Anfal campaign

The Anfal campaign[lower-alpha 1] or the Kurdish genocide was a counterinsurgency operation which was carried out by Ba'athist Iraq from February to September 1988, at the end of the Iran–Iraq War. The campaign targeted rural Kurds[1] because its purpose was to eliminate Kurdish rebel groups and Arabize strategic parts of the Kirkuk Governorate.[2]

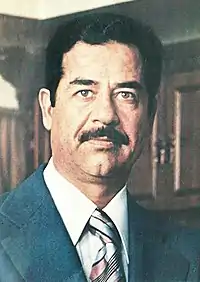

The Iraqi forces were led by Ali Hassan al-Majid, on the orders of President Saddam Hussein. The campaign's name was taken from the title of Qur'anic chapter 8 (al-ʾanfāl).

In 1993, Human Rights Watch released a report on the Anfal campaign based on documents captured by Kurdish rebels during the 1991 uprisings in Iraq; HRW described it as a genocide and estimated between 50,000 to 100,000 deaths. Although many Iraqi Arabs reject that there were any mass killings of Kurdish civilians during Anfal, the event is an important element constituting Kurdish national identity.

Background

Following the Iraqi invasion of Iran in 1980, the rival Kurdish opposition parties in Iraq—the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) and Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) as well as other smaller Kurdish parties—experienced a revival in their fortunes. Kurdish fighters (peshmerga) fought a guerrilla war against the Iraqi government and established effective control over the Kurdish-inhabited mountainous areas of northern Iraq. As the war went on and Iran counterattacked into Iraq, the peshmerga gained ground in most Kurdish-inhabited rural areas while also infiltrating towns and cities. In 1983, after the joint KDP-Iranian capture of Haj Omran, the Iraqi government arrested 8,000 Barzani men and executed them. During the battle for Haj Omran, the Iraqi government also used gas weapons for the first time against both Kurdish and Iranian forces.[3]

Name

"Al Anfal", literally meaning the spoils (of war),[4] was used to describe the military campaign of extermination and looting against the Kurds. It is also the title of the eighth sura, or chapter, of the Qur'an [4] which describes the victory of 313 followers of the new Muslim faith over almost 900 non-Muslims at the Battle of Badr in 624 AD. According to Randal, Jash (Kurdish collaborators with the Baathists) were told that taking cattle, sheep, goats, money, weapons and even women was halal (religiously permitted or legal).[5]

Summary

The Anfal campaign began in February 1988 and continued until August or September and included the use of ground offensives, aerial bombing, chemical warfare, systematic destruction of settlements, mass deportation and firing squads. The campaign was headed by Ali Hassan al-Majid (nicknamed "Chemical Ali" for the chemical attacks) who was a cousin of Iraqi President Saddam Hussein from Saddam's hometown of Tikrit.[6]

The Iraqi Army was supported by Kurdish collaborators whom the Iraqi government armed, the so-called Jash forces, who led Iraqi troops to Kurdish villages that often did not figure on maps as well as to their hideouts in the mountains. The Jash forces frequently made false promises of amnesty and safe passage.[7] Iraqi state media extensively covered the Anfal campaign using its official name.[6] To many Iraqis, Anfal was presented as an extension of the ongoing Iran–Iraq War, although its victims were overwhelmingly Kurdish civilians.[6]

Campaign

In March 1987, Ali Hassan al-Majid was appointed secretary-general of the Ba'ath Party's Northern Bureau,[8] which included Iraqi Kurdistan. Under al-Majid, control of policies against the Kurdish insurgents passed from the Iraqi Army to the Ba'ath Party.

Military operations and chemical attacks

Anfal, officially conducted in 1988, had eight stages (Anfal 1–Anfal 8) altogether, seven of which targeted areas controlled by the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan. The Kurdish Democratic Party-controlled areas in the northwest Iraqi Kurdistan, were the target of the Final Anfal operation in late August and early September 1988.

Anfal 1

The first Anfal stage was conducted between 23 February and 18 March 1988. It started with artillery and air strikes in the early hours of 23 February 1988. Then, several hours later, there were attacks at the Jafali Valley headquarters of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan near the Iranian border, and the command centers in Sargallu and Bargallu. There was heavy resistance by the Peshmerga. The battles were conducted in a theater around 1,154 square kilometres (445 sq. mi.).[9] The villages of Gwezeela, Chalawi, Haladin and Yakhsamar were attacked with poison gas. During mid March, the PUK, in an alliance with Iranian troops and other Kurdish factions, captured Halabja.[10] This led to the poison gas attack on Halabja on 16 March 1988,[10] during which 3,200–5,000 Kurdish people were killed, most of them civilians.[11][12]

Anfal 2

During the second Anfal from 22 March and 2 April 1988, the Qara Dagh region, including Bazian and Darbandikhan, was targeted in the Suleimanya governorate. Again several villages were attacked with poison gas. Villages attacked with poisonous gas were Safaran, Sewsenan, Belekjar, Serko and Meyoo. The attacks began on 22 March after Newruz, surprising the Peshmerga. Although of shorter duration, Peshmerga suffered more severe casualties in this attack than the first Anfal.[9] As a result of the attack, the majority of the population in the Qara Dagh region fled in direction Suleimanya. Many fugitives were detained by the Iraqi forces, and the men were separated from the women. The men were not seen again. The women were transported to camps. The population that managed to flee, fled to the Garmia region.[13]

Anfal 3

In the next Anfal campaign from 7 to 20 April 1988, the Garmian region east of Suleimanya was targeted. In this campaign, many women and children disappeared. The only village attacked with chemical weapons was Tazashar. Many were lured to come towards the Iraqi forces due to an amnesty announced through a loudspeaker of a mosque in Qader Karam from 10 to 12 April. The announced amnesty was a trap, and many who surrendered were detained. Some civilians were able to bribe Kurdish collaborators of the Iraqi Army and fled to Laylan or Shorsh.[14] Before the Anfal campaign, the mainly rural Garmian region counted over 600 villages around the towns of Kifri, Kalar and Darbandikhan.[15]

Anfal 4

Anfal 4 took place between 3–8 May 1988 in the valley of the Little Zab, which forms the border of the provinces of Erbil and Kirkuk. The morale of the Iraqi army was on the rise due to the capture of the Faw Peninsula on the 17–18 April 1988 from Iran in the Iran–Iraq War.[16] Major poisonous gas attacks were perpetrated in Askar and Goptapa.[17] Again it was announced an amnesty was issued, which turned out to be false. Many of the ones who surrendered were arrested. Men were separated from the women.[18]

Anfal 5, 6 and 7

In these three consecutive attacks between 15 May and 16 August 1988, the valleys of Rawandiz and Shaqlawa were targeted, and the attacks had different successes. The Anfal 5 failed completely; therefore, two more attacks were necessary to gain Iraqi government control over the valleys. The Peshmerga commander of the region, Kosrat Abdullah, was well prepared for a long siege with stores of ammunition and food. He also reached an agreement with the Kurdish collaborators of the Iraqi Army so that the civilians could flee. Hiran, Balisan, Smaquli, Malakan, Shek Wasan, Ware, Seran and Kaniba were attacked with poisonous gas. After the Anfal 7 attack, the valleys were under the control of the Iraqi government.[18]

Anfal 8

The last Anfal was aimed at the region controlled by the KDP named Badinan and took place from 25 August to 6 September 1988. In this campaign, the villages of Wirmeli, Barkavreh, Bilejane, Glenaska, Zewa Shkan, Tuka and Ikmala were targeted with chemical attacks. After tens of thousands of Kurds fled to Turkey, the Iraqi Army blocked the route to Turkey on 26 August 1988. The population who did not manage to flee was arrested, and the men were separated from the women and children. The men were executed, and the women and children were brought to camps.[19]

Detention camps

Detention camps were established to accommodate thousands of prisoners. Dibs was a detention camp for women and children and located near an army training facility for the Iraqi commando forces.[20] From Dibs, groups of detainees were transferred to Nugra Salman[21] in a depression in the desert about 120 Km southwest of Samawah,[22] in the Muthanna Governorate. Nugra Salman held an estimated 5'000 to 8'000 prisoners during the Anfal campaign.[21] Another detention camp was Topzawa near an army base near the highway leading out of Kirkuk.[23]

Arabisation

"Arabisation," another major element of al-Anfal, was a tactic used by Saddam Hussein's regime to drive pro-insurgent populations out of their homes in villages and cities like Kirkuk, which are in the valuable oil field areas, and relocate them in the southern parts of Iraq.[24] The campaign used heavy population redistribution, most notably in Kirkuk, the results of which now plague negotiations between Iraq's Shi'a United Iraqi Alliance and the Kurdish Kurdistani Alliance. Saddam's Ba'athist regime built several public housing facilities in Kirkuk as part of his "Arabisation," shifting poor Arabs from Iraq's southern regions to Kirkuk with the lure of inexpensive housing. Another part of the Arabisation campaign was the census of October 1987. Citizens who failed to turn up for the October 1987 census were no longer recognized as Iraqi citizens. Most of the Kurdish population who learned that a census was taking place did not take part in the census.[8]

Death toll

Precise figures of Anfal victims do not exist due to lack of records.[1] In its 1993 report, Human Rights Watch wrote that the death toll "cannot conceivably be less than 50,000, and it may well be twice that number".[25][1] This figure was based on an earlier survey by the Sulaymaniyah–based Kurdish organization Committee for the Defence of Anfal Victims' Rights.[1] According to HRW, Kurdish leaders met with Iraqi government official Ali Hassan al-Majid in 1991 and mentioned a figure of 182,000 deaths; the latter reportedly replied that "it couldn't have been more than 100,000".[25][1] The 182,000 figure provided by the PUK was based on extrapolation[6] and "has no empirical relation to actual disappearances or killings".[1] In 1995, the Committee for the Defence of Anfal Victims' Rights released a report documenting 63,000 disappeared and stating that the entire death toll was lower than 70,000, with almost all these deaths occurring in the area of Anfal III.[1] According to Hiltermann, the figure of 100,000, although considered too low by many Kurds, is probably higher than the actual number of deaths.[1]

Aftermath

In September 1988, the Iraqi government was satisfied with its achievements. The male population between 15 and 50 had either been killed or fled. The Kurdish resistance fled to Iran and was no longer a threat to Iraq. An amnesty was issued, and the detained women, children and elderly were released[26] but not permitted to return.[27] They were sent into camps known as mujamm'at where they lived under military rule until a regional autonomy for Iraqi Kurdistan was achieved in 1991.[27] Following, most survivors returned, and began to reconstruct the villages.[27] In Kurdish society, the Anfal survivors are known as Anfal mothers (Kurdish: Daykan-î Enfal), Anfal relatives (Kurdish: Kes-u-kar-î Enfal) or Anfal women without men (Kurdish: Bewajin-î Enfal).[27]

Trials

Human Rights Watch unsuccessfully attempted to attract support for a lawsuit under the Genocide Convention against Iraq at the International Court of Justice. It convinced the United States Department of State's legal bureau that Anfal met the legal criteria for genocide.[28]

Frans van Anraat

In December 2005, a court in The Hague convicted Frans van Anraat of complicity in war crimes for his role in selling chemical weapons to the Iraqi government. He was given a 15-year sentence.[29] The court also ruled that the killing of thousands of Kurds in Iraq in the 1980s was indeed an act of genocide.[29] In the 1948 Genocide Convention, the definition of genocide is "acts committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group". The Dutch court said that it was considered "legally and convincingly proven that the Kurdish population meets the requirement under the Genocide Conventions as an ethnic group. The court has no other conclusion than that these attacks were committed with the intent to destroy the Kurdish population of Iraq".[29]

Saddam Hussein

In an interview broadcast on Iraqi television on 6 September 2005, Iraqi President Jalal Talabani, a respected Kurdish politician, said that judges had directly extracted confessions from Saddam Hussein that he had ordered mass killings and other crimes during his regime and that he deserves to die. Two days later, Saddam's lawyer denied that he had confessed.[30]

Anfal trial

In June 2006, the Iraqi Special Tribunal announced that Saddam Hussein and six co-defendants would face trial on 21 August 2006 in relation to the Anfal campaign.[31] In December 2006, Saddam was put on trial for the genocide during Operation Anfal. The trial for the Anfal campaign was still underway on 30 December 2006, when Saddam Hussein was executed for his role in the unrelated Dujail massacre.[32]

The Anfal trial recessed on 21 December 2006, and when it resumed on 8 January 2007, the remaining charges against Saddam Hussein were dropped. Six co-defendants continued to stand trial for their roles in the Anfal campaign. On 23 June 2007, Ali Hassan al-Majid, and two co-defendants, Sultan Hashem Ahmed and Hussein Rashid Mohammed, were convicted of genocide and related charges and sentenced to death by hanging.[33] Another two co-defendants (Farhan Jubouri and Saber Abdel Aziz al-Douri) were sentenced to life imprisonment, and one (Taher Tawfiq al-Ani) was acquitted on the prosecution's demand.[34]

Al-Majid was charged with war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide. He was convicted in June 2007 and was sentenced to death. His appeal for the death sentence was rejected on 4 September, 2007. He was sentenced to death for the fourth time on 17 January 2010 and was hanged eight days later, on 25 January 2010.[35] Sultan Hashem Ahmed was not hanged due to opposition of the Iraqi President Jalal Talabani, who opposed the death penalty.[36]

Sources

There have been few publications about the Anfal campaign and as of 2008, the only comprehensive account of it is that which was published by HRW.[37] Human Rights Watch's 1993 report on Anfal was based on Iraqi documents, examination of grave sites, and interviews with Kurdish survivors.[38]

In 1993, the United States government collected 18 tons of Iraqi government documents which were captured by the Peshmerga during the 1991 uprising and airlifted them to the United States.[39] In those files, HRW conducted research on the Anfal campaign in collaboration with United States federal government agencies such as the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), the Defense Intelligence Agency, and the Defense Department.[39] The US government provided Arabic translators and CD ROM scanners.[39] HRW accepted the US government role under the condition that personnel involved worked under its direction.[39] The files include documents which were collected by the Kurdish parties PUK and KDP, both parties hold the ultimate ownership of the documents that were airlifted to the US.[39]

In exchange for access to the National Archives documents, HRW agreed to help the United States government find information about Iraqi atrocities. Joost Hiltermann, HRW's lead researcher on Anfal, referred to these files as "the good stuff…material to smear the enemy with".[40] Kanan Makiya, an Iraqi–American academic and pro-Iraq War advocate,[41] criticized HRW for promising that the records proved genocide. He warned that the records contained neither "smoking guns" nor do they contain records of the "explosive nature" as HRW claimed. Furthermore, he said that certain documents that seemed incriminating could have been planted by Kurdish rebels.[40] After the invasion of Iraq, Makiya said in December 2003 that the Iraqi document archives contained no "smoking gun" to convict Saddam Hussein of war crimes.[42]

After the United States invasion of Iraq in 2003, mass graves were discovered in parts of western Iraq that had been under Ba'athist control.[1]

Legacy

The event has become an important element in the constitution of Kurdish national identity.[43] The Kurdistan Regional Government has set aside 14 April as a day of remembrance for the Al-Anfal campaign.[44] In Sulaymanya a museum was established in the former prison of the Directorate of General Security.[45] Many Iraqi Arabs reject that any mass killings of Kurds occurred during the Anfal campaign.[28]

On 28 February 2013, the British House of Commons formally recognized the Anfal as genocide following a campaign which was led by Conservative MP Nadhim Zahawi, who is of Kurdish descent.[46]

References

- Hiltermann 2008, Victims.

- Kirmanj & Rafaat 2021, p. 163.

- Hiltermann 2008, Context.

- Montgomery 2001, p. 70.

- Randal, Jonathan C. (4 March 2019). After Such Knowledge, What Forgiveness?: My Encounters With Kurdistan. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-71113-8.

- Makiya, Kanan (1994). Cruelty and Silence: War, Tyranny, Uprising, and the Arab World. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 163–168. ISBN 9780393311419.

- Hardi 2011, p. 17.

- Hardi 2011, pp. 16–17.

- Nation Building in Kurdistan: Memory, Genocide and Human Rights

- Hardi 2011, p. 19.

- "BBC on this day: Thousands die in Halabja gas attack". BBC News. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- Beeston, Richard (18 January 2010). "Halabja, the massacre the West tried to ignore". The Times. Archived from the original on 23 January 2010. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- Hardi 2011, pp. 19–20.

- Hardi 2011, p. 20.

- Mlodoch, Karin. The limits of Trauma discourse, Women Anfal survivors in Kurdistan-Iraq. Berlin: Zentrum Moderner Orient, Klaus Schwarz Verlag. p. 167.

- Black 1993, pp. 171–172.

- Black 1993, pp. 172–176.

- Hardi 2011, p. 21.

- Hardi 2011, pp. 21–22.

- Black, George, (1993), pp. 222–223

- Black, George; Staff, Middle East Watch; Watch (Organization), Middle East (1993). Genocide in Iraq: The Anfal Campaign Against the Kurds. Human Rights Watch. p. 226. ISBN 978-1-56432-108-4.

- Sissakian, Varoujan K. (January 2020). "Origins and Utilizations of the Main Natural Depressions in Iraq". ResearchGate. p. 23–24.

- Black, George, (1993), p.209

- Black 1993, p. 36.

- Black 1993, p. 345.

- Hardi 2011, p. 22.

- Mlodoch, Karin (2012). ""We Want to be Remembered as Strong Women, Not as Shepherds": Women Anfal Survivors in Kurdistan-Iraq Struggling for Agency and Acknowledgement". Journal of Middle East Women's Studies. 8 (1): 65. doi:10.2979/jmiddeastwomstud.8.1.63. ISSN 1552-5864. JSTOR 10.2979/jmiddeastwomstud.8.1.63. S2CID 145055297 – via JSTOR.

- Hiltermann 2008, Interpretation of facts.

- "Killing of Iraq Kurds 'genocide'". BBC. 23 December 2005. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- Lawyer denies Saddam confession BBC News, 8 September 2005

- Iraqi High Tribunal announces second Saddam trial to open Associated Press, 27 June 2006

- Dictator Who Ruled Iraq With Violence Is Hanged for Crimes Against Humanity The New York Times, 30 December 2006

- Omar Sinan (25 June 2007). "Iraq to hang 'Chemical Ali'". Tampa Bay Times. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- 'Chemical Ali' sentenced to hang CNN, 24 June 2007

- "Saddam Hussein's henchman 'Chemical Ali' executed". The Daily Telegraph. 25 January 2010. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- "Iraqi president opposes minister's hanging". The Irish Times. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- Hiltermann 2008, Bibliography.

- Black 1993, p. 28.

- Montgomery 2001, pp. 78–79.

- Alshaibi, Wisam. "Weaponizing Iraq's Archives". Middle East Report (291 (Summer 2019) ed.).

- Beaumont, Peter (25 March 2007). "We failed, says pro-war Iraqi". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- Pelletiere 2016, p. 62.

- Cockrell-Abdullah 2018, p. 70.

- "Anfal campaign receives national day of remembrance". Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- Majid, Bareez. "The Museum of Amna Suraka: a Critical Case Study of Kurdistani Memory Culture". Leiden University. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- "Historic Debate Secures Parliamentary Recognition of the Kurdish Genocide". Huffington Post. March 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

Sources

- Black, George (1993). Genocide in Iraq: The Anfal Campaign Against the Kurds. Human Rights Watch. ISBN 978-1-56432-108-4.

- Cockrell-Abdullah, Autumn (2018). "Constituting Histories Through Culture In Iraqi Kurdistan". Zanj: The Journal of Critical Global South Studies. 2 (1): 65–91. doi:10.13169/zanjglobsoutstud.2.1.0065. ISSN 2515-2130. JSTOR 10.13169/zanjglobsoutstud.2.1.0065.

- Hardi, Choman (2011). Gendered Experiences of Genocide: Anfal Survivors in Kurdistan-Iraq. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4094-9008-1.

- Hiltermann, Joost (2008). "The 1988 Anfal Campaign in Iraqi Kurdistan". Mass Violence & Resistance. Sciences Po. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- Kirmanj, Sherko; Rafaat, Aram (2021). "The Kurdish genocide in Iraq: the Security-Anfal and the Identity-Anfal". National Identities. 23 (2): 163–183. doi:10.1080/14608944.2020.1746250.

- Montgomery, Bruce P. (2001). "The Iraqi Secret Police Files: A Documentary Record of the Anfal Genocide". Archivaria: 69–99. ISSN 1923-6409.

- Pelletiere, Stephen (2016). Oil and the Kurdish Question: How Democracies Go to War in the Era of Late Capitalism. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-1-4985-1666-2.

Further reading

- Baser, Bahar; Toivanen, Mari (2017). "The politics of genocide recognition: Kurdish nation-building and commemoration in the post-Saddam era". Journal of Genocide Research. 19 (3): 404–426. doi:10.1080/14623528.2017.1338644. hdl:10138/325889. S2CID 58142027.

- Donabed, Sargon (2015). Reforging a Forgotten History: Iraq and the Assyrians in the Twentieth Century. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-8603-2.

- Fischer-Tahir, Andrea (2012). "Gendered Memories and Masculinities: Kurdish Peshmerga on the Anfal Campaign in Iraq". Journal of Middle East Women's Studies. 8 (1): 92–114. doi:10.2979/jmiddeastwomstud.8.1.92. S2CID 143526869.

- Hamarafiq, Rebeen (2019). "Cultural Responses to the Anfal and Halabja Massacres". Genocide Studies International. 13 (1): 132–142. doi:10.3138/gsi.13.1.07. S2CID 208688723.

- Leurs, Rob (2011). "Reliving genocide: the work of Kurdish genocide victims in the Court of Justice". Critical Arts. 25 (2): 296–303. doi:10.1080/02560046.2011.569081. S2CID 143839339.

- Mlodoch, Karin (2021). The Limits of Trauma Discourse: Women Anfal Survivors in Kurdistan-Iraq. de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-240283-2.

- Muhammad, Kurdistan Omar; Hama, Hawre Hasan; Hama Karim, Hersh Abdallah (2022). "Memory and trauma in the Kurdistan genocide". Ethnicities: 146879682211032. doi:10.1177/14687968221103254. S2CID 248910712.

- Sadiq, Ibrahim (2021). Origins of the Kurdish Genocide: Nation Building and Genocide as a Civilizing and De-Civilizing Process. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-7936-3683-6.

- Szanto, Edith (2018). "Mourning Halabja on Screen: Or Reading Kurdish Politics through Anfal Films". Review of Middle East Studies. 52 (1): 135–146. doi:10.1017/rms.2018.3. S2CID 158673771.

- Toivanen, Mari; Baser, Bahar (2019). "Remembering the Past in Diasporic Spaces: Kurdish Reflections on Genocide Memorialization for Anfal". Genocide Studies International. 13 (1): 10–33. doi:10.3138/gsi.13.1.02. hdl:10138/321880. S2CID 166812947.

- Trahan, Jennifer (2008–2009). "A Critical Guide to the Iraqi High Tribunal's ANFAL Judgment: Genocide against the Kurds". Michigan Journal of International Law. 30: 305.