1977 Atocha massacre

The 1977 Atocha massacre was an attack by right-wing extremists in the center of Madrid on January 24, 1977, which saw the assassination of five labor activists from the Communist Party of Spain (PCE) and the workers' federation Comisiones Obreras (CC.OO). The act occurred within the wider context of far-right reaction to Spain's transition to constitutional democracy following the death of dictator Francisco Franco. Intended to provoke a violent left-wing response that would provide legitimacy for a subsequent right-wing counter coup d'état, the massacre had an immediate opposite effect; generating mass popular revulsion of the far-right and accelerating the legalization of the long-banned Communist Party.

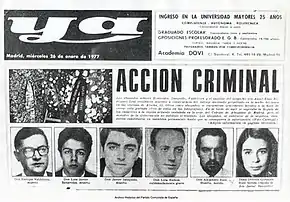

Front page of the January 26, 1977 edition of Ya newspaper depicting the victims | |

| Native name | Matanza de Atocha de 1977 |

|---|---|

| Date | January 24, 1977 |

| Time | 22:30 CET (21:30 UTC) |

| Location | Calle de Atocha 55, Madrid |

| Coordinates | 40°24′35″N 3°41′37″W |

| Casualties | |

| 5 dead | |

| 4 wounded | |

On the evening of January 24, three men entered a legal support office for workers run by the PCE on Atocha Street in central Madrid, and opened fire on all present. Those killed were labor lawyers Enrique Valdelvira Ibáñez, Luis Javier Benavides Orgaz and Francisco Javier Sauquillo; law student Serafín Holgado de Antonio; and administrative assistant Ángel Rodríguez Leal. Severely wounded in the attack were Miguel Sarabia Gil, Alejandro Ruiz-Huerta Carbonell, Luis Ramos Pardo and Dolores González Ruiz.

The perpetrators all had links to neo-fascist organizations in Spain opposed to democracy. Those involved in the massacre and their accomplices were sentenced to a total of 464 years in prison, although these terms were later significantly reduced and a number of the perpetrators escaped custody. Doubts remain as to whether all culpable persons were brought to justice.

The events surrounding the massacre are generally considered a crucial turning point in the consolidation of Spain's return to democracy in the late 1970s. Writing on the 40th anniversary of the massacre, journalist Juancho Dumall noted: "It was a terrorist act that marked the future of the country in a way that the murderers would never have suspected and, instead, was the one desired by the victims." Memorialized annually, across Madrid there are 25 streets and squares dedicated to the victims of the Atocha massacre.

Events at 55 Atocha Street

Three men rang the doorbell of 55 Atocha Street between 10:30 pm and 10:45 pm on January 24, 1977. Their target was Joaquín Navarro, the general secretary of the transport union of CC.OO, who at that time was leading a transport strike in Madrid, had fought corruption within the sector and denounced the state-controlled labor organization Sindicato Vertical.[2][3]

Two of the men, carrying loaded weapons,[note] entered the office, while the third, carrying an unloaded pistol, stayed at the entrance to keep watch. The first to be killed was Rodríguez Leal. The attackers searched the office and found the eight remaining staff. However, not finding Navarro, as he had departed just before, they decided to kill all present. Told to raise their "little hands up high" the eight were lined up against a wall and shot.[2][4]

Two victims, Luis Javier Benavides and Enrique Valdevira, were killed instantly, and two more, Serafín Holgado and Francisco Javier Sauquillo, died shortly after being taken to hospital. The remaining four, Dolores González Ruiz (the wife of Sauquillo), Miguel Sarabia, Alejandro Ruiz-Huerta and Luis Ramos Pardo were gravely injured, but survived. Ruiz was pregnant at the time and lost the child as a result of the attack. Manuela Carmena, who would later become Mayor of Madrid in 2015, had been in the office earlier in the evening but was called away.[5][6]

The same night, unidentified persons attacked an empty office used by the UGT labor union, affiliated with the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE).[7]

Political context and response

Following Franco's death in November 1975, Spain witnessed a period of significant political instability and violence.[9] Ultra right-wing elements of the armed forces and high-ranking officials from the Franco regime, known as the Búnker,[10] were to varying degrees engaged in a strategy of tension[11] designed to reverse Spain's transition to constitutional democracy.[12][13] The open emergence of independent labor unions in 1976, although still illegal, and an explosion in demands for improvements in working conditions and political reform, led to an upsurge in industrial strife across the country. In 1976, 110 million working days were lost to strikes compared to 10.4 million in 1975.[14] This undermined the power bases of former regime officials, their business allies and those from the Francoist labor organization (Sindicato Vertical).[14] January 1977 proved to be particularly turbulent.[15] On January 23, a student, Arturo Ruiz, was murdered by members of the far-right Apostolic Anticommunist Alliance (also known as Triple A) during a demonstration calling for an amnesty for political prisoners. On January 24, at a protest called to highlight Ruiz's death the day before, police fired tear gas canisters, one of which hit and killed a university student, Mariluz Nájera.[16] On the same day, the far-left organization GRAPO kidnapped the President of the Supreme Council of Military Justice, Emilio Villaescusa Quilis.[17]

In the days immediately after the massacre, calls for stop work protests were heeded by upwards of half a million workers across Spain.[18] The strikes were largest in the Basque Country, Asturias, Catalonia and Madrid, with universities and courts across the country shut down in protest.[19] During a news broadcast on state-television on January 26, the announcer declared solidarity with the stoppages on behalf of the station's staff. In Madrid, between 50,000 and 100,000 people watched in silence as the coffins of three of the victims were taken for burial.[19][20]

The PCE was legalized soon after on April 9, 1977;[21] the Party's earlier embrace of Eurocommunism (essentially a rejection of Soviet-style socialism) and a highly visible role in promoting a peaceful response to the massacre allowed the government the necessary political space to lift the ban in place since 1939.[15][22] With the passing of Act 19 covering labor rights on April 1 and the ratification of the ILO Conventions on freedom of association and collective bargaining on April 20, independent unions became legal and the Francoist Sindicato Vertical system was effectively dissolved.[14][23]

Capture, trial, prison and escape

The murderers, believing themselves well protected via political connections, carried on their lives as normal.[24] Lawyer José María Mohedano recalled: “They had the power of a Franco-era labor union that was still alive and working, as well as the support of some police officers and the entire far-right."[25] They were all linked, directly and indirectly, to the far-right extremist parties the Fuerza Nueva (New Force) and Guerrilleros de Cristo Rey (Warriors of Christ the King).[26]

However, on March 15, 1977, José Fernández Cerrá, Carlos García Juliá and Fernando Lerdo de Tejada were arrested as the perpetrators. Francisco Albadalejo Corredera, provincial secretary of the Francoist transport labor union, was also arrested for having ordered the killings. Leocadio Jiménez Caravaca and Simón Ramón Fernández Palacios, veterans of the Blue Division, were arrested for supplying weapons. Gloria Herguedas, Cerrá's girlfriend, was arrested as an accomplice. During the trial the accused made contacts with well-known leaders of the extreme right, including Blas Piñar (founder of Fuerza Nueva) and Mariano Sánchez Covisa (leader of Guerrilleros de Cristo Rey).[2][25][26]

The trial took place in February 1980 and the defendants were sentenced to a total of 464 years in jail. José Fernández Cerrá and Carlos García Juliá, as the main perpetrators, received prison terms of 193 years each. Albadalejo Corredera received 63 years for ordering the attack (he died in prison in 1985). Four years to Leocadio Jiménez Caravaca and one year to Gloria Herguedas Herrando.[5][25]

Pedro Sánchez @sanchezcastejon Spanish: Hace 43 años mató a 5 personas en el atentado de Atocha. Una matanza que no pudo frenar el deseo de libertad de toda una sociedad. Hoy la Democracia y la Justicia vuelven a triunfar. Hoy llega a Madrid uno de sus asesinos, Carlos García Juliá, tras ser extraditado por Brasil.

43 years ago, he killed 5 people in the Atocha attack. A massacre that could not stop an entire society's desire for freedom. Today democracy and justice triumph again. Today one of the assassins, Carlos García Juliá, arrives in Madrid after being extradited from Brazil.

February 7, 2020[27]

Lerdo de Tejada, who stood watch during the massacre, was temporarily released from prison for family leave in 1979, before the trial, following an intervention by Blas Piñar.[26] He then fled to France, Chile and Brazil, never facing justice as the statute of limitations for his crime expired in 1997.[5]

Due to law reforms in the 1980s, the sentences imposed on Fernández Cerrá and García Juliá were reduced to a maximum of 30 years. Fernández Cerrá was released in 1992 after 15 years in jail; since then, he has paid none of the court-ordered financial compensation to the victims' families (approximately €100,000).[5][24]

In 1991, with more than 10 years remaining in his sentence, García Juliá was unusually granted parole and then in 1994 given permission to take up employment in Paraguay.[28] While his parole was rescinded shortly after, he had already absconded.[29] After more than 20 years on the run, García Juliá was rearrested in Brazil in 2018, extradited to Spain in February 2020, and transferred to Soto del Real prison to serve the remainder of his sentence. Spanish Prime Minister, Pedro Sánchez, called the extradition a triumph of "democracy and justice."[30]

One of the survivors, Miguel Ángel Sarabia, commented in 2005: "Although now it may seem a small thing, the 1980 trial of the Atocha murderers – despite the arrogance of the accused ... – it was the first time that the extreme right was sitting on the bench, tried and condemned."[31]

Subsequent revelations

In March 1984 the Italian newspaper Il Messaggero reported that Italian neo-fascists were involved in the massacre, suggesting a "Black International" network.[32] This theory was further supported in October 1990 after revelations from the Italian CESIS (Executive Committee for Intelligence and Security Services) concerning Operation Gladio, a clandestine anti-communist structure created during the Cold War. It was alleged that Carlo Cicuttini had played a role in the Atocha massacre. Cicuttini had fled to Spain in 1972 following a bombing carried out with Vincenzo Vinciguerra in Peteano, Italy, which had killed three police.[33] He was reported to have had connections to Spanish security services and been active in the anti-ETA paramilitary organization GAL.[34] Sentenced in Italy to life in prison in 1987, Spain denied Italian requests for his extradition. Cicuttini was arrested in France in 1998 and extradited to Italy, where he died in 2010.[35]

While the Atocha murders were the most infamous act during Spain's democratic transition, between 1977 and 1980, far right organizations carried out more than 70 assassinations.[9] Jaime Sartorius, a lawyer who worked on the prosecution at the original trial in 1980, would declare in 2002: "The masterminds are missing. They did not let us investigate. To us, the investigations pointed to the secret services, but only pointed."[5]

Legacy

No one raised their voices, there were no screams or calls for revenge, but only silence. The dignified silence with which my compañeros were farewelled finally broke the loop of violence in this country

– Alejandro Ruiz-Huerta, 2017[36]

On January 11, 2002, the Council of Ministers granted the Grand Cross of the Order of St. Raymond of Peñafort to the four murdered lawyers, with the Cross of the Order given to Ángel Rodríguez Leal.[37][38] Across Madrid, there are 25 streets and squares dedicated to the victims of the Atocha massacre and many more across Spain.[16]

The labor federation CCOO created a foundation to promote the memory of the victims and to advocate for labor and human rights. The Atocha Lawyers Awards were instituted as an annual ceremony in 2002 to coincide with the 25th anniversary of the massacre.[39]

Journalist Juancho Dumall, writing in 2017 on the 40th anniversary of the massacre, highlighted that the attack had the opposite effect of what was intended: "It was a terrorist act that marked the future of the country in a way that the murderers would never have suspected and, instead, was the one desired by the victims."[20] The mass peaceful responses and the subsequent liberalizations (legalization of the PCE, worker and union freedoms) are generally credited as allowing the June 1977 elections, Spain's first in 40 years, to occur peacefully.[25]

Although many celebrate the success of Spain's transition to democracy, debates over the human cost – especially the Pact of Forgetting (Pacto del olvido) – have grown.[40] That debate was echoed in the words of Atocha massacre survivor Dolores González Ruiz, who died in 2015: "In the course of my life, my dreams broke me."[4][41]

Popular culture

The 1979 film Seven Days in January presented an account of the events of the 1977 Atocha massacre. The film won the Golden Prize at 11th Moscow International Film Festival.[42]

Gallery

Memorial designed by Spanish artist Juan Genovés, Plaza de Antón Martín, Madrid

Memorial designed by Spanish artist Juan Genovés, Plaza de Antón Martín, Madrid.jpg.webp) Dedication on the memorial, headed by a quote from Paul Éluard: "If the echo of their voice weakens, we will perish"

Dedication on the memorial, headed by a quote from Paul Éluard: "If the echo of their voice weakens, we will perish"

See also

- List of right-wing terrorist attacks

- List of massacres in Spain

- Spanish transition to democracy

- Seven days in January, 1979 film by Juan Antonio Bardem depicting the Atocha massacre

References

Notes

Footnotes

- Torres, Juan José del Águila. "Dolores González Ruiz". Real Academia de la Historia. Archived from the original on March 20, 2020. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- "25 Años de la 'matanza de Atocha', el crimen que marcó la transición democrática" [25 years since the 'Atocha massacre', the crime that marked the democratic transition]. Terra (in Spanish). January 24, 2002. Archived from the original on January 29, 2010. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- "Selon la police Madrilène: Un règlement de comptes au sein d'un syndicat serait à l'origine du massacre de la rue Atocha" [According to the Madrid police: A trade union settling of accounts is at the heart of the Atocha Street massacre]. Le Monde (in French). March 16, 1977. Archived from the original on May 1, 2020. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- Fraguas, Rafael (April 11, 2015). "Lola González Ruiz: "Me desbarataron mis sueños"" [Lola González Ruiz: My dreams were ruined]. El País (in Spanish). ISSN 1134-6582. Archived from the original on December 27, 2019. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

- Malvar, Aníbal (January 20, 2002). "¿Qué fue de los asesinos de Atocha?" [What became of the Atocha massacre assassins?]. El Mundo (in Spanish). Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- Sanz, Enrique Delgado (March 30, 2015). "Manuela Carmena, la abogada de Atocha que mira a Cibeles" [Manuela Carmena, the Atocha massacre lawyer looks to Cibeles]. La Vanguardia (in Spanish). Archived from the original on January 26, 2020. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- "Tras el salvaje atentado al despacho laboralista de Madrid" [After the brutal attack on the Madrid labor office]. La Vanguardia (in Spanish). January 26, 1977. Archived from the original on February 2, 2019. Retrieved November 26, 2018.

- Fort, José (January 20, 2017). "Dans le massacre d'Atocha, on trouve l'ADN de la démocratie espagnole" [In the Atocha massacre, we find the DNA of Spanish democracy]. L'Humanité (in French). Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- Encarnación, Omar G. (2008). Spanish Politics: Democracy After Dictatorship. Polity. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-7456-3992-5.

- Smith, Angel (2009). "Búnker". Historical Dictionary of Spain. Scarecrow Press. pp. 114–115. ISBN 978-0-8108-6267-8.

- Christie, Stuart (March 24, 2009). "Luís Andrés Edo: Anarchist who fought the repressions of Franco's Spain". The Independent. Archived from the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- Hottinger, Arnold (1976). "Spain One Year after Franco". The World Today. 32 (12): 447. ISSN 0043-9134. JSTOR 40394898.

- Alonso, Alejandro Muñoz (1986). "Golpismo y terrorismo en la transición democrática española" [Coup mentality and terrorism in the Spanish democratic transition]. Reis (in Spanish) (36): 31. doi:10.2307/40183244. JSTOR 40183244.

- Fina, Lluis; Hawkesworth, Richard I. (January 1984). "Trade unions and collective bargaining in post-Franco Spain" (PDF). Labour and Society. International Institute For Labour Studies: International Labour Organisation. 9 (1): 9–14. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 1, 2020.

- González, Fernando Nistal (2013). "El PCE: de la clandestinidad a la legalidad" [The PCE: from secrecy to legality]. Cuadernos de Pensamiento Político (in Spanish) (40): 185. ISSN 1696-8441. JSTOR 23511966.

- "Los abogados laboralistas del despacho de la calle Atocha, historia viva" [The labor lawyers of the Atocha Street office, history alive]. Atocha Lawyers Foundation (in Spanish). Archived from the original on September 15, 2019. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- "Los GRAPO, terroristas germinados en los años 60 – españa" [GRAPO – terrorists born in 1960s Spain]. El Mundo (in Spanish). May 31, 2005. Archived from the original on April 21, 2020. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- Pérez, Jesús María (2002). "25 años desde la Matanza de Atocha: 1977–2002" [25 years since the Atocha massacre: 1977–2002]. Nuevo Claridad. Archived from the original on February 7, 2012. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- Markham, James M. (January 27, 1977). "Madrid, Faced By Strife, Bans Demonstrations". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 20, 2018. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- Dumall, Juancho (January 22, 2017). "La matanza de Atocha, el sangriento minuto cero de la democracia" [The Atocha massacre, the bloody minute zero of democracy]. El Periódico (in Spanish). Archived from the original on May 3, 2020. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

- Marco, Jorge; Anderson, Peter (2016). "Legitimacy by Proxy: Searching for a Usable Past through the International Brigades in Spain's Post-Franco Democracy, 1975–2015" (PDF). Journal of Modern European History. 14 (3): 393. doi:10.17104/1611-8944-2016-3-391. ISSN 1611-8944. JSTOR 26266251. S2CID 147867302.

- Acoca, Miguel (April 10, 1977). "Spain Ends Ban On Communists After 38 Years". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on May 2, 2020. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

- Olea, Manuel Alonso; Rodríguez-Sañudo, Fermín; Guerrero, Fernando Elorza (2018). Labour Law in Spain. Kluwer Law International B.V. paragraphs: 51, 52, 536. ISBN 978-94-035-0184-0.

- Iglesias, Leyre (December 16, 2018). "La última amenaza del único pistolero de la matanza de Atocha que sí cumplió condena" [The last threat of the only Atocha massacre gunman who served time]. El Mundo (in Spanish). Archived from the original on March 25, 2020. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- Altares, Guillermo (February 5, 2016). "The night Spain's transition to democracy nearly derailed". El País. Archived from the original on April 20, 2020. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- Alarcón, Julio Martín (January 22, 2017). "Matanza en Atocha: la sombra de la ultraderecha 40 años después" [Atocha Massacre: the extreme right shadow 40 years later]. El Independiente (in Spanish). Archived from the original on May 26, 2019. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- Pedro Sánchez [@sanchezcastejon] (February 7, 2020). "Hace 43 años mató a 5 personas en el atentado de Atocha. Una matanza que no pudo frenar el deseo de libertad de toda una sociedad. Hoy la Democracia y la Justicia vuelven a triunfar. Hoy llega a Madrid uno de sus asesinos, Carlos García Juliá, tras ser extraditado por Brasil" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- Duva, Jesús; Gayo, Alberto (August 19, 2019). "El asesino de Atocha que estuvo huido 25 años" [The Atocha assassin on the run for 25 years]. El País (in Spanish). ISSN 1134-6582. Archived from the original on November 30, 2019. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- Gortázar, Naiara Galarraga (February 7, 2020). "Carlos García Juliá, coautor de la matanza de Atocha, ingresa en la cárcel de Soto del Real tras ser extraditado" [Carlos García Juliá, coauthor of the Atocha massacre, enters Soto del Real prison after being extradited]. El Pais (in Spanish). Archived from the original on March 12, 2020. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

- Gual, Joan Royo (February 7, 2020). "Carlos García Juliá, ya en prisión, para cumplir la pena pendiente por la matanza de Atocha" [Carlos García Juliá, already in prison, to serve remaining sentence for the Atocha massacre]. El Mundo (in Spanish). Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- Fraguas, Rafael (January 25, 2005). "Memoria viva de las víctimas de la matanza de Atocha" [Living memory of the Atocha massacre victims]. El País (in Spanish). ISSN 1134-6582. Archived from the original on September 12, 2019. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- Arias, Juan (March 24, 1984). "Un neofascista italiano disparó contra los abogados de la calle de Atocha, según un arrepentido" [An Italian neo-fascist shot at the Atocha Street lawyers, according to a repentant criminal]. El País (in Spanish). ISSN 1134-6582. Archived from the original on April 24, 2020. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- González, Miguel (December 2, 1990). "Un informe oficial italiano implica en el crimen de Atocha al 'ultra' Cicuttini, relacionado con Gladio" [An official Italian report implicates the 'ultra' Cicuttini, part of Gladio, in the Atocha crime]. El País (in Spanish). ISSN 1134-6582. Archived from the original on December 10, 2019. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- AFP (April 17, 1998). "Detenido un ultraderechista italiano que vivía en España" [Detention of ultra-right Italian who live in Spain]. El País (in Spanish). ISSN 1134-6582. Archived from the original on September 4, 2019. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

- "Morta l'ex "primula nera"" [Death of the former "black primrose"]. www.ilfriuli.it (in Italian). February 24, 2010. Archived from the original on August 15, 2020. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- Fernández, Juan (January 22, 2017). "Alejandro Ruiz-Huerta, el último testigo" [Alejandro Ruiz-Huerta, the last witness]. El Periódico (in Spanish). Archived from the original on May 3, 2020. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

- "Bulletin of State (p.1578)" (PDF). Agencia Estatal – Boletín Oficial del Estado. January 12, 2002. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- "Bulletin of State (p.1579)" (PDF). Agencia Estatal – Boletín Oficial del Estado. January 12, 2002. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- "Fundación Abogados de Atocha". Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- Buck, Tobias (December 8, 2014). "Spain's lauded transition to democracy under fire". Financial Times. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- McDermott, Annie (February 21, 2020). "Ghosts of the Revolution: A Finales de Enero by Javier Padilla review". Times Literary Supplement. Archived from the original on May 8, 2020. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- "11th Moscow International Film Festival (1979)". MIFF. Archived from the original on April 3, 2014. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

External links

- Atocha Lawyers Foundation (in Spanish)

- Photo essay related to the events surrounding the Atocha massacre El País (January 23, 2017)