Arak (drink)

Arak or araq (Arabic: ﻋﺮﻕ) is a distilled Levantine spirit of the anise drinks family. It is translucent and unsweetened.

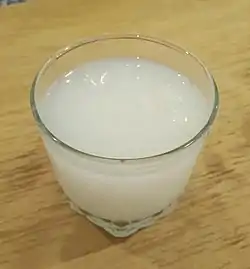

Arak with water and ice | |

| Type | Spirit |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | Levant |

| Region of origin | Near East |

| Alcohol by volume | 40–63% up to 95% if homemade moonshine |

| Proof (US) | 80–126 190 if homemade |

| Colour | transparent to translucent |

| Ingredients | Anise |

| Related products | Rakı, absinthe, ouzo, pastis, sambuca, aragh sagi |

History

Arak evolved from the Arab invention of alembic distillation in the 12th century.[1] As the vast majority of Arabs were Muslim at that time, the original usage of the distilled alcohol might have been for the production of perfumes and kohl, a cosmetic.[2] However, the distribution of arak and its derivatives – ranging from rakija in the Balkans to arrack in Indonesia and Malaysia – closely follows the pattern of the Arab-Islamic conquests, and in each of these locales the distilled alcohol is used as a beverage.

Traditional ingredients

Arak is traditionally made of only two ingredients, grapes and aniseed. Aniseeds are the seeds of the anise plant, and when crushed, their oil provides arak with a slight licorice taste.[3]

Etymology

The word arak comes from Arabic ʿaraq (عرق, meaning 'perspiration').[4]

Its pronunciation varies depending on local varieties of Arabic: [ʕaˈraʔ], [ʕaˈraɡ]. Arak is not to be confused with the similarly named liquor, arrack (which in some cases, such as in Indonesia—especially Bali—also goes by the name arak). Another similar-sounding word is aragh, which in Armenia, Iran, Azerbaijan and Georgia is the colloquial name of vodka, and not an aniseed-flavored drink. Rakı, mastika, and ouzo are aniseed-flavored alcoholic drinks, related to arak, popular in Turkey, North Macedonia, Bulgaria, Cyprus and Greece respectively.

Related products include rakı, absinthe, ouzo, pastis, sambuca, and aragh sagi.

Consumption

Arak is the traditional alcoholic beverage in Western Asia, especially in the Eastern Mediterranean[5][6] countries of Lebanon, Israel, Palestine, Syria, and Jordan.[1][7][2]

Arak is a stronger flavored liquor, and is usually mixed in proportions of approximately one part arak to two parts water in a traditional Eastern Mediterranean water vessel called an ibrik (Arabic: إبريق ibrīq). The mixture is then poured into ice-filled cups, usually small, but can also be consumed in regular sized cups. This dilution causes the clear liquor to turn a translucent milky-white color; this is because anethole, the essential oil of anise, is soluble in alcohol but not in water. This results in an emulsion whose fine droplets scatter the light and turn the liquid translucent, a phenomenon known as louching. Arak is commonly served with mezza, which may include dozens of small traditional dishes. In general, arak drinkers prefer to consume it this way, rather than alone. It is also consumed with raw meat dishes (e.g. kibbeh nayyeh in Lebanon and çiğ köfte in Turkey) or barbecues, along with dishes flavored with toum (garlic sauce).[8][9]

If ice is added to the drinking vessel before the water, the result is the formation of an aesthetically unpleasant layer on the surface of the drink, because the ice causes the oils to solidify. If water is added first, the ethanol causes the fat to emulsify, leading to the characteristic milky color. To avoid the precipitation of the anise (instead of an emulsion), drinkers prefer not to reuse a glass which has contained arak. In restaurants, when a bottle of arak is ordered, the waiter will usually bring a number of glasses for each drinker along with it for this reason.[10]

Preparation

Manufacturing begins with the vineyards, and quality grapevines are the key to making good arak.[11] The vines should be very mature and usually of a golden color. Instead of being irrigated, the vineyards are left to the care of the Mediterranean climate and make use of the natural rain and sun. The grapes, which are harvested in late September and October, are crushed and put in barrels together with the juice (in Arabic el romeli) and left to ferment for three weeks. Occasionally the whole mix is stirred to release the CO2.

Numerous types of stills exist, most usually made of stainless steel or copper. Pot and column stills are two types; which will affect the final taste and specificity of the arak. The authentic copper stills with a Moorish shape are the most sought after.[9]

The alcohol collected in the first distillation undergoes a second distillation, but this time it is mixed with aniseed. The ratio of alcohol to aniseed may vary and it is one of the major factors in the quality of the final product. The finished product is produced during a final distillation which takes place at the lowest possible temperature. For a quality arak, the finished spirit is then aged in clay amphoras to allow the angel's share to evaporate. The remaining liquid after this step is the most suitable for consumption.[6]

Moonshine

Arak made from various kinds of fruit based liqueurs as well as from wine is commonly produced as moonshine.

See also

- Araqi, a Sudanese drink

- Zivania, a Cypriot drink

References

- "Understanding Arak, an Ancient Spirit with Modern Appeal". Wine Enthusiast. 9 March 2020. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- "Drinking Arak - A Gourmet Ritual in the Middle East". Arab America. 3 January 2018. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- "The return of Arak". The New York Times. 25 January 2005. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- Dictionary definition: arak. (n.d.) American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fifth Edition. (2011). Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- "Arak – the Liquor of the Middle East". homebartendr.com. 22 January 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- "Arak: Liquid Fire". The Economist. December 2003. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- "The story of arak, a Lebanese drink infused with tradition |". AW. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- Sharif, Amani (20 February 2017). "A Brief History of Arak, Lebanon's National Drink". Culture Trip. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- Arak and Mezze: The Taste of Lebanon by Michael Karam

- "The Story of Arak in Lebanon". LibanonWeine. 25 May 2016. Archived from the original on 9 July 2020. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- "Another Anise Spirit Worth Knowing". The New York Times. August 2010.