Antoni Gaudí

Antoni Gaudí i Cornet (/ˈɡaʊdi/; Catalan: [ənˈtɔni ɣəwˈði]; 25 June 1852 – 10 June 1926) was a Catalan architect from Spain known as the greatest exponent of Catalan Modernism.[3] Gaudí's works have a highly individualized, sui generis style. Most are located in Barcelona, including his main work, the church of the Sagrada Família.

Antoni Gaudí Cornet | |

|---|---|

Gaudí in 1878, by Pau Audouard | |

| Born | 25 June 1852 |

| Died | 10 June 1926 (aged 73) Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Buildings |

|

| Projects |

|

| Website | www www casabatllo |

Gaudí's work was influenced by his passions in life: architecture, nature, and religion.[4] He considered every detail of his creations and integrated into his architecture such crafts as ceramics, stained glass, wrought ironwork forging and carpentry. He also introduced new techniques in the treatment of materials, such as trencadís which used waste ceramic pieces.

Under the influence of neo-Gothic art and Oriental techniques, Gaudí became part of the Modernista movement which was reaching its peak in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His work transcended mainstream Modernisme, culminating in an organic style inspired by natural forms. Gaudí rarely drew detailed plans of his works, instead preferring to create them as three-dimensional scale models and moulding the details as he conceived them.

Gaudí's work enjoys global popularity and continuing admiration and study by architects. His masterpiece, the still-incomplete Sagrada Família, is the most-visited monument in Spain.[5] Between 1984 and 2005, seven of his works were declared World Heritage Sites by UNESCO. Gaudí's Roman Catholic faith intensified during his life and religious images appear in many of his works. This earned him the nickname "God's Architect"[6] and led to calls for his beatification.[6][7]

Biography

Birth, childhood, and studies

Gaudí was born on 25 June 1852 in Riudoms or Reus,[8] to the coppersmith Francesc Gaudí i Serra (1813–1906)[9] and Antònia Cornet i Bertran (1819–1876). He was the youngest of five children, of whom three survived to adulthood: Rosa (1844–1879), Francesc (1851–1876) and Antoni. Gaudí's family originated in the Auvergne region in southern France. One of his ancestors, Joan Gaudí, a hawker, moved to Catalonia in the 17th century; possible origins of Gaudí's family name include Gaudy or Gaudin.[10]

Gaudí's exact birthplace is unknown because no supporting documents have been found, leading to a controversy about whether he was born in Reus or Riudoms, two neighbouring municipalities of the Baix Camp district. Most of Gaudí's identification documents from both his student and professional years gave Reus as his birthplace. Gaudí stated on various occasions that he was born in Riudoms, his paternal family's village.[11] Gaudí was baptised in the church of Sant Pere Apòstol in Reus the day after his birth under the name "Antoni Plàcid Guillem Gaudí i Cornet".[12]

Gaudí had a deep appreciation for his native land and great pride in his Mediterranean heritage for his art. He believed Mediterranean people to be endowed with creativity, originality and an innate sense for art and design. Gaudí reportedly described this distinction by stating, "We own the image. Fantasy comes from the ghosts. Fantasy is what people in the North own. We are concrete. The image comes from the Mediterranean. Orestes knows his way, where Hamlet is torn apart by his doubts."[13] Time spent outdoors, particularly during summer stays in the Gaudí family home Mas de la Calderera, afforded Gaudí the opportunity to study nature. Gaudí's enjoyment of the natural world led him to join the Centre Excursionista de Catalunya in 1879 at the age of 27. The organisation arranged expeditions to explore Catalonia and southern France, often riding on horseback or walking ten kilometres a day.[14]

.jpg.webp)

Young Gaudí suffered from poor health, including rheumatism, which may have contributed to his reticent and reserved character.[15] These health concerns and the hygienist theories of Dr. Kneipp[16] contributed to Gaudí's decision to adopt vegetarianism early in his life.[17][18] His religious faith and strict vegetarianism led him to undertake several lengthy and severe fasts. These fasts were often unhealthy and occasionally, as in 1894, led to life-threatening illness.[19]

Gaudí attended a nursery school run by Francesc Berenguer, whose son, also called Francesc, was later one of Gaudí's main assistants. He enrolled in the Piarists school in Reus where he displayed his artistic talents via drawings for a seminar called El Arlequín (the Harlequin).[20] During this time, he worked as an apprentice in the "Vapor Nou" textile mill in Reus. In 1868, he moved to Barcelona to study teaching in the Convent del Carme. In his adolescent years, Gaudí became interested in utopian socialism and, together with his fellow students Eduard Toda i Güell and Josep Ribera i Sans, planned a restoration of the Poblet Monastery that would have transformed it into a Utopian phalanstère.[21]

Between 1875 and 1878, Gaudí completed his compulsory military service in the infantry regiment in Barcelona as a Military Administrator. Most of his service was spent on sick leave, enabling him to continue his studies. His poor health kept him from having to fight in the Third Carlist War, which lasted from 1872 to 1876.[22] In 1876, Gaudí's mother died at the age of 57, as did his 25-year-old brother Francesc, who had just graduated as a physician. During this time Gaudí studied architecture at the Llotja School and the Barcelona Higher School of Architecture, graduating in 1878. To finance his studies, Gaudí worked as a draughtsman for various architects and constructors such as Leandre Serrallach, Joan Martorell, Emili Sala Cortés, Francisco de Paula del Villar y Lozano and Josep Fontserè.[23] In addition to his architecture classes, he studied French, history, economics, philosophy, and aesthetics. His grades were average and he occasionally failed courses.[24] When handing him his degree, Elies Rogent, director of Barcelona Architecture School, said: "We have given this academic title either to a fool or a genius. Time will show."[25] Gaudí, when receiving his degree, reportedly told his friend, the sculptor Llorenç Matamala, with his ironical sense of humour, "Llorenç, they're saying I'm an architect now."[26]

Adulthood and professional work

.jpg.webp)

Gaudí's first projects were the lampposts he designed for the Plaça Reial in Barcelona, the unfinished Girossi newsstands, and the Cooperativa Obrera Mataronense (Workers' Cooperative of Mataró) building. He gained wider recognition for his first important commission, the Casa Vicens, and subsequently received more significant proposals. At the Paris World's Fair of 1878 Gaudí displayed a showcase he had produced for the glove manufacturer Comella. Its functional and aesthetic modernista design impressed Catalan industrialist Eusebi Güell, who then commissioned some of Gaudí's most outstanding work: the Güell wine cellars, the Güell pavilions, the Palau Güell (Güell palace), the Park Güell (Güell park) and the crypt of the church of the Colònia Güell. Gaudí also became a friend of the marquis of Comillas, the father-in-law of Count Güell, for whom he designed "El Capricho" in Comillas.

In 1883 Gaudí was put in charge of the recently initiated project to build a Barcelona church called Basílica i Temple Expiatori de la Sagrada Família (Basilica and Expiatory Church of the Holy Family, or Sagrada Família). Gaudí completely changed the initial design and imbued it with his own distinctive style. From 1915 until his death he devoted himself entirely to this project. Given the number of commissions he began receiving, he had to rely on his team to work on multiple projects simultaneously. His team consisted of professionals from all fields of construction. Several of the architects who worked under him became prominent in the field later on, such as Josep Maria Jujol, Joan Rubió, Cèsar Martinell, Francesc Folguera and Josep Francesc Ràfols. In 1885, Gaudí moved to rural Sant Feliu de Codines to escape the cholera epidemic that was ravaging Barcelona. He lived in Francesc Ullar's house, for whom he designed a dinner table as a sign of his gratitude.[27]

.jpg.webp)

The 1888 World Fair was one of the era's major events in Barcelona and represented a key point in the history of the Modernisme movement. Leading architects displayed their best works, including Gaudí, who showcased the building he had designed for the Compañía Trasatlántica (Transatlantic Company). Consequently, he received a commission to restructure the Saló de Cent of the Barcelona City Council, but this project was ultimately not carried out. In the early 1890s Gaudí received two commissions from outside of Catalonia, namely the Episcopal Palace, Astorga, and the Casa Botines in León. These works contributed to Gaudí's growing renown across Spain. In 1891, he travelled to Málaga and Tangiers to examine the site for a project for the Franciscan Catholic Missions that the 2nd marquis of Comillas had requested him to design.[28]

In 1899 Gaudí joined the Cercle Artístic de Sant Lluc (Saint Luke artistic circle), a Catholic artistic society founded in 1893 by the bishop Josep Torras i Bages and the brothers Josep and Joan Llimona. He also joined the Lliga Espiritual de la Mare de Déu de Montserrat (spiritual league of Our lady of Montserrat), another Catholic Catalan organisation.[29] The conservative and religious character of his political thought was closely linked to his defence of the cultural identity of the Catalan people.[30]

At the beginning of the century, Gaudí was working on numerous projects simultaneously. They reflected his shift to a more personal style inspired by nature. In 1900, he received an award for the best building of the year from the Barcelona City Council for his Casa Calvet. During the first decade of the century Gaudí dedicated himself to projects like the Casa Figueras (Figueras house, better known as Bellesguard), the Park Güell, an unsuccessful urbanisation project, and the restoration of the Cathedral of Palma de Mallorca, for which he visited Majorca several times. Between 1904 and 1910 he constructed the Casa Batlló (Batlló house) and the Casa Milà (Milá house), two of his most emblematic works.

As a result of Gaudí's increasing fame, in 1902 the painter Joan Llimona chose Gaudí's features to represent Saint Philip Neri in the paintings for the aisle of the Sant Felip Neri church in Barcelona.[31] Together with Joan Santaló, son of his friend the physician Pere Santaló, he unsuccessfully founded a wrought iron manufacturing company the same year.[32]

After moving to Barcelona, Gaudí frequently changed his address: as a student he lived in residences, generally in the area of the Gothic Quarter; when he started his career he moved around several rented flats in the Eixample area. Finally, in 1906, he settled in a house in the Güell Park that he owned and which had been constructed by his assistant Francesc Berenguer as a showcase property for the estate. It has since been transformed into the Gaudí Museum. There he lived with his father (who died in 1906 at the age of 93) and his niece Rosa Egea Gaudí (who died in 1912 at the age of 36). He lived in the house until 1925, several months before his death, when he began residing inside the workshop of the Sagrada Família.

An event that had a profound impact on Gaudí's personality was Tragic Week in 1909. Gaudí remained in his house in Güell Park during this turbulent period. The anticlerical atmosphere and attacks on churches and convents caused Gaudí to worry for the safety of the Sagrada Família, but the building escaped damage.[33]

In 1910, an exhibition in the Grand Palais of Paris was devoted to his work, during the annual salon of the Société des Beaux-Arts (Fine Arts Society) of France. Gaudí participated on the invitation of count Güell, displaying a series of pictures, plans and plaster scale models of several of his works. Although he participated hors concours, he received good reviews from the French press. A large part of this exposition could be seen the following year at the I Salón Nacional de Arquitectura that took place in the municipal exhibition hall of El Buen Retiro in Madrid.[34]

During the Paris exposition in May 1910, Gaudí spent a holiday in Vic, where he designed two basalt lampposts and wrought iron for the Plaça Major of Vic in honor of Jaume Balmes's centenary. The following year he resided as a convalescent in Puigcerdà while suffering from tuberculosis. During this time he conceived the idea for the façade of the Passion of the Sagrada Família.[35] Due to ill health he prepared a will at the office of the notary Ramon Cantó i Figueres on 9 June, but later completely recovered.[36]

The decade from 1910 was a hard one for Gaudí. During this decade, the architect experienced the deaths of his niece Rosa in 1912 and his main collaborator Francesc Berenguer in 1914; a severe economic crisis which paralysed work on the Sagrada Família in 1915; the 1916 death of his friend Josep Torras i Bages, bishop of Vic; the 1917 disruption of work at the Colonia Güell; and the 1918 death of his friend and patron Eusebi Güell.[37] Perhaps because of these tragedies he devoted himself entirely to the Sagrada Família from 1915, taking refuge in his work. Gaudí confessed to his collaborators:

My good friends are dead; I have no family and no clients, no fortune nor anything. Now I can dedicate myself entirely to the Church.[38]

Gaudí dedicated the last years of his life entirely to the "Cathedral of the Poor", as it was commonly known, for which he took alms in order to continue. Apart from his dedication to this cause, he participated in few other activities, the majority of which were related to his Catholic faith: in 1916 he participated in a course about Gregorian chant at the Palau de la Música Catalana taught by the Benedictine monk Gregori M. Sunyol.[39]

In 1936, during the course of the Spanish Civil War, Gaudí's workshop in the Sagrada Familia was assaulted, destroying a large number of documents, plans and models of the modernist architect.

Personal life

Gaudí devoted his life entirely to his profession, remaining single. He is known to have been attracted to only one woman—Josefa Moreu, teacher at the Mataró Cooperative, in 1884—but this was not reciprocated.[40] Thereafter Gaudí took refuge in the profound spiritual peace his Catholic faith offered him. Gaudí is often depicted as unsociable and unpleasant, a man of gruff reactions and arrogant gestures. However, those who were close to him described him as friendly and polite, pleasant to talk to and faithful to friends. Among these, his patrons Eusebi Güell and the bishop of Vic, Josep Torras i Bages, stand out, as well as the writers Joan Maragall and Jacint Verdaguer, the physician Pere Santaló and some of his most faithful collaborators, such as Francesc Berenguer and Llorenç Matamala.[41]

.jpg.webp)

Gaudí's personal appearance—Nordic features, blond hair and blue eyes—changed radically over the course of time. As a young man, he dressed like a dandy in costly suits, sporting well-groomed hair and beard, indulging gourmet taste, making frequent visits to the theatre and the opera and visiting his project sites in a horse carriage. The older Gaudí ate frugally, dressed in old, worn-out suits, and neglected his appearance to the extent that sometimes he was taken for a beggar, such as after the accident that caused his death.[44]

Gaudí left hardly any written documents, apart from technical reports of his works required by official authorities, some letters to friends (particularly to Joan Maragall) and a few journal articles. Some quotes collected by his assistants and disciples have been preserved, above all by Josep Francesc Ràfols, Joan Bergós, Cèsar Martinell and Isidre Puig i Boada. The only written document Gaudí left is known as the Manuscrito de Reus (Reus Manuscript) (1873–1878), a kind of student diary in which he collected diverse impressions of architecture and decorating, putting forward his ideas on the subject. Included are an analysis of the Christian church and of his ancestral home, as well as a text about ornamentation and comments on the design of a desk.[45]

Catalan identity

Gaudí was a committed Catalan nationalist and proponent of Catalan culture but was reluctant to become politically active to campaign for its autonomy.[46][47][48][49] Politicians, such as Francesc Cambó and Enric Prat de la Riba, suggested that he run for deputy but he refused.[48] Compared to some of his colleagues and contemporaries, his Catalan nationalism was less political and more geared towards art, history, culture, and language.[48][49]

Gaudí has a deep attachment to his native Catalan language.[50][47][51] When King of Spain Alfonso XIII visited the Sagrada Familia, Gaudí declined to speak in Spanish and only spoke to him in Catalan.[47][52] Gaudí also refused to speak Spanish with Prime Minister Antonio Maura, who, being a native of Mallorca and therefore Catalan-speaking, ended up responding to Gaudí in Catalan, thus breaking protocol in front of the King Alfonso XIII.[53] Similarly, when philosopher Miguel de Unamuno visited the Sagrada Família, poet Joan Maragall had to translate Gaudí's Catalan tour into Spanish.[54][55] Gaudí also spoke Catalan in public, despite it being declared illegal by the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera, which severely tried to suppress Catalan culture.[56][57]

_-_7.jpg.webp)

In 1920 he was beaten by police in a riot during the Floral Games celebrations, a Catalan culture celebration.[58][47] On 11 September 1924, National Day of Catalonia, he was beaten at a demonstration against the banning of the Catalan language by the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera. Gaudí was arrested by the Civil Guard as he was headed to the church of Sant Just i Sant Pastor to attend a mass in memory of the Catalonian patriots. Gaudí refused to speak Castilian Spanish and kept responding in Catalan, stating that "My profession obliges me to pay my taxes, and I pay them, but not to stop speaking my own language."[47][59][60][61][62] He was then taken to prison, from which he was freed after paying 50 pesetas bail.[63]

Gaudí incorporated elements of Catalan culture and identity in his works. Gaudí was part of the Catalan Renaissance (Renaixença in Catalan), romantic revivalist and cultural movement that aimed at restoring Catalan language and arts combined with an anti-Castilian political "Catalanism."[64][51] Park Güell, which was commissioned by Catalan patriot Eusebi Güell, was envisioned by Gaudí as a focus of Catalan nationalism and cultural aspirations.[65][66][67][51] Gaudí inserted numerous motifs from Catalan culture in the park, such as a large mosaic with the Catalan flag or the representations of dragons, which were seen as Catalan symbols during the Renaixença because of their connection to the Catalan patron saint George.[68][66][69] The Park was also host to the First Congress of the Catalan Language while it was still under construction.[66] Casa Batlló, which is considered among Gaudí's finest examples of Catalan Modernism, is known as "the House of the Dragon" due to its symbolism related to the legend of Saint George, the patron saint of Catalonia.[70][71] The Sagrada Familia is decorated with many words and writings, such as on the towers and doors, and are mainly in Catalan, such as the Lord's Prayer in Catalan on the main doors.[72] The Palau Güell's entrance is decorated with the Catalan coat of arms and a helmet with a winged dragon.[73] His project for Barcelona's Muralla de Mar featured shields and names of battles and Catalan admirals.[74] The Torre Bellesguard (1900–1909), former summer palace of King Martin I the Humane, was restored by Gaudí and its spire decorated the Catalan flag and the royal crown.[75][76] He also designed a project (never terminated) to crown El Cavall Bernat (a mountain peak) with a viewpoint in the shape of a royal crown and a 20 meters (66 ft) high Catalan coat of arms.[77] The Catalan flag was also present in a banner designed for Our Lady of Mercy of Reus and a monument (not completed) to Catalan politician Enric Prat de la Riba in Castellterçol. Even before he became an architect, he was very interested in the history of medieval Catalonia, when it was a big player in Mediterranean politics and history.[49] He joined several Catalan associations, such as Cercle Artístic de Sant Lluc, Lliga Espiritual de la Mare de Déu de Montserrat, Associació Catalanista d'Excursions Científiques.[78][51][49] The latter was a group dedicated to preserve and celebrate the art, landscape, culture, and language of Catalunya.

Death

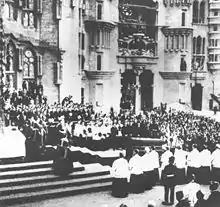

On 7 June 1926, Gaudí was taking his daily walk to the Sant Felip Neri church for his habitual prayer and confession. While walking along the Gran Via de les Corts Catalanes between Girona and Bailén streets, he was struck by a passing number 30 tram and lost consciousness.[79][80] Assumed to be a beggar, the unconscious Gaudí did not receive immediate aid. Eventually some passers-by transported him in a taxi to the Santa Creu Hospital, where he received rudimentary care.[81]

By the time that the chaplain of the Sagrada Família, Mosén Gil Parés, recognised him on the following day, Gaudí's condition had deteriorated too severely to benefit from additional treatment. Gaudí died on 10 June 1926 at the age of 73 and was buried two days later. A large crowd gathered to bid farewell to him in the chapel of Our Lady of Mount Carmel in the crypt of the Sagrada Família. His gravestone bears this inscription:

Antonius Gaudí Cornet. Reusensis. Annos natus LXXIV, vitae exemplaris vir, eximiusque artifex, mirabilis operis hujus, templi auctor, pie obiit Barcinone die X Junii MCMXXVI, hinc cineres tanti hominis, resurrectionem mortuorum expectant. R.I.P.[82]

(Antoni Gaudí Cornet. From Reus. At the age of 74, a man of exemplary life, and an extraordinary craftsman, the author of this marvelous work, the church, died piously in Barcelona on the tenth day of June 1926; henceforward the ashes of so great a man await the resurrection of the dead. May he rest in peace.)

Style

Gaudí and Modernisme

Gaudí's professional life was distinctive in that he never ceased to investigate mechanical building structures. Early on, Gaudí was inspired by oriental arts (India, Persia, Japan) through the study of the historicist architectural theoreticians, such as Walter Pater, John Ruskin and William Morris. The influence of the Oriental movement can be seen in works like the Capricho, the Güell Palace, the Güell Pavilions and the Casa Vicens. Later on, he adhered to the neo-Gothic movement that was in fashion at the time, following the ideas of the French architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. This influence is reflected in the Teresian College, the Episcopal Palace in Astorga, the Casa Botines and the Bellesguard house as well as in the crypt and the apse of the Sagrada Família. Eventually, Gaudí embarked on a more personal phase, with the organic style inspired by nature in which he would build his major works.

During his time as a student, Gaudí was able to study a collection of photographs of Egyptian, Indian, Persian, Mayan, Chinese and Japanese art owned by the School of Architecture. The collection also included Moorish monuments in Spain, which left a deep mark on him and served as an inspiration in many of his works. He also studied the book Plans, elevations, sections and details of the Alhambra by Owen Jones, which he borrowed from the School's library.[83] He took various structural and ornamental solutions from Nasrid and Mudéjar art, which he used with variations and stylistic freedom in his works. Notably, Gaudí observed of Islamic art its spatial uncertainty, its concept of structures with limitless space; its feeling of sequence, fragmented with holes and partitions, which create a divide without disrupting the feeling of open space by enclosing it with barriers.[84]

Undoubtedly the style that most influenced him was the Gothic Revival, promoted in the latter half of the 19th century by the theoretical works of Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. The French architect called for studying the styles of the past and adapting them in a rational manner, taking into account both structure and design.[85] Nonetheless, for Gaudí the Gothic style was "imperfect", because despite the effectiveness of some of its structural solutions it was an art that had yet to be "perfected". In his own words:

Gothic art is imperfect, only half resolved; it is a style created by the compasses, a formulaic industrial repetition. Its stability depends on constant propping up by the buttresses: it is a defective body held up on crutches. ... The proof that Gothic works are of deficient plasticity is that they produce their greatest emotional effect when they are mutilated, covered in ivy and lit by the moon.[86]

After these initial influences, Gaudí moved towards Modernisme, then in its heyday. Modernisme in its earlier stages was inspired by historic architecture. Its practitioners saw its return to the past as a response to the industrial forms imposed by the Industrial Revolution's technological advances. The use of these older styles represented a moral regeneration that allowed the bourgeoisie to identify with values they regarded as their cultural roots. The Renaixença (rebirth), the revival of Catalan culture that began in the second half of the 19th century, brought more Gothic forms into the Catalan "national" style that aimed to combine nationalism and cosmopolitanism while at the same time integrating into the European modernizing movement.[87]

Some essential features of Modernisme were: an anticlassical language inherited from Romanticism with a tendency to lyricism and subjectivity; the determined connection of architecture with the applied arts and artistic work that produced an overtly ornamental style; the use of new materials from which emerged a mixed constructional language, rich in contrasts, that sought a plastic effect for the whole; a strong sense of optimism and faith in progress that produced an emphatic art that reflected the atmosphere of prosperity of the time, above all of the esthetic of the bourgeoisie.[88]

Quest for a new architectural language

Gaudí is usually considered the great master of Catalan Modernism, but his works go beyond any one style or classification. They are imaginative works that find their main inspiration in geometry and nature forms. Gaudí studied organic and anarchic geometric forms of nature thoroughly, searching for a way to give expression to these forms in architecture. Some of his greatest inspirations came from visits to the mountain of Montserrat, the caves of Mallorca, the saltpetre caves in Collbató, the crag of Fra Guerau in the Prades Mountains behind Reus, the Pareis mountain in the north of Mallorca and Sant Miquel del Fai in Bigues i Riells.[89]

Geometrical forms

This study of nature translated into his use of ruled geometrical forms such as the hyperbolic paraboloid, the hyperboloid, the helicoid and the cone, which reflect the forms Gaudí found in nature.[90] Ruled surfaces are forms generated by a straight line known as the generatrix, as it moves over one or several lines known as directrices. Gaudí found abundant examples of them in nature, for instance in rushes, reeds and bones; he used to say that there is no better structure than the trunk of a tree or a human skeleton. These forms are at the same time functional and aesthetic, and Gaudí discovered how to adapt the language of nature to the structural forms of architecture. He used to equate the helicoid form to movement and the hyperboloid to light. Concerning ruled surfaces, he said:

Paraboloids, hyperboloids and helicoids, constantly varying the incidence of the light, are rich in matrices themselves, which make ornamentation and even modelling unnecessary.[91]

Another element widely used by Gaudí was the catenary arch. He had studied geometry thoroughly when he was young, studying numerous articles about engineering, a field that praised the virtues of the catenary curve as a mechanical element, one which at that time, however, was used only in the construction of suspension bridges. Gaudí was the first to use this element in common architecture. Catenary arches in works like the Casa Milà, the Teresian College, the crypt of the Colònia Güell and the Sagrada Família allowed Gaudí to add an element of great strength to his structures, given that the catenary distributes the weight it regularly carries evenly, being affected only by self-canceling tangential forces.[92]

Gaudí evolved from plane to spatial geometry, to ruled geometry. These constructional forms are highly suited to the use of cheap materials such as brick. Gaudí frequently used brick laid with mortar in successive layers, as in the traditional Catalan vault, using the brick laid flat instead of on its side.[93] This quest for new structural solutions culminated between 1910 and 1920, when he exploited his research and experience in his masterpiece, the Sagrada Família. Gaudí conceived the interior of the church as if it were a forest, with a set of tree-like columns divided into various branches to support a structure of intertwined hyperboloid vaults. He inclined the columns so they could better resist the perpendicular pressure on their section. He also gave them a double-turn helicoidal shape (right turn and left turn), as in the branches and trunks of trees. This created a structure that is now known as fractal.[94] Together with a modulation of the space that divides it into small, independent and self-supporting modules, it creates a structure that perfectly supports the mechanical traction forces without need for buttresses, as required by the neo-Gothic style.[95] Gaudí thus achieved a rational, structured and perfectly logical solution, creating at the same time a new architectural style that was original, simple, practical and aesthetic.

Surpassing the Gothic

This new constructional technique allowed Gaudí to achieve his greatest architectural goal; to perfect and go beyond Gothic style. The hyperboloid vaults have their center where Gothic vaults had their keystone, and the hyperboloid allows for a hole in this space to let natural light in. In the intersection between vaults, where Gothic vaults have ribs, the hyperboloid allows for holes as well, which Gaudí employed to give the impression of a starry sky.[96]

Gaudí complemented this organic vision of architecture with a unique spatial vision that allowed him to conceive his designs in three dimensions, unlike the flat design of traditional architecture. He used to say that he had acquired this spatial sense as a boy by looking at the drawings his father made of the boilers and stills he produced.[97] Because of this spatial conception, Gaudí always preferred to work with casts and scale models or even improvise on-site as a work progressed. Reluctant to draw plans, only on rare occasions did he sketch his works—in fact, only when required by authorities.

Another of Gaudí's innovations in the technical realm was the use of a scale model to calculate structures: for the church of the Colònia Güell, he built a 1:10 scale model with a height of 4 metres (13 ft) in a shed next to the building. There, he set up a model that had strings with small bags full of birdshot hanging from them. On a drawing board that was attached to the ceiling he drew the floor of the church, and he hung the strings (for the catenaries) with the birdshot (for the weight) from the supporting points of the building—columns, intersection of walls. These weights produced a catenary curve in both the arches and vaults. At that point, he took a picture that, when inverted, showed the structure for columns and arches that Gaudí was looking for. Gaudí then painted over these photographs with gouache or pastel. The outline of the church defined, he recorded every single detail of the building: architectural, stylistic and decorative.[98]

Gaudí's position in the history of architecture is that of a creative genius who, inspired by nature, developed a style of his own that attained technical perfection as well as aesthetic value, and bore the mark of his character. Gaudí's structural innovations were to an extent the result of his journey through various styles, from Doric to Baroque via Gothic, his main inspiration. It could be said that these styles culminated in his work, which reinterpreted and perfected them. Gaudí passed through the historicism and eclecticism of his generation without connecting with other architectural movements of the 20th century that, with their rationalist postulates, derived from the Bauhaus school, and represented an antithetical evolution to that initiated by Gaudí, given that it later reflected the disdain and the initial lack of comprehension of the work of the modernista architect.

Among other factors that led to the initial neglect of the Catalan architect's work was that despite having numerous assistants and helpers, Gaudí created no school of his own and never taught, nor did he leave written documents. Some of his subordinates adopted his innovations, above all Francesc Berenguer and Josep Maria Jujol; others, like Cèsar Martinell, Francesc Folguera and Josep Francesc Ràfols graduated towards Noucentisme, leaving the master's trail.[99] Despite this, a degree of influence can be discerned in some architects that either formed part of the Modernista movement or departed from it and who had had no direct contact with him, such as Josep Maria Pericas (Casa Alòs, Ripoll), Bernardí Martorell (Olius cemetery) and Lluís Muncunill (Masia Freixa, Terrassa). Nonetheless, Gaudí left a deep mark on 20th-century architecture: masters like Le Corbusier declared themselves admirers, and the works of other architects like Pier Luigi Nervi, Friedensreich Hundertwasser, Oscar Niemeyer, Félix Candela, Eduardo Torroja and Santiago Calatrava were inspired by Gaudí. Frei Otto used Gaudí's forms in the construction of the Munich Olympic Stadium. In Japan, the work of Kenji Imai bears evidence of Gaudí's influence, as can be seen in the Memorial for the Twenty-six Martyrs of Japan in Nagasaki (Japanese National Architecture Award in 1962), where the use of Gaudí's famous "trencadís" stands out.[100]

Design and craftsmanship

During his student days, Gaudí attended craft workshops, such as those taught by Eudald Puntí, Llorenç Matamala and Joan Oñós, where he learned the basic aspects of techniques relating to architecture, including sculpture, carpentry, wrought ironwork, stained glass, ceramics, plaster modelling, etc.[101] He also absorbed new technological developments, integrating into his technique the use of iron and reinforced concrete in construction. Gaudí took a broad view of architecture as a multifunctional design, in which every single detail in an arrangement has to be harmoniously made and well-proportioned. This knowledge allowed him to design architectural projects, including all the elements of his works, from furnishings to illumination to wrought ironwork.

Gaudí was also an innovator in the realm of craftsmanship, conceiving new technical and decorative solutions with his materials, for example his way of designing ceramic mosaics made of waste pieces ("trencadís") in original and imaginative combinations. For the restoration of Mallorca Cathedral he invented a new technique to produce stained glass, which consisted of juxtaposing three glass panes of primary colours, and sometimes a neutral one, varying the thickness of the glass in order to graduate the light's intensity.[102]

.jpg.webp)

This was how he personally designed many of the Sagrada Família's sculptures. He would thoroughly study the anatomy of the figure, concentrating on gestures. For this purpose, he studied the human skeleton and sometimes used dummies made of wire to test the appropriate posture of the figure he was about to sculpt. In a second step, he photographed his models, using a mirror system that provided multiple perspectives. He then made plaster casts of the figures, both of people and animals (on one occasion he made a donkey stand up so it would not move). He modified the proportions of these casts to obtain the figure's desired appearance, depending on its place in the church (the higher up, the bigger it would be). Eventually, he sculpted the figures in stone.[103]

Urban spaces and landscaping

Gaudí also practiced landscaping, often in urban settings. He aimed to place his works in the most appropriate natural and architectural surroundings by studying the location of his constructions thoroughly and trying to naturally integrate them into those surroundings. For this purpose, he often used the material that was most common in the nearby environment, such as the slate of Bellesguard and the grey Bierzo granite in the Episcopal Palace, Astorga. Many of his projects were gardens, such as the Güell Park and the Can Artigas Gardens, or incorporated gardens, as in the Casa Vicens or the Güell Pavilions. Gaudí's harmonious approach to landscaping is exemplified at the First Mystery of the Glory of the Rosary at Montserrat, where the architectural framework is nature itself—here the Montserrat rock—nature encircles the group of sculptures that adorned the path to the Holy Cave.

Interiors

Equally, Gaudí stood out as interior decorator, decorating most of his buildings personally, from the furnishings to the smallest details. In each case he knew how to apply stylistic particularities, personalising the decoration according to the owner's taste, the predominant style of the arrangement or its place in the surroundings—whether urban or natural, secular or religious. Many of his works were related to liturgical furnishing. From the design of a desk for his office at the beginning of his career to the furnishings designed for the Sobrellano Palace of Comillas, he designed all furnishing of the Vicens, Calvet, Batlló and Milà houses, of the Güell Palace and the Bellesguard Tower, and the liturgical furnishing of the Sagrada Família. It is noteworthy that Gaudí studied some ergonomy in order to adapt his furnishings to human anatomy. Many of his furnishings are exhibited at Gaudí House Museum.[104]

Another aspect is the intelligent distribution of space, always with the aim of creating a comfortable, intimate, interior atmosphere. For this purpose, Gaudí would divide the space into sections, adapted to their specific use, by means of low walls, dropped ceilings, sliding doors and wall closets. Apart from taking care of every detail of all structural and ornamental elements, he made sure his constructions had good lighting and ventilation. For this purpose, he studied each project's orientation with respect to the cardinal points, as well as the local climate and its place in its surroundings. At that time, there was an increasing demand for more domestic comfort, with piped water and gas and the use of electric light, all of which Gaudí expertly incorporated. For the Sagrada Família, for example, he carried out thorough studies on acoustics and illumination, in order to optimise them. With regard to light, he stated:

Light achieves maximum harmony at an inclination of 45°, since it resides on objects in a way that is neither horizontal nor vertical. This can be considered medium light, and it offers the most perfect vision of objects and their most exquisite nuances. It is the Mediterranean light.[105]

Lighting also served Gaudí for the organisation of space, which required a careful study of the gradient of light intensity to adequately adapt to each specific environment. He achieved this with different elements such as skylights, windows, shutters and blinds; a notable case is the gradation of colour used in the atrium of the Casa Batlló to achieve uniform distribution of light throughout the interior. He also tended to build south-facing houses to maximise sunlight.[106]

Works

Gaudí's work is normally classed as modernista, and it belongs to this movement because of its eagerness to renovate without breaking with tradition, its quest for modernity, the ornamental sense applied to works, and the multidisciplinary character of its undertakings, where craftsmanship plays a central role. To this, Gaudí adds a dose of the baroque, adopts technical advances and continues to use traditional architectural language. Together with his inspiration from nature and the original touch of his works, this amalgam gives his works their personal and unique character in the history of architecture.

Chronologically, it is difficult to establish guidelines that illustrate the evolution of Gaudí's style faithfully. Although he moved on from his initially historicist approach to immerse himself completely in the modernista movement which arose so vigorously in the last third of the 19th century in Catalonia, before finally attaining his personal, organic style, this process did not consist of clearly defined stages with obvious boundaries: rather, at every stage there are reflections of all the earlier ones, as he gradually assimilated and surpassed them. Among the best descriptions of Gaudí's work was made by his disciple and biographer Joan Bergós, according to plastic and structural criteria. Bergós establishes five periods in Gaudí's productions: preliminary period, mudéjar-morisco (Moorish/mudéjar art), emulated Gothic, naturalist and expressionist, and organic synthesis.[107]

Early works

Gaudí's first works both from his student days and the time just after his graduation stand out for the precision of their details, the use of geometry and the prevalence of mechanical considerations in the structural calculations.[108]

University years

During his studies, Gaudí designed various projects, among which the following stand out: a cemetery gate (1875), a Spanish pavilion for the Philadelphia World Fair of 1876, a quay-side building (1876), a courtyard for the Diputació de Barcelona (1876), a monumental fountain for the Plaça Catalunya in Barcelona (1877) and a university assembly hall (1877).[109]

| Student works | |||

|---|---|---|---|

.jpg.webp) |

|

|

|

| Cemetery gate (1875) | Quay-side building (1876) | Fountain in Plaça Catalunya (1877) | University assembly hall (1877) |

Gaudí started his professional career while still at university. To pay for his studies, he worked as a draughtsman for some of the most outstanding Barcelona architects of the time, such as Joan Martorell, Josep Fontserè, Francisco de Paula del Villar y Lozano, Leandre Serrallach and Emili Sala Cortés.[110] Gaudí had a long-standing relationship with Josep Fontserè, since his family was also from Riudoms and they had known each other for some time. Despite not having an architecture degree, Fontserè received the commission from the city council for the Parc de la Ciutadella development, carried out between 1873 and 1882. For this project, Gaudí was in charge of the design of the Park's entrance gate, the bandstand's balustrade and the water project for the monumental fountain, where he designed an artificial cave that showed his liking for nature and the organic touch he would give his architecture.[111]

Gaudí worked for Francisco de Paula del Villar on the apse of the Montserrat monastery, designing the niche for the image of the Black Virgin of Montserrat in 1876. He would later substitute Villar in the works of the Sagrada Família. With Leandre Serrallach, he worked on a tram line project to Villa Arcadia in Montjuïc. Eventually, he collaborated with Joan Martorell on the Jesuit church on Carrer Casp and the Salesian convent in Passeig de Sant Joan, as well as the Villaricos church (Almería). He also carried out a project for Martorell for the competition for a new façade for Barcelona cathedral, which was never accepted. His relationship with Martorell, whom he always considered one of his main and most influential masters, brought him unexpected luck; he later recommended Gaudí for the Sagrada Família.

Early post-graduation projects

After his graduation as an architect in 1878, Gaudí's first work was a set of lampposts for the Plaça Reial, the project for the Girossi newsstands and the Mataró cooperative, which was his first important work. He received the request from the city council of Barcelona in February 1878, when he had graduated but not yet received his degree, which was sent from Madrid on 15 March of the same year.[112] For this commission he designed two types of lampposts: one with six arms, of which two were installed in the Plaça Reial, and another with three, of which two were installed in the Pla del Palau, opposite the Civil Government. The lampposts were inaugurated during the Mercè festivities in 1879. Made of cast iron with a marble base, they have a decoration in which the caduceus of Mercury is prominent, symbol of commerce and emblem of Barcelona.

| Early post-graduate works | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Lampposts | Girossi newsstands | Esteban Comella display | Gibert Pharmacy |

The Girossi newsstands project, which was never carried out, was a commission from the tradesman Enrique Girossi de Sanctis. It would have consisted of 20 newsstands, spread throughout Barcelona. Each would have included a public lavatory, a flower stand and glass panels for advertisements as well as a clock, a calendar, a barometer and a thermometer. Gaudí conceived a structure with iron pillars and marble and glass slabs, crowned by a large iron and glass roof, with a gas illumination system.[113]

The Cooperativa Obrera Mataronense (Mataró Workers' Cooperative) was Gaudí's first big project, on which he worked from 1878 to 1882, for Salvador Pagès i Anglada. The project, for the cooperative's head office in Mataró, comprised a factory, a worker's housing estate, a social centre and a services building, though only the factory and the services building were completed. In the factory roof Gaudí used the catenary arch for the first time, with a bolt assembly system devised by Philibert de l'Orme.[114] He also used ceramic tile decoration for the first time in the services building. Gaudí laid out the site taking account of solar orientation, another signature of his works, and included landscaped areas. He even designed the Cooperative's banner, with the figure of a bee, symbol of industriousness.

In May 1878 Gaudí designed a display cabinet for the Esteban Comella glove factory, which was exhibited in the Spanish pavilion at the Paris World Exhibition that year.[115] It was this work that attracted the attention of the entrepreneur Eusebi Güell, visiting the French capital; he was so impressed that he wanted to meet Gaudí on his return, beginning a long friendship and professional collaboration. Güell became Gaudí's main patron and sponsor of many of his large projects.

First Güell projects

Güell's first task for Gaudí, that same year, was the design of the furniture for the pantheon chapel of the Palacio de Sobrellano in Comillas, which was then being constructed by Joan Martorell, Gaudí's teacher, at the request of the Marquis of Comillas, Güell's father in law. Gaudí designed a chair, a bench and a prayer stool: the chair was upholstered with velvet, finished with two eagles and the Marquis's coat of arms; the bench stands out with the motif of a dragon, designed by Llorenç Matamala; the prayer stool is decorated with plants.

Also in 1878 he drew up the plans for a theatre in the former town of Sant Gervasi de Cassoles (now a district of Barcelona); Gaudí did not take part in the construction of the theatre, which no longer exists. The following year he designed the furniture and counter for the Gibert Pharmacy, with marquetry of Arab influence. The same year he made five drawings for a procession in honour of the poet Francesc Vicent Garcia i Torres in Vallfogona de Riucorb, where this celebrated 17th-century writer and friend of Lope de Vega was the parish priest. Gaudí's project was centred on the poet and on several aspects of agricultural work, such as reaping and harvesting grapes and olives; however, as a result of organisational problems Gaudí's ideas were not carried out.[116]

Between 1879 and 1881 he drew up a proposal for the decoration of the church of Sant Pacià, belonging to the Colegio de Jesús-María in Sant Andreu del Palomar: he created the altar in a Gothic style, the monstrance with Byzantine influence, the mosaics and the lighting, as well as the school's furniture. The church caught fire during the Tragic Week of 1909, and now only the mosaics remain, of "opus tesselatum", probably the work of the Italian mosaicist Luigi Pellerin.[117] He was given the task of decorating the church of the Colegio de Jesús-María in Tarragona (1880–1882): he created the altar in white Italian marble, and its front part, or antependium, with four columns bearing medallions of polychrome alabaster, with figures of angels; the ostensory with gilt wood, the work of Eudald Puntí, decorated with rosaries, angels, tetramorph symbols and the dove of the Holy Ghost; and the choir stalls, which were destroyed in 1936.[118]

In 1880 he designed an electric lighting project for Barcelona's Muralla de Mar, or seawall, which was not carried out. It consisted of eight large iron streetlamps, profusely decorated with plant motifs, friezes, shields and names of battles and Catalan admirals. The same year he participated in the competition for the construction of the San Sebastián social centre (now town hall), won by Luis Aladrén Mendivi and Adolfo Morales de los Ríos; Gaudí submitted a project that synthesised several of his earlier studies, such as the fountain for the Plaça Catalunya and the courtyard of the Provincial Council.[119]

Collaboration with Martorell

.jpg.webp)

A new task of the Güell-López's for Comillas was the gazebo for Alfonso XII's visit to the Cantabrian town in 1881. Gaudí designed a small pavilion in the shape of a Hindu turban, covered in mosaics and decorated with an abundance of small bells which jingled constantly. It was subsequently moved into the Güell Pavilions.[120]

In 1882 he designed a Benedictine monastery and a church dedicated to the Holy Spirit in Villaricos (Cuevas de Vera, Almería) for his former teacher, Joan Martorell. It was of neo-Gothic design, similar to the Convent of the Salesians that Gaudí also planned with Martorell. Ultimately it was not carried out, and the project plans were destroyed in the looting of the Sagrada Família in 1936.[121] The same year he was tasked with constructing a hunting lodge and wine cellars at a country residence known as La Cuadra, in Garraf (Sitges), property of baron Eusebi Güell. Ultimately the wine cellars, but not the lodge, were built some years later. With Martorell he also collaborated on three other projects: the church of the Jesuit School in Carrer Caspe; the Convent of the Salesians in Passeig de Sant Joan, a neo-Gothic project with an altar in the centre of the crossing; and the façade project for Barcelona cathedral, for the competition convened by the cathedral chapter in 1882, ultimately won by Josep Oriol Mestres and August Font i Carreras.[122]

Gaudí's collaboration with Martorell was a determining factor in Gaudí's recommendation for the Sagrada Família. The church was the idea of Josep Maria Bocabella, founder of the Devotees of Saint Joseph Association, which acquired a complete block of Barcelona's Eixample district.[123] The project was originally entrusted to Francisco de Paula del Villar y Lozano, who planned the construction of a neo-Gothic church, on which work began in 1882. However, the following year Villar resigned due to disagreements with the construction board, and the task went to Gaudí, who completely redesigned the project, apart from the part of the crypt that had already been built.[124] Gaudí devoted the rest of his life to the construction of the church, which was to be the synthesis of all of his architectural discoveries.

Orientalist period

During these years Gaudí completed a series of works with a distinctly oriental flavour, inspired by the art of the Middle and Far East (India, Persia, Japan), as well as Islamic-Hispanic art, mainly Mudejar and Nazari. Gaudí used ceramic tile decoration abundantly, as well as Moorish arches, columns of exposed brick and pinnacles in the shape of pavilions or domes.[125]

Between 1883 and 1888 he constructed the Casa Vicens, commissioned by stockbroker Manuel Vicens i Montaner. It was constructed with four floors, with façades on three sides and an extensive garden, including a monumental brick fountain. The house was surrounded by a wall with iron gates, decorated with palmetto leaves, work of Llorenç Matamala. The walls of the house are of stone alternated with lines of tile, which imitate yellow flowers typical of this area; the house is topped with chimneys and turrets. In the interior the polychrome wooden roof beams stand out, adorned with floral themes of papier maché; the walls are decorated with vegetable motifs, as well as paintings by Josep Torrescasana; finally, the floor consists of Roman-style mosaics of "opus tesselatum". Among the most original rooms is the smoking room, notable the ceiling, decorated with Moorish honeycomb-work, reminiscent of the Generalife in the Alhambra in Granada.[126]

| Orientalist works | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

.jpg.webp) |

| Casa Vicens (1883–88) | El Capricho (1883–85) | Güell Pavilions (1884–87) | Palau Güell (1886–88) | Compañía Trasatlántica (1888) |

In the same year, 1883, Gaudí designed the Santísimo Sacramento chapel for the parish church of San Félix de Alella, as well as some topographical plans for the Can Rosell de la Llena country residence in Gelida. He also received a commission to build a small annex to the Palacio de Sobrellano, for the Baron of Comillas, in the Cantabrian town of the same name. Known as El Capricho, it was commissioned by Máximo Díaz de Quijano and constructed between 1883 and 1885. Cristòfor Cascante i Colom, Gaudí's fellow student, directed the construction. In an oriental style, it has an elongated shape, on three levels and a cylindrical tower in the shape of a Persian minaret, faced completely in ceramics. The entrance is set behind four columns supporting depressed arches, with capitals decorated with birds and leaves, similar to those that can be seen at the Casa Vicens. Notable are the main lounge, with its large sash window, and the smoking room with a ceiling consisting of a false Arab-style stucco vault.[127]

Gaudí carried out a second commission from Eusebi Güell between 1884 and 1887, the Güell Pavilions in Pedralbes, now on the outskirts of Barcelona. Güell had a country residence in Les Corts de Sarrià, consisting of two adjacent properties known as Can Feliu and Can Cuyàs de la Riera. The architect Joan Martorell had built a Caribbean-style mansion, which was demolished in 1919 to make way for the Royal Palace of Pedralbes. Gaudí undertook to refurbish the house and construct a wall and porter's lodge. He completed the stone wall with several entrances, the main entrance with an iron gate in the shape of a dragon, with symbology allusive to the myths of Hercules and the Garden of the Hesperides.[128] The buildings consist of a stable, covered longeing ring and porter's lodge: the stable has a rectangular base and catenary arches; the longeing ring has a square base with a hyperboloid dome; the porter's lodge consists of three small buildings, the central one being polygonal with a hyperbolic dome, and the other two smaller and cubic. All three are topped by ventilators in the shape of chimneys faced with ceramics. The walls are of exposed brick in various shades of reds and yellows; in certain sections prefabricated cement blocks are also used. The Pavilions are now the headquarters of the Real Cátedra Gaudí, of the Polytechnic University of Catalonia.

In 1885 Gaudí accepted a commission from Josep Maria Bocabella, promoter of the Sagrada Família, for an altar in the oratory of the Bocabella family, who had obtained permission from the Pope to have an altar in their home. The altar is made of varnished mahogany, with a slab of white marble in the centre for relics. It is decorated with plants and religious motifs, such as the Greek letters alpha and omega, symbol of the beginning and end, gospel phrases and images of Saint Francis of Paola, Saint Teresa of Avila and the Holy Family and closed with a curtain of crimson embroidery. It was made by the cabinet maker Frederic Labòria, who also collaborated with Gaudí on the Sagrada Família.[129]

Shortly after, Gaudí received an important new commission from Güell: the construction of his family house, in the Carrer Nou de la Rambla in Barcelona. The Palau Güell (1886–1888) continues the tradition of large Catalan urban mansions such as those in Carrer Montcada. Gaudí designed a monumental entrance with a magnificent parabolic arch above iron gates, decorated with the Catalan coat of arms and a helmet with a winged dragon, the work of Joan Oñós. A notable feature is the triple-height entrance hall; it is the core of the building, surrounded by the main rooms of the palace, and it is remarkable for its double dome, parabolic within and conical on the outside, a solution typical of Byzantine art. For the gallery on the street façade Gaudí used an original system of catenary arches and columns with hyperbolic capitals, a style he used only here.[130] He designed the interior of the palace with a sumptuous Mudejar-style decoration, where the wood and iron coffered ceilings stand out. The chimneys on the roof are a remarkable feature, faced in vividly coloured ceramic tiles, as is the tall spire in the form of a lantern tower, which is the external termination of the dome within, and is also faced with ceramic tiles and topped with an iron weather vane.[131]

On the occasion of the World Expo held in Barcelona in 1888, Gaudí constructed the pavilion for the Compañía Trasatlántica, property of the Marquis of Comillas, in the Maritime Section of the event. He created it in a Granadinian Nazari style, with horseshoe arches and stucco decoration; the building survived until the Passeig Marítim was opened up in 1960. In the wake of the event he received a commission from Barcelona Council to restore the Saló de Cent and the grand stairs in Barcelona City Hall, as well as a chair for the queen Maria Cristina; only the chair was made, and Mayor Francesc Rius i Taulet presented it to the Queen.[132]

Neo-Gothic period

During this period Gaudí was inspired above all by mediaeval Gothic art, but wanted to improve on its structural solutions. Neo-gothic was one of the most successful historicist styles at that time, above all as a result of the theoretical studies of Viollet-le-Duc.[133] Gaudí studied examples in Catalonia, the Balearic Islands and Roussillon in depth, as well as Leonese and Castillian buildings during his stays in León and Burgos, and became convinced that it was an imperfect style, leaving major structural issues only partly resolved. In his works he eliminated the need of buttresses through the use of ruled surfaces, and abolished crenellations and excessive openwork.[134]

| Neo-gothic works | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

| Teresian College | Episcopal Palace | Casa Botines | Bodegues Güell | Torre Bellesguard |

The first example was the Teresian College (Col·legi de les Teresianes) (1888–1889), in Barcelona's Carrer Ganduxer, commissioned by San Enrique de Ossó. Gaudí fulfilled the wish of the order that the building should be austere, in keeping with their vows of poverty. He designed a simple building, using bricks for the exterior and some brick elements for the interior. Wrought ironwork, one of Gaudí's favourite materials, appeared on the façades. The building is crowned by a row of merlons which suggest a castle, a possible reference to Saint Teresa's Interior Castle.[135] The corners have brick pinnacles topped by helicoidal columns and culminate in a four-armed cross, typical of Gaudí's works, and with ceramic shields bearing various symbols of the order. The interior includes a corridor which is famous for the series of catenary arches that it contains. These elegant arches are decorative and support the ceiling and the floor above. For Gaudí, the catenary arch was an ideal constructional element, capable of supporting great loads with slender masonry.[136]

Gaudí received his next commission from a clergyman who had been a boyhood friend in his native Reus. When he was appointed bishop of Astorga, Joan Baptista Grau i Vallespinós asked Gaudí to design a new episcopal palace for the city, as the previous building had caught fire. Constructed between 1889 and 1915, in a neo-Gothic style with four cylindrical towers, it was surrounded by a moat. The stone with which it was built (grey granite from the El Bierzo area) is in harmony with its surroundings, particularly with the cathedral in its immediate vicinity, as well as with the natural landscape, which in late 19th-century Astorga was more visible than today. The porch has three large flared arches, built of ashlar and separated by sloping buttresses. The structure is supported by columns with decorated capitals and by ribbed vaults on pointed arches, and topped with Mudejar-style merlons. Gaudí resigned from the project in 1893, at the death of Bishop Grau, due to disagreements with the Chapter, and it was finished in 1915 by Ricardo García Guereta. It currently houses a museum about the Way of Saint James, which passes through Astorga.[137]

Another of Gaudí's projects outside of Catalonia was the Casa de los Botines, in León (1891–1894), commissioned by Simón Fernández Fernández and Mariano Andrés Luna, textile merchants from León, who were recommended Gaudí by Eusebi Güell, with whom they did business. Gaudí's project was an impressive neo-Gothic style building, which bears his unmistakable modernista imprint. The building was used to accommodate offices and textile shops on the lower floors, as well as apartments on the upper floors. It was constructed with walls of solid limestone.[138] The building is flanked by four cylindrical turrets surmounted by slate spires, and surrounded by an area with an iron grille. The Gothic façade style, with its cusped arches, has a clock and a sculpture of Saint George and the Dragon, the work of Llorenç Matamala.[139] As of 2010 it was the headquarters of the Caja España.

In 1892 Gaudí was commissioned by Claudio López Bru, second Marquis of Comillas, with the Franciscana Catholic Missions for the city of Tangier, in Morocco (at the time a Spanish colony). The project included a church, hospital and school, and Gaudí conceived a quadrilobulate ground-plan floor structure, with catenary arches, parabolic towers, and hyperboloid windows. Gaudí deeply regretted the project's eventual demise, always keeping his design with him. In spite of this, the project influenced the works of the Sagrada Família, in particular the design of the towers, with their paraboloid shape like those of the Missions.[140]

.jpg.webp)

In 1895 he designed a funerary chapel for the Güell family at the abbey of Montserrat, but little is known about this work, which was never built. That year, construction finally began on the Bodegas Güell, the 1882 project for a hunting lodge and some wineries at La Cuadra de Garraf (Sitges), property of Eusebi Güell. Constructed between 1895 and 1897 under the direction of Francesc Berenguer, Gaudí's aide, the wineries have a triangular end façade, a very steep stone roof, a group of chimneys and two bridges that join them to an older building. It has three floors: the bottom one for a garage, an apartment and a chapel with catenary arches, with the altar in the centre. It was completed with a porter's lodge, notable for the iron gate in the shape of a fishing net.

In the township of Sant Gervasi de Cassoles (now a district of Barcelona), the widow of Jaume Figueras commissioned Gaudí to renovate the Torre Bellesguard (1900–1909), former summer palace of King Martin I the Humane.[141] Gaudí designed it in a neo-Gothic style, respecting the former building as much as possible, and tried as always to integrate the architecture into the natural surroundings. This influenced his choice of local slate for the construction. The building's ground-plan measures 15 x 15 meters, with the corners oriented to the four cardinal points. Constructed in stone and brick, it is taller than it is wide, with a spire topped with the four-armed cross, the Catalan flag and the royal crown. The house has a basement, ground floor, first floor and an attic, with a gable roof.[142]

Naturalist period

During this period Gaudí perfected his personal style, inspired by the organic shapes of nature, putting into practise a whole series of new structural solutions originating from his deep analysis of ruled geometry. To this he added a great creative freedom and an imaginative ornamental style. His works acquired a great structural richness, with shapes and volumes devoid of rational rigidity or any classic premise.[143]

1898–1900

Commissioned by the company Hijos de Pedro Mártir Calvet, Gaudí built the Casa Calvet (1898–1899), in Barcelona's Carrer Casp. The façade is built of Montjuïc stone, adorned with wrought iron balconies and topped with two pediments with wrought iron crosses. Another notable feature of the façade is the gallery on the main floor, decorated with plant and mythological motifs. For this project, Gaudí used a Baroque style, visible in the use of Solomonic columns, decoration with floral themes and the design of the terraced roof. In 1900, he won the award for the best building of the year from Barcelona City Council.[144]

A virtually unknown work by Gaudí is the Casa Clapés (1899–1900), at 125 Carrer Escorial, commissioned by the painter Aleix Clapés, who collaborated on occasion with Gaudí, such as in decorating the Palau Güell and the Casa Milà. It has a ground floor and three apartments, with stuccoed walls and cast-iron balconies. Due to its lack of decoration or original structural solutions its authorship was unknown until 1976, when the architect's signed plans by Gaudí were discovered.[145] In 1900, he renovated the house of Dr. Pere Santaló, at 32 Carrer Nou de la Rambla, a work of equally low importance. Santaló was a friend of Gaudí's, whom he accompanied during his stay in Puigcerdà in 1911. It was he who recommended him to do manual work for his rheumatism.[146]

| Naturalist works (1898–1900) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Casa Calvet | Finca Miralles | Park Güell | Rosary of Montserrat |

Also in 1900, he designed two banners: for the Orfeó Feliuà (of Sant Feliu de Codines), made of brass, leather, cork and silk, with ornamental motifs based on the martyrdom of San Félix (a millstone), music (a staff and clef) and the inscription "Orfeó Feliuà"; and Our Lady of Mercy of Reus, for the pilgrimage of the Reus residents of Barcelona, with an image of Isabel Besora, the shepherdess to whom the Virgin appeared in 1592, work of Aleix Clapés and, on the back, a rose and the Catalan flag. In the same year, for the shrine of Our Lady of Mercy in Reus, Gaudí outlined a project for the renovation of the church's main façade, which ultimately was not undertaken, as the board considered it too expensive. Gaudí took this rejection quite badly, leaving some bitterness towards Reus, possibly the source of his subsequent claim that Riudoms was his place of birth.[147] Between 1900 and 1902 Gaudí worked on the Casa Miralles, commissioned by the industrialist Hermenegild Miralles i Anglès; Gaudí designed only the wall near the gateway, of undulating masonry, with an iron gate topped with the four-armed cross. Subsequently, the house for Señor Miralles was designed by Domènec Sugrañes, associate architect of Gaudí.

Gaudí's main new project at the beginning of the 20th century was the Park Güell (1900–1914), commissioned by Eusebi Güell. It was intended to be a residential estate in the style of an English garden city. The project was unsuccessful: of the 60 plots into which the site was divided only one was sold. Despite this, the park entrances and service areas were built, displaying Gaudí's genius and putting into practice many of his innovative structural solutions. The Park Güell is situated in Barcelona's Càrmel district, a rugged area, with steep slopes that Gaudí negotiated with a system of viaducts integrated into the terrain. The main entrance to the park has a building on each side, intended as a porter's lodge and an office, and the site is surrounded by a stone and glazed-ceramic wall. These entrance buildings are an example of Gaudí at the height of his powers, with Catalan vaults that form a parabolic hyperboloid.[148] After passing through the gate, steps lead to higher levels, decorated with sculpted fountains, notably the dragon fountain, which has become a symbol of the park and one of Gaudí's most recognised emblems. These steps lead to the Hypostyle Hall, which was to have been the residents' market, constructed with large Doric columns. Above this chamber is a large plaza in the form of a Greek theatre, with the famous undulating bench covered in broken ceramics ("trencadís"), the work of Josep Maria Jujol.[149] The park's show home, the work of Francesc Berenguer, was Gaudí's residence from 1906 to 1926, and currently houses the Casa-Museu Gaudí.

During this period Gaudí contributed to a group project, the Rosary of Montserrat (1900–1916). Located on the way to the Holy Cave of Montserrat, it was a series of groups of sculptures that evoked the mysteries of the Virgin, who tells the rosary. This project involved the best architects and sculptors of the era, and is a curious example of Catalan Modernism. Gaudí designed the First Mystery of Glory, which represents the Holy Sepulcher. The series include a statue of Christ Risen, the work of Josep Llimona, and the Three Marys sculpted by Dionís Renart. Another monumental project designed by Gaudí for Montserrat was never carried out: it would have included crowning the summit of El Cavall Bernat (one of the mountain peaks) with a viewpoint in the shape of a royal crown, incorporating a 20 metres (66 ft) high Catalan coat of arms into the wall.[150]

1901–1903

In 1901 Gaudí decorated the house of Isabel Güell López, Marchioness of Castelldosrius, and daughter of Eusebi Güell. Situated at 19 Carrer Junta de Comerç, the house had been built in 1885 and renovated between 1901 and 1904; it was destroyed by a bomb during the Civil War.[151] The following year Gaudí took part in the decoration of the Bar Torino, property of Flaminio Mezzalana, located at 18 Passeig de Gràcia; Gaudí designed the ornamentation of el Salón Árabe of that establishment, made with varnished Arabian-style cardboard tiles (which no longer exist).

A project of great interest to Gaudí was the restoration of the Cathedral of Santa Maria in Palma de Mallorca (1903–1914), commissioned by the city's bishop, Pere Campins i Barceló. Gaudí planned a series of works including removing the baroque altarpiece, revealing the bishop's throne, moving the choir-stalls from the centre of the nave and placing them in the presbytery, clearing the way through chapel of the Holy Trinity, placing new pulpits, fitting the cathedral with electrical lighting, uncovering the Gothic windows of the Royal Chapel and filling them with stained glass, placing a large canopy above the main altar and completing the decoration with paintings. This was coordinated by Joan Rubió i Bellver, Gaudí's assistant. Josep Maria Jujol and the painters Joaquín Torres García, Iu Pascual and Jaume Llongueras were also involved. Gaudí abandoned the project in 1914 due to disagreements with the Cathedral chapter.[152]

1904

Among Gaudí's largest and most striking works is the Casa Batlló (1904–1906). Commissioned by Josep Batlló i Casanovas to renovate an existing building erected in 1875 by Emili Sala Cortés,[153] Gaudí focused on the façade, the main floor, the patio and the roof, and built a fifth floor for the staff. For this project he was assisted by his aides Domènec Sugrañes, Joan Rubió and Josep Canaleta. The façade is of Montjuïc sandstone cut to create warped ruled surfaces; the columns are bone-shaped with vegetable decoration. Gaudí kept the rectangular shape of the old building's balconies—with iron railings in the shape of masks—giving the rest of the façade an ascending undulating form. He also faced the façade with ceramic fragments of various colours ("trencadís"), which Gaudí obtained from the waste material of the Pelegrí glass works. The interior courtyard is roofed by a skylight supported by an iron structure in the shape of a double T, which rests on a series of catenary aches. The helicoidal chimneys are a notable feature of the roof, topped with conical caps, covered in clear glass in the centre and ceramics at the top, and surmounted by clear glass balls filled with sand of different colours. The façade culminates in catenary vaults covered with two layers of brick and faced with glazed ceramic tiles in the form of scales (in shades of yellow, green and blue), which resemble a dragon's back; on the left side is a cylindrical turret with anagrams of Jesus, Mary and Joseph, and with Gaudí's four-armed cross.[154]

In 1904, commissioned by the painter Lluís Graner, he designed the decoration of the Sala Mercè, in the Rambla dels Estudis, one of the first cinemas in Barcelona; the theatre imitated a cave, inspired by the Coves del Drac (Dragon's Caves) in Mallorca. Also for Graner he designed a detached house in the Bonanova district of Barcelona, of which only the foundations and the main gate were built, with three openings: for people, vehicles and birds; the building would have had a structure similar to the Casa Batlló or the porter's lodge of the Park Güell.[155]

B2.jpg.webp)

The same year he built a workshop, the Taller Badia, for Josep and Lluís Badia Miarnau, blacksmiths who worked for Gaudí on several of his works, such as the Batlló and Milà houses, the Park Güell and the Sagrada Família. Located at 278 Carrer Nàpols, it was a simple stone building. Around that time he also designed hexagonal hydraulic floor tiles for the Casa Batlló, they were eventually used instead for the Casa Milà; they were a green colour and were decorated with seaweed, shells and starfish. These tiles were subsequently chosen to pave Barcelona's Passeig de Gràcia.[156]

Also in 1904 he built the Chalet de Catllaràs, in La Pobla de Lillet, for the Asland cement factory, owned by Eusebi Güell. It has a simple structure though very original, in the shape of a pointed arch, with two semi-circular flights of stairs leading to the top two floors. This building fell into ruin when the cement works closed, and when it was eventually restored its appearance was radically altered, the ingenious original staircase being replaced with a simpler metal one. In the same area he created the Can Artigas Gardens between 1905 and 1907, in an area called Font de la Magnesia, commissioned by the textile merchant Joan Artigas i Alart; men who had worked the Park Güell were also involved on this project, similar to the famous park in Barcelona.[157]

1906

In 1906 he designed a bridge over the Torrent de Pomeret, between Sarrià and Sant Gervasi. This river flowed directly between two of Gaudí's works, Bellesguard and the Chalet Graner, and so he was asked to bridge the divide. Gaudí designed an interesting structure composed of juxtaposed triangles that would support the bridge's framework, following the style of the viaducts that he made for the Park Güell. It would have been built with cement, and would have had a length of 154 metres (505 ft) and a height of 15 metres (49 ft); the balustrade would have been covered with glazed tiles, with an inscription dedicated to Santa Eulàlia. The project was not approved by the Town Council of Sarrià.[158]

The same year Gaudí apparently took part in the construction of the Torre Damià Mateu, in Llinars del Vallès in collaboration with his disciple Francesc Berenguer, though the project's authorship is not clear or to what extent they each contributed to it. The style of the building evokes Gaudí's early work, such as the Casa Vicens or the Güell Pavilions; it had an entrance gate in the shape of a fishing net, currently installed in the Park Güell. The building was demolished in 1939.[159] Also in 1906 he designed a new banner, this time for the Guild of metalworkers and blacksmiths for the Corpus Christi procession of 1910, in Barcelona Cathedral. It was dark green in colour, with Barcelona's coat of arms in the upper left corner, and an image of Saint Eligius, patron of the guild, with typical tools of the trade. The banner was burned in July 1936.[160]

Another of Gaudí's major projects and among his most admired works is the Casa Milà, better known as La Pedrera (1906–1910), commissioned by Pere Milà i Camps. Gaudí designed the house around two large, curved courtyards, with a structure of stone, brick and cast-iron columns and steel beams. The façade is built of limestone from Vilafranca del Penedès, apart from the upper level, which is covered in white tiles, evoking a snowy mountain. It has a total of five floors, plus a loft made entirely of catenary arches, as well as two large interior courtyards, one circular and one oval. Notable features are the staircases to the roof, topped with the four-armed cross, and the chimneys, covered in ceramics and with shapes that suggest mediaeval helmets. The interior decoration was carried out by Josep Maria Jujol and the painters Iu Pascual, Xavier Nogués and Aleix Clapés. The façade was to have been completed with a stone, metal and glass sculpture with Our lady of the Rosary accompanied by the archangels Michael and Gabriel, 4m in height. A sketch was made by the sculptor Carles Mani, but due to the events of the Tragic Week in 1909 the project was abandoned.[161]

1907–1908