AFL–NFL merger

The AFL–NFL merger was the merger of the two major professional American football leagues in the United States at the time: the National Football League (NFL) and the American Football League (AFL).[1] It paved the way for the combined league, which retained the "National Football League" name and logo, to become the most popular sports league in the United States. The merger was announced on the evening of June 8, 1966.[2][3][4] Under the merger agreement, the leagues maintained separate regular-season schedules for the next four seasons—from 1966 through 1969—and then officially merged before the 1970 season to form one league with two conferences.

Background

Early rivals

Following its inception in 1920, the NFL fended off several rival leagues. Before 1960, its most important rival was the All-America Football Conference (AAFC), which began play in 1946. The AAFC differed from the NFL in several ways. Despite relatively strong backing at the league's inception, it ultimately proved an unsustainable venture. The AAFC's most serious weakness resulted from its refusal to implement an initial draft; this caused a massive lack of competitive balance, and resulted in the league's strongest team (the Cleveland Browns) dominating the league and becoming perennial champions.

Due to the AAFC's poor financial situation, the league disbanded after the 1949 season. Three AAFC teams—the Cleveland Browns, the San Francisco 49ers, and the original version of the Baltimore Colts—were absorbed into the NFL in 1950. The league was briefly known as the National-American Football League during the offseason, but reverted to the traditional name of "National Football League" by the time the 1950 season began. The Browns went on to shock NFL loyalists by dominating the older league and winning the championship in their first NFL season, thus proving themselves to be among the best professional football teams of that time.

The 1950s

After the NFL absorbed the AAFC, it had no other rival US leagues throughout the 1950s. The only other professional gridiron football leagues then in operation were in Canada (the leagues that would merge to form the present-day Canadian Football League in 1958). The Interprovincial Rugby Football Union (forerunner of the CFL's East Division) received some attention from US football fans after it secured a broadcasting contract with NBC (the AFL's future television partners).

During the 1950s the Eastern Canadian season started at around the same time as the NFL's; Canadian teams at this time typically played two games per week so as to finish the season before the harsh Canadian winter set in. This arrangement allowed for NFL teams to travel north of the border for preseason contests with the CFL's Eastern clubs. NFL teams won most of these contests, often by large scorelines. The other major Canadian league, the Western Interprovincial Football Union (forerunner of the CFL's West Division) was mostly ignored by the NFL, partly because its teams were regarded as inferior to those in Eastern Canada, but mainly because rail travel to Western Canada was infeasible for a preseason game (air travel remained uncommon). As a result, the Western Conference was already moving toward an earlier start to its season.

All of the professional leagues, including the NFL, derived most of their revenue from ticket sales. Although the NFL dominated the game financially, their advantage was modest by modern standards. The Canadian league enforced strict limits on the number of American players on their rosters, while the popularity of ice hockey in Canada limited the number of talented Canadian athletes that chose to play football. Therefore, NFL teams could retain their dominance on the field without needing to substantially out-spend the Canadian teams. In the absence of a players' labor union (the National Football League Players Association was founded in 1956 but was initially ineffective) or a competing US league, there was little pressure to pay players high salaries. NFL team owners spent as little as possible on players, to maximize their profit.

Emergence of the AFL

In 1959, Lamar Hunt, son of Texas oil magnate H. L. Hunt, attempted to either gain ownership of the Chicago Cardinals with Bud Adams and move them to Dallas,[5] or own an NFL expansion franchise in Dallas.[6] In 1959, the NFL had only two teams that were south of Washington, D.C. and west of Chicago: the San Francisco 49ers and the Los Angeles Rams, both in California. The league, however, was not interested in expansion at the time. Rebuffed in his attempts to gain at least part-ownership in an NFL team, Hunt conceived the idea of a rival professional football league, the American Football League.[7][8] In September 1959, Hunt was approached by the NFL about an expansion team in Dallas, but by then Hunt was only interested in the AFL.[9]

The new league had six franchises by August 1959[10] and eight by the time of its first opening day in 1960: Boston (Patriots), Buffalo (Bills), New York City (Titans), Houston (Oilers), Denver (Broncos), Dallas (Texans), Oakland (Raiders), and Los Angeles (Chargers). While the Los Angeles, New York, Oakland, and Dallas teams shared media markets with NFL teams (the Rams, Giants, 49ers, and the expansion Dallas Cowboys, respectively), the other four teams (Boston, Buffalo, Denver, and Houston) widened the nation's exposure to professional football by serving markets that had no NFL team. In the following years, this additional exposure was widened via the relocation of two of the original eight franchises (the Chargers to San Diego in 1961 and the Texans to Kansas City in 1963), and the addition of two expansion franchises (the Miami Dolphins and Cincinnati Bengals).

From small colleges and predominantly black colleges (a source mainly ignored by the NFL), the AFL signed stars such as Elbert Dubenion (Bluffton), Lionel Taylor (New Mexico Highlands), Tom Sestak (McNeese State), Charlie Tolar and Charlie Hennigan (Northwestern State of Louisiana), Abner Haynes (North Texas State), and a host of others. From major colleges, it signed talented players like LSU's Heisman Trophy winner Billy Cannon, Arkansas's Lance Alworth, Notre Dame's Daryle Lamonica, Kansas' John Hadl, Alabama's Joe Namath, and many more. The AFL also signed players the NFL had given up on: so-called "NFL rejects" who turned out to be superstars that the NFL had mis-evaluated. These included Jack Kemp, Babe Parilli, George Blanda, Ron McDole, Art Powell, John Tracey, Don Maynard, and Len Dawson. In 1960, the AFL's first year, its teams signed half of the NFL's first-round draft choices.

The AFL introduced many policies and rules to professional football which the NFL later adopted, including:

- A 14-game regular season schedule, which the NFL adopted in 1961 (increased from 12 games), exactly one year after the AFL's inaugural season. The CFL's Eastern and Western Conferences had already been playing 14 and 16 game schedules, respectively, for several years. The AAFC in the 1940s also played a 14-game schedule.

- Players' last names on the jersey back (adopted by the NFL in 1970).

- A flashier, exciting style of play, as opposed to conservative-style NFL game plans.

- The introduction of the two-point conversion to pro football, conforming to the college rule adopted in the 1958 NCAA University Division football season.

- This AFL rule was dropped after its last season in 1969. It was later adopted by the NFL in 1994.

- Official time on the scoreboard clock, as opposed to it being kept by on-field officials.

- One network television broadcast package for league games, first with ABC from 1960[14] through 1964, then with NBC.[15]

- The sharing of gate and television revenues by home and visiting teams.

Competition between the two leagues

At first, the NFL ignored the AFL and its eight teams, assuming the AFL would consist of players who could not earn a contract in the NFL, and that fans of professional football would not waste their time watching them when they could watch the NFL. The NFL also had the media advantage: for example, in the 1960s, Sports Illustrated's lead football writer was Tex Maule,[5] who previously worked with NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle when Rozelle was the general manager of the L.A. Rams and Maule was the team's public relations director; Maule "was certainly an NFL loyalist",[16] and several sports reporters took his deprecatory columns about the AFL as fact. Another example was Dallas Cowboys general manager Tex Schramm, a close friend of Rozelle (Schramm hired Rozelle as Rams' GM), who was influential in NFL coverage by its national TV partner, CBS, including the network's employment of former NFL players as game announcers and the absence of AFL scores and reports on the network.

Nevertheless, the AFL enjoyed one critical advantage over its established rival, which was that its owners on average were wealthier than their NFL counterparts. With a few notable exceptions such as the notorious Harry Wismer in New York, Hunt had successfully recruited owners who not only had deep pockets, but more importantly, unlike earlier leagues, most AFL owners had the patience and willingness to absorb the inevitable financial losses of the fledgling league's early years. Therefore, in spite of the bad press, and unlike the NFL's previous rivals, the AFL was able to survive and grow, and began to prosper in the mid-1960s after the relocation of the Chargers and Texans to non-NFL markets, the sale and rebranding of the New York Titans (to the Jets), and the Jets' signing of University of Alabama quarterback Joe Namath to an unprecedented $427,000 contract. The league's financial survival was further buoyed by NBC's $36 million, five-year contract to televise AFL games beginning in 1965.[15]

As the rivalry between the leagues intensified, both leagues entered into a massive bidding war over the top college prospects, paying huge amounts of money to unproven rookies in order to outbid each other for the best players coming out of college. The bidding wars escalated in the mid-1960s, with the respective drafts held on the same day in the late fall. Because of the intense competition, teams often drafted players that they thought had a good chance of signing, instead of selecting the best available players. For example, 1965 Heisman Trophy winner Mike Garrett, a running back from USC in Los Angeles, was expected to sign with an NFL team, so he was not taken in the 1966 AFL draft until the 20th (final) round by the Kansas City Chiefs. In the 1966 NFL Draft, he was taken by the Los Angeles Rams with the 18th overall selection. Garrett surprisingly shunned the NFL and signed with Kansas City; he helped lead them to the AFL title as a rookie. The previous year, the Chiefs used their first round pick on Gale Sayers, who signed with the NFL's Chicago Bears.

By contrast, many NFL owners had comparatively little wealth outside the value of their respective franchises. The NFL consistently outdrew the AFL at the gate, especially in the AFL's first few seasons, thus ensuring that the older league's franchises remained considerably more lucrative enterprises compared to their AFL rivals. Nevertheless, NFL owners knew they did not have unlimited resources to wage a protracted bidding war with the AFL. Moreover, owners in both leagues feared that the reserve clause written into the standard players' contracts of both leagues would not survive a legal challenge. These fears proved well-founded since after the merger the upstart World Hockey Association (which unlike the AFL chose to challenge the reserve clause enforced by its established rival) ultimately prevailed in court.

National Football League teams had long adhered to the practice of drafting for and retaining the NFL rights to players who signed with the CFL and other leagues. This policy ensured, for example, that if a Canadian Football League player developed into a star, only one particular NFL team would have the right to try and sign him. This ensured that NFL teams did not become embroiled among themselves in costly bidding wars for top free agents. Once the American Football League commenced operations, NFL teams extended this policy to cover AFL players as well, and the AFL promptly reciprocated the arrangement. This arrangement soon evolved into a gentlemen's agreement between the two U.S. leagues — once a player signed with a team, be it from the AFL or NFL, teams in both leagues were expected to honor each other's player contracts in their entirety (including the respective reserve clauses) and not sign players who were under contract with a team in the rival league.

This unwritten agreement was broken in May 1966 when the NFL's New York Giants signed Pete Gogolak, the first professional soccer-style placekicker, who had played out his option in 1965 with the AFL's Buffalo Bills.[17][18][19] The NFL's breach of trust resulted in retaliation by the AFL: Oakland Raiders co-owner Al Davis took over as AFL Commissioner in April 1966, and he stepped up the bidding war after the Gogolak transfer, signing notable NFL players, including John Brodie[20] Mike Ditka,[18] and Roman Gabriel[21] to contracts with AFL teams, but after the merger agreement in June, they wound up staying in the older league. Both leagues spent a combined $7 million signing their 1966 draft picks.

The merger agreement

Contrary to common belief, it was not the AFL, but the NFL that initiated discussions for a merger between the two leagues, as it was fearful that Davis' "take no prisoners" tactics would seriously diminish the older league's profitability and/or drastically reduce its talent base. Tex Schramm, the general manager of the NFL's Dallas Cowboys since 1960, secretly contacted AFL owners, led by Lamar Hunt of Kansas City, and asked if they were interested in a merger.[4] The talks were conducted without the knowledge of Davis, the new AFL commissioner.[20] On the evening of June 8, 1966, the collaborators announced a merger agreement in New York.[2][3][4][22] Under the agreement:

- The two leagues would combine to form an expanded league with 24 teams, to be increased to 26 teams by 1969, and to 28 by 1970, or soon thereafter. The expansion commitment was included primarily to mollify Congressional opposition (especially from locales which still lacked professional football) which the owners knew would follow any proposed merger. The teams eventually added were the New Orleans Saints in 1967, the Cincinnati Bengals in 1968, and the Seattle Seahawks and Tampa Bay Buccaneers in 1976 (the Seahawks and Buccaneers were added after the completion of the merger). The Atlanta Falcons and the Miami Dolphins were already established and set to start play for the 1966 season, before the merger was announced in June.

- All existing franchises would be retained, and none of them would be moved outside of their metropolitan areas. The agreement also stipulated that no new franchises were to be placed by either league within the media markets of the other. Among other things, this particular clause of the agreement effectively ended the city of Milwaukee's pursuit of an expansion AFL team following an unsuccessful effort to lure the Green Bay Packers to Milwaukee full-time.[23]

- AFL "indemnities" would be paid to NFL teams which shared markets with AFL teams. Specifically, the New York Giants would receive payments from the New York Jets, and the San Francisco 49ers would get money from the Oakland Raiders. The shared-markets issue was part of earlier, informal merger talks (held as early as 1964), talks the AFL rejected when the NFL wanted the Jets and Raiders relocated (to Memphis and Portland, respectively).

- Both leagues would hold a "Common Draft" of college players, effectively ending the bidding war between the two leagues over the top college prospects. (The first such draft occurred in mid-March 1967.)

- The leagues would maintain separate regular season schedules through 1969 (though some preseason games during that time featured AFL-vs-NFL matchups). The leagues also agreed to play an annual AFL-NFL World Championship Game,[24] matching the championship teams of each league, beginning in January 1967; the game that would eventually become known as the Super Bowl.

- The two leagues would officially merge in 1970 to form one league with two conferences. The merged league would be known as the National Football League. The history and records of the AFL would be incorporated into the older league. While the AFL name and logo were to be officially retired, the AFC's pre-2009 logos were largely based on the old AFL logo.

- The AFL would abolish the office of AFL Commissioner immediately and recognize the NFL Commissioner as the overall chief executive of professional football. This arrangement, which was in keeping with a provision of the NFL's Constitution dating from 1941 (when the title of Commissioner was introduced in football) that sought to invest the NFL's chief executive with a similar level of authority to that exercised by the Commissioner of Baseball, formally ended the AFL's six-year run as an independent league. However, the AFL was permitted to retain rule differences such as the two point conversion for the remainder of its existence - one of the reasons the full merger was delayed until after the 1969 season was that this coincided with the expiration of the AFL's contract with Spalding.

- NFL Films would start recording game footage for the AFL starting in 1968 under a newly established "AFL Films" division, which was simply the regular NFL Films crew wearing separate jackets to appease AFL loyalists.[25]

Following the agreement, American Football League owners created the office of AFL President with a mandate to administer the league's day-to-day business in a semi-autonomous manner, much like the way the constituent leagues of Major League Baseball operated at the time. The owners had hoped Davis would continue to serve in that role, but Davis (already furious with the owners of both leagues for negotiating a merger without consulting him) flatly refused to consider serving as a subordinate to Pete Rozelle. After Davis resigned as AFL Commissioner on July 25, 1966, Milt Woodard (who was assistant commissioner under the original commissioner Joe Foss and Davis)[26] was appointed to serve as President of the AFL.[27]

Although Pete Rozelle had not initiated the merger negotiations, he quickly endorsed the agreement and remained in his post as NFL Commissioner. Although he was not formally invested with any new title(s), Rozelle was often referred to as the football commissioner or commissioner of football in the media during the four years following the merger agreement. The pre-existing office of NFL President continued effectively unchanged following the agreement. Then occupied by Cleveland Browns owner Art Modell, the NFL presidency was (both before and after the merger agreement) essentially an honorary title that operated in a manner similar to the way in which the league presidencies of MLB operate in the 21st century.

Implementation of the merger depended on the passage of a law by the 89th U.S. Congress, exempting the merged league from antitrust law sanctions. When NFL Commissioner Rozelle and other professional football executives appeared before the Congress' Subcommittee on Antitrust, chaired by New York Representative Emanuel Celler, three points were repeatedly made:

- Rozelle promised that if the merger was allowed, no existing professional football franchise of either league would be moved from any city as a result.

- The combined league would eventually expand to 28 teams as stipulated in the merger agreement.

- Stadiums seating less than 50,000 were declared to be inadequate for professional football's needs, thus compelling teams in stadiums with capacities under that number to expand their current stadiums (most notably the expansion of the Denver Broncos' Mile High Stadium in 1968) or move to newer, larger homes—most notably the Chicago Bears' move from Wrigley Field to Soldier Field in 1971, and the opening of new stadiums for the New England Patriots (Schaefer Stadium in 1971), Kansas City Chiefs (Arrowhead Stadium in 1972), and Buffalo Bills (Rich Stadium in 1973). (The Minnesota Vikings stayed at Metropolitan Stadium, the only sub-50,000 capacity stadium after the merger, until the Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome opened in 1982.) It was this stadium issue that prevented Seattle and Tampa Bay from receiving their expansion teams until 1976; both cities were recruiting the Bills and Patriots to relocate to their cities (in defiance of Rozelle's promise) should they not be able to build a compliant stadium in their home market, and only after those stadiums were built and relocation of existing teams ruled out that the league could issue expansion teams to Seattle and Tampa Bay. Since the 1970s, the league has only played occasionally in sub-50,000 seat stadiums. Exceptions include the 1998 NFL season when the Tennessee Oilers played one season at 40,550 seat Vanderbilt Stadium and also from 2017 through 2019 when the Chargers returned to Los Angeles and temporarily moved into the 27,000 seat Dignity Health Sports Park (known as StubHub Center before 2019) until SoFi Stadium opened in 2020.

In October, Congress passed the new law to permit the merger to proceed.[28] The terms of the merger called for the NFL and AFL to add one team each prior to the 1970 season. Louisiana Representative Hale Boggs and Senator Russell Long were instrumental in passage of the new law, and in return, Rozelle approved creation of the expansion New Orleans Saints franchise less than one month after the bill was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson.

The tenth and final AFL franchise was awarded to former Cleveland Browns owner and coach Paul Brown downstate in Cincinnati. Brown had been seeking a way back into the NFL after being forced out of the Browns organization by Modell. Brown had not been a supporter of the AFL prior to the merger announcement, but quickly realized the AFL was probably his only viable path back into NFL after the older league awarded its sixteenth franchise to New Orleans. Also, Cincinnati was not going to have a 50,000-seat stadium ready (Riverfront Stadium) until 1970. Brown paid $10 million for his franchise (400 times the 1960 franchise fee of $25,000), famously stating "I didn't pay ten million dollars to be in the AFL."[29]

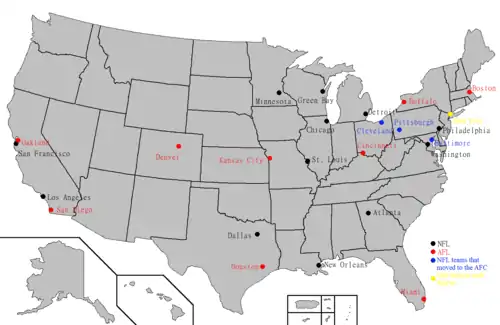

As 1970 approached, three NFL teams (the Baltimore Colts, Cleveland Browns, and Pittsburgh Steelers),[30] agreed to join the ten AFL teams (the Cincinnati Bengals and Miami Dolphins had joined the original Boston Patriots, Buffalo Bills, Denver Broncos, Houston Oilers, Kansas City Chiefs, New York Jets, Oakland Raiders, and San Diego Chargers) to form the American Football Conference (AFC). The other thirteen NFL teams (Atlanta Falcons, Chicago Bears, Dallas Cowboys, Detroit Lions, Green Bay Packers, Los Angeles Rams, Minnesota Vikings, New Orleans Saints, New York Giants, Philadelphia Eagles, St. Louis Cardinals, San Francisco 49ers and Washington Redskins) became part of the National Football Conference (NFC).

Since 1970, the Super Bowl has featured the champions of the AFC and NFC. Both are determined each season by the league's playoff tournament. With the creation of the new conferences of equal size, it was deemed necessary that they each be aligned into three divisions of four or five teams each. Prior to 1970, both leagues experimented with new playoff formats in place of the traditional format where the division champions faced each other in a single championship game, and where one-game playoffs were played to settle ties for the division crown. With the addition of a sixteenth team in 1967 the NFL expanded to four divisions, and also replaced the possibility of tiebreaker games with an elaborate set of performance-based tiebreakers to determine division champions. The AFL waited until its last season to eliminate the possibility of tiebreaker games when it granted the division runners up playoff berths and implemented the NFL tiebreaking formula.

Both playoff formats proved controversial. The 1967 Baltimore Colts tied the Los Angeles Rams for the best record in the NFL at 11-1-2, but because they lost the tiebreaker to the Rams they missed the playoffs altogether as opposed to playing a tiebreaker game as would have occurred in the previous season. In the AFL's final year, the 1969 Houston Oilers claimed a playoff berth despite a mediocre 6-6-2 record - no .500 team had ever qualified for the playoffs in a professional American football league before. To minimize the chance of any recurrence of such controversies, the 1970 playoff format combined elements of both leagues' formats. Four teams would qualify for the postseason from each conference (same as in 1969), thus only the "Best Second Place Team" (as it was originally called) would reach the postseason. Fans and media quickly dubbed this team the "wild card" and the NFL soon made that name official. The playoff format has changed several times since 1970 particularly as additional wild card teams and divisions have been added, but it has always been identical in each conference.

Although the AFC teams quickly decided on a divisional alignment along mostly geographic lines, the 13 NFC owners had trouble deciding which teams would play in which divisions. Many NFC teams were attempting to avoid placement in a division with the Cowboys and/or the Vikings, and were trying to angle their way into the same division as the Saints, the weakest team in professional football at the time. The 49ers and Rams, both in California, were guaranteed to be in the same division as the only NFC teams west of the Rocky Mountains. One early proposal would have put the two California teams together with the three Northeast teams—the New York Giants, Philadelphia Eagles and Washington Redskins—reminiscent of the Western Conference's Coastal Division which had put L.A. and S.F. together with Baltimore and Atlanta from 1967 to 1969. The final five proposals were as follows:

PLAN 1: East: NYG, PHI, WAS, ATL, MIN; Central: CHI, GB, DET, NO; West: LA, SF, DAL, STL.

PLAN 2: East: NYG, PHI, WAS, MIN; Central: ATL, DAL, NO, STL; West: LA, SF, CHI, GB, DET.

PLAN 3: East: NYG, PHI, WAS, DAL, STL: Central: CHI, GB, DET, MIN; West: LA, SF, ATL, NO.

PLAN 4: East: NYG, PHI, WAS, STL, MIN; Central: CHI, GB, DET, ATL; West: LA, SF, DAL, NO.

PLAN 5: East: NYG, PHI, WAS, DET, MIN; Central: CHI, GB, DAL, STL; West: LA, SF, ATL, NO.[31]

These five combinations were written up on slips of paper, sealed into envelopes and put into a fish bowl[32] (other sources say a flower vase), and the official NFC alignment—Plan 3—was pulled out by Rozelle's secretary, Thelma Elkjer.[33] Of the five plans considered, the one that was put into effect was the only one which had Minnesota remaining in the Central Division and Dallas playing in the Eastern Division. This preserved the Vikings' place with geographical rivals Chicago, Detroit, and Green Bay, and the Cowboys' rivalries with the Redskins, Eagles and Giants. It also was the only one of the final five proposals in which there were no warm weather cities in the Central Division. More controversially, the new alignment put both of the two newest NFC franchises, the Saints and Falcons from the Deep South, with the 49ers and Rams. The Falcons had already been playing the California teams in the NFL Coastal Division, but the Saints were in the NFL Capitol Division (with Dallas, Washington, Philadelphia) of the Eastern Conference and now faced two trips to the West Coast per season. The Rams were expected to dominate the West, but the 49ers won the division in its first three seasons before the Rams won the next seven titles (the Falcons did not win the division until 1980, and the Saints not until 1991).

Meanwhile, all three of the major television networks signed contracts to televise games, thus ensuring the combined league's stability. CBS agreed to broadcast all games where an NFC team was on the road, NBC agreed to broadcast all games where an AFC team was on the road, and ABC agreed to broadcast Monday Night Football, making the NFL the first league to have a regular series of national telecasts in prime time.

Aftermath

Many observers believe that the NFL got the better end of the bargain, as Oakland Raiders owner Al Davis and New York Jets owner Sonny Werblin resisted the indemnity payments.

Long-time sports writer Jerry Magee of the San Diego Union-Tribune wrote: "Al Davis taking over as commissioner was the strongest thing the AFL ever did. He thought the AFL–NFL merger was a detriment to the AFL." However, other observers consider those scenarios far-fetched: the NFL had a richer television contract at the time of the merger, in large part because of market exclusivity in such leading population centers as Los Angeles, Chicago, Detroit, Philadelphia, Washington, Baltimore, and Atlanta and Dallas–Fort Worth, which were rapidly increasing in population and would emerge as media strongholds in the 1970s.

On the other hand, the AFL had teams in cities that were not among the nation's leading media markets, such as Miami (the only major professional sports franchise in Florida until the addition of the Buccaneers in 1976), Buffalo, and Denver (all of which at the time had no other major league teams), and Kansas City (which at the time had only a failing baseball team that was ultimately relocated). Other than the shared New York and Bay Area markets, the AFL's largest market was Houston, where the Oilers had little following outside southeast Texas due to the Cowboys' emergence. Most American Football League fans wanted to see an annual interleague championship with the NFL, but many neither expected not favored a full merger and were thus left disappointed because they wanted their league to continue. Those feelings were reinforced when American Football League teams won the final two AFL–NFL World Championship games after the 1968 and 1969 seasons.

Nevertheless, despite the AFL triumphs in Super Bowls III and IV, the old-guard NFL was still widely expected to dominate the merged league over the course of an entire season. In 1970, these predictions were proven to be more or less correct: out of 60 regular season games pitting old-line NFL teams versus former AFL teams, former AFL teams went 19–39 (two games, Buffalo at Baltimore in week 9 and St. Louis at Kansas City in week 10, ended in ties). Only Oakland managed to post a winning record against old-line NFL opposition, going 3–2 (defeating Washington, Pittsburgh and Cleveland; losing to Detroit and San Francisco) before losing to the Colts in the AFC championship. Nevertheless, out of the three NFL teams to join the AFC, only the Colts managed to secure a playoff berth. The Browns and Steelers both missed out due to a stunning second-half performance by the Cincinnati Bengals, who overcame a 1–6 start and their two old-guard division rivals to secure the first-ever NFL playoff berth for a third year expansion team. Ultimately however, it was the Colts who were triumphant—they defeated both the Bengals and Raiders to become the first team to represent the AFC in a post-merger Super Bowl, where they defeated the Dallas Cowboys 16–13 to win Super Bowl V, the franchise's last NFL championship in Baltimore and last overall until 2006.

Even the undefeated Miami Dolphins were slight underdogs to the old-guard Washington Redskins in Super Bowl VII, but Miami won 14–7 to cap the only perfect championship season in NFL history. Not until Super Bowl VIII in 1974 was a former AFL team favored to win the Vince Lombardi Trophy, with the Dolphins trouncing the Minnesota Vikings 24–7 to repeat as champions; the Dolphins were also the first former AFL team to win a Super Bowl championship (and represent the AFC) after the merger. It took until Super Bowl XI in 1977 for an original AFL team to win a post-merger NFL championship, when the Oakland Raiders did so.

Each of the first 29 games on Monday Night Football featured at least one team from the old-guard NFL, with the first nationally televised prime time game between two former AFL teams being Oakland at Houston on October 9, 1972.

Eventually, the AFC teams caught and passed the NFC during the mid- to late-1970s. But even then, NFL proponents claimed that the three NFL teams that joined the AFL to form the AFC were largely the reason. Altogether, these teams played in each of the first three AFC Championship Games, and in eight of the first ten games (out of which they won five).

However, while the Colts and Browns were respectable playoff contenders during this period, it was the Steelers who dominated the league, winning four Super Bowls in six years in 1974–1979. From the perspective of AFL proponents, this was not a continuation of "old NFL" dominance. Before the merger, the Steelers had been perennially close to or in last place in the NFL since their foundation in 1933, including a 1–13 record in 1969 (tied with the Chicago Bears for the worst record in the NFL), with only eight winning seasons and just one playoff appearance (in 1947, where they were shut out) in that time.

The $3 million relocation fee that the Steelers received for joining the AFC after the merger, along with a new stadium and winning a coin-flip tiebreaker against the Bears for the number-one pick in the 1970 NFL draft (which ended up being future Hall of Fame quarterback Terry Bradshaw) helped them rebuild into a team that could compete with the other "old NFL" teams.[34]

The merger paved the way for a new era of prosperity for the NFL. While a number of rival major professional football leagues have commenced play since 1970 including the XFL, WFL, USFL and UFL, and while the CFL once experimented with U.S.-based teams, none of these ventures came close to being a serious challenge to the NFL. The aforementioned U.S. leagues folded outright after one, two, three and four seasons respectively, while the CFL reverted to being an all-Canadian league after three seasons.

While the Buccaneers joined the AFC in 1976, the Seahawks joined the NFC. The 1976 expansion teams switched conference before their second season in the league, becoming the first NFL teams to change conferences after the merger; the Seahawks returned to the NFC in 2002 upon the league's realignment that year.

Four more NFL teams that were not specified in the merger agreement would be established between 1995 and 2002:

- The Carolina Panthers and Jacksonville Jaguars were awarded franchises in 1993 and began play in the NFC and AFC respectively in 1995. Their establishment allowed the league to have divisions of equal size (six divisions of five teams each) for the first time since the merger.

- The Baltimore Ravens started play in 1996, as a result of the controversy stemming from Art Modell's attempt to relocate the Browns to Baltimore. Subsequent legal actions saw a unique compromise in which he was only allowed to take the players, coaches, and front office staff to Baltimore (even then, not all of them made the move), and the Browns' team colors, uniforms, and history would remain in Cleveland to be inherited by the resurrected Browns franchise. As a result, although it was effectively a continuation of the football organization that operated in Cleveland until 1995, Modell's Baltimore team is reckoned to be an expansion franchise that commenced play in 1996. Meanwhile, the club in Cleveland, although it was effectively a brand new football organization stocked by an expansion draft, is recognized to be a continuation of the franchise that commenced play in 1946 and joined the NFL in 1950. The agreement with the NFL was contingent on finding a new owner and the completion of a new stadium in Cleveland, as a result, the Browns were officially reckoned to have "suspended operations" for three years and the number of active NFL teams did not increase to 31 until the 1999 season. Prior to the Browns' reactivation, the NFL briefly considered re-aligning the AFC into four divisions of four teams each while leaving the NFC alignment unchanged. Due in large part to the difficulties an uneven number of divisions would have caused for scheduling inter-conference games, the proposed AFC re-alignment was shelved. As a result, the Browns were placed back in the AFC Central, which expanded to six teams as a result.

- The Houston Texans joined in 2002, after Houston was left without the NFL for five years following the Oilers' move to Nashville, Tennessee, where they eventually became the Tennessee Titans. The Texans' establishment made feasible the realignment of both conferences into four divisions of four teams each, which allows every team to play every other team at least twice over an 8-year span (once at home, once on the road). Houston was once again placed in the AFC. To make room for the Texans, the Seattle Seahawks agreed to return to the NFC.

In total, out of the first 47 AFC Championship Games, sixteen have featured two former AFL teams and 45 have featured at least one former AFL team—the only exceptions being the 1995 championship game between the Steelers and Colts, and the 2008 game between the Steelers and Ravens. Out of the first 46 post-merger Super Bowls, former AFL teams have won 12, lost 21 and did not qualify for the remaining 13. The latter 13 games have all involved one of the three "old guard" organizations that joined the AFC in 1970, with the Steelers playing in eight, the Colts in three (one representing Baltimore and two representing Indianapolis) and the Ravens in two.

Somewhat ironically, the two AFL teams that won Super Bowls prior to the merger (the Jets and Chiefs) were also the last two former AFL teams that had never played in a post-merger championship game. (The Chiefs broke that streak in 2020, when they appeared in Super Bowl LIV.) Four extant NFL teams have yet to reach the Super Bowl at all, including two pre-merger NFL franchises (the Browns and Lions) and two post-merger expansion teams (the Jaguars and Texans). The Houston Oilers never reached a post-merger championship game prior to relocating to Tennessee, thus making Houston the only AFL city that has yet to send a team to the Super Bowl.

In spite of Rozelle's promise that there would be no re-locations involving teams in existence at the time of the merger, by the end of his tenure as commissioner in 1989 three franchises had moved to a different market from where they were based in 1970 (although the league did take legal action in an unsuccessful attempt to prevent the first such move, that of the Raiders, from taking place).

As of 2021, six NFL franchises (the Raiders, Colts, Cardinals, Rams, Oilers/Titans and Chargers) have been involved in post-merger re-locations while an additional franchise (the Browns) temporarily suspended operations as an alternative to re-location. Of the six teams that have re-located since the merger, two (the Raiders and Rams) have returned to the cities they played in at the time of the merger, while the other teams only moved once. However, the Chargers, who had moved to San Diego in 1961 before the merger, returned to Los Angeles in 2017, making them the only team to go through a relocation as a member of both leagues. Also, the Raiders moved a third time, leaving Oakland once more, this time for Las Vegas in 2020.[35]

Broken down by where they played in 1969 and 1970:

- Of the ten teams that competed in the AFL in 1969, seven have been continuously based in their 1969 market, one (the Raiders) returned to their original city after moving to a different city post-merger, one (the Oilers) no longer plays in their original city and one (the Chargers) has returned to its original AFL city after a relocation that took place before the merger. However, the Raiders moved a third time, leaving Oakland for Las Vegas in 2020.[35]

- Of the thirteen teams that formed the NFC in 1970, eleven have been continuously based in their 1969 market, one (the Rams) again play in their pre-merger city after moving to a different city and one (the Cardinals) no longer plays in the city it was based in at the time of the merger.

- Of the three 1969 NFL teams that joined the AFC in 1970, one (the Steelers) has been continuously based in its 1969 market, one (the Browns) plays in its original city after having suspended operations since the merger and one (the Colts) no longer plays in its original city.

The Rams' return from St. Louis to Los Angeles ended an interval lasting 21 years in which there was no NFL team in Los Angeles—the longest such period involving any NFL city of the post-merger era—and resulted in St. Louis replacing Los Angeles as the only 1969 NFL city without a current NFL team. The NFL has not simultaneously fielded teams in all sixteen of its 1969 markets since the Colts relocated to Indianapolis after the 1983 season. It had fielded teams in all ten 1969 AFL cities from the 2002 season (when the Texans joined the league) until the conclusion of the 2016 season (when the Chargers returned to Los Angeles, leaving San Diego without an NFL team).

Neither Portland nor Memphis (the cities that were due to receive AFL franchises via relocation in the rejected 1964 merger proposal) have received an NFL franchise as of 2021. Memphis in particular has made repeated bids for an NFL team (including the Memphis Hound Dogs and the Memphis Grizzlies court case), but all have failed. Memphis would later serve as a temporary home to the Tennessee Oilers for the 1997 season following their departure from Houston. The agreement was originally slated to last for two seasons, but lackluster fan support in Memphis caused the arrangement to be cut short.

Proliferation of new stadiums

A league rule passed as a result of the merger required all NFL teams to use stadiums that seated over 50,000 spectators. At the time, several teams had stadiums that were not up to that standard (see above). Most either built a new stadium by 1971 or, in the case of Chicago, moved to an existing stadium in the metro area that met the requirement. The Buffalo Bills situation would prove to be a pattern for later teams; Buffalo interests were very slow to come to an agreement on a new stadium, and it was only after Bills owner Ralph Wilson began arranging for a move to Seattle (a tactic that would later be used by many other teams in their quests for new stadiums in their hometowns, later using cities such as Los Angeles and San Antonio) that Western New York finally agreed to build Rich Stadium, which opened in 1973.

The Super Bowl has been used as an incentive by the league to convince local governments, businesses, and voters to support the construction, seat licenses and taxes associated with new or renovated stadiums. Therefore, the league has and continues to award Super Bowls to cities that have built new football stadiums for their existing franchises, though all outdoor Super Bowls continued to be played in warmer climates, with the exception of Super Bowl XLVIII played in the new Meadowlands stadium.

Only eight Super Bowls since 1983 have been played in stadiums used by three of these expansion teams: five in Tampa (two at Tampa Stadium and three at Raymond James Stadium), one in Jacksonville and two in Houston.

In some cases, cities have been selected as provisional Super Bowl sites, with the construction or renovation of a suitable facility as a major requirement for hosting the actual game. In the past, New York City and San Francisco have each received provisional site awards. In both cities, the league moved the game to a different site when public funding initiatives failed. The most recent provisional site award went to Kansas City for a Super Bowl to be played in 2015 in Arrowhead Stadium, but Kansas City withdrew their request because the funding for the new roof failed in an April 2006 referendum.

The Kansas City Chiefs, Cleveland Browns, Cincinnati Bengals, Denver Broncos, Houston Texans, Pittsburgh Steelers, Philadelphia Eagles, Chicago Bears, Tampa Bay Buccaneers, Seattle Seahawks, Detroit Lions, Arizona Cardinals, Indianapolis Colts and Minnesota Vikings are all teams who have received a significant amount of public financing to either construct or upgrade the stadiums in which they currently play.

The state of Louisiana has been making cash payouts to the New Orleans Saints since 2001 in order to keep the team from moving. The state received over $185 million from the Federal Emergency Management Agency and other sources to repair and renovate the Superdome following damage from Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Louisiana then began a five-year, $320 million renovation project for the stadium in 2006; another $450 million renovation began in 2020 to upgrade the facility for Super Bowl LIX in February 2025.

In addition, St. Louis and Baltimore also publicly financed stadiums for the purpose of luring the former Los Angeles Rams and the first incarnation of the Cleveland Browns. The Rams returned to Los Angeles in 2016 following the 2015 season and moved into a new stadium in Inglewood, California in 2020 alongside the Chargers who also relocated to the city from San Diego in 2017. The Raiders would move from Oakland once more, this time to Las Vegas with a new stadium built there in 2020.

Similar moves in other sports

Entrepreneurs interested in other sports in North America would follow the AFL's example in competing with the established "major" leagues.

- Baseball: In 1959, the Continental League was proposed by William Shea as a third major league for baseball scheduled to begin play in the 1961 season.[36] Unlike predecessor competitors such as the Players' League and the Federal League, it sought membership within organized baseball's existing organization and acceptance within Major League Baseball (as any attempt at outsider leagues could be quashed as per a 1922 Supreme Court case declaring MLB exempt from federal antitrust laws[37]). The league disbanded in August 1960 without playing a single game, as the other two leagues acquiesced to many of the owners' demands by granting franchises within the two existing leagues. In order to stop the new league, each league allowed that they would be adding two new teams each, three of which ended up in the prospective CL cities of Minneapolis–St. Paul, Houston, and New York City. All proposed CL cities, except Buffalo, would later be granted MLB teams.

- Basketball: In 1967, the American Basketball Association was formed with the explicit intent of merging teams with the National Basketball Association. In 1976, four of the six remaining teams of the ABA—the Denver Nuggets, Indiana Pacers, New York Nets and San Antonio Spurs—were merged into the NBA. All the teams have remained in the same media markets since entering the NBA. In 1975 and 1976, the ABA proposed a championship game between the leagues at the end of the season much like the NFL-AFL championship, but the NBA turned each offer down. Today, except for Virginia, Kentucky, Pittsburgh, St. Louis and any temporary locations ABA teams played in (including teams that were regional teams), all former ABA cities now have NBA teams.

- Ice hockey: In 1972, the World Hockey Association formed to compete with the National Hockey League.[38] The two entities merged in 1979, with four of the six remaining teams—the Edmonton Oilers, Hartford Whalers, Quebec Nordiques and the original Winnipeg Jets—joining the NHL. However, only one of these former WHA teams, the Oilers, is still in its original market. The Nordiques became the Colorado Avalanche in 1995,[39] the Jets became the Phoenix Coyotes in 1996, and Whalers became the Carolina Hurricanes in 1997. The NHL eventually returned to Winnipeg in 2011 when the Atlanta Thrashers became the current incarnation of the Winnipeg Jets.[40]

References

- "NFL and AFL announce merger". The History Channel.

- "How merger will operate". Milwaukee Sentinel. Associated Press. June 9, 1966. p. 4, part 2.

- "How NFL, AFL will run from single wing". Miami News. Associated Press. June 9, 1966. p. 16A.

- Schramm, Tex (June 20, 1966). "Here's how it happened". Sports Illustrated: 14. Retrieved May 21, 2016.

- Maule, Tex (January 1960). "The shaky new league". Sports Illustrated: 49. Archived from the original on February 3, 2014. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- "Legends". Archived from the original on February 3, 2014. Retrieved 2013-06-03.

- "Events & discoveries: Texas competition". Sports Illustrated: 37. September 14, 1959.

- Eskenazi, Gerald (December 15, 2006). "Lamar Hunt, a force in football, dies at 74". The New York Times. Retrieved January 22, 2014.

- "Hunt reports NFL offer of franchise". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. September 10, 1959. p. 16.

- "New pro football league organized". The Gettysburg Times. Associated Press. August 15, 1959. p. 5.

- Mallozzi, Vincent M. (September 17, 2006). "Defending and remembering the A.F.L." The New York Times. Retrieved June 6, 2014.

- "Two types of footballs for Super Bowl". Chicago Tribune. Associated Press. January 15, 1967. p. 1, sec. 2.

- "J6-V". Remember the AFL. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- "Television's next on pro ball agenda". Miami News. Associated Press. March 27, 1960. p. 3C.

- "American Football League may be expanded in 1966". Nashua Telegraph. Associated Press. May 23, 1964. p. 8.

- Full Color Football: The History of the American Football League

- Hand, Jack (May 18, 1966). "Giants sign Bills Pete Gogolak; move could provoke pro grid war". Lewiston Daily Sun. Associated Press. p. 13.

- Curran, Bob (September 11, 1966). "The truth behind pro football's merger". Spartanburg Herald-Journal. p. 6.

- Mann, Jimmy (October 25, 1966). "Gogolak brings serfs forward". St. Petersburg Times. p. 3C.

- Shrake, Edwin (August 29, 1966). "The fabulous Brodie caper". Sports Illustrated: 16.

- "Roman Gabriel says he belongs to Rams, not Raiders". Sumter Daily Item. Associated Press. May 27, 1966. p. 10.

- "The AFL–NFL merger was almost booted... by a kicker". NFL.com.

- "When Lombardi sacked Milwaukee's bid to land a pro football franchise". jsonline.com.

- "Super Bowl covers". National Football League. Retrieved January 22, 2014.

- Grey Beard (April 17, 2017). "Lost Treasures of NFL Films-Episode 4: The American Football League" – via YouTube.

- "Woodard new boss in AFL power shift". Milwaukee Journal. Associated Press. July 26, 1966. p. 13, part 2.

- "Art Modell interim president for NFL". Miami News. Associated Press. May 27, 1967. p. 1B.

- "Congress OK's grid merger". Eugene Register-Guard. (Oregon). Associated Press. October 21, 1966. p. 2B.

- "Paul Brown". Conigliofamily.com. Retrieved December 16, 2013.

- Bledsoe, Terry (December 21, 1969). "Pro football's realignment is already behind schedule". Milwaukee Journal. p. 3, part 2.

- Cooper Rollow (January 17, 1970). "Rozelle Lottery Leaves Bears 'Cold': Realignment Keeps Central Group Intact". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 21, 2016.

- Anderson, Dave (February 27, 2000). "Sports of The Times; The Woman Who Aligned the N.F.C. Teams". The New York Times. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- "Secretary solves pro grid hassle". Beaver County Times. Pennsylvania. United Press International. January 17, 1970. p. B3.

- Sherrington, Kevin (February 1, 2011). "Dallas meeting in '66 saved Steelers from stinking". Dallas Morning News. Retrieved February 6, 2011.

- "NFL owners approve Raiders' move to Las Vegas". NFL.com.

- "Continental League of baseball announced..." rarenewspapers.com.

- Calcaterra, Craig (May 29, 2019). "Happy birthday to baseball's antitrust exemption". NBC Sports. Retrieved November 10, 2021.

What is still in place, firmly, is Major League Baseball’s ability to work to thwart competitors, if any ever arise, and its ability to carve out protected geographic territories for its clubs and anti-competitive contract rights for its clubs.

- "World Hockey Association History". Connecticut Hockey Hall of Fame and Museum. Archived from the original on December 2, 2013.

- "Colorado Avalanche - Team". nhl.com. June 30, 2013. Archived from the original on June 30, 2013.

- "Atlanta Loses Thrashers as N.H.L. Returns to Winnipeg". The New York Times. June 1, 2011.

External links

- Magee, Jerry (February 22, 2004). "Rozelle's Pledge to Congress Gets Swept Under Rug". San Diego Union-Tribune. Archived from the original on April 30, 2006.

- NFL History by Decade