Addison's disease

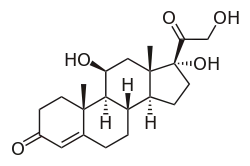

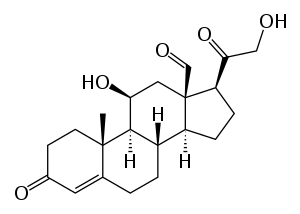

Addison's disease, also known as primary adrenal insufficiency,[4] is a rare long-term endocrine disorder characterized by inadequate production of the steroid hormones cortisol and aldosterone by the two outer layers of the cells of the adrenal glands (adrenal cortex), causing adrenal insufficiency.[5] Symptoms generally come on slowly and insidiously and may include abdominal pain and gastrointestinal abnormalities, weakness, and weight loss.[1] Darkening of the skin in certain areas may also occur.[1] Under certain circumstances, an adrenal crisis may occur with low blood pressure, vomiting, lower back pain, and loss of consciousness.[1] Mood changes may also occur. Rapid onset of symptoms indicates acute adrenal failure which is a serious and emergent condition.[5] An adrenal crisis can be triggered by stress, such as from an injury, surgery, or infection.[1]

| Addison's disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Addison disease, primary adrenal insufficiency,[1] primary adrenocortical insufficiency, chronic adrenal insufficiency, chronic adrenocortical insufficiency, primary hypocorticalism, primary hypocortisolism, primary hypoadrenocorticism, primary hypocorticism, primary hypoadrenalism |

| |

| Darkening of the skin seen on the legs of a patient with an excess of melanin. | |

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

| Symptoms | Abdominal pain, weakness, weight loss, darkening of the skin[1] |

| Complications | Adrenal crisis[1] |

| Usual onset | Middle-aged females[1] |

| Causes | Problems with the adrenal gland[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood tests, urine tests, medical imaging[1] |

| Treatment | Synthetic Corticosteroid such as hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone[1][2] |

| Frequency | 0.9–1.4 per 10,000 people (developed world)[1][3] |

| Deaths | Doubles risk of death |

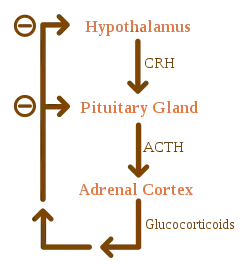

Addison's disease arises from problems with the adrenal gland such that not enough of the steroid hormone cortisol and possibly aldosterone are produced.[1] In developed countries, the etiology of Addison's disease is often attributed to idiopathic damage by the body's own immune system, and in developing countries most often due to tuberculosis.[6] Other causes include certain medications, sepsis, and bleeding into both adrenal glands.[1][6] Secondary adrenal insufficiency is caused by not enough adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) (produced by the pituitary gland) or corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) (produced by the hypothalamus).[1] Despite this distinction, adrenal crises can happen in all forms of adrenal insufficiency.[1] Addison's disease is generally diagnosed by blood tests, urine tests, and medical imaging.[1]

Addison's disease can be described in association with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis, acquired hypoparathyroidism, diabetes mellitus, pernicious anemia, hypogonadism, chronic and active hepatitis, malabsorption, immunoglobulin abnormalities, alopecia, vitiligo, spontaneous myxedema, Graves' disease, and chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis.[7]

Treatment involves replacing the absent hormones.[1] This involves taking a synthetic corticosteroid, such as hydrocortisone or fludrocortisone.[1][2] These medications are usually taken by mouth.[1] Lifelong, continuous steroid replacement therapy is required, with regular follow-up treatment and monitoring for other health problems.[8] A high-salt diet may also be useful in some people.[1] If symptoms worsen, an injection of corticosteroid is recommended and people should carry a dose with them.[1] Often, large amounts of intravenous fluids with the sugar dextrose are also required.[1] Without treatment, an adrenal crisis can result in death.[1]

Addison's disease affects about 9 to 14 per 100,000 people in the developed world.[1][3] It occurs most frequently in middle-aged females.[1] Secondary adrenal insufficiency is more prevalent.[3] Long-term outcomes with treatment are typically favorable.[9] It is named after Thomas Addison, a graduate of the University of Edinburgh Medical School, who first described the condition in 1855.[10] The adjective "addisonian" is used to describe features of the condition, as well as people with Addison's disease.[11]

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms of Addison's disease generally develop gradually.[12] Symptoms may include fatigue, muscle weakness, weight loss, nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, lightheadedness upon standing, irritability, depression, and diarrhea.[12] Some people have cravings for salty foods due to the loss of sodium through their urine.[11][12] Hyperpigmentation of the skin may be seen, particularly when the person lives in a sunny area, as well as darkening of the palmar crease, sites of friction, recent scars, the vermilion border of the lips, and genital skin.[13] These skin changes are not encountered in secondary and tertiary hypoadrenalism.[14]

- Skin changes

- Hyperpigmentation of the skin

- Vitiligo

- Gastrointestinal changes

- Nausea and vomiting

- Weight loss

- Abdominal pain

- Less common but still occurring: malnutrition and muscle wasting

- Behavioral disorders

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Irritability

- Poor concentration

- Changes in females

- Loss or irregularity of menstrual cycle

- Loss of body hair

- Decreased sexual drive[5]

On physical examination, these clinical signs may be noticed:[11]

- Low blood pressure with or without orthostatic hypotension (blood pressure that decreases with standing)

- Darkening (hyperpigmentation) of the skin, including areas not exposed to the sun – characteristic sites of darkening are skin creases (e.g., of the hands), nipple, and the inside of the cheek (buccal mucosa); also, old scars may darken. This occurs because melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH) and ACTH share the same precursor molecule, pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC). After production in the anterior pituitary gland, POMC gets cleaved into gamma-MSH, ACTH, and beta-lipotropin. The subunit ACTH undergoes further cleavage to produce alpha-MSH, the most important MSH for skin pigmentation. In secondary and tertiary forms of adrenal insufficiency, skin darkening does not occur, as ACTH is not overproduced.

Addison's disease is associated with the development of other autoimmune diseases, such as type I diabetes, thyroid disease (Hashimoto's thyroiditis), celiac disease, or vitiligo.[15][16] Addison's disease may be the only manifestation of undiagnosed celiac disease.[15] Both diseases share the same genetic risk factors (HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8 haplotypes).[17]

The presence of Addison's in addition to mucocutaneous candidiasis, hypoparathyroidism, or both, is called autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1.[18] The presence of Addison's in addition to autoimmune thyroid disease, type 1 diabetes, or both, is called autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 2.[19]

Adrenal crisis

An "adrenal crisis" or "addisonian crisis" is a constellation of symptoms that indicates severe adrenal insufficiency. This may be the result of either previously undiagnosed Addison's disease, a disease process suddenly affecting adrenal function (such as adrenal hemorrhage), or an intercurrent problem (e.g., infection, trauma) in someone known to have Addison's disease. It is a medical emergency and potentially life-threatening situation requiring immediate emergency treatment.[20]

Characteristic symptoms are:[12]

- Sudden penetrating pain in the legs, lower back, or abdomen

- Severe vomiting and diarrhea, resulting in dehydration

- Low blood pressure

- Syncope (loss of consciousness and ability to stand)

- Hypoglycemia (reduced level of blood glucose)

- Confusion, psychosis, slurred speech

- Severe lethargy

- Hyponatremia (low sodium level in the blood)

- Hyperkalemia (elevated potassium level in the blood)

- Hypercalcemia (elevated calcium level in the blood)

- Convulsions

- Fever

Causes

Causes of adrenal insufficiency can be categorized by the mechanism through which they cause the adrenal glands to produce insufficient cortisol. This can be due to damage or destruction of the adrenal cortex. These deficiencies include glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid hormones as well. These are adrenal dysgenesis (the gland has not formed adequately during development), impaired steroidogenesis (the gland is present but is biochemically unable to produce cortisol), or adrenal destruction (disease processes leading to glandular damage).[11]

Adrenal destruction

Autoimmune adrenalitis is the most common cause of Addison's disease in the industrialized world. Autoimmune destruction of the adrenal cortex is caused by an immune reaction against the enzyme 21-hydroxylase (a phenomenon first described in 1992).[21] This may be isolated or in the context of autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome (APS type 1 or 2), in which other hormone-producing organs, such as the thyroid and pancreas, may also be affected.[22]

Adrenal destruction is also a feature of adrenoleukodystrophy, and when the adrenal glands are involved in metastasis (seeding of cancer cells from elsewhere in the body, especially lung), hemorrhage (e.g., in Waterhouse–Friderichsen syndrome or antiphospholipid syndrome), particular infections (tuberculosis, histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis), or the deposition of abnormal protein in amyloidosis.[23]

Adrenal dysgenesis

All causes in this category are genetic, and generally very rare. These include mutations to the SF1 transcription factor, congenital adrenal hypoplasia due to DAX-1 gene mutations and mutations to the ACTH receptor gene (or related genes, such as in the Triple-A or Allgrove syndrome). DAX-1 mutations may cluster in a syndrome with glycerol kinase deficiency with a number of other symptoms when DAX-1 is deleted together with a number of other genes.[11]

Impaired steroidogenesis

To form cortisol, the adrenal gland requires cholesterol, which is then converted biochemically into steroid hormones. Interruptions in the delivery of cholesterol include Smith–Lemli–Opitz syndrome and abetalipoproteinemia.Of the synthesis problems, congenital adrenal hyperplasia is the most common (in various forms: 21-hydroxylase, 17α-hydroxylase, 11β-hydroxylase and 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase), lipoid CAH due to deficiency of StAR and mitochondrial DNA mutations.[11] Some medications interfere with steroid synthesis enzymes (e.g., ketoconazole), while others accelerate the normal breakdown of hormones by the liver (e.g., rifampicin, phenytoin).[11]

Diagnosis

Suggestive features

Routine laboratory investigations may show:[11]

- Low blood sugar (worse in children due to loss of glucocorticoid's glucogenic effects)

- Low blood sodium, due to loss of production of the hormone aldosterone, to the kidney's inability to excrete free water in the absence of sufficient cortisol, and also the effect of corticotropin-releasing hormone to stimulate secretion of ADH.

- High blood potassium, due to loss of production of the hormone aldosterone.

- Eosinophilia and lymphocytosis (increased number of eosinophils or lymphocytes, two types of white blood cells)

- Metabolic acidosis (increased blood acidity), also is due to loss of the hormone aldosterone because sodium reabsorption in the distal tubule is linked with acid/hydrogen ion (H+) secretion. Absent or insufficient levels of aldosterone stimulation of the renal distal tubule lead to sodium wasting in the urine and H+ retention in the serum.

Testing

In suspected cases of Addison's disease, demonstration of low adrenal hormone levels even after appropriate stimulation (called the ACTH stimulation test or synacthen test) with synthetic pituitary ACTH hormone tetracosactide is needed for the diagnosis. Two tests are performed, the short and the long test. Dexamethasone does not cross-react with the assay and can be administered concomitantly during testing.[24][25]

The short test compares blood cortisol levels before and after 250 micrograms of tetracosactide (intramuscular or intravenous) is given. If one hour later, plasma cortisol exceeds 170 nmol/L and has risen by at least 330 nmol/L to at least 690 nmol/L, adrenal failure is excluded. If the short test is abnormal, the long test is used to differentiate between primary adrenal insufficiency and secondary adrenocortical insufficiency.[26]

The long test uses 1mg tetracosactide (intramuscular). Blood is taken 1, 4, 8, and 24 hours later. Normal plasma cortisol level should reach 1,000 nmol/L by 4 hours. In primary Addison's disease, the cortisol level is reduced at all stages, whereas in secondary corticoadrenal insufficiency, a delayed but normal response is seen. Other tests may be performed to distinguish between various causes of hypoadrenalism, including renin and adrenocorticotropic hormone levels, as well as medical imaging – usually in the form of ultrasound, computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging.[26]

Adrenoleukodystrophy, and the milder form, adrenomyeloneuropathy, cause adrenal insufficiency combined with neurological symptoms. These diseases are estimated to be the cause of adrenal insufficiency in about 35% of diagnosed males with idiopathic Addison's disease and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of any male with adrenal insufficiency. Diagnosis is made by a blood test to detect very long-chain fatty acids.[27]

Treatment

Maintenance

Treatment for Addison's disease involves replacing the missing cortisol, sometimes in the form of hydrocortisone tablets, or prednisone tablets in a dosing regimen that mimics the physiological concentrations of cortisol. Alternatively, one-quarter as much prednisolone may be used for equal glucocorticoid effect as hydrocortisone. Treatment is usually lifelong. In addition, many people require fludrocortisone as a replacement for the missing aldosterone.[20]

People with Addison's are often advised to carry information on them (e.g., in the form of a MedicAlert bracelet or information card) for the attention of emergency medical services personnel who might need to attend to their needs.[28][29] A needle, syringe, and injectable form of cortisol are also recommended to be carried for emergencies.[29] People with Addison's disease are advised to increase their medication during periods of illness or when undergoing surgery or dental treatment.[29] Immediate medical attention is needed when severe infections, vomiting, or diarrhea occur, as these conditions can precipitate an Addisonian crisis. A person who is vomiting may require injections of hydrocortisone, instead.[30]

Those with low aldosterone levels may also benefit from a high-sodium diet. It may also be beneficial for the people with Addison's disease to increase their dietary intake of calcium and vitamin D. High dosages of corticosteroids are linked to osteoporosis so these may be necessary for bone health.[31] Sources of calcium include dairy products, leafy greens, and fortified flours among many others. Vitamin D can be obtained through the sun, oily fish, red meat, and egg yolks among many others. Though there are many sources to obtain vitamin D through your diet, many people choose to use a supplement.

Crisis

Standard therapy involves intravenous injections of glucocorticoids and large volumes of intravenous saline solution with dextrose (glucose). This treatment usually brings rapid improvement. If intravenous access is not immediately available, intramuscular injection of glucocorticoids can be used. When the person can take fluids and medications by mouth, the amount of glucocorticoids is decreased until a maintenance dose is reached. If aldosterone is deficient, maintenance therapy also includes oral doses of fludrocortisone acetate.[32]

Prognosis

Outcomes are typically good when treated. Most can expect to live relatively normal lives. Someone with the disease should be observant of symptoms of an "Addison's crisis" while the body is strained, as in rigorous exercise or being sick, the latter often needing emergency treatment with intravenous injections to treat the crisis.[33]

Individuals with Addison's disease have more than a doubled mortality rate.[34] Furthermore, individuals with Addison's disease and diabetes mellitus have an almost four-fold increase in mortality compared to individuals with only diabetes.[35] The risk ratio for cause mortality in males and females is 2.19 and 2.86, respectively.

Death from individuals with Addison's disease often occurs due to cardiovascular disease, infectious disease, and malignant tumors, among other possibilities.[36]

Epidemiology

The frequency rate of Addison's disease in the human population is sometimes estimated at one in 100,000.[37] Some put the number closer to 40–144 cases per million population (1/25,000–1/7,000).[1][38][39] Addison's can affect persons of any age, sex, or ethnicity, but it typically presents in adults between 30 and 50 years of age.[39][40] Research has shown no significant predispositions based on ethnicity.[38] About 70% of Addison's disease diagnoses occur due to autoimmune reactions, which cause damage to the adrenal cortex.[5]

History

Addison's disease is named after Thomas Addison, the British physician who first described the condition in On the Constitutional and Local Effects of Disease of the Suprarenal Capsules (1855).[41] He originally described it as "melasma suprarenale", but later physicians gave it the medical eponym "Addison's disease" in recognition of Addison's discovery.[42]

While the six under Addison in 1855 all had adrenal tuberculosis,[43] the term "Addison's disease" does not imply an underlying disease process.

The condition was initially considered a form of anemia associated with the adrenal glands. Because little was known at the time about the adrenal glands (then called "Supra-Renal Capsules"), Addison's monograph describing the condition was an isolated insight. As the adrenal function became better known, Addison's monograph became known as an important medical contribution and a classic example of careful medical observation.[44] Tuberculosis used to be a major cause of Addison's disease and acute adrenal failure worldwide. It remains a leading cause in developing countries today.[5]

US president John F. Kennedy suffered from complications of Addison's Disease throughout his life, including during his presidency, resulting in fatigue and hyperpigmentation of the face.

Other animals

Hypoadrenocorticism is uncommon in dogs,[45] and rare in cats, with less than 40 known feline cases worldwide, since first documented in 1983.[46][47] Individual cases have been reported in a grey seal,[48] a red panda,[49] a flying fox,[50] and a sloth.[51]

In dogs, hypoadrenocorticism has been diagnosed in many breeds.[45] Vague symptoms, which wax and wane, can cause delay in recognition of the presence of the disease.[52] Female dogs appear more affected than male dogs, though this may not be the case in all breeds.[52][53] The disease is most often diagnosed in dogs that are young to middle-aged, but it can occur at any age from 4 months to 14 years.[52] Treatment of hypoadrenocorticism must replace the hormones (cortisol and aldosterone) which the dog cannot produce itself.[54] This is achieved either by daily treatment with fludrocortisone, or monthly injections with desoxycorticosterone pivalate (DOCP) and daily treatment with a glucocorticoid, such as prednisone.[54] Several follow-up blood tests are required so the dose can be adjusted until the dog is receiving the correct amount of treatment, because the medications used in the therapy of hypoadrenocorticism can cause excessive thirst and urination if not prescribed at the lowest effective dose.[54] In anticipation of stressful situations, such as staying in a boarding kennel, dogs require an increased dose of prednisone.[54] Lifelong treatment is required, but the prognosis for dogs with hypoadrenocorticism is very good.[52]

References

- "Adrenal Insufficiency and Addison's Disease". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. May 2014. Archived from the original on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- Napier, Catherine; Pearce, Simon H.S. (June 2014). "Current and emerging therapies for Addison's disease". Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Ltd. 21 (3): 147–53. doi:10.1097/med.0000000000000067. PMID 24755997. S2CID 13732181. Archived from the original on 2019-10-31. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- Brandão Neto, RA; de Carvalho, JF (2014). "Diagnosis and classification of Addison's disease (autoimmune adrenalitis)". Autoimmunity Reviews. 13 (4–5): 408–11. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.025. PMID 24424183.

- Oelkers, W. (2000). "Clinical diagnosis of hyper- and hypocortisolism". Noise & Health. 2 (7): 39–48. ISSN 1463-1741. PMID 12689470.

- "Addison's Disease". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Retrieved 2020-12-01.

- Adam, Andy (2014). Grainger & Allison's Diagnostic Radiology (6 ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1031. ISBN 9780702061288. Archived from the original on 14 March 2016.

- Neufeld, Michel; Maclaren, Noel K.; Blizzard, Robert M. (September 1981). "Two Types of Autoimmune Addisonʼs Disease Associated with Different Polyglandular Autoimmune (PGA) Syndromes". Medicine. 60 (5): 355–362. doi:10.1097/00005792-198109000-00003. ISSN 0025-7974. PMID 7024719. S2CID 20641616.

- Napier, Catherine; Pearce, Simon H.S. (December 2012). "Autoimmune Addison's disease". Presse Médicale. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier. 41 (12 P 2): e626-35. doi:10.1016/j.lpm.2012.09.010. PMID 23177474.

- Rajagopalan, Murray Longmore, Ian B. Wilkinson, Supraj R. (2006). Mini Oxford handbook of clinical medicine (6 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 312. ISBN 9780198570714. Archived from the original on 14 March 2016.

- Rose, Noel R.; Mackay, Ian R. (2014). The autoimmune diseases (5 ed.). San Diego, CA: Elsevier Science. p. 605. ISBN 9780123849304. Archived from the original on 14 March 2016.

- Ten S, New M, Maclaren N (2001). "Clinical review 130: Addison's disease 2001". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 86 (7): 2909–2922. doi:10.1210/jcem.86.7.7636. PMID 11443143.

- "Addison's Disease". National Endocrine and Metabolic Diseases Information Service. Archived from the original on 28 October 2007. Retrieved 26 October 2007.

- Freeman, Lynette K.; Chanco Turner, Maria L. (2006). "Addison's disease". Clinics in Dermatology. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier. 24 (4): 276–280. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2006.04.006. PMID 16828409.

- de Herder WW, van der Lely AJ (May 2003). "Addisonian crisis and relative adrenal failure". Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders. 4 (2): 143–7. doi:10.1023/A:1022938019091. PMID 12766542. S2CID 33794590.

- Freeman, Hugh James (2016). "Endocrine manifestations in celiac disease". World Journal of Gastroenterology (Review). Pleasanton, California: Baishideng Publishing Group. 22 (38): 8472–8479. doi:10.3748/wjg.v22.i38.8472. PMC 5064028. PMID 27784959.

- Zhernakova, Alexandra; Withoff, Sebo; Wijmenga, Cisca (2013). "Clinical implications of shared genetics and pathogenesis in autoimmune diseases". Nature Reviews Endocrinology (Review). Berlin, Germany: Springer Nature. 9 (11): 646–59. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2013.161. PMID 23959365. S2CID 28336180.

- Denham, Jolanda M.; Hill, Ivor D. (2013). "Celiac disease and autoimmunity: review and controversies". Current Allergy and Asthma Reports (Review). Berlin, Germany: Springer Science+Business Media. 13 (4): 347–53. doi:10.1007/s11882-013-0352-1. PMC 3725235. PMID 23681421.

- "Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 1 | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 12 April 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- "Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 2 | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 13 April 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- "Adrenal Insufficiency and Addison's Disease". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- Winqvist O, Karlsson FA, Kämpe O (June 1992). "21-Hydroxylase, a major autoantigen in idiopathic Addison's disease". The Lancet. 339 (8809): 1559–62. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(92)91829-W. PMID 1351548. S2CID 19666235.

- Husebye, Eystein S.; Perheentupa, J; Rautemaa, R; Kämpe, O (May 2009). "Clinical manifestations and management of patients with autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type I". Journal of Internal Medicine. 265 (5): 514–29. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02090.x. PMID 19382991. S2CID 205339997.

- Kennedy, Ron. "Addison's Disease". The Doctors' Medical Library. Archived from the original on 12 April 2013. Retrieved 10 April 2013.

- Dorin RI, Qualls CR, Crapo LM (2003). "Diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency" (PDF). Ann. Intern. Med. 139 (3): 194–204. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-139-3-200308050-00017. PMID 12899587.

- Elizabeth H. Holt (2008). "ACTH (cosyntropin) stimulation test".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Addison's Disease". wasiclinic. 2021-07-14. Retrieved 2022-05-27.

- Laureti S, Casucci G, Santeusanio F, Angeletti G, Aubourg P, Brunetti P (1996). "X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy is a frequent cause of idiopathic Addison's disease in young adult male patient". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 81 (2): 470–474. doi:10.1210/jcem.81.2.8636252. PMID 8636252.

- Quinkler M, Dahlqvist P, Husebye ES, Kämpe O (January 2015). "A European Emergency Card for adrenal insufficiency can save lives". European Journal of Internal Medicine. 26 (1): 75–76. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2014.11.006. PMID 25498511.

- Michels A, Michels N (1 April 2014). "Addison disease: early detection and treatment principles". American Family Physician. 89 (7): 563–568. PMID 24695602. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015.

- White, Katherine (28 July 2004). "What to do in an emergency – Addisonian crisis". Addison's Disease Self Help Group. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- "Eating, Diet, and Nutrition for Adrenal Insufficiency & Addison's Disease | NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

- "Adrenal Insufficiency and Addison's Disease". National Endocrine and Metabolic Diseases Information Service. Archived from the original on 26 April 2011. Retrieved 26 November 2010.

- "Addison's disease – Treatment". NHS Choices. Archived from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- Bergthorsdottir, Ragnhildur; Leonsson-Zachrisson, Maria; Odén, Anders; Johannsson, Gudmundur (1 December 2006). "Premature Mortality in Patients with Addison's Disease: A Population-Based Study". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 91 (12): 4849–4853. doi:10.1210/jc.2006-0076. ISSN 0021-972X. PMID 16968806.

- Dimitrios Chantzichristos; Anders Persson; Björn Eliasson; Mervete Miftaraj; Stefan Franzén; Ragnhildur Bergthorsdottir; Soffia Gudbjörnsdottir; Ann-Marie Svensson; Gudmundur Johannsson (1 April 2016). "Patients with Diabetes Mellitus Diagnosed with Addison´s Disease Have a Markedly Increased Additional Risk of Death". Cushing Syndrome and Primary Adrenal Disorders. Meeting Abstracts. Endocrine Society.

- Bergthorsdottir, Ragnhildur; Leonsson-Zachrisson, Maria; Odén, Anders; Johannsson, Gudmundur (2006-12-01). "Premature Mortality in Patients with Addison's Disease: A Population-Based Study". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 91 (12): 4849–4853. doi:10.1210/jc.2006-0076. ISSN 0021-972X. PMID 16968806.

- "Addison Disease". MedicineNet. Archived from the original on 24 June 2007. Retrieved 25 July 2007.

- Odeke, Sylvester. "Addison Disease". eMedicine. Archived from the original on 7 July 2007. Retrieved 25 July 2007.

- "Addison's disease". nhs.uk. 2018-06-22. Retrieved 2020-10-14.

- Volpé, Robert (1990). Autoimmune Diseases of the Endocrine System. CRC Press. p. 299. ISBN 978-0-8493-6849-3.

- Addison, Thomas (1855). On The Constitutional And Local Effects Of Disease Of The Supra-Renal Capsules. London: Samuel Highley. Archived from the original on 14 April 2005.

- Physician and Surgeon. Keating & Bryant. 1885.

- Patnaik MM, Deshpande AK (May 2008). "Diagnosis–Addison's Disease Secondary to Tuberculosis of the Adrenal Glands". Clinical Medicine & Research. 6 (1): 29. doi:10.3121/cmr.2007.754a. PMC 2442022. PMID 18591375.

- Bishop PM (1950). "The history of the discovery of Addison's disease". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 43 (1): 35–42. doi:10.1177/003591575004300105. PMC 2081266. PMID 15409948.

- Klein, Susan C.; Peterson, Mark E. (January 2010). "Canine hypoadrenocorticism: Part I". The Canadian Veterinary Journal. 51 (1): 63–9. PMC 2797351. PMID 20357943.

- 1. Drobatz KJ, Costello MF. Feline Emergency & Critical Care Medicine. Ames, Iowa: Blackwell Publ; 2010. pp. 422–424.

- Lovelace Tofte, Karen (2018). "Chapter 111. Hypoadrenocorticism". In Norsworthy, Gary D. (ed.). The Feline Patient. John Wiley & Sons. p. 324. ISBN 9781119269038.

- Stringfield, Cynthia E.; Garne, Michael; Holshuh, H.J. (2000). Addison's disease in a gray seal (Halichoerus grypus). International Association for Aquatic Animal Medicine Proceedings.

- Sohn, Pam (10 February 2012). "Endangered red panda dies at Chattanooga Zoo". Times Free Press. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- Brock, A. Paige; Hall, Natalie H.; Cooke, Kirsten L.; Reese, David J.; Emerson, Jessica A.; Wellehan, James F.X. Jr (June 2013). "Diagnosis and management of atypical hypoadrenocorticism in a variable flying fox (Pteropus hypomelanus)". Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine. 44 (2): 517–9. doi:10.1638/2012-0276R2.1. PMID 23805580. S2CID 38918707.

- Kline, Sarah; Rooker, Leah; Nobrega-Lee, Michelle; Guthrie, Amanda (March 2015). "Hypoadrenocorticism (Addison's disease) in a Hoffmann's two-toed sloth (Choloepus hoffmanni)". Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine. 46 (1): 171–174. doi:10.1638/2014-0003R2.1. PMID 25831596. S2CID 20775341.

- Scott-Moncrieff, J. Catharine (2015). "Chapter 12: Hypoadrenocorticism". In Feldman, Edward C.; Nelson, Richard W.; Reusch, Claudia E.; Scott-Moncrieff, J. Catharine R. (eds.). Canine and Feline Endocrinology (4th ed.). Saunders Elsevier. pp. 485–520. ISBN 978-1-4557-4456-5.

- Boag, Alisdair; Catchpole, Brian (2014). "A Review of the Genetics of Hypoadrenocorticism". Topics in Companion Animal Medicine. 29 (4): 96–101. doi:10.1053/j.tcam.2015.01.001. PMID 25813849.

- Lathan, Patty; Thompson, Ann L. (2018). "Management of hypoadrenocorticism (Addison's disease) in dogs". Veterinary Medicine: Research and Reports. 9: 1–10. doi:10.2147/VMRR.S125617. PMC 6055912. PMID 30050862.