce to wholesalers, who in turn sell to retailers in wet markets.[88] A 2006 study in the areas around Kampala and Mbale found that 51% of farmers sold to wholesalers and 18% sold directly to wet market vendors, while 34% of the wholesalers sold to wet market vendors.[88] The customers of the wet markets in the study were predominantly end consumers, although a small share of the wet markets also sold to restaurants.[88]

Brazil

In Brazil, regulations on wet markets are handled at the municipal level.[94][95][96] The regulations widely vary across Brazil, with zoning rules prohibiting wet markets in some municipalities.[94][95]

A 2003 study found that wet markets were losing ground in food retail to supermarkets, which had an overall food retail market share of 75%.[96] The gains of supermarkets over traditional food retailers in Brazil were predominantly in meat and seafood retail, with the supermarkets' fresh meat & seafood market shares typically three times greater than their fresh fruits & vegetables market share.[96]

Colombia

According to a 2010 USDA Foreign Agricultural Service report, each small town in Colombia typically has a wet market that is supplied by local production and opens at least once a week.[97] The report described both retail wet markets and wholesale wet markets that provide food products for "Mom'n Pop stores".[97] It estimated the number of wet markets at around 2,000, but noted that the number was slowly decreasing in large cities despite the presence of large wet markets like Corabastos in Bogotá.[97]

Greenland

In Greenland, local wet markets known as brætter sell food from wild animals, including seal meat, whale meat, reindeer meat, and polar bear meat.[98] Brætter do not sell live animals, but most meat sold in brætter is fresh and recently butchered.[98] While larger towns have purpose-built facilities, the brætter in smaller towns and village settlements sell seafood in open-air stands without running water or electricity.[99] Only fresh meat was allowed to be sold in Nuuk at Kalaaliaraq Market, the largest fresh food market in Greenland, until 2018 when the government of Greenland began permitting the sale of dried and salted meat at Kalaaliaraq.[98]

Trichinosis is a common problem in Greenland due to the consumption of wild polar bear meat.[98][100] In 2016, several people were infected with Trichinella roundworms from eating polar bear meat from a local brætter even though the meat had initially passed inspections.[98][100] As of 2017, Trichinella inspections for seal and polar bear meat sold at brætter is not mandatory.[98]

Mexico

Some traditional Mexican open-air markets called tianguis, such as the Mercado Margarita Maza de Juárez in Oaxaca, are separated into a wet market (zona húmeda) and a dry market (zona seca).[101] A 2002 study observed a trend that Mexican consumers, especially those in the middle class, increasingly prefer supermarkets for beef purchases as opposed to traditional wet markets.[102][103] In 2014, a study of Mexican beef retail also noted an ongoing transition from traditional full-service wet markets to self-service meat display cases in supermarkets.[103]

In Mexico, conflicts between traditional and modern retailers are handled at the municipal and state levels.[94] Some local zoning rules, such as those in the central districts of Mexico City and Morelia, have prohibited wet markets from operating in urban districts without providing further assistance to the retailers.[94][95]

United States

In April 2020, The Hill reported that wet markets were still operating in the United States and that animal rights activists were calling for the closure of wet markets, in addition to their existing calls to close live animal markets and factory farms.[104]

Wet markets were common in New York City until refrigeration became commonplace in the 20th century.[45] From the 1990s to 2020, the number of live animal wet markets in New York City nearly doubled.[45] As of 2020, there are more than 80 wet markets in New York City that stock live animals and slaughter them on-demand for customers.[45][104] They are mostly poultry markets located in outer-borough immigrant communities where they are culturally significant and pose low public health risks relative to wildlife markets and other types of exotic wet markets.[45]

China

.jpg.webp)

Since the 1990s, large cities across China have moved traditional outdoor wet markets to modern indoor facilities.[47][1] As of 2018, wet markets remained the most prevalent food outlet in urban regions of China despite the rise of supermarket chains since the 1990s.[105] During the 2010s, "smart markets" equipped with e-payment terminals emerged as traditional wet markets faced increasing competition from discount stores.[106] Wet markets also began facing competition from online grocery stores, such as Alibaba's Hema stores.[20]

The trade of wildlife is not common in China, particularly in large cities,[20] and most wet markets in China do not contain live or wild animals besides fish held in tanks.[107] In the early 1980s, small-scale wildlife farming began under the Chinese economic reform.[108] It began to expand nationwide with government support in the 1990s, but was largely concentrated in the southeastern provinces.[108] In 2003, wet markets across China were banned from holding wildlife after the 2002–2004 SARS outbreak, which was directly tied to such practices.[33] Some poorly-regulated Chinese wet markets provided outlets for the wildlife trade industry after the ban, although the illegal wildlife trade in China was predominantly in fur rather than in food or medicine.[20][16][108] The Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan was linked to the origin of COVID-19 due to its early cluster of cases,[109][58] leading to further restrictions and enforcement in 2020.[16][29][110] In April 2020, the Chinese government unveiled plans to further tighten restrictions on wildlife trade.[20][16][108]

Hong Kong

_Market.jpg.webp)

Large centralised wet markets have existed in Hong Kong since at least 16 May 1842, when Central Market was opened.[111] Wet markets are most frequented by older residents, those with lower incomes, and domestic helpers who serve approximately 10 percent of Hong Kong's residents.[112] Most neighbourhoods contain at least one wet market.[20] Wet markets have become destinations for tourists to "see the real Hong Kong".[113]

Prior to 2000, many of Hong Kong's wet markets were managed by the Urban Council (within Hong Kong Island and Kowloon) or the Regional Council (in the New Territories). Since 2000, wet markets in Hong Kong have been regulated by the Food and Environmental Hygiene Department (FEHD).[114][115] Under the Slaughterhouse Regulation, the slaughtering of live bovine animals, swine, goats, sheep or soliped for human consumption must take place in a licensed slaughterhouse,[116] None of the wet markets in Hong Kong hold wild or exotic animals.[20]

In 2018, the FEHD operated 74 wet markets housing approximately 13,070 stalls.[114] In addition, the Hong Kong Housing Authority operated 21 markets while private developers operated about 99 (in 2017).[117]

India

The Indian meat, poultry, and seafood industries are largely dependent on wet markets.[118][119] According to Food & Beverage News, domestic consumers prefer freshly cut meat from wet markets over processed and frozen meats despite use of outdated and unhygienic facilities by the majority of Indian wet market abattoirs.[120]

In Delhi, the food retail system consists of the traditional informal food retail sector (wet markets, pushcarts, and kirana "mom-and-pop" stores), rent-free-subsidized retailers' cooperatives, government-owned food distribution channels, and private modern supermarkets.[121] Delhi wet markets generally consist of a number of small retailers that cluster together to sell their produce during daily fixed hours.[121] A 2010 study of Delhi food retail found that 68% to 75% of the total quantity of fruits and vegetables sold to consumers were distributed by wet market retailers.[121] The same study surveyed consumers at 518 wet market retailers in Delhi and found that their transactions included relatively little bargaining, with only a 3% average difference between the final price and the initially quoted price.[121]

Indonesia

Traditional wet markets, called pasars (including pasar malam and pasar pagi), are found across in Indonesia in both urban and rural areas. Wet markets face increasing competition from supermarkets as well as e-commerce companies like Shopee and Tokopedia.[49] As of 2020, there are 12.3 million traders across 13,450 wet markets in Indonesia.[5]

In 2016, the Indonesia government's policy to stabilise beef prices required importers to sell cheaper-priced meats in wet markets instead of in supermarkets and hypermarkets.[122] In Greater Jakarta, Indian buffalo meat is predominantly sold in wet markets, with limited market penetration from supermarkets and hypermarkets as of 2018.[122] In contrast, only 7% of consumers in Jakarta purchase Australian beef from supermarkets in 2018.[122] In 2018, Indonesian wet market vendors that import goods expressed concerns over the decrease in value of the Indonesian rupiah.[49]

Wet markets throughout Indonesia have undergone major renovations in the 2010s under a government program.[123] In 2018, the first modern wet market opened in Jakarta with a laboratory as well as freezing and refrigeration facilities.[49] Through June 2020, health protocols and mobility restrictions from the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia resulted in a 65% reduction in revenue for wet market traders, according to the Traditional Market Traders Association (IKAPPI).[5] In mid-2020, wet markets in several provinces accounted for several major clusters of COVID-19 cases.[124] An Airlangga University survey from May to June 2020 found that people in East Java wet markets followed health protocols, including social distancing and mask-wearing, the least relative to other public places in East Java.[124]

Malaysia

In March 2020, the Malaysian government temporarily banned the operation of all wet markets (including pasar malam and pasar pagi) as a national response to the coronavirus pandemic.[125]

Philippines

In the Philippines, wet markets are managed by cooperatives according to legislation such as the Cooperatives Code (RA 7160) and the Agriculture and Fisheries Modernization Act (RA 8435).[126] The Philippine government has control over the price of some commodities sold in palengkes, especially critical foods such as rice.[127][128]

In July 2017, the digital wet market Palengke Boy was launched in Davao City to compete against traditional wet markets.[129] In March 2020, the Pasig local government launched a mobile wet market to ensure access to basic goods during the COVID-19 pandemic.[130]

Singapore

Wet markets in Singapore are subsidized by the government.[49] The Tekka Market, Tiong Bahru Market, and Chinatown Complex Market are prominent wet markets containing seasonal fruit, fresh vegetables, imported beef, and live seafood.[131]

In the early 1990s, the slaughter of animals was banned in 12 inner-city markets and 22 wet market centers in Singapore.[132] In early 2020, the National Environment Agency issued advisories for "high standards of hygiene and cleanliness" for the 83 markets that it oversees in a response to the 2020 coronavirus pandemic.[44]

Sri Lanka

In Sri Lanka, where poultry is the leading livestock industry and constitutes the only meat export industry, the majority of broiler chickens are mechanically processed in semi-automated plants. However, poultry is still slaughtered in wet markets that generally cater to specific groups of customers and ethnic groups.[133] A 2017 study of 102 semi-automated poultry processing plants and 25 poultry-slaughtering wet markets found that 27.4% of the broiler neck skin samples from the semi-automated processing facilities tested positive for Campylobacter contamination, while 48% of broiler neck skin samples from the wet market processing facilities tested positive for Campylobacter contamination.[133]

Taiwan

.JPG.webp)

Many wet markets in Taiwan originated as groups of peddlers and roadside stalls that organized into informal physical structures.[134] By 2020, wet markets had been in decline throughout Taiwan for decades and revitalization efforts have been largely unsuccessful.[134]

In 1997, a report by the Taipei city government indicated that the city had 61 major wet markets with almost 10,000 registered vendors.[135] The report also indicated that most of the city's wet markets were in serious need of repair and that almost 3,500 of the vendor stalls lay vacant.[135] The Nanmen Market in Taipei is a government-owned traditional wet market that was opened in 1907 during the Japanese colonial rule.[50][135] The market building was demolished in October 2019 and the market temporarily relocated until its replacement modern 12-floor building is completed in 2022.[50]

One of the largest wet markets in Taiwan, the Jianguo Market in Taichung, was torn down and replaced by a new facility in 2016.[134] The new facilities provided better hygiene, disability accessibility, and refrigeration, but the relocation was initially met with hesitation from the local vendors before a grassroots outreach campaign led to greater acceptance.[134]

Thailand

Wet markets are the dominant preferred venue for grocery shopping in Thailand due to the local preference for fresh food,[136] as well as lower prices and familiarity with shopkeepers.[49]

United Arab Emirates

In October 2018, a Meat & Livestock Australia report said that while the United Arab Emirates's grocery retail sector is highly developed, wet markets are still prominent throughout the country.[122]

Vietnam

In 2017, there were approximately 9,000 wet markets, 800 supermarkets, 160 shopping malls and 1.3 million small family-owned stores across Vietnam according to government estimates.[137]

In 2017, the Hanoi city government planned to renovate the city's wet markets and transform them into modern shopping malls.[137] The plan was met with resistance from wet market vendors after significant declines in sales figures from other markets that were moved to the basements of high-end shopping centers.[137]

In 2020, Prime Minister of Vietnam Nguyễn Xuân Phúc announced proposals to ban wildlife trade in Vietnam.[37]

France

Rungis International Market in the Île-de-France region, created in 1969, is the largest market for fresh food in the whole of Europe, selling food from both within and without Île-de-France.[138] The largest wholesale food market in the world,[139] and perhaps even the largest fresh food market,[140] various foods are offered, including sheep[141] and eel.[142] By 1972, 6000 tonnes of fruits and vegetables were shipped to the market daily.[143]

Italy

The Porta Palazzo Market in the northwestern city of Turin is the largest street market in Europe,[144] having about a hundred fresh food producers sell their goods at the height of the season in the city's historic district.[145] The Turinese authorities, working alongside those of the market, have increasingly attempted to reconfigure the public's perception of the market as a multicultural space and a site for tourism, featuring cuisine from around the world.[146]

Ireland

The Iveagh Markets in Dublin, Ireland was an indoor market that was divided into a dry market that sold clothes and a wet market that sold fish, fruit, and vegetables.[147][148][149] The market operated from 1906 and had become dilapidated by the 1980s.[148][149] The last stalls closed in the 1990s and the building is still derelict as of 2018 despite failed attempts to redevelop the site into a new food market complex.[148][149][147]

Australia

In 2020, SBS reported that wet markets were once common in Australia and were gradually shut down over time as abattoirs were centralised and moved away from cities.[150] Media outlets Daily Mercury and Herald Sun, as well as Agriculture Minister David Littleproud and Leader of the Labor Party Anthony Albanese, have described various fresh meat, seafood, and produce markets in Australia, such as the Sydney Fish Market and Melbourne Fish Market, as wet markets in response to international calls to ban wet markets.[151][152][153][154]

See also

- Animal–industrial complex

- Bazaar

- Pasar malam

- Meat market

- Night market

- Ye wei (southern China)

References

- Zhong, Taiyang; Si, Zhenzhong; Crush, Jonathan; Scott, Steffanie; Huang, Xianjin (2019). "Achieving urban food security through a hybrid public-private food provisioning system: the case of Nanjing, China". Food Security. 11 (5): 1071–1086. doi:10.1007/s12571-019-00961-8. ISSN 1876-4517. S2CID 199492034.

- Morales, Alfonso (2009). "Public Markets as Community Development Tools". Journal of Planning Education and Research. 28 (4): 426–440. doi:10.1177/0739456X08329471. ISSN 0739-456X. S2CID 154349026.

- Morales, Alfonso (2011). "Marketplaces: Prospects for Social, Economic, and Political Development". Journal of Planning Literature. 26 (1): 3–17. doi:10.1177/0885412210388040. ISSN 0885-4122. S2CID 56278194.

- [1][2][3]

- Atika, Sausan (15 June 2020). "Indonesian wet markets carry high risk of virus transmission". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- Lin, Bing; Dietrich, Madeleine L; Senior, Rebecca A; Wilcove, David S (June 2021). "A better classification of wet markets is key to safeguarding human health and biodiversity". The Lancet Planetary Health. 5 (6): e386–e394. doi:10.1016/s2542-5196(21)00112-1. ISSN 2542-5196. PMC 8578676. PMID 34119013.

- Wholesale Markets: Planning and Design Manual (Fao Agricultural Services Bulletin) (No 90)

- "wet, adj". Oxford English Dictionary. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

wet market n. South-East Asian a market for the sale of fresh meat, fish, and produce

- Brown, Allison (2001). "Counting Farmers Markets". Geographical Review. 91 (4): 655–674. doi:10.2307/3594724. JSTOR 3594724.

- [7][8][9]

- Lynteris, Christos; Fearnley, Lyle (2 March 2020). "Why shutting down Chinese 'wet markets' could be a terrible mistake". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 2 April 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- Standaert, Michael (15 April 2020). "'Mixed with prejudice': calls for ban on 'wet' markets misguided, experts argue". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- Dalton, Jane (2 April 2020). "Coronavirus: Indian street traders 'risking human health by slaughtering goats, lambs and chickens in squalid conditions'". The Independent. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- [1][11][12][13]

- "Why Wet Markets Are The Perfect Place To Spread Disease". NPR.org. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Standaert, Michael (15 April 2020). "'Mixed with prejudice': calls for ban on 'wet' markets misguided, experts argue". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 April 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- [1][15][11][16]

- Woo, Patrick CY; Lau, Susanna KP; Yuen, Kwok-yung (2006). "Infectious diseases emerging from Chinese wet-markets: zoonotic origins of severe respiratory viral infections". Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 19 (5): 401–407. doi:10.1097/01.qco.0000244043.08264.fc. ISSN 0951-7375. PMC 7141584. PMID 16940861.

- Wan, X.F. (2012). "Lessons from Emergence of A/Goose/Guangdong/1996-Like H5N1 Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Viruses and Recent Influenza Surveillance Efforts in Southern China: Lessons from Gs/Gd/96-like H5N1 HPAIVs". Zoonoses and Public Health. 59: 32–42. doi:10.1111/j.1863-2378.2012.01497.x. PMC 4119829. PMID 22958248.

- Westcott, Ben; Wang, Serenitie (15 April 2020). "China's wet markets are not what some people think they are". CNN. Archived from the original on 15 April 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- [18][19][20]

- "Study on the Way Forward of Live Poultry Trade in Hong Kong" (PDF). Food and Health Bureau. March 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 May 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- Rahman, Khaleda (28 March 2020). "PETA launches petition to shut down live animal markets that breed diseases like COVID-19". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- Reardon, Thomas; Timmer, C. Peter; Minten, Bart (31 July 2012). "Supermarket revolution in Asia and emerging development strategies to include small farmers". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (31): 12332–12337. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10912332R. doi:10.1073/pnas.1003160108. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3412023. PMID 21135250.

- Samuel, Sigal (15 April 2020). "The coronavirus likely came from China's wet markets. They're reopening anyway". Vox. Archived from the original on 16 April 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- [15][16][23][24][25]

- [1][2][3]

- Yu, Verna (16 April 2020). "What is a wet market?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 April 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

While “wet markets”, where water is sloshed on produce to keep it cool and fresh, may be considered unsanitary by western standards, most do not trade in exotic or wild animals and should not be confused with “wildlife markets” – now the focus of vociferous calls for global bans.

- Maron, Dina Fine (15 April 2020). "'Wet markets' likely launched the coronavirus. Here's what you need to know". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 19 April 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- Hui, Mary (16 April 2020). "Wet markets are not wildlife markets, so stop calling for their ban". Quanta Magazine. Archived from the original on 20 April 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- Suen, Thomas; Goh, Brenda (12 April 2020). "Wet markets in China's Wuhan struggle to survive coronavirus blow". Reuters. Archived from the original on 22 April 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

That has prompted heavy scrutiny for wet markets, a key facet of China’s daily life, even though only a few sell wildlife. Some U.S. officials have called for them, and others across Asia, to be closed.

- [28][29][30][31]

- Yu, Sun; Liu, Xinning (23 February 2020). "Coronavirus piles pressure on China's exotic animal trade". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 17 April 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- Greenfield, Patrick (6 April 2020). "Ban wildlife markets to avert pandemics, says UN biodiversity chief". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- Karesh WB, Cook RA, Bennett EL, Newcomb J (July 2005). "Wildlife trade and global disease emergence". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 11 (7): 1000–2. doi:10.3201/eid1107.050194. PMC 3371803. PMID 16022772.

- [15][33][34][35]

- Reed, John (19 March 2020). "The economic case for ending wildlife trade hits home in Vietnam". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- Palmer, James (27 January 2020). "Don't Blame Bat Soup for the Coronavirus". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- Boyle, Louise (15 May 2020). "Wet markets are not the problem – focus on the billion-dollar international trade in wild animals, experts say". The Independent. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- [11][38][39]

- Tan, Alvin (2013). Wet Markets (PDF). Community Heritage Series. Vol. II. Singapore: National Heritage Board. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 February 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "New Singapore English words". Oxford University Press. 2016. Archived from the original on 4 September 2019. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- Burton, Dawn (2008). Cross-Cultural Marketing: Theory, Practice and Relevance. Routledge. p. 146. ISBN 9781134060177.

- Chandran, Rina (7 February 2020). "Traditional markets blamed for virus outbreak are lifeline for Asia's poor". Reuters. Archived from the original on 23 April 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- de Greef, Kimon (17 June 2020). "'People fear what they don't know': the battle over 'wet' markets, a vital part of culinary culture". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- Shaheen, Therese (19 March 2020). "The Chinese Wild-Animal Industry and Wet Markets Must Go". National Review. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- Hu, Dong-wen; Liu, Chen-xing; Zhao, Hong-bo; Ren, Da-xi; Zheng, Xiao-dong; Chen, Wei (2019). "Systematic study of the quality and safety of chilled pork from wet markets, supermarkets, and online markets in China". Journal of Zhejiang University Science B. 20 (1): 95–104. doi:10.1631/jzus.B1800273. ISSN 1673-1581. PMC 6331336. PMID 30614233.

- Zhong, Shuru; Crang, Mike; Zeng, Guojun (2020). "Constructing freshness: the vitality of wet markets in urban China". Agriculture and Human Values. 37 (1): 175–185. doi:10.1007/s10460-019-09987-2. ISSN 0889-048X.

- Roughneen, Simon (8 October 2018). "Southeast Asia's traditional markets hold their own". Nikkei Asian Review. Archived from the original on 14 March 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "Nanmen Market to close for renovation after 38 years". Focus Taiwan. 6 October 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- Agricultural Trade Highlights. Foreign Agricultural Service. 1994. p. 12.

- Bougoure, Ursula; Lee, Bernard (2009). Lindgreen, Adam (ed.). "Service quality in Hong Kong: wet markets vs supermarkets". British Food Journal. 111 (1): 70–79. doi:10.1108/00070700910924245. ISSN 0007-070X.

- Mele, Christopher; Ng, Megan; Chim, May Bo (2015). "Urban markets as a 'corrective' to advanced urbanism: The social space of wet markets in contemporary Singapore". Urban Studies. 52 (1): 103–120. doi:10.1177/0042098014524613. ISSN 0042-0980. S2CID 154733767.

- "Fresh Meat". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 25 November 2014. Archived from the original on 25 October 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "New Coronavirus 'Won't Be the Last' Outbreak to Move from Animal to Human". Goats and Soda. NPR. 5 February 2020. Archived from the original on 3 March 2020. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- "Calls for global ban on wild animal markets amid coronavirus outbreak". The Guardian. London. 24 January 2020. Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- Borzée, Amaël; McNeely, Jeffrey; Magellan, Kit; Miller, Jennifer R.B.; Porter, Lindsay; Dutta, Trishna; Kadinjappalli, Krishnakumar P.; Sharma, Sandeep; Shahabuddin, Ghazala; Aprilinayati, Fikty; Ryan, Gerard E.; Hughes, Alice; Abd Mutalib, Aini Hasanah; Wahab, Ahmad Zafir Abdul; Bista, Damber; Chavanich, Suchana Apple; Chong, Ju Lian; Gale, George A.; Ghaffari, Hanyeh; Ghimirey, Yadav; Jayaraj, Vijaya Kumaran; Khatiwada, Ambika Prasad; Khatiwada, Monsoon; Krishna, Murali; Lwin, Ngwe; Paudel, Prakash Kumar; Sadykova, Chinara; Savini, Tommaso; Shrestha, Bharat Babu; Strine, Colin T.; Sutthacheep, Makamas; Wong, Ee Phin; Yeemin, Thamasak; Zahirudin, Natasha Zulaika; Zhang, Li (2020). "COVID-19 Highlights the Need for More Effective Wildlife Trade Legislation". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. Elsevier BV. 35 (12): 1052–1055. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2020.10.001. ISSN 0169-5347. PMC 7539804. PMID 33097287.

- Fujiyama, Emily Wang; Moritsugu, Ken (11 February 2021). "EXPLAINER: What the WHO coronavirus experts learned in Wuhan". Associated Press. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- Hui, David S.; I Azhar, Esam; Madani, Tariq A.; Ntoumi, Francine; Kock, Richard; Dar, Osman; Ippolito, Giuseppe; Mchugh, Timothy D.; Memish, Ziad A.; Drosten, Christian; Zumla, Alimuddin; Petersen, Eskild (2020). "The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health – The latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. Elsevier BV. 91: 264–266. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.009. ISSN 1201-9712. PMC 7128332. PMID 31953166.

- Huang, Chaolin; Wang, Yeming; Li, Xingwang; Ren, Lili; Zhao, Jianping; Hu, Yi; Zhang, Li; Fan, Guohui; Xu, Jiuyang; Gu, Xiaoying; Cheng, Zhenshun (24 January 2020). "Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China". The Lancet. 395 (10223): 497–506. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7159299. PMID 31986264.

- Keevil, William; Lang, Trudie; Hunter, Paul; Solomon, Tom (24 January 2020). "Expert reaction to first clinical data from initial cases of new coronavirus in China". Science Media Centre. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- Spinney, Laura (28 March 2020). "Is factory farming to blame for coronavirus?". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Archived from the original on 30 March 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

Most of the attention so far has been focused on the interface between humans and the intermediate host, with fingers of blame being pointed at Chinese wet markets and eating habits,...

- "China's Wet Markets, America's Factory Farming". National Review. 9 April 2020. Archived from the original on 9 April 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "Building a factory farmed future, one pandemic at a time". grain.org. Archived from the original on 11 April 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- Rowe, Lizzie. "One welfare and Covid-19". Sustainable Food Trust. Archived from the original on 21 April 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- Fickling, David (3 April 2020). "China Is Reopening Its Wet Markets. That's Good". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 9 April 2020.

- "China Could End the Global Trade in Wildlife". Sierra Club. 26 March 2020. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- "Coronavirus expert calls for shut down of Asia's wildlife markets". Nine News Australia. Archived from the original on 30 March 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- "Wild Animal Markets Spark Fear in Fight Against Coronavirus". Time. Archived from the original on 27 March 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- "Africa Risks Virus Outbreak From Wildlife Trade". WildAid. 28 February 2020. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- "A sea change in China's attitude towards wildlife exploitation may just save the planet". Daily Maverick. 2 March 2020. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

Knights hoped China would also play a role to help “countries around the world. It’s no good simply banning the trade in China. The same risks are very much out there in Asia as well as Africa.”

- "Crackdown on wet markets and illegal wildlife trade could prevent the next pandemic". Mongabay India. 25 March 2020. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

...what we do know is that wet markets such as Wuhan, and for that matter Agartala’s Golbazar or the thousands such that exist in Asia and Africa allow for easy transmission of viruses and other pathogens from animals to humans.

- Mekelburg, Madlin. "Fact-check: Is Chinese culture to blame for the coronavirus?". Austin American-Statesman. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Forgey, Quint (3 April 2020). "'Shut down those things right away': Calls to close 'wet markets' ramp up pressure on China". Politico. Archived from the original on 4 April 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- Greenfield, Patrick (6 April 2020). "Ban wildlife markets to avert pandemics, says UN biodiversity chief". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- Fortier-Bensen, Tony (9 April 2020). "Sen. Lindsey Graham, among others, urge global ban of live wildlife markets and trade". ABC News. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Beech, Peter (18 April 2020). "What we've got wrong about China's 'wet markets' and their link to COVID-19". World Economic Forum. Archived from the original on 18 April 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- Forrest, Adam (13 April 2021). "WHO calls for ban on sale of live animals in food markets to combat pandemics". The Independent. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- Nadimpalli, Maya L; Pickering, Amy J (2020). "A call for global monitoring of WASH in wet markets". The Lancet Planetary Health. 4 (10): e439–e440. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30204-7. ISSN 2542-5196. PMC 7541042. PMID 33038315.

- Petrikova, Ivica; Cole, Jennifer; Farlow, Andrew (2020). "COVID-19, wet markets, and planetary health". The Lancet Planetary Health. 4 (6): e213–e214. doi:10.1016/s2542-5196(20)30122-4. ISSN 2542-5196. PMC 7832206. PMID 32559435.

- Barnett, Tony; Fournié, Guillaume (January 2021). "Zoonoses and wet markets: beyond technical interventions". The Lancet Planetary Health. 5 (1): e2–e3. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30294-1. ISSN 2542-5196. PMC 7789916. PMID 33421407.

- Soon, Jan Mei; Abdul Wahab, Ikarastika Rahayu (1 September 2021). "On-site hygiene and biosecurity assessment: A new tool to assess live bird stalls in wet markets". Food Control. 127: 108108. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2021.108108. ISSN 0956-7135.

- "Wuhan Is Returning to Life. So Are Its Disputed Wet Markets". Bloomberg Australia-NZ. 8 April 2020. Archived from the original on 9 April 2020.

- St. Cavendish, Christopher (11 March 2020). "No, China's fresh food markets did not cause coronavirus". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- Kogan, Nicole E; Bolon, Isabelle; Ray, Nicolas; Alcoba, Gabriel; Fernandez-Marquez, Jose L; Müller, Martin M; Mohanty, Sharada P; Ruiz de Castañeda, Rafael (2019). "Wet Markets and Food Safety: TripAdvisor for Improved Global Digital Surveillance". JMIR Public Health and Surveillance. 5 (2): e11477. doi:10.2196/11477. ISSN 2369-2960. PMC 6462893. PMID 30932867.

- Gómez, Miguel I.; Ricketts, Katie D. (2013). "Food value chain transformations in developing countries: Selected hypotheses on nutritional implications" (PDF). Food Policy. 42: 139–150. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2013.06.010. S2CID 153711764.

- "Improving diets in an era of food market transformation: Challenges and opportunities for engagement between the public and private sectors" (PDF). Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition policy brief. April 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- Weinberger, Katinka; Pasquini, Margaret; Kasambula, Phyllis; Abukutsa-Onyango, Mary (2011). "Supply Chains for Indigenous Vegetables in Urban and Peri-urban Areas of Uganda and Kenya: a Gendered Perspective". In Mithöfer, Dagmar; Waibel, Hermann (eds.). Vegetable Production and Marketing in Africa: Socio-economic Research. Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International. pp. 169–181. ISBN 9781845936495.

- "Strong Growth Persists in Nigeria's Wine Market" (PDF). USDA Foreign Agricultural Service. 1 July 2011. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

More wine and spirits are now sold to the consumers and re-sellers through the wholesalers located in the traditional open wet markets (mostly patronized by the low and middle income consumers).

- Grace, Delia; Dipeolu, Morenike; Alonso, Silvia (2019). "Improving food safety in the informal sector: nine years later". Infection Ecology & Epidemiology. 9 (1): 1579613. doi:10.1080/20008686.2019.1579613. ISSN 2000-8686. PMC 6419621. PMID 30891162.

- Grace, Delia (October 2015). "Food Safety in Developing Countries:An Overview" (PDF). International Livestock Research Institute. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- Oluwole, Josiah (27 June 2018). "Oyo govt begins crackdown on illegal abattoirs in Ibadan". Premium Times. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- "5 dead, station razed as police clash with butchers in Ibadan". Vanguard. 29 June 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- "Making Retail Modernisation in Developing Countries Inclusive". Discussion Paper. 2/2016. German Development Institute. 2016.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Reardon, Thomas; Gulati, Ashok (2008). "The Rise of Supermarkets and Their Development Implications". International Food Policy Research Institute Discussion Paper.

- Reardon, Thomas; Timmer, C. Peter; Barrett, Christopher B.; Berdegué, Julio (2003). "The Rise of Supermarkets in Africa, Asia, and Latin America". American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 85 (5): 1140–1146. doi:10.1111/j.0092-5853.2003.00520.x. ISSN 0002-9092.

- "Colombia Retail Food Sector" (PDF). USDA Foreign Agricultural Service. 6 October 2010. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- Hofverberg, Elin (31 December 2020). "Greenland". Regulation of Wild Animal Wet Markets (PDF) (Report). Library of Congress. pp. 49–53. LL File No. 2020-019215. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- "Resources and industry". Government of Greenland. Archived from the original on 23 February 2012. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- "Sådan undgår du at blive smittet med trikiner!". Naalakkersuisut (in Danish). 12 April 2017. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- "Central de Abasto: bomba de tiempo y nido de delincuencia". El Imparcial (Oaxaca). 9 May 2019. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- Anderson, D.; Kerr, W.A.; Sanchez, G.; Ochoa, R. (2002). "Cattle/beef subsector's structure and competition under free trade". In Loyns, R.M.A.; Meilke, K.; Knutson, R.D.; Yunez-Naude, A. (eds.). Structural changes as a source of trade disputes under NAFTA. Proceedings of the Seventh Agricultural and Food Policy Systems Information Workshop. Winnipeg, Canada: Friesens. pp. 231–258.

- Huerta-Leidenz, Nelson; Ruíz-Flores, Agustín; Maldonado-Siman, Ema; Valdéz, Alejandra; Belk, Keith E. (2014). "Survey of Mexican retail stores for US beef product". Meat Science. 96 (2): 729–736. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2013.10.008. PMID 24200564.

- Srikanth, Anagha (21 April 2020). "America has dozens of live animal 'wet' markets — and Joaquin Phoenix is calling for them to be banned because of coronavirus". The Hill. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- Zhong, Taiyang; Si, Zhenzhong; Crush, Jonathan; Xu, Zhiying; Huang, Xianjin; Scott, Steffanie; Tang, Shuangshuang; Zhang, Xiang (2018). "The Impact of Proximity to Wet Markets and Supermarkets on Household Dietary Diversity in Nanjing City, China". Sustainability. 10 (5): 1465. doi:10.3390/su10051465. ISSN 2071-1050.

- Jia, Shi (31 May 2018). "Regeneration and reinvention of Hangzhou's wet markets". Shanghai Daily. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- [11][16][29][30][31][66]

- Pladson, Kristie (25 March 2021). "Coronavirus: A death sentence for China's live animal markets". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- "COVID-19: What we know so far about the 2019 novel coronavirus". Archived from the original on 5 February 2020.

- Gorman, James (27 February 2020). "China's Ban on Wildlife Trade a Big Step, but Has Loopholes, Conservationists Say". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 13 March 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "The Friend Of China, and Hong Kong Gazette" (PDF). 12 May 1842. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- "EmeraldInsight". EmeraldInsight.com. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- Chong, Sei (18 March 2011). "A Guide to Hong Kong's Wet Markets". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 21 January 2012. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- "Chapter IV – Environmental Hygiene". Annual Report 2018. Food and Environmental Hygiene Department. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- "Report No. 51 of the Director of Audit — Chapter 6" (PDF). Audit Commission. November 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 December 2015. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- "Cap. 132BU Slaughterhouses Regulation". Hong Kong e-Legislation. Department of Justice.

- "Public markets" (PDF). Legislative Council Secretariat. 27 September 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 October 2019. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- Goyal, Malini (9 September 2018). "International food giant Cargill is changing the way it does business". The Economic Times. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

Even the meat market in India is largely a wet market -a market selling fresh meat, fish and other such produce — and has small, unorganised players.

- Ghosal, Sutanuka (4 April 2018). "ICRA predicts decent growth for domestic poultry industry". The Economic Times. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- Mane, B. G. (16 April 2012). "Status and prospects of Indian meat industry". Food & Beverage News. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- Minten, Bart; Reardon, Thomas; Sutradhar, Rajib (2010). "Food Prices and Modern Retail: The Case of Delhi". World Development. 38 (12): 1775–1787. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.585.2560. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2010.04.002.

- "Global Market Snapshot" (PDF). Meat & Livestock Australia. October 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- Amindoni, Ayomi (30 April 2016). "Jokowi wants traditional markets to compete with shopping malls". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- Maulia, Erwida; Damayanti, Ismi (13 July 2020). "Jakarta raises alarm as COVID-19 cases keep rising in Indonesia". Nikkei Asia. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- "Negri hawkers, food trucks to operate 7am-8pm from March 24". The Star. 22 March 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- Pabico, Alecks P. (2002). "Death of the Palengke". Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism. Archived from the original on 23 December 2013. Retrieved 5 January 2009.

- Napallacan, Jhunnex (28 March 2008). "6 Cebu rice retailers suspended for violations". Breaking News / Regions. Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 6 October 2009. Retrieved 7 January 2009.

- Garcia, Bong (21 April 2007). "Food agency intensifies 'Palengke Watch'". Sun.Star Zamboanga. Archived from the original on 12 February 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2009.

- Huang-Teves, Janette (7 September 2018). "Teves: Palengke Boy: The family's digital wet market buddy". Sun.Star. Archived from the original on 8 September 2018. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- Domingo, Katrina (26 March 2020). "Taking cue from Pasig, Valenzuela eyes own market-on-wheels amid quarantine". ABS-CBN Corporation. Archived from the original on 26 March 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "Singapore wet markets: Reminder of bygone days". CNN. 22 June 2015. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- United States. Foreign Agricultural Service. Dairy, Livestock, and Poultry Division, United States. World Agricultural Outlook Board (1992). U.S. Trade and Prospects: Dairy, livestock, and poultry products. The Service. p. 3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kottawatta, Kottawattage; Van Bergen, Marcel; Abeynayake, Preeni; Wagenaar, Jaap; Veldman, Kees; Kalupahana, Ruwani (2017). "Campylobacter in Broiler Chicken and Broiler Meat in Sri Lanka: Influence of Semi-Automated vs. Wet Market Processing on Campylobacter Contamination of Broiler Neck Skin Samples". Foods. 6 (12): 105. doi:10.3390/foods6120105. ISSN 2304-8158. PMC 5742773. PMID 29186018.

- Wei, Clarissa (4 December 2020). "How Taiwan's Largest Wet Market Was Torn Down and Came Back Stronger Than Ever". The News Lens. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- Trappey, Charles V. (1 March 1997). "Are Wet Markets Drying Up?". Taiwan Today. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- de Mooij, Marieke (2003). Consumer Behavior and Culture: Consequences for Global Marketing and Advertising. Chronicle Books. p. 295. ISBN 9780761926689.

- Yen, Bao (12 June 2017). "A Hanoi wet market at the crossroads of modernity". VnExpress. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- Aubry, Christine; Kebir, Leïla (August 2013). "Shortening food supply chains: A means for maintaining agriculture close to urban areas? The case of the French metropolitan area of Paris". Food Policy. 41: 85–93. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2013.04.006.

- Saskia, Seidel; Mareï, Nora; Blanquart, Corinne (2016). "Innovations in e-grocery and Logistics Solutions for Cities". Transportation Research Procedia. 12: 825–835. doi:10.1016/j.trpro.2016.02.035.

- Jlassi, Sarra; Tamayo, Simon; Gaudron, Arthur; de La Fortelle, Arnaud (July 2017). "Simulating impacts of regulatory policies on urban freight: application to the catering setting" (PDF). 2017 6th IEEE International Conference on Advanced Logistics and Transport (ICALT): 106–112. doi:10.1109/ICAdLT.2017.8547005. ISBN 978-1-5386-1623-9. S2CID 54438879.

- Halos, Lénaïg; Thébault, Anne; Aubert, Dominique; Thomas, Myriam; Perret, Catherine; Geers, Régine; Alliot, Annie; Escotte-Binet, Sandie; Ajzenberg, Daniel; Dardé, Marie-Laure; Durand, Benoit; Boireau, Pascal; Villena, Isabelle (February 2010). "An innovative survey underlining the significant level of contamination by Toxoplasma gondii of ovine meat consumed in France". International Journal for Parasitology. 40 (2): 193–200. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.06.009. PMID 19631651.

- Pasquier, Jérémy; Lafont, Anne-Gaëlle; Jeng, Shan-Ru; Morini, Marina; Dirks, Ron; van den Thillart, Guido; Tomkiewicz, Jonna; Tostivint, Hervé; Chang, Ching-Fong; Rousseau, Karine; Dufour, Sylvie (20 November 2012). "Multiple Kisspeptin Receptors in Early Osteichthyans Provide New Insights into the Evolution of This Receptor Family". PLOS ONE. 7 (11): e48931. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...748931P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0048931. PMC 3502363. PMID 23185286.

- Brayne, M. L. (1972). "Rungis: The New Paris Market". Geography. 57 (1): 47–51. ISSN 0016-7487. JSTOR 40567707.

- Gilli, Monica; Ferrari, Sonia (4 March 2018). "Tourism in multi-ethnic districts: the case of Porta Palazzo market in Torino". Leisure Studies. 37 (2): 146–157. doi:10.1080/02614367.2017.1349828. S2CID 149121283.

- Black, Rachel Eden (1 May 2005). "The Porta Palazzo farmers' market: local food, regulations and changing traditions". Anthropology of Food (4). doi:10.4000/aof.157.

- Medina, F. Xavier (31 December 2013). "Porta Palazzo, Anthropology of an Italian Market". Anthropology of Food (S8). doi:10.4000/aof.7429.

- "Dublin City Council to take possession of Iveagh Market". Raidió Teilifís Éireann. 12 January 2018. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Kelly, Olivia (7 January 2015). "Work to begin on €90m redevelopment of Iveagh Markets". Irish Times. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Kelly, Olivia (19 August 2017). "Call for Iveagh Markets to be returned to Dublin City Council". Irish Times. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Corsetti, Stephanie (9 April 2020). "What is a wet market and why are they allowed to continue amid the coronavirus crisis?". Special Broadcasting Service. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- "Calls mount for investigation into 'dangerous' wet markets". Sky News Australia. 23 April 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

What we’re talking about isn’t all wet markets, because the Sydney fish market is a wet market, what we’re talking about here is unregulated markets that engage in some exotic species that are dangerous

- "Coronavirus: Australia wants wet market probe as China faces backlash". Herald Sun. 23 April 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- "How to prevent the next pandemic from wet markets". Daily Mercury. 28 April 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

Australia also has wet markets - e.g. the Melbourne and Sydney Fish Market.

- "Coronavirus: Australia urges G20 action on wildlife wet markets". BBC. 23 April 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

Speaking to the ABC on Thursday, agriculture minister David Littleproud said he was not targeting all food markets. "A wet market, like the Sydney fish market, is perfectly safe," he said.

External links

Media related to Wet markets at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Wet markets at Wikimedia Commons