American bittern

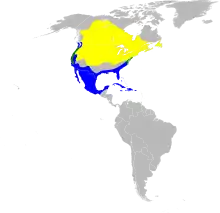

The American bittern (Botaurus lentiginosus) is a species of wading bird in the heron family. It has a Nearctic distribution, breeding in Canada and the northern and central parts of the United States, and wintering in the U.S. Gulf Coast states, all of Florida into the Everglades, the Caribbean islands and parts of Central America.

| American bittern | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Pelecaniformes |

| Family: | Ardeidae |

| Genus: | Botaurus |

| Species: | B. lentiginosus |

| Binomial name | |

| Botaurus lentiginosus (Rackett, 1813) [2] | |

| |

| Range of B. lentiginosus Breeding range Year-round range Wintering range | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

It is a well-camouflaged, solitary brown bird that unobtrusively inhabits marshes and the coarse vegetation at the edge of lakes and ponds. In the breeding season it is chiefly noticeable by the loud, booming call of the male. The nest is built just above the water, usually among bulrushes and cattails, where the female incubates the clutch of olive-colored eggs for about four weeks. The young leave the nest after two weeks and are fully fledged at six or seven weeks.

The American bittern feeds mostly on fish but also eats other small vertebrates as well as crustaceans and insects. It is fairly common over its wide range, but its numbers are thought to be decreasing, especially in the south, because of habitat degradation. However the total population is large, and the International Union for Conservation of Nature has assessed its conservation status as being of "Least Concern".

Description

The American bittern is a large, chunky, brown bird, very similar to the Eurasian bittern (Botaurus stellaris), though slightly smaller, and the plumage is speckled rather than being barred. It is 58–85 cm (23–33 in) in length, with a 92–115 cm (36–45 in) wingspan and a body mass of 370–1,072 g (0.816–2.363 lb).[3][4]

The crown is chestnut brown with the centers of the feathers being black. The side of the neck has a bluish-black elongated patch which is larger in the male than in the female. The hind neck is olive, and the mantle and scapulars are dark chestnut-brown, barred and speckled with black, some feathers being edged with buff. The back, rump, and upper tail-coverts are similar in color but more finely speckled with black and with grey bases to the feathers. The tail feathers are chestnut brown with speckled edges, and the primaries and secondaries are blackish-brown with buff or chestnut tips. The cheeks are brown with a buff superciliary stripe and a similarly colored mustachial stripe. The chin is creamy-white with a chestnut central stripe, and the feathers of the throat, breast, and upper belly are buff and rust-colored, finely outlined with black, giving a striped effect to the underparts. The eyes are surrounded by yellowish skin, and the iris is pale yellow. The long, robust bill is yellowish-green, the upper mandible being darker than the lower, and the legs and feet are yellowish-green. Juveniles resemble adults, but the sides of their necks are less olive.[5]

Taxonomy

The American bittern was first described in 1813 by the English clergyman Thomas Rackett from a vagrant individual he examined in Dorset, England.[6] No extant subspecies are accepted.[6] However, fossils found in the Ichetucknee River in Florida, and originally described as a new form of heron (Palaeophoyx columbiana McCoy, 1963)[7] were later recognized to be a smaller, prehistoric subspecies of the American bittern which lived during the Late Pleistocene (Olson, 1974)[8] and would thus be called B. l. columbianus. Its closest living relative is the pinnated bittern (Botaurus pinnatus) from Central and South America.[6]

The generic name Botaurus was given by English naturalist James Francis Stephens, and is derived from Medieval Latin butaurus, "bittern", constructed from the Middle English name for the Eurasian bittern, botor.[9] Pliny gave a fanciful derivation from Bos (ox) and taurus (bull), because the bittern's call resembles the bellowing of a bull.[10] The species name lentiginosus is Latin for "freckled", from lentigo (freckle), and refers to the speckled plumage.[9]

Many folk names are given for its distinctive call.[11] In his book on the common names of American birds, Ernest Choate lists "bog bumper" and "stake driver".[12] Other vernacular names include "thunder pumper", "bog bull",[13] "bog thumper", "mire drum", and "water belcher".[14]

Distribution and habitat

Its range includes much of North America. It breeds in southern Canada as far north as British Columbia, the Great Slave Lake and Hudson Bay, and in much of the United States and possibly central Mexico. It migrates southward in the fall and overwinters in the southern United States of the Gulf Coast region, most notably in the marshy Everglades of Florida, the Caribbean Islands and Mexico, with past records also coming from Panama and Costa Rica. As a long-distance migrant, it is a very rare vagrant in Europe, including Great Britain and Ireland. It is an aquatic bird and frequents bogs, marshes and the thickly-vegetated verges of shallow-water lakes and ponds, both with fresh and brackish or saline water. It sometimes feeds out in the open in wet meadows and pastures.[5][6]

Behavior

_hiding_in_tall_grass.jpg.webp)

The American bittern is a solitary bird and usually keeps itself well-hidden and is difficult to observe. It usually hunts by walking stealthily in shallow water and among the vegetation, stalking its prey, but sometimes it stands still in ambush. If it senses that it has been seen, it remains motionless, with its bill pointed upward, its cryptic coloration causing it to blend into the surrounding foliage. It is mainly nocturnal and is most active at dusk. More often heard than seen, the male bittern has a loud, booming call that resembles a congested pump and which has been rendered as "oong, kach, oonk".[6] While uttering this sound, the bird's head is thrown convulsively upward and then forward, and the sound is repeated up to seven times.[5]

The process by which the bittern produces its distinctive sound is not fully understood. It has been suggested that the bird gradually puffs out its neck by inflating its esophagus with air accompanied by a mild clicking or hiccuping sound. The esophagus is kept inflated by means of flaps beside the tongue. Once this action is completed and the esophagus is fully inflated, the distinctive gulping sound is made in the syrinx. When the sound is finished, the bird deflates its esophagus.[15]

Like other members of the heron family, the American bittern feeds in marshes and shallow ponds, preying mainly on fish but also consuming amphibians, reptiles, small mammals, crustaceans and insects. It is a territorial bird and has a threat display which involves slowly erecting long, white, previously-concealed, plumes on its shoulders, to form wing-like extensions that nearly meet across its back, resembling a ruff. The bird then stands still in a threatening posture, or stalks the intruder in a crouching position, with its head retracted and a gliding gait.[5]

This bird nests solitarily in marshes among coarse vegetation such as bulrushes and cattails, with the female building the nest and the male guarding it. The nest is usually about 15 cm (6 in) above the water surface and consists of a rough platform of dead stalks and rushes, sometimes with a few twigs mixed in, and lined with bits of coarse grass. Up to about six eggs are laid and are incubated by the female for twenty-nine days. The eggs are bluntly ovoid in shape, olive-buff and unspeckled, averaging 49 by 37 mm (1.93 by 1.46 in) in size. The chicks are fed individually, each in turn pulling down the female's beak and receiving regurgitated food directly into its beak. They leave the nest at about two weeks and are fully-fledged at six to seven weeks.[5]

Status

The bird's numbers are declining in many parts of its range because of habitat loss. This is particularly noticeable in the southern part where chemical contamination and human development are reducing the area of suitable habitat.[13] However, the bird has an extremely large range and a large total population, and the International Union for Conservation of Nature has assessed its conservation status as being of "least concern".[1] The American bittern is protected under the United States Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918.[16] It is also protected under the Canadian Migratory Birds Convention Act of 1994 to which both Canada and the United States are signatories.[17]

References and notes

- BirdLife International (2016). "Botaurus lentiginosus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22697340A93609388. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22697340A93609388.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- Lepage, Denis. "American Bittern Botaurus lentiginosus (Rackett, 1813)". Avibase. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- "American Bittern". All About Birds. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses by John B. Dunning Jr. (Editor). CRC Press (1992), ISBN 978-0-8493-4258-5.

- Witherby, H. F., ed. (1943). Handbook of British Birds, Volume 3: Hawks to Ducks. H. F. and G. Witherby Ltd. pp. 160–162.

- Martínez-Vilalta, A.; Motis, A.; Kirwan, G.M. (2014). "American Bittern (Botaurus lentiginosus)". Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- McCoy, John J. (1963). "The fossil avifauna of Itchtucknee River, Florida" (PDF). Auk. 80 (3): 335–351. doi:10.2307/4082892. JSTOR 4082892.

- Olson, Storrs L. (1974). "A reappraisal of the fossil heron Palaeophoyx columbiana McCoy" (PDF). Auk. 91 (1): 179–180. doi:10.2307/4084689. JSTOR 4084689.

- Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 75, 221. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- "Bittern (1)". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 16 May 2016.(subscription required)

- McAtee, Waldo Lee (1959). Folk-names of Canadian Birds. Bulletin of National Museum of Canada. Vol. 51. National Museum of Canada. p. 6.

- Choate, Ernest Alfred (1985). The Dictionary of American Bird Names. Harvard Common Press. ISBN 978-0-87645-117-5.

- Gardner, Dana; Overcott, Nancy (2007). Fifty Uncommon Birds of the Upper Midwest. University of Iowa Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-58729-590-4.

- Criswell, Rob (2021). "Ghosts of the Marsh". Pennsylvania Game News 92 (6): 14–18.

- Chapin, James, P. (1922). The Function of the Oesophagus in the Bittern's Booming. The Auk, Vol XXXIX. p. 196.

- "List of Migratory Bird Species Protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act as of December 2, 2013". Migratory Bird Program. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- MacDowell, Laurel Sefton (2012). An Environmental History of Canada. UBC Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-7748-2103-2.

Further reading

- National Geographic Society (2002). Field Guide to the Birds of North America. National Geographic, Washington DC. ISBN 0-7922-6877-6

External links

- American Bittern – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- American bittern – Botaurus lentiginosus – USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- American Bittern Botaurus lentiginosus – ENature.com

- "North American Bittern media". Internet Bird Collection.

- American Bittern photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)